Aspergilloma

- Article Author:

- Rebanta Chakraborty

- Article Editor:

- Krishna Baradhi

- Updated:

- 8/10/2020 9:26:26 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Aspergilloma CME

- PubMed Link:

- Aspergilloma

Introduction

Inert saprophytic colonization of preexisting cavitary spaces in pulmonary parenchyma, its presentation, as well as complications thereof, are referred to as aspergilloma. It falls within the broader class of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis.

A cavitary space with well-defined walls sequesters the fungal spores from both mechanical clearance, as well as immune eradication.

Description of cavitary aspergillus disease dates back to John Hughes Bennett in 1842, whose description of the soft tuberculous matter in multiple varied sized cavities in the lung closely resembles aspergillus disease. Deve in 1938 first formally described an aspergilloma and named it as “mega mycetoma.”[1] Subsequently, Hinson, and colleagues defined aspergilloma in its currently understood version of a saprophytic infection of preexisting lung cavities.[2]

Belcher and Plummer first formulated the classification of aspergilloma in 1960.[2]

If the surrounding lung parenchyma appeared normal and the cavity containing the aspergillus nidus was entirely lined by ciliated epithelium, it was termed as a simple aspergilloma.

On the other hand, a complex aspergilloma is one lined by extensively damaged surrounding lung parenchyma with epithelial distortion or destruction and fibrosis. Wall thickness of a complex aspergilloma is defined to be more than 0.3 cm.

Etiology

Aspergillus species are ubiquitous saprophytes in the environment. Pulmonary disease is caused mainly by the species Aspergillus fumigatus.

Risk factors for Aspergillus mediated lung disease, including aspergilloma, are:

- Pulmonary tuberculosis

- Cystic fibrosis

- Chronic bronchiectasis

- Pneumoconiosis

- Post infarct pulmonary cavity

- Post radiation pulmonary cavity

- Sarcoidosis

- Bronchial cysts and bullae

- Chronic lung abscess

- Lung malignancy

- Ankylosing spondylitis

CHRONIC DEBILITATING CONDITION (Impaired local bronchopulmonary defense)

- Malnutrition

- COPD

- Chronic liver disease

IMMUNOSUPRESSION

- Post-transplant

- Stem cell transplant

- Chemotherapy

- Neutropenia

- Prolonged corticosteroid use

- HIV

- Primary immunodeficiency syndromes

Epidemiology

The prevalence of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis varies, with a lower prevalence of less than 1 case per 100000 population in developed countries like the United States. The prevalence can be as high as 42.9 per 100000 in some African nations.

Aspergilloma incidence in patients with chronic pulmonary aspergillosis is about 25%. The estimated global 5-year period prevalence is 18/100000.[3] That translates to a global burden of 1.2 million patients with a higher reported incidence and prevalence in Africa, the western Pacific, and Southeast Asia.[3] Isolated aspergilloma without preexisting parenchymal disease is much rarer, reported at 0.13%. Interestingly even though invasive aspergillus disease is more common in patients with primary or acquired immunodeficiency, the incidence of aspergilloma is uncommon in HIV infected patients.[4]

Pathophysiology

Human lungs constantly have exposure to airborne fungus, which is a relatively ubiquitous component of our external environmental microbiome. Of all fungal organisms, aspergillus with species fumigatus and niger are common colonizers. The primary portal of entry for aspergillus spores is through the respiratory tract, although they can be commensals within the external auditory canal as well. In a diseased lung or with systemic immunodeficiency, these filamentous organisms then proliferate rapidly and become consequential.

Nearly 60% of aspergillomas thrive in a poorly drained and avascular cavitary space. Aspergillus, once harbored within cavitary airspace, adheres to the wall with its conidia, then germinates and, in the process, evokes an inflammatory reaction. The organism, along with the inflammatory debris, forms an amorphous mass identified as an aspergilloma. In very early stages, an ulceration or irregular cobblestoned cavity wall or floor may be the only pathological finding. Even with advanced disease, aspergilloma is most often mobile within the cavity, and thus change position with respect to the cavity in radiological images taken in different postures of the subject.

Hemoptysis is the most common clinical manifestation in symptomatic patients. The bleeding source is usually a bronchial vessel and can be secondary to:

- Direct invasion of capillaries of the wall lining

- Endotoxin release from the organism

- Mechanical irritation of exposed vessels within the cavity

- Rarely a rapidly growing cavity can erode into the pleural surface and intercostal arteries, causing massive, often fatal hemoptysis that is extremely challenging to control.

However, in an aggressively growing aspergilloma, chances of exposure and erosion into the much wider branched pulmonary arterial system is higher. Triggered by hypoxia, inflammation, and architectural distortion, there is an opening up of pulmonary arterial and bronchial arterial anastomotic plexus, which then become targets of erosion and hemoptysis. Inoue et al. did publish on increased expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in aspergilloma and the significance of monitoring their levels to predict massive hemoptysis.[5]

Multiple fungus balls are also seen, particularly in patients with chronic cystic bronchiectasis or multicystic or bullous disease.

In the brain, aspergillus involvement characteristically demonstrates the invasion of small, medium, and large vessels with the invasion of fungal hyphae through vascular walls into adjacent tissue. Initial hemorrhagic infarcts convert into septic infarcts, cerebritis, and abscess. When chronic, fibrosis, and granuloma formation follows. Although CNS involvement is mostly through hematogenous dissemination, local infiltration into the base of the skull can cause osteomyelitis or meningitis.

Histopathology

Aspergillus is a saprophytic filamentous fungus that thrives in a moist environment in soil, plants, and decaying vegetables. However, the conditions that favor dispersion of spores are dry and dusty surroundings, hay barns, compost sites, etc. Aspergillus fumigatus is the most prevalent human pathogen, although Aspergillus niger, A. flavus, and A. oxyzae are also reported to cause human disease.

The organism is characterized by 4 to 12 mm long septate hyphae with dichotomous branching, and with long conidiophores carrying numerous spores on their tips.

In a histologic specimen, aspergilloma appears as a soft mesh of inflamed, bloated, septate hyphae, fibrin, blood clots, cellular debris, and mucous residues. The central core is often necrotic. Although the lining of a simple aspergilloma could be ciliated epithelium, the epithelial lining is more often pseudostratified columnar or metaplastic squamous epithelium. Depending upon the severity of inflammation and the time course of progression, the walls can have evidence of chronic granulomatous inflammation, lymphoid follicles, endarteritis, and even ulceration and fibrosis.

History and Physical

There is a generalized understanding of predisposition among patients to specific forms of aspergillus mediated disease. Individuals with atopy or predisposition to hypersensitivity are more prone to have obstructive bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Immunocompromised patients more often are the ones to get invasive aspergillus infections, while mycetoma is more common in immunocompetent patients with preexisting lung disease. However, the overlap between these predisposition categories exist. Patients with mycetoma can develop a hypersensitivity response akin to allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA).[6] A chronic mycetoma that is unchanged over months to years can also suddenly metamorphose into a rapidly invasive pulmonary infection subject to immune status and general debilitation.

Depending upon host immune response, constitution, and the propensity of fungal invasion of parenchyma, clinical symptoms can be variable. A subset of patients may be asymptomatic with an incidental diagnosis of an aspergilloma.

However, hemoptysis is the most common clinical presentation reported anywhere between 54% to 87.5% in various case series.[7][8] It can turn into a massive fatal hemorrhage in 30% of patients. Interestingly, the size of mycetoma, the complexity of the lesion, the underlying predisposing lung disease, or prior minor hemoptysis cannot predict massive hemoptysis in aspergilloma.[9][10] Fever is rare, although constitutional symptoms of malaise, and weight loss may occur. If the organism invades the surrounding parenchyma, recurrent pneumonia, chronic cough, or pulmonary fibrosis can occur.[11] Reports also exist of disseminated infections involving a more considerable extent of parenchyma, airway, or even other organs.

EXTRAPULMONARY ASPERGILLOMA

While fungal endocarditis accounts for less than 2% of all causes of endocarditis, aspergillus accounts for 20 to 25% of all cases of fungal endocarditis. Invasive aspergillus disease involving heart valves and chambers are even rarer.[12][13][14]

There are case reports of aspergilloma of the heart almost uniquely in leukemia patients on chemotherapy or post stem cell transplant. They usually carry an ominous prognosis with death reported in all but one case within days to weeks of diagnosis. A transthoracic echocardiogram is a valuable diagnostic tool. Fungal vegetations on valves appear bulkier and more mobile and are prone to embolic complications, particularly to the brain. A combination of antifungal therapy with valve replacement is the recommended therapeutic approach. If a patient survives, lifelong antifungal treatment post-surgical valve replacement is advocated.

CNS ASPERGILLOMA

Translocation of organisms through the vascular channels of nasal sinuses or pulmonary vasculature leads to single or multiple cerebral abscess formation. Additionally, aspergillus also exhibits a tendency to invade the intima of arteries and veins, causing necrotizing arteritis, thrombosis, and hemorrhage. The anterior and middle cerebral arterial distributions are most commonly involved.

In CNS aspergilloma, the initial presentation is with focal neurological deficits affecting the circulation territory involved. With progression, patients may have features of meningitis or symptoms of raised intracranial pressure. Rarely intra-aortic thrombosis leads to mycotic aneurysms where clinical manifestations are similar to acute subarachnoid hemorrhage. Common presenting symptoms are acute or subacute headache, vomiting, hemiparesis, cranial nerve deficits, convulsions, and sensory impairment of varying degrees. Patients are often afebrile or have a low-grade fever, and the disease may have an indolent course over months.[15][16]

Evaluation

In a relevant clinical setting, characteristic CT chest findings combined with a microbial presence on sputum culture and serological evidence (serum antibodies) clinches the diagnosis.

The European Society for Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society, has published the most comprehensive guideline for diagnosis and management of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis, including aspergilloma. Consistent radiological findings, in association with serological and microbiological evidence of Aspergillus species in an individual, with symptoms lasting over three months satisfies the criteria for diagnosis after excluding other differentials with certainty.

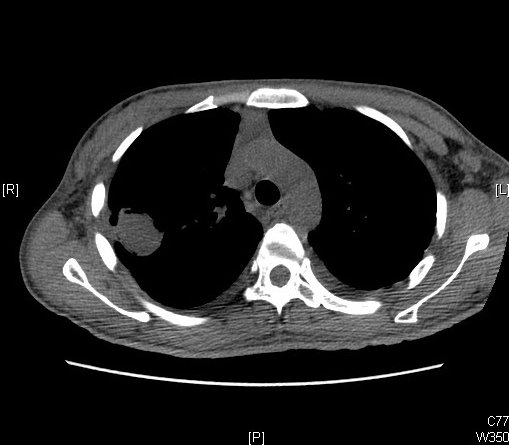

A chest X-ray is often the first diagnostic test ordered in a patient presenting with symptoms. It shows upper lobe predominant cavitation, thickening, scarring, and occasionally a rounded mass-like opacity within the cavity.

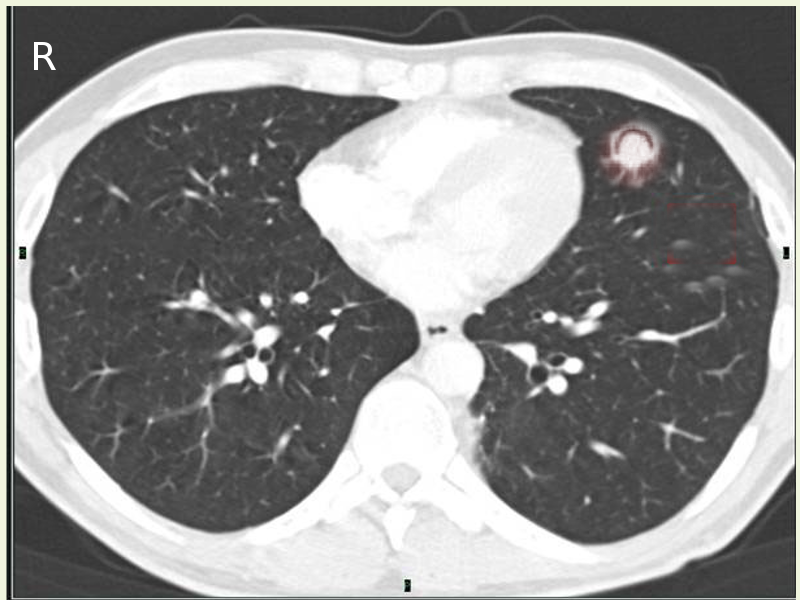

CT scan provides more delineation and has some characteristic findings

- The appearance of a solid spherical lesion within the cavitary space

- Halo sign of surrounding inflammatory reaction around the cavity wall

- Air crescent sign separating the fungus ball from the wall in the entirety or part of its circumference. (also present in lung abscess, hydatid cyst, and granulomatosis with polyangiitis)

- Monod sign characterized by a change in position of the ball concerning the cavity, with a change in the position of the patient during imaging.

CT helps in defining the cavity wall thickness, architectural distortion and inflammation of surrounding parenchyma and pleura, relationship of the mycetoma with surrounding blood vessels as well as nature of neovascularization both in lung parenchyma and parietal pleura.

The upper lobe of either lung is the most common location, although the superior segment of the lower lobe can also be involved. Denning et al. have prescribed evidence of endobronchial aspergilloma in HIV patients as has been corroborated by later case reports even in immunocompetent patients or in association with inhaled foreign bodies.

Once imaging is suggestive, evidence of microbial presence, as well as immune response, is the next approach in the algorithm. Assay against galactomannan antigen - a polysaccharide component of the cell wall has high specificity. Usually, the sensitivity of galactomannan antigen is higher in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid than serum, although both tests are available commercially. False-positive are seen in patients concurrently on piperacillin-tazobactam, while false negatives can be seen with high dose steroid therapy or with other non-fumigatus species of aspergillus.

IgG antibodies against Aspergillus species diagnosed by precipitin assay are positive in over 90% cases. Aspergillus specific IgE is also fairly elevated.

Confirmation of Aspergillus species in fungal stain, culture or polymerase chain reaction, adds weight to the diagnosis but are not diagnostic by themselves because of poor diagnostic yield and low sensitivity as well as specificity. An isolated sputum culture can be negative in over 50% of cases. Occasionally biopsy and video thoracoscopy can also clinch the diagnosis.

On radiological diagnosis of a solitary brain abscess, which is more than 1.5 cm, stereotactic aspiration of contents helps in diagnosis, relief of mass effect, and in improving the efficacy of antifungal therapy. Complete evacuation is, however, not recommended due to the risk of hemorrhage within the evacuated cavity.

CNS aspergilloma is also best confirmed by CT or MRI. Chronic abscess demonstrates ring and homogenous enhancement. Small cerebral abscesses not apparent on CT, can be picked up by increased sensitivity of MR imaging.

In general lumbar puncture is contraindicated due to the propensity of cerebral edema and, therefore, herniation and abscess rupture post puncture. Increased cellularity and CSF proteins with near-normal glucose levels are characteristic, although organisms are rarely found in CSF. The septate hyphae and conidia of Aspergillus species are best detected with Gomori Methenamine silver stain.

Immunoassay by double diffusion counter immunoelectrophoresis, immunofluorescence, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay can be helpful in diagnosis.

Treatment / Management

Even though aspergillomas can often be diagnosed incidentally in an asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic patient, there is a significant risk of evolving complications. The natural history and risk of complications, therefore, become a deciding factor in choosing between surgical and conservative treatment options. Rafferty and colleagues noted that 20% of non surgically treated mycetoma progresses to invasive aspergillosis. Similarly, Paneth et al. observed that after an episode of hemoptysis, 5-year survival for operated patients was 41% compared to 84% for conservatively treated patients. Treatment approach has, therefore, leaned towards surgical resection either preemptively on every patient diagnosed with aspergilloma, or in those with even one episode of hemoptysis, if the patient is a surgical candidate. Massard and colleagues advocated the prophylactic resection approach while Daly and colleagues preferred surgery only after hemoptysis.[17][18]

For patients with normal respiratory function, and with aspergilloma involving only one lung, 30-day postoperative mortality is anywhere between 1 to 5 %. Antifungal therapy alone is, on the other hand, of limited benefit in treating either simple or complex aspergilloma.[19][20]

A significant proportion of patients with aspergilloma have a preexisting diseased lung. Therefore resection with lung-sparing surgery has been gaining ground over the years. While wedge resection can occasionally be an option for a small, simple mycetoma, anatomical resection of segments or lobes has been the favored approach. Evaluation of pleural space is done carefully to ensure the absence of fistula or residual infection. But at the same time, manipulation of the mycetoma itself is reduced to a minimum.

Pneumonectomy, although less favored can be a necessity in the following circumstances

- Intraoperative injury to major vessels like pulmonary artery

- Second stage pneumonectomy for lobar torsion

- Multiple unilateral complex mycetoma

- Significantly destroyed surrounding lung tissue

- Megamycetoma

Endo and colleagues performed pneumonectomies in 35% of their reported patients without any postoperative mortality.[21]

Cavernostomy and cavernoplasty followed by muscle flap interposition was a practice in vogue until the late 1930s. It fell out of favor with increased morbidity and mortality compared to surgical resection. It has been slowly coming back in practice for a limited subgroup of patients who are not surgical candidates.[22][23]

For patients with pleural involvement with pleural aspergilloma, an open window thoracostomy or first stage thoracoplasty is performed, just as in chronic empyema. Certain centers will perform an intrathoracic muscle transposition in the same setting, thus obliterating the cavity.[24]

These surgical procedures do have complications like shoulder deformity, restriction of mobility, chronic postoperative pain, and scoliosis that should be addressed with patients before surgery.

Major surgical complications include massive hemorrhage, bronchopleural fistula, empyema, and rarely lobar torsion. Pleural complications involve residual infection, empyema, incomplete reexpansion, and prolonged air leaks. A preexisting underlying lung disease like tuberculosis, emphysema, or fibrosis leads to loss of elasticity of the affected lung, thus preventing reexpansion. The incidence of all complications has been reported to be as high as 60%.[25][26] Surgical mortality in complex mycetomas ranges from 0% to 44%.

A local pulmonary or pleural recurrence often leads to a dramatic deteriorating clinical course. Even prophylactic adjuvant antifungal pharmacotherapy does not seem to reduce the risk of this adverse effect.[27]

The source of postoperative bleeding can be aberrant systemic arteries, twisted bronchial vessels, or vascular adhesions due to chronic inflammation. Preoperative bronchial arterial embolization has been attempted in scenarios where there is a high risk of postoperative bleeding.[28]

Passera and colleagues address some of the challenges of the surgery itself.[8]

- Bronchovascular hilum can have induration with extra bronchial fibrosis and nodes affected by chronic infection. Routine taping of the main artery before dissection can help avoid bleeding complications.

- Extrapleural dissection reduces the risk of rupture of mycetoma in pleural space as well as the risk of bleeding.

- A bronchopleural fistula from bronchial deficiency can be an outcome of chronic inflammation, nonviable tissue, calcification, and atrophy. Coverage of the bronchial stump with pericardial, omental, or muscle flaps decreases the risk.

- Finally, the obliteration of residual pleural cavity reduces the risk of empyema or residual infection in the pleural space not adequately filled by entrapment of the remaining lobes.

For inoperable patients, intracavitary instillation of antifungal agents through percutaneous or intrabronchial catheters can lead to short term clinical improvement.[29][30]

Oakley and colleagues devised an algorithm for appropriate pre-surgical evaluation and risk stratification to improve outcomes. They divided patients into four categories

- CLASS 1 - fit individuals with no symptoms

- CLASS 2 - Fit individuals with severe symptoms

- CLASS 3 - Unfit individuals with no symptoms

- CLASS 4 - Unfit individuals with severe symptoms

Class 2 individuals were directed to surgical resection, while class 4 individuals were chosen for intracavitary installation or cavernostomy.

Surgical removal of aspergillus abscess, granuloma, and focally infarcted brain, coupled with systemic antifungal therapy, form the mainstay of management of CNS aspergillomas. When non-eloquent brain areas are involved, lobectomy for solitary Aspergillus fumigatus abscess is also an endorsed treatment option.

Some centers do prefer voriconazole extended therapy as an adjuvant treatment post-resection to control pleural contamination and encourage bronchial stump healing.[25]

Postoperative survival has been reported to be similar in both simple and complex aspergilloma.[31][32]

Amphotericin B is the mainstay among pharmacological agents in brain aspergilloma. Liposomal amphotericin B is significantly less toxic than free amphotericin B. However, because of the poor CSF penetration of systemic forms, intracatheter installation into the abscess cavity has also been an advocated approach. A combination of 5-fluorocytosine 50-150 mg/kg orally every six hours with rifampin can have a synergistic benefit with amphotericin.[33] The postoperative phase of patients with CNS aspergilloma demonstrates complications with remote intracerebral infarcts from the primary site of involvement. The use of steroids to control postoperative cerebral edema along with stress has been implicated as a cause of the dissemination of fungal hyphae to those remote vascular sites.[34][35]

BRONCHIAL ARTERIAL EMBOLIZATION FOR MASSIVE HEMOPTYSIS

Bronchial arterial embolization is the favored approach for patients with massive hemoptysis both as a first-line treatment as well as a bridge to more definitive surgical resection. However, in advanced disease, architectural distortion, neovascularization, and multiple vascular sources often make identification and control a challenging task.

Source of hemoptysis is the bronchial circulation in 90% cases, although various thoracic and abdominal branches of the aorta can provide collateral supplies to interstitium and bronchi rarely in 10% of cases. Identification and distinction from ectopic or orthotopic bronchial arteries can be challenging even on bronchial arteriograms. Bronchial arterial branches tend to follow a vertical or horizontal course before joining the bronchial tree, unlike non-bronchial collaterals who follow a transpleural course not following the bronchial tree.[36]

In 70% of instances, bronchial arteries arise from the descending thoracic aorta in the T5-T6 segment, with variants arising from the aortic arch or ascending aorta and occasionally from other aortic branches in thorax or abdomen. Importantly, in the same context, is the path of the anterior spinal artery receiving collaterals from up to eight segmental medullary arteries, ventral to lower thoracic and upper lumbar spinal cord.[37][38][39]

Apart from supplying pulmonary interstitium and bronchi, bronchial arteries also provide blood flow to visceral pleura, the middle third of the esophagus, vasa vasorum of the aorta and pulmonary artery, and mediastinum.

Complications and adverse events are therefore related to nontarget embolization and transient vascular disruption in other mediastinal structures. Transient chest pain and dysphagia are the commonest reported adverse events and are usually self-limiting.[40][41]

Anterior spinal arterial embolization causing acute transverse myelitis is the most devastating outcome. However, it has been increasingly rare with advanced angiographic technique, use of microcatheters, and hypo or iso-osmolar contrast agents. Its rate of occurrence over the years has been reported between 1.4 to 6.5%.[42][43] Unintentional embolization of the occipital cortex through a fistula between a bronchial artery and pulmonary vein or vertebral arterial branch has been rarely reported, thus leading to cortical blindness.

Since adverse effects are rare, technical success occurs in greater than 90% of interventions with clinical success reported at 73 to 99% immediately post embolization. Unfortunately, recurrence is also frequent at 10 to 55% in studies up to a 4-year follow up.[44][42][45]

Differential Diagnosis

Differentials of a space-occupying lesion within a lung cavity in imaging includes

- Primary lung malignancy

- Metastatic disease

- Aspergilloma

- Hydatid cyst

- Lung abscess.

Each one of them, therefore, merits consideration in the initial workup to diagnosis.

Prognosis

Spontaneous resolution of Aspergilloma occurs in <10% cases. However, progression to chronic cavitary pulmonary aspergillosis or chronic, necrotizing pulmonary aspergillosis and fibrosis are quite common, which necessitates continued observation even after initial therapy. A low dose CT chest every 6 to 12 months in immunocompetent patients is the diagnostic method of choice. The frequency is somewhat shorter in immunosuppressed. A new episode of hemoptysis always warrants immediate investigation with imaging. A rising Aspergillus IgG titer is indicative of treatment failure.

Complications

Hemoptysis is the most common presentation, as well as a complication of pulmonary aspergilloma. It can turn into a massive fatal hemorrhage in 30% of patients.

Chronic mycetoma can induce inflammation in surrounding parenchyma, thus developing a variable extent of pulmonary fibrosis.

Among extrapulmonary manifestations, CNS aspergilloma can be dreadful in its varied presentations as intracerebral abscess, meningitis, intra-aortic thrombosis, and mycotic aneurysm and even subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Cardiac aspergilloma, as reported so far, is also almost universally fatal.

Deterrence and Patient Education

In a high incidence geographical location, the burden of diseases like tuberculosis is also very high. A patient presenting with massive hemoptysis is therefore presumed often to have TB. Antimicrobial therapy frequently starts before microbial confirmation. In a resource-poor setting with challenging infrastructure, confirming an aspergillus disease diagnosis by bronchoscopy or serology, therefore, is often impossible. Even when diagnosed, individualizing care is complicated.

Most of these patients require long term follow up and multiple stage therapeutic intervention for the complexity of the underlying disease. We, therefore, ensure addressing roadblocks to compliance and adherence at the first interaction along with educating them on the available choice of treatment options, complications, and risk of inadequate treatment. Shared decision making in this process improves the patient's sense of responsibility and ownership in the treatment process.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Patients with aspergilloma or chronic pulmonary aspergillosis tend to have preexisting diseased lung with compromised function. Therefore surgical planning requires a thorough and interprofessional evaluation involving thoracic surgeon, pulmonary and infectious disease specialist, which is challenging in a resource-poor setting. In a center that does not handle patients with similar profiles regularly, immediate post-operative care, as well as long term surveillance and management of complications, are challenging. A diagnosis should prompt referral to tertiary care centers or high volume centers acquainted with the spectrum of aspergillus lung disease or metastatic disease.

Education and raising awareness among patients with preexisting cavitary lung disease, chronic immunosuppression, or chronic debilitating health condition like severe COPD, chronic liver disease, or malnutrition is therefore important. All individuals with the above risk factors and their family members must seek the attention of the nearest healthcare provider with any new-onset symptoms of hemoptysis or persistent chronic fever and cough. Similarly, any new neurological symptoms of confusion, headache, the focal neurological deficit with accompanying fever need urgent evaluation.

Irrespective of the final location of management, the initial identification still has to happen at a peripheral level from the primary care setting itself as an earlier intervention in a reasonably healthy patient augurs a better outcome. Knowledge of preexisting cavitary lung disease, immunosuppression, and generalized debilitation should prompt a thorough investigation of new symptoms of a nagging cough, and hemoptysis. Identification of new content within the cavity should prompt workup to rule out aspergillus infection as well as primary or metastatic malignancy. Once recognized as an aspergilloma, mere antifungal therapy is not sufficient as a treatment option, and due referral for surgical resection or intracavitary therapy should be a consideration.

Both the diagnostic and therapeutic approach to aspergillosis need to employ an interprofessional healthcare team approach. Primary care/family physicians need to be familiar enough with this condition to recognize it and seek the consult of a specialist. This would include an infectious disease specialist as well as a physician with a specialty in the affected organ system. Nursing staff with specialty training in infectious disease can assist with monitoring, assessing therapeutic effectiveness, as well as inpatient administration, and reporting any concerns they encounter. A board specialized infectious disease pharmacist can be an invaluable addition to the team, assisting with agent selection, performing medication reconciliation, and providing information on potential adverse drug reactions. When this type of interprofessional collaboration occurs, therapy can be optimized, and adverse events minimized, leading to better patient care and outcomes. [Level V]

(Click Image to Enlarge)