Burn Resuscitation And Management

- Article Author:

- Timothy Schaefer

- Article Editor:

- Omar Nunez Lopez

- Updated:

- 7/31/2020 3:19:44 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Burn Resuscitation And Management CME

- PubMed Link:

- Burn Resuscitation And Management

Introduction

Most burns are small and are treated at home or by local providers as outpatients. This chapter will focus on the initial resuscitation and management of severe burns. (Also see Burns, Evaluation and Management and Burns, Thermal).[1][2][3] Burn severity classification is determined by the patient's age, the percentage of total body surface area burned (%TBSA), depth of burn, type of burn and whether specific body parts are involved. Patients are classified as having severe burns if they have any of the following;

- >10% TBSA in children (<10 years old) or elderly (>50 years old)

- >20% TBSA in adults

- > 5% full thickness

- high-voltage electrical burns

- significant burns to the face, eyes, ears, joints or genitalia

Other factors that should be considered and will increase the patient’s morbidity and mortality include associated inhalation injury, associated traumatic injury and the patient’s baseline medical conditions like heart disease or lung disease.[4]

Severe burns cause not only significant injury at the local burn site but also a systemic response throughout the body. Inflammatory and vasoactive mediators such as histamines, prostaglandins, and cytokines are released causing a systemic capillary leak, intravascular fluid loss, and large fluid shifts. These responses occur mostly over the first 24 hours peaking at around six to eight hours after injury. This response, along with decreased cardiac output and increased vascular resistance, can lead to marked hypovolemia and hypoperfusion called “burn shock.” This can be managed with aggressive fluid resuscitation and close monitoring for adequate, but not excessive, IV fluids. [5][6]It is important to remember that burns by themselves do not cause significant hypotension initially and “burn shock” develops over the first few hours. If the patient is profoundly hypotensive initially, other causes of hypotension should be sought.

Anatomy and Physiology

Burns to the face, eyes, ears, joints, hands, or genitalia are genitalia are generally considered more significant and require transfer to a burn center.

Indications

Contraindications

Excessive fluids are contraindicated in the hemodynamically stable burn patient, as this likely contributes to edema.

Preparation

If a trauma with extensive burns is suspected, the team should prepare for burn resuscitation which includes fluids, sterile sheets, and having pain medications quickly available.

Technique

Resuscitation for Major Burns

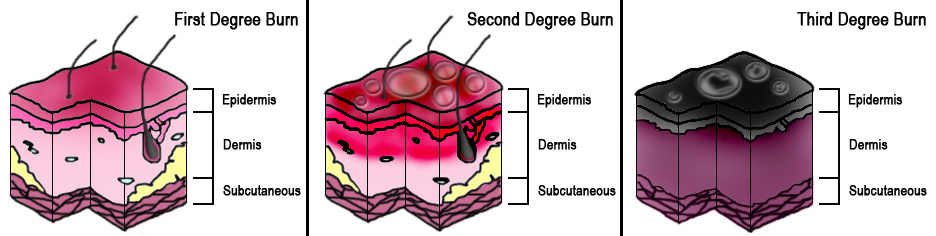

Burns are dramatic injuries that can draw healthcare provider’s attention away from more immediate life or limb-threatening problems. The initial assessment and management of severely burned patients should be similar to the approach of a major trauma patient. However, for the burn patient, the very first step is to immediately stop the burning process and remove burning or hot items from skin contact. Providers should obtain an initial A.M.P.L.E. history (allergies, medications, past medical history, last oral intake, events of injury). The primary survey assesses the A.B.C.s for life-threats. In the burn patient, attention should focus on the airway looking for oral burns that might cause swelling and obstruction, breathing problems from smoke inhalation or lung injury, and bleeding or circulation problems by looking for life-threatening bleeding and checking blood pressure, heart rate, and pulses. The next step would be resuscitation and immediate intervention for life-threats. This is followed by a secondary survey with a complete physical exam. Evaluating and treating the burns are part of the secondary survey. The key physical exam findings to record in burns are the extent of the burns, expressed as a percentage of total body surface area burned (% TBSA), and the depth of the burns, expressed as superficial (or first-degree), partial thickness (or second-degree) or full thickness (or third-degree).

Patients with burns of more than 20% - 25% of their body surface should be managed with aggressive IV fluid resuscitation to prevent “burn shock." A variety of formulas exist, like Brooke, Galveston, Rule of Ten, etc.4, but the most common formula is the Parkland Formula. This formula estimates the amount of fluid given in the first 24 hours, starting from the time of the burn.[10][11][12]

The Formula

Four mL lactated ringers solution × percentage total body surface area (%TBSA) burned × patient's weight in kilograms = total amount of fluid given in the first 24 hours.

- One-half of this fluid should be given in the first eight hours.

For example, a 75 kg patient with 55% total body surface area burn would need; 4 mL LR × 75kg × 55% TBSA = 16,500 mL in the first 24 hours, with 8,250 mL in the first eight hours or approximately 1 liter/hr for the first eight hours.

For pediatric patients, the Parkland Formula can be used plus the addition of normal maintenance fluids added to the total.

Whichever formula is used, the important point to remember is the fluid amount calculated is just a guideline. Patient’s vital signs, mental status, capillary refill and urine output must be monitored and fluid rates adjusted accordingly. Urine output of 0.5 mL/kg or about 30 – 50 mL/hr in adults and 0.5-1.0 mL/kg/hr in children less than 30kg is a good target for adequate fluid resuscitation. Recent literature has raised concerns about complications from over-resuscitation described as "fluid creep." Again, adequate fluid resuscitation is the goal.

Other management for severe burns includes nasal gastric tube placement as most patients will develop ileus. Foley catheters should be placed to monitor urine output. Cardiac and pulse oximetry monitoring are indicated. Pain control is best managed with IV medication. [13]Finally, burns are considered tetanus-prone wounds and tetanus prophylaxis are indicated if not given in the past five years. In any severe flame burn, you should always consider possible associated inhalation injury, carbon monoxide or cyanide poisoning (see Inhalation Injury chapter).

Severe burn wound management should be directed to your local burn center. In general, the burns should be gently cleansed and covered with clean dressings. Extensive debridement and application of topical antimicrobial creams or ointment are not needed if the patient is urgently transferred to a burn center because they will need to do their own burn assessment once the patient arrives.

In certain situations, an emergent escharotomy may be necessary before transfer. Escharotomy is a surgical procedure performed to relieve the constricting effect of full-thickness burns. Because full thickness burns are firm, leathery and nonpliable, they can limit the typical swelling that would occur. This can create a compartment syndrome effect if the burns surround an extremity or an abdominal compartment syndrome effect if the burns surround the abdomen. If the burn involves extensive areas of the chest, then adequate ventilation may be impossible. In such cases, escharotomy should be done to relieve the constriction effects and allow for adequate circulation or ventilation. An escharotomy is done by making an incision through the firm burn eschar, deep enough into the fat layer to allow the eschar to split open. This can be done at the bedside without anesthetic because the burn injury has destroyed the nerve fibers and the skin has lost sensation. Incisions are made on the medial and lateral sides of extremities and digits, along with the axillary lines and parallel to the clavicles on the upper chest, and along the lateral abdominal walls on the abdomen.

Complications

Deep or extensive burns can lead to many complications, including:

- Breathing problems

- Bone and joint problems

- Dangerously low body temperature

- Infection and sepsis

- Low blood volume

- Scarring

- Tetanus

Infection is the most common complication. In order of frequency, potential complications include: pneumonia, cellulitis, urinary tract infections and respiratory failure. Pneumonia commonly occurs in those with inhalation injuries.

Other complications may include:

- Anemia secondary to full thickness burns of greater than 10% TBSA is common.

- Electrical burns may result in compartment syndrome or rhabdomyolysis.

- Blood clotting in the veins of the legs occurs in 6-25% of patients with extensive burns.

- The hypermetabolic state that may persist for years after a major burn may result in a decreased bone density and muscle mass.

- Keloids may form subsequent to a burn.

- Following a burn, psychological trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder my develop.

- Scarring may aresult in a disturbance in body image.

- In the developing world, significant burns may result in social isolation, poverty, and child abandonment.

Clinical Significance

Burns are often preventable. Treatment depends on severity. Superficial burns may be managed with cleaning and pain medication, while major burns may require prolonged treatment. Partial-thickness burns require cleaning with soap and water, followed by dressings. Full-thickness burns usually require surgical treatments, such as skin grafting. Extensive burns often require large amounts of intravenous fluid, due to capillary fluid leakage and tissue swelling. The most common complications of burns involve infection. Burns are considered tetanus-prone wounds and tetanus toxoid should be given every five years, if not up to date.

Burns often become infected; tetanus toxoid should be given if it is not current.

Burns account for over 30 million injuries per year in the U.S.A. This resulted in about 3 million hospitalizations and 240,000 deaths per year. In the United States, approximately 96% of those admitted to a burn center survive their injuries, but prompt treatment is required. It is important for all clinicians to be familiar with the evaluation and appropriate referral of the burned patient.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Managing burns requires an interprofessional team that includes an intensivist, burn specialist, pain specialist, infectious disease expert, emergency department physicians, wound care nurses, dietitian, and physical therapists. In general, 2nd and 3rd-degree burns require more care than 1st-degree burns.

The most common complications of burns involve infection. Burns are considered tetanus-prone wounds and tetanus toxoid should be given every five years, if not up to date. Burns affect the physiology of the entire body and often require management from a variety of specialists including the dietitian. Even after recovery, many require extensive physical therapy to regain muscle mass and function. Because burns have a profound effect on aesthetics, all patients should be seen by a mental health nurse at regular intervals. The outcomes after burn injury depend on age, the extent of the injury, type of burn, and involvement of other organs. It is important for all clinicians to be familiar with the evaluation and appropriate referral of the burned patient.[14][15][16] (Level V)