Clonorchis Sinensis

- Article Author:

- Victoria Locke

- Article Editor:

- Melissa Richardson

- Updated:

- 9/12/2020 7:15:13 AM

- For CME on this topic:

- Clonorchis Sinensis CME

- PubMed Link:

- Clonorchis Sinensis

Introduction

Clonorchis Sinensis is also known as the Chinese liver fluke. These are most commonly found in Eastern Asia but are also commonly found in Russia. These liver flukes are common parasites of fish-eating mammals. Cats and dogs of endemic areas are the most common hosts but can be passed to humans who eat infected fish. When infected, C. Sinensis will live within the biliary system of humans. These parasites, when present with a large parasite burden in humans, can have serious complications if not found and treated promptly.[1][2]In parts of Asia, the fluke worms are a public health problem.

Etiology

Causes of clonorchiasis are mostly limited to the ingestion of fish that are encysted with C. Sinensis in endemic regions of the world, including East Asia.

The Lifecycle of C. Sinensis

Eggs of C. Sinensis are consumed by water snails, which mature and are released from the snail into the water. These encyst into the flesh of freshwater fish and continue to mature. The infected fish is then ingested by a higher mammal such as humans, where the metacercariae sit in the duodenum and ascend through the biliary tree. Complete maturation can take up to a month. The adult flukes reside in the biliary tree. The life cycle can take up to 3 months before eggs will show up in sputum or feces of an infected adult.[3]

Snails are an important host for C.sinensis, especially in China. These snails are often found in the local waterways, ponds, lakes and paddy fields. The mature cercariae are released from snails and may invade fish, which are then consumed by humans and many other carnivorous animals. It is eating raw or uncooked freshwater fish that can lead to parasitic infection. The worms can survive for long periods in the duodenum and bile ducts. Once a large parasite burden occurs, the patient may present with abdominal discomfort, indigestion, jaundice and bile duct obstruction.

Epidemiology

C. Sinensis is endemic to the Eastern hemisphere of the world, mostly East Asia and parts of Russia. Studies estimate that about 35 million people may be infected in the world. Prevalence in specific locations of East Asia varies widely, with occurrence rates as high as 95% in some small villages of Thailand. It is estimated that 200 million people are at risk, 15 million are infected, and that about 2 million show symptoms. Additionally, there are over 31 types of fish and shrimp that are hosts of C. Sinensis, many of which are common fish that are consumed by humans and are served restaurants in endemic regions. Infection rates show a preference for males (2.94%) over females (1.84%), and for those whom raw fish is a major part of their diet. The most serious and threatening infections tend to favor those between ages 40 to 60 and older. It is estimated in Asia that nearly 6000 people die from complications of C. Sinensis infection each year.[4][2]

Pathophysiology

C. Sinensis is one of the most common parasitic infections in the world. Because of its very close relationship with cholangiocarcinoma, it is a very serious public health issue. Humans, who are the definitive host, become infected by ingestion of raw, undercooked fish that is encysted with C. Sinensis. The adult form of C. Sinensis resides in the biliary of humans. They may live the ducts for up to 20 years and can grow as large as 25 mm by 5 mm. The exact pathogenesis of C. Sinensis infection to cholangiocarcinoma is unclear. While liver abscesses from C. Sinensis are not common, there have been several cases showing these species can also produce these. Liver abscesses can be particularly dangerous to remove as they can cause anaphylaxis if they are punctured. Serious complications such as cholangiohepatitis and cholangiocarcinoma are thought to result from chronic irritation resulting in hyperplasia, dysplasia, and fibrosis. Inflammatory immune responses are known to be causes of carcinoma. Nitric oxide formation and parasitic secretory products are several theories behind the mechanism of carcinogenesis from C. Sinensis.[2][5]

History and Physical

The pathologic and clinical consequences of infection are directly related to the intensity and duration of infection. Most infected patients are considered to have an innocuous infection (less than 100 flukes), and rarely have symptoms. Five to ten percent of infected humans can have a very heavy parasite load. These patients can present with vague symptoms: right upper quadrant abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, malaise, and fevers. This occurs about 10 to 30 days after the ingestion of an infected fish. When these symptoms do occur, they usually are present for 2 to 4 weeks, with eggs becoming detectable in stool after 3 to 4 weeks. Peripheral eosinophilia may be present in some patients. Chronic symptoms are often observed in patients with a heavy burden of liver flukes. These symptoms are generally a result of chronic mechanical and physical injury of the bile ducts.

Chronic symptoms include vague abdominal pain, anorexia, increased bile acids, weight loss, dyspepsia, and diarrhea. Often, elevated alkaline phosphatase may be present. The heavy parasite burden can be particularly dangerous. High concentrations in the gallbladder can result in cholecystitis. Chronic obstruction of the bile ducts can result in ascending cholangitis, cholangiohepatitis, and cholangiocarcinoma. Dead flukes can also serve as a nidus for stone formation, forming pigment stones.[2][6]

Evaluation

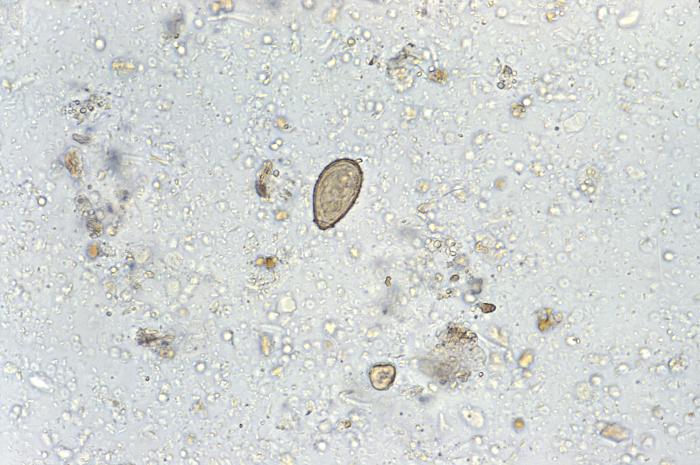

The diagnosis is generally made from the presence of ova and parasites found in stool samples, duodenal aspirate or flukes found in biliary secretions are diagnostic. Standard diagnostic tests include a direct fecal smear, Kato-Katz method, which is a method of preparing stool samples where stool is pressed through the mesh, and the remaining sample is a piece of cellophane soaked in glycerol which clears the stool from the eggs. The gold standard diagnosis is through formalin ethyl-acetate concentration technique (FECT). Worms may also be found in endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP).[7][3]

Serological tests do exist to establish a diagnosis of C.sinensis. Today PCR techniques are being employed to make a rapid diagnosis within 24-48 hours.

Imaging including ultrasound, CT, MRI, and harmonic imaging are also used to determine the location, progression, and extent of the infection.

Treatment / Management

The most effective treatment for clonorchiasis is praziquantel 75 mg/kg orally three times per day for 1 to 2 days. This regimen cures about 99% of infected patients. Close to one hundred percent of patients are cured with a second treatment if they were not completely cured with the first treatment. Patients with severe or advanced sequelae of this disease, such as ascending cholangitis, may require biliary drainage or surgery. Symptoms of cholecystitis may require cholecystectomy. Patients’ family members and close contacts should also be tested for infection because it is more than likely that they may have eaten the same contaminated food. Liver abscesses, although rare with this parasite, should be managed carefully. The abscess should not be percutaneously aspirated as there is a risk of spillage into the abdomen. Patients with liver abscesses may require segmentectomy of the liver.[8][9]

Praziquantel does have unpleasant side effects and thus in some cases other drugs like artesunate, mebendazole and tribendimidine are also used.

Researchers have been trying to develop a vaccine but so far they have only been tested in animals.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes acute hepatitis, cholecystitis, choledocholithiasis, cholangiocarcinoma, primary sclerosing cholangitis, and other parasitic infections, including schistosomiasis, strongyloidiasis, and ascariasis.[1]

Prognosis

The prognosis for most patients is good if they remain compliant with the medications. Those who do require surgery have a slightly longer recovery period and may develop surgery-related complications.

Complications

The liver flukes reside within the biliary tree and cause obstruction, inflammatory irritation, and fibrosis, which, when present for an extended time, can eventually lead to cholangiocarcinoma. Cholangiocarcinoma is the most severe and lethal outcome of a burdensome C. Sinensis infection. This will usually present with vague symptoms such as right upper quadrant pain, nausea, vomiting, and obstructive jaundice. The mainstay of treatment for cholangiocarcinoma is surgical resection. The specific required procedure is dependent on the location of the lesion and is discussed more in-depth under the cholangiocarcinoma article.[3]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Prevention of C. sinensis infection is heavily based on patient education and proper food preparation. Endemic areas promote education with public awareness programs, health guide booklets, and educating school children. These educational programs are enforcing proper food preparation and avoidance of undercooked or raw fish. Removal of farm animals from nearby fish farms and recognition of symptoms is also essential. These areas must undergo cultural changes to begin the decline of infection rates of C. sinensis, including replanting family farms to move farm animals from water sources and decreasing the consumption of raw fish in their diet.[3]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

While most C. Sinensis infections are asymptomatic with a parasite load of approximately 100, acute infections require a more detailed and rigorous management strategy with several medical teams on board. Patients with a heavy parasite load of approximately 20,000 are at a higher risk for chronic, long-term issues. Such risks include ascending cholangitis, cholangiocarcinoma, and hepatitis. Once it has become clear that a parasitic liver infection has developed, it is important that gastrointestinal (GI)/surgery, internal medicine, and infectious disease specialists have a clear line of communication to begin therapy as soon as possible. Specialty trained nurses in infection control and gastroenterology should be involved in providing patient and family education, monitoring patients, and providing status reports to the interprofessional team. Pharmacists evaluate the appropriateness of medications prescribed, assess for drug-drug interactions, and participate in education. It is also important to make an accurate diagnosis of which parasite is the culprit of the current disease as there are several types of different parasitic liver infections. Clear communication between all involved specialties is important to ensure that the patient and any close contacts are treated quickly and properly to avoid any severe consequences. [Level 5]