Cerebrospinal Fluid Leak

- Article Author:

- Michael Severson

- Article Editor:

- Margaret Strecker-McGraw

- Updated:

- 8/10/2020 10:52:05 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Cerebrospinal Fluid Leak CME

- PubMed Link:

- Cerebrospinal Fluid Leak

Introduction

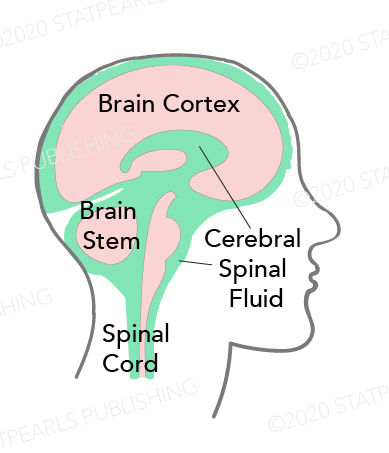

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is a clear protein- and glucose-rich liquid in the subarachnoid space of the central nervous system. It is found in the ventricles, surrounding the brain, and within the central spinal column. CSF regulates central nervous system temperature, cushions the brain and spinal cord, and provides a delicately balanced buoyant force that allows the brain to retain its shape and circulatory integrity despite its weight and lack of intrinsic rigid support.[1] A leak in this system, therefore, can be detrimental to brain blood supply and function and can increase the risk of direct trauma to brain parenchyma due to loss of fluid cushion. Additionally, the presence of CSF leak indicates the need for further evaluation and management as it may be due to a frontobasilar or temporal skull fracture. Open communication of the subarachnoid space with CSF leak presents a pathway for life-threatening central nervous system (CNS) infection including meningitis.

Etiology

A cerebrospinal fluid leak can occur whenever there is open communication between the subarachnoid space and other spaces via meningeal disruption. The most common cause of leaking cerebrospinal fluid is a structural compromise secondary to craniofacial trauma, making up 80% of CSF leaks. Iatrogenic causes make up 16% of CSF leaks, with the last 4% of leaks due to varied etiologies, including spontaneous leak and congenital defects.[2]

Craniofacial trauma can lead to varied presentations of CSF leak, determined primarily by injury location and mechanism of action. Anterior skull base fractures are frequently associated with moderate-to high-velocity impact. They are, thus, more commonly associated with CSF leak compared to injuries to other locations due to the generally more extensive force of trauma, such as involvement in a motor vehicle accident. The cribriform plate, ethmoid bone, and frontal and sphenoid sinuses are thin and closely associated with the dura. Thus, trauma can easily disrupt both osseous structures and dura. Less frequently, fractures of the temporal bone are associated with dural disruption which can also result in CSF leak. Rarely, injury and disruption to the orbit can result in CSF occulorrhea.[3]

Iatrogenic CSF leaks occur most frequently as sequelae to functional endoscopic sinus surgery with the cribriform plate and ethmoid bone being the most commonly injured, followed by the frontal and sphenoid sinuses.[2][4] Neurosurgical interventions also contribute to iatrogenic leaks, especially with the increased prevalence of endoscopic transnasal pituitary surgeries. In one study, pituitary tumor resection made up nearly half of cases where tumor removal led to confirmed CSF leak.[4] Spinal CSF leaks may also occur after certain procedures such as lumbar punctures, epidural anesthesia, or spinal surgery.

Epidemiology

Spontaneous CSF leaks occur without an obvious inciting event. Increasingly, spontaneous leaks are attributed to underlying conditions that result in increased intracranial pressure (ICP) such as idiopathic intracranial hypertension (idiopathic intracerebral hypertension - pseudotumor cerebrii). This condition is frequently associated with obesity and female sex; In some studies, 60-70% of subjects presenting with spontaneous leaks were female and body mass index (BMI) was overweight or obese; in two studies the mean BMI was approximately 35.[4][5][6] These leaks were most likely secondary to an erosion of thin bony structures discussed above due to chronically increased ICP.

Pathophysiology

The CSF coming out of the defect in the cranial cavity due to some cause migrates along the nasal cavity either into the anterior nares or nasopharynx.

History and Physical

As most CSF leaks are secondary to either accidental or iatrogenic trauma, the history of a patient presenting with rhinorrhea or otorrhea should raise suspicion for CSF leak; thus one should obtain a recent history of trauma or a surgical procedure. The most common presenting symptom across all causes is clear rhinorrhea that may be accompanied by a headache. In those with spontaneous leaks, presentation frequently includes a pressure-like headache that may be positional in nature as well as pulsatile tinnitus.[7]

Evaluation

Evaluation of a suspected leak should include testing of rhinorrhea or otorrhea for beta-2 transferrin, a compound found only in CSF and perilymph making it a highly specific and sensitive test. If negative, there is a low likelihood of a leak.[8][9]

Glucose testing of rhinorrhea liquid was more frequently done in the past but has poor sensitivity and specificity when compared to beta-2 transferrin.

If beta-transferrin is positive during an acute leak or if there is a high index of suspicion, imaging is indicated to localize the source. High-resolution CT (HRCT) of paranasal sinuses and temporal bone is typically sufficient for identifying single osseous defects. If multiple defects are suspected on HRCT, CT cisternography is useful to localize the lesions further. If initial CT is suspicious for meningoencephalocele, magnetic resonance cisternography is highly sensitive for soft tissue findings. If the leak is intermittent but active, HRCT is still the first-line imaging test of choice, but if the suspected leak is inactive at the time of imaging, consider contrast-enhanced MR cisternography or radionucleotide cisternography.[10]

In cases of chronic CSF leak or intracranial hypotension, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain may show intracranial pachymeningeal thickening and enhancement with contrast, subdural fluid collections, and downward displacement of the brain. MRI of the spine can also show dural collapse and may demonstrate CSF leakage from spinal dural defects.[11]

Treatment / Management

Cases of CSF leak are managed according to their etiology. In cases of craniofacial trauma, it has been posited that since a number of these resolve with no intervention that conservative management and observation should be employed. However, the risk of developing meningitis in these patients is up to 29%, so this course should be pursued with caution.[12] For cases of spontaneous leak due to elevated intracranial pressures, multiple therapies have been employed. These include acetazolamide, the use of lumbar shunts or repeat lumbar punctures to lower ICP, endoscopic repair, and in cases of refractory or particularly high ICP, ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunts. VP shunts can be effective but have relatively high complication rates.[4]

In cases of iatrogenic injury during intracranial surgery, the obvious treatment is the repair of the affected site which may require multiple procedures to fix.[13] In cases with basilar skull fractures that are surgically managed, an endonasal endoscopic approach has a first attempt success rate ranging from 80 to 91%. The remaining cases may need further endoscopic revision with less than 10% of cases requiring open surgical revision.[6] Overall success rates range from 99 to 100%.[4][6] The surgical failure rate is higher among those with elevated ICP.[14]

Differential Diagnosis

The presentation of clear rhinorrhea and/or a headache is common to many conditions. Those that should be specifically considered are:[15][16]

- Allergic rhinitis

- Benign intracranial hypotension

- Carotid or vertebral artery dissection

- Infectious etiologies such as the common cold

- Meningitis

- Posttraumatic headache

- Spontaneous intracranial hypotension

- Subarachnoid hemorrhage

- Vasomotor rhinitis

Prognosis

Complications

The most serious potential complication of CSF leak is meningitis. This risk appears to be highest in the preoperative period for those with confirmed CSF rhinorrhea with those sustaining traumatic injuries being at the highest risk of around 30%. However, the risk of meningitis remains at 19% in those with persistent CSF leak and such persons remain at risk until successful operative closure.[18]

Deterrence and Patient Education

The usefulness of deterrence and patient education is limited due to the varied etiologies as well as the common presenting symptoms of a headache and clear rhinorrhea being nonspecific. However, public health education regarding the prevention of trauma such as motor vehicle accidents as well as reduction of obesity would likely lead to a decreased number of traumatic or obesity-related CSF leaks.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

CSF leak is a condition that involves many areas of healthcare. Initial presentation of a patient may occur at any level of the care center and any provider, including physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants. Laboratory technicians interpret CSF samples collected for testing. Radiologic technicians are instrumental in obtaining proper studies which are then interpreted by radiologists. Surgeons, interventional radiologists, and surgical technicians then provide definitive operative management. Throughout the presentation, workup, and treatment of a patient, pharmacists review and nurses administer medications and monitor patient vital signs. Because many of these patients' hospital stays may be prolonged, effective communication is important for preventing medical errors and reducing patient harm.