Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Celiac Trunk

- Article Author:

- Nanki Ahluwalia

- Article Author:

- Ali Nassereddin

- Article Editor:

- Bennett Futterman

- Updated:

- 9/27/2020 9:10:25 AM

- For CME on this topic:

- Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Celiac Trunk CME

- PubMed Link:

- Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Celiac Trunk

Introduction

The abdominal aorta predominantly provides blood supply to the upper abdominal cavity and its contents. Its major branches include the celiac trunk, superior mesenteric artery, and inferior mesenteric artery. The first major branch, which comes off anteriorly at the T12 level, is the celiac trunk. It supplies oxygen-rich blood to the spleen, and structures derived from the embryonic foregut. The celiac trunk is a critical artery whose anatomy can vary, and therefore, intricate knowledge of its branches and variations is important in facilitating radiographic interpretations and in limiting surgical complications.

Structure and Function

The celiac trunk, also known as the celiac artery, is a short vessel that arises from the aorta and passes below the median arcuate ligament, just as the aorta enters the abdomen at the level of the T12 vertebra. The celiac trunk measures about 1.5cm to 2cm in length.[1][2] It supplies blood to the foregut, namely:

- Distal esophagus to the second part of the duodenum

- Liver

- Pancreas

- Gallbladder

- Spleen

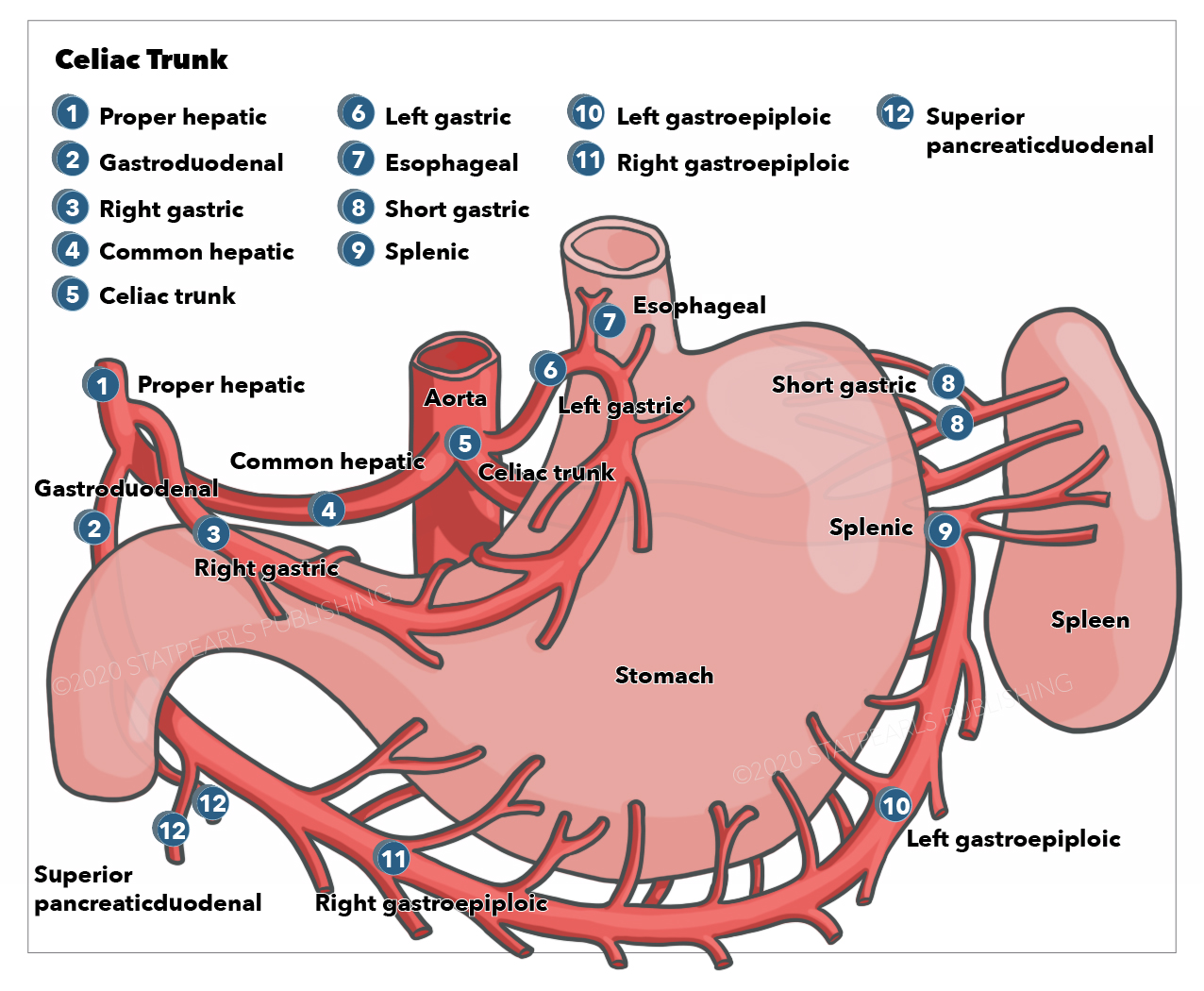

The celiac trunk classically divides into three major branches:

- Left gastric artery: This artery is responsible for the blood supply to the lesser curvature of the stomach as well as the lower esophagus. It anastomoses with the right gastric artery.

- Common hepatic artery: This artery, through its many branches, supplies the liver, pylorus of the stomach, gallbladder, duodenum, and the pancreas.

- Splenic artery: This artery offers multiple branches to the upper and middle parts of the greater curvature and fundus of the stomach as well as to the pancreas. This artery ends its course by providing oxygenated blood to the spleen.

Embryology

The arterial system undergoes various modifications within an embryo during its growth. Intraembryonically, the arterial system consists of aortic arches, and the central and dorsal aortas, that are all continuous with each other. Arising from the dorsal aorta are paired ventral segmental arteries, some of which fuse to form the median vessels. These vessels then give rise to the three main arterial systems: celiac trunk, superior mesenteric artery, and inferior mesenteric artery.

By the 4th week of embryologic development, the gastrointestinal tract has divided into foregut, midgut, and hindgut. Foregut extends from the esophagus to the ampulla of Vater, midgut extends from the distal duodenum to the proximal two-thirds of the transverse colon, and hindgut extends from the distal one-third of the transverse colon to the rectum. Foregut, midgut, and hindgut will each have a unique blood supply.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Blood supply

The three major branches of the celiac trunk include the left gastric, splenic, and common hepatic arteries. These arteries constitute the main blood supply to the foregut and the spleen. The left gastric artery gives off esophageal branches that supply the lower part of the esophagus. It then travels along the lesser curvature of the stomach to form an anastomosis with the right gastric artery. The splenic artery travels posterior to the stomach and gives rise to the left gastroepiploic artery, which supplies the greater curvature of the stomach. It also gives rise to pancreatic branches that supply the tail and body of the pancreas. The short gastric artery is another branch of the splenic artery, and it supplies blood to the fundus of the stomach. It is important to note that the short gastric artery does not anastomose with any other arteries. As a result, the fundus of the stomach does not have a dual blood supply, and any obstruction to the splenic artery will lead to ischemia of the fundus.[1]

The common hepatic artery, which is the only arterial source to the liver, gives off the proper hepatic and gastroduodenal arteries. The proper hepatic artery gives rise to the right gastric and right and left hepatic arteries. The cystic artery is usually a branch of the right hepatic artery. 1.2% of the time, it can originate from the left gastric artery.[3] The right gastric artery delivers blood supply to the pylorus and the lesser curvature of the stomach. The right and left hepatic arteries supply the corresponding liver lobes. The cystic artery supplies the gallbladder. The gastroduodenal arteries give off the right gastroepiploic and the superior pancreaticoduodenal arteries. The right gastroepiploic artery will supply the greater curvature of the stomach, whereas the superior pancreaticoduodenal artery will supply the head of the pancreas.[1] The pancreatic head is the most common site of pancreatic adenocarcinoma and is usually the part of the pancreas removed in a Whipple procedure.

Lymphatics

Celiac lymph nodes are located around the celiac trunk and drain lymph from the liver, gallbladder, stomach, spleen, and pancreas into the cisterna chyli, which eventually drains into the thoracic duct.

Nerves

Celiac ganglia are two nerve bundles located around the celiac trunk at the T12-L1 spinal levels. They represent a mass of nerve cell bodies that are part of the autonomic nervous system and are responsible for innervation of the gastrointestinal tract and abdominal organs. They carry sympathetic input to abdominal parenchyma and are vital for coordinating digestive functions of the gastrointestinal tract, including motility, secretion, and absorption.[4]

Muscles

The celiac trunk does not supply blood to any muscles of the body. It is only responsible for providing blood to abdominal viscera.

Physiologic Variants

Besides the classic presentation of the celiac trunk trifurcating into its branches, there have been numerous reported cases of variations in the celiac trunk's branching. These cases include, but are not limited to, celiac trunk bifurcation into the hepatic artery and splenic artery, the absence of the trunk itself as it may arise commonly with the superior mesenteric artery (celiacomesenteric trunk).[5][6] The celiac trunk may also give rise to inferior phrenic arteries. These arteries may spring either from the aorta or the celiac trunk.

During surgical procedures in the abdomen, vessel ligation and anastomosis are crucial. Surgeons must have intricate knowledge of the different variations in the vascular anatomy of the celiac trunk, which will help facilitate radiographic interpretations and will also limit complications of surgery.

Surgical Considerations

Most patients present with asymptomatic vascular anomalies of the celiac trunk. However, vital knowledge of the celiac trunk, its branches, and vascular variations is essential for any surgical procedures involving the upper abdomen. These procedures include a liver transplant, diagnostic procedures like angiography for gastrointestinal bleeding, or celiac axis compression syndrome. Recognition of variations in abdominal arteries that supply the liver, pancreas, gallbladder, and spleen can help in reducing the blood loss during surgical procedures involving these areas.[6][7] The vascular anatomy of the celiac trunk also plays a crucial role in arterial anastomoses during surgery.

Clinical Significance

Celiac Artery Compression Syndrome

It is also commonly known as celiac axis syndrome, median arcuate ligament syndrome (MALS), Marable syndrome, and Dunbar syndrome. This syndrome characteristically presents as angina localized to the upper abdomen due to the compression of the celiac artery by diaphragmatic crura.

The median arcuate ligament is a fibrous arch that connects the right and left diaphragmatic crura around the aorta, at the base of the diaphragm. If this ligament is low lying due to its highly variable locations, it can compress or distort the celiac trunk in a downward angle resulting in an unpleasant or excruciating epigastric pain. The pain is often relieved when in the standing position and becomes exacerbated when in the supine position. This syndrome commonly presents in the 20 to the 40-year-old patient population. In specific individuals, this may also result in mesenteric ischemia. The most common complaint alongside epigastric pain is postprandial pain, which results in weight loss.

Computed tomography (CT) angiography would reveal focal stenosis with a characteristic hook-shaped appearance due to the distorted shape of the celiac trunk on its superior surface. Since the celiac trunk can have a similar appearance upon expiration in a healthy patient, it is important to make the diagnosis of celiac artery compression syndrome by correlating the imaging findings with patient history.

Treatment of this syndrome via laparoscopic surgical decompression by dividing the median arcuate ligament and is usually reserved for symptomatic patients.[5]

Celiac Aneurysm

Although rarely found in clinical cases, celiac artery aneurysm can occur as a form of splanchnic artery aneurysm. A celiac aneurysm is typically asymptomatic until it ruptures. Since the rupture of the celiac trunk aneurysm carries high morbidity and mortality rates, early recognition of this vascular anomaly becomes crucial. It is often found incidentally on diagnostic imaging studies such as arteriography or post rupture in autopsies.

Celiac Trunk Dissection

Most commonly, the cause of a celiac trunk dissection is iatrogenic. However, often comorbidities such as atherosclerosis, hypertension, pre-existing vascular diseases such as fibromuscular dysplasia, and even pregnancy can be predisposing factors to arterial dissection. Alternative factors can also include trauma due to a sudden increase in intra-abdominal pressure, or they can be mechanical. Celiac trunk dissections are frequently asymptomatic but may present with abdominal pain if there is the involvement of bowel ischemia secondary to rupture of other abdominal arteries such as splenic, renal, or superior mesenteric arteries.

The optimal means of diagnosing celiac trunk dissection is CT with contrast or CT angiography. However, other imaging studies, such as magnetic resonance (MR) angiography or sonography, can also be considered. On diagnostic imaging, the most common finding for the dissection is an intimal flap and/or a presence of mural thrombus in the lumen of the celiac trunk.

Surgery is usually needed to manage celiac trunk dissection to prevent further acute complications such as rupture, intestinal ischemia, or chronic complications such as arterial stenosis. However, if the clinician diagnoses the dissection as limited, the aim shifts toward preventing thromboembolic events. In such cases, treatment is conservative with the use of anticoagulation and anti-hypertensives to control the blood pressure. An additional option can also include evaluating the collateral supply and managing the endovascular itself.[8]

Peptic Ulcer Disease

Gastric or duodenal ulcers are painful sores that occur mainly as a result of Helicobacter pylori infection, long-term non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use, or tobacco smoking. Patients will report epigastric abdominal pain and early satiety. With gastric ulcers, the pain usually increases after meals, while the pain usually decreases after meals with duodenal ulcers. Gastric ulcers most commonly occur on the lesser curvature of the stomach, which is supplied by the right and left gastric arteries. Duodenal ulcers most commonly occur on the posterior wall of the duodenum, an area supplied by the gastroduodenal artery. The gold standard for testing is Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD). Management typically includes H2-receptor antagonists and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs).