Celiac Plexus Block

- Article Author:

- Reena John

- Article Author:

- Bruce Dixon

- Article Editor:

- Ryan Shienbaum

- Updated:

- 8/25/2020 12:28:50 AM

- For CME on this topic:

- Celiac Plexus Block CME

- PubMed Link:

- Celiac Plexus Block

Introduction

First described as a method of providing surgical anesthesia to the upper abdomen, the celiac plexus block (CPB) has been in practice for nearly a century. The celiac plexus block is being used as an adjunct to managing abdominal visceral pain in a multimodal fashion. The celiac plexus is comprised of three pairs of ganglia: the celiac ganglia, superior mesenteric ganglia, and aorticorenal ganglia. Several abdominal organs receive autonomic innervation through the celiac plexus. The celiac plexus block aims to target the afferent nociceptive fibers and is suitable to be used as both a diagnostic as well as a therapeutic tool for managing intraabdominal pain.[1][2]

Anatomy and Physiology

Due to its vast web of nerve fibers, the celiac plexus is also referred to as the solar plexus. Many abdominal organs receive autonomic innervation via the celiac plexus including the liver, gallbladder, stomach, pancreas, spleen, both kidneys, the entire small bowel, and the first two-thirds of the large bowel. The celiac plexus is made up of the celiac, aortic, renal, and superior mesenteric ganglia and is positioned anterolateral to the aorta diaphragm at the level of the L1 vertebrae. The celiac plexus consists of both parasympathetic and sympathetic nerves. Sympathetic innervation of the celiac plexus originates from the anterolateral horn of the spinal cord at the level of T5 to T12.[3][4]

Indications

The celiac plexus block is indicated in a setting of intractable abdominal pain which is nonresponsive to less aggressive analgesic interventions; often these patients require high dose opioid therapies with little clinical benefit. This block targets visceral afferent pain fibers from the liver, gallbladder, omentum, pancreas, mesentery, and digestive tract beginning with the stomach and terminating at the mid-transverse colon. The indications for a celiac plexus block include treatment of intractable intra-abdominal pain, including pain in the setting of malignant and benign neoplasms involving the pancreas, biliary tree, retroperitoneal organs, and other abdominal organs. One of the most common indications for the celiac plexus block is the treatment of abdominal pain associated with pancreatic cancer. The utilization of celiac plexus blocks to alleviate pain secondary to chronic pancreatitis remains controversial. When choosing an injectate, local anesthetics and steroids are reserved for patients with benign pathology whereas neurolytic celiac plexus blocks are typically reserved for cancer-related pain.

The major indications for celiac plexus block (CPB) are abdominal pain which is nonresponsive to less aggressive analgesic interventions, and often these patients are nonresponsive to high dose opioid therapies. This block targets the liver, gallbladder, omentum, pancreas, mesentery, and the digestive tract from the stomach all the way to the transverse large colon. CPB is indicated in the setting of malignancy as well as neoplasms of benign origin. The indications for a CBP include treatment of visceral abdominal pain and malignancies involving the pancreas, biliary tree, retroperitoneal organs, and other abdominal organs. One of the most common indications for the CPB is the treatment of pain that caused by pancreatic cancer. The use of CPB for pain secondary to chronic pancreatitis is still controversial. Local anesthetics and steroids are reserved for patients with benign pathology whereas neurolytic CPB is typically reserved for cancer-related pain.[5][1]

Contraindications

Many patients that could benefit from this procedure have other comorbidities and underlying processes that need to be considered before performing this block. Cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy or radiation treatments may be immunocompromised, making them highly susceptible to infection secondary to injection. Patients may also be coagulopathic or thrombocytopenic, posing an increased risk of significant bleeding. Even with the use of CT guidance and fluoroscopy, one must be cognizant of metastatic disease and other possible masses that could be injured or vascular.

Contraindications to CPB are similar to those of all other blocks and include patient refusal or inability to consent, coagulopathy or anticoagulation use, ongoing infection, and abnormal anatomy obscuring the trajectory of the needle and making it difficult or near impossible to target the appropriate structures.

Technique

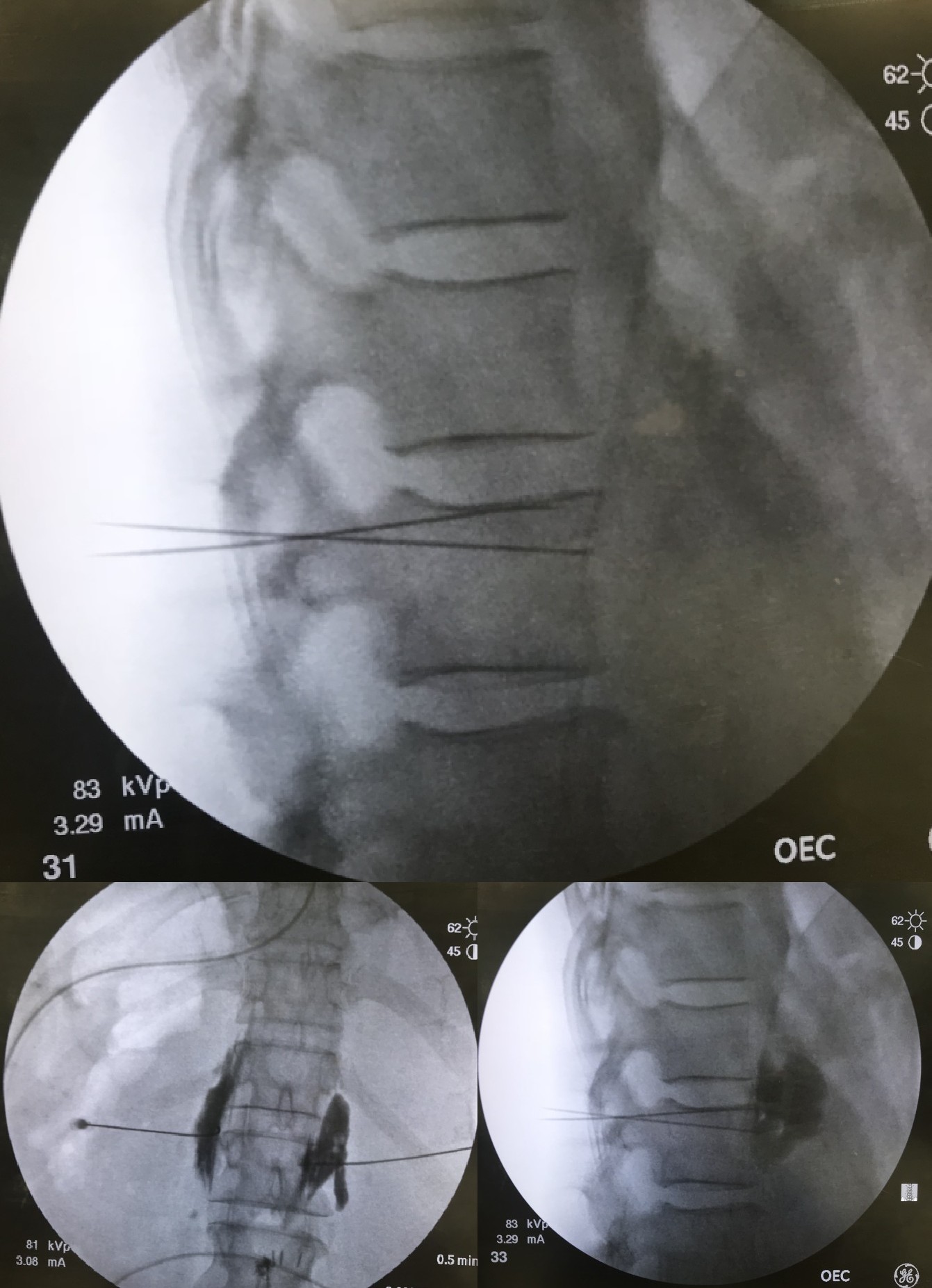

Several approaches have been described to perform the celiac plexus block (CPB). Two of the most commonly practiced approaches are the posterior para-aortic approach and the anterior para-aortic approach (which will be discussed in more detail below). The anterior para-aortic approach should be considered in patients with advanced disease who may have abdominal discomfort and are unable to lie in the prone position or patients who underwent abdominal surgery. A diagnostic block consisting of local anesthetic should be performed before the neurolytic block, to confirm efficacy and pain relief attributable to the block. Generally, within the literature, alcohol is the preferred agent for neurolytic celiac plexus blocks as it is considered to be more effective.[2]

Posterior Para-Aortic Approach

The patient should be placed in the prone position with support under the abdomen to increase the kyphosis of the thoracic spine. Before performing the block, make a note of the following anatomical landmarks: midline spine and vertebral bodies, iliac crests, 12th rib, and lateral border of the paraspinal muscles. The patient's skin should be thoroughly disinfected and the area should be draped appropriately. With radiographical tools, identify the T12 and L1 vertebral bodies. The inferior border of the 12th rib should be identified and marked in a sterile fashion. A skin wheal should be placed at the inferior border of the 12th rib approximately 6 to 8 cm from the midline. An appropriate spinal type needle should be advanced at a 45-degree angle from posterior to anterior toward the ventral surface of the T12-L1 intervertebral space until the vertebral body is contacted. Once the vertebral body has been contacted the spinal needle should be advanced approximately another 1 cm further into the prevertebral fascial plane. Once the needle is in the desired position, the practitioner can confirm appropriate local by the spread of contrast under CT or fluoroscopic guidance. A diagnostic block with local anesthetic or a therapeutic neurolytic block can be performed at that time. In the instance of a unilateral block, the left-sided approach has shown to be reliable. A bilateral block can be performed if the unilateral block does not provide sufficient results.

Anterior Para-Aortic Approach

This approach is especially helpful in patients with advanced disease who may have abdominal discomfort and are unable to lie in the prone position or in those patients who underwent abdominal surgery. With the patient in the supine position, the needle’s trajectory is mapped via CT or fluoroscopic guidance. Subsequently, the skin should be disinfected and prepared similarly to that of the posterior para-aortic approach. A local anesthetic skin wheal should be injected into the abdominal wall just anterior to the T12 vertebral body. An appropriate spinal needle should be inserted and directed toward the abdominal aorta, the needle’s course will typically encounter abdominal viscera including bowel, stomach or liver. With the needle tip’s final position anterior to the aorta and diaphragmatic crura, the neurolytic agent is injected into the antecrural space. This approach is often quicker than the posterior para-aortic approach and well tolerated by patients; however, its use is limited by the potential for organ injury.

Complications

While complications are rare, one must be aware of possible complications that may result from a celiac plexus block. Complications that have been noted in the setting of celiac plexus block (CPB), despite the use of CT guidance, include orthostatic hypotension, intravascular injection (a complication that can occur with any block), nerve root injury, paresthesias, intrathecal or epidural injection, injury/trauma to nearby organs, diarrhea, pneumothorax, vascular injury, infection/abscess formation, muscle trauma, retroperitoneal hematoma, paraplegia, and local anesthetic toxicity with central nervous system and cardiovascular compromise. There is always the risk of an unsuccessful block. Orthostatic hypotension, which is the most common complication, can be minimized with adequate hydration. Complete sympathetic denervation of the gastrointestinal tract will likely cause a patient to develop increased peristalsis due to unopposed parasympathetic nervous system activity.[6]

Clinical Significance

Pancreatic cancer is the second most common abdominal cancer in the United States. The pain experienced by those with pancreatic cancer has been described as substantial and often uncontrolled by medication. The use of a celiac plexus block with neurolysis can improve the pain experienced by these patients, decrease overall opioid consumption, and improve patient satisfaction.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

In a team setting, it is imperative that closed-loop communication exists. All patient should have a proper timeout performed. The name of the patient, date of birth, any pertinent allergies, and what procedure the patient is having done should all be confirmed between all providers (anesthesiologist, nurse, surgeon, et al.) as well as with the patient. All consents should be signed after thorough risks, benefits, and expectations have been explained in detail to the patient. It is crucial that site verification and laterality is confirmed before beginning any procedure. The implementation of guidelines and checklists have proven to reduce the occurrence of adverse outcomes such as surgeon-anesthesiologist miscommunications and wrong-site/wrong-side regional anesthesia procedures.[7][8] (Level I)

It is important that this block is done with some form of visualization so the target can be identified as well as surrounding structures. While most providers perform the celiac plexus block under CT/fluoroscopy guidance, some studies show that endoscopic ultrasound guidance has better outcomes including longer duration of pain control as well as being a safer effective option with reduced costs.[9][10] (Level II)