Cochlear Implants

- Article Author:

- Ryan Krogmann

- Article Editor:

- Yasir Al Khalili

- Updated:

- 7/31/2020 2:31:23 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Cochlear Implants CME

- PubMed Link:

- Cochlear Implants

Introduction

A cochlear implant (CI) is a medical device that uses electricity to stimulate the spiral ganglion cells of the auditory nerve to restore sensorineural hearing loss. The purpose of this device is to convert sound to an electrical signal and deliver this to the hearing nerve, which bypasses the damaged hearing apparatus. The challenge in cochlear implants is the appropriate selection of patients who will benefit from this technology; this is a newer technology in medicine and continues to evolve rapidly. These devices are surgically inserted by otolaryngologists who work closely with audiologists to make this device effective for patients. This device is arguably the most successful device to replace sensory deprivation. The FDA regulates its production in the United States.

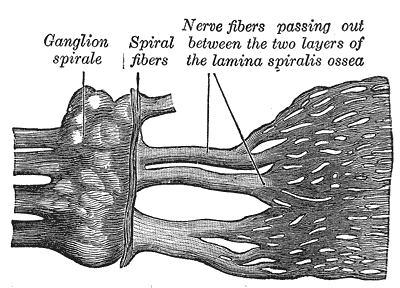

Anatomy and Physiology

The fundamental goal of a cochlear implant is to transmit sound from the external world to the cochlear nerve. The cochlear implant bypasses the external ear, the middle ear, and a portion of the inner ear. The cochlea is a spiral-shaped structure housed in the temporal bone. It has approximately 2.5 turns in a normal individual. There are three layers in a normal cochlea, including the scala tympani, scala media, and scala vestibuli.[1] The scala media houses the organ of Corti, which serves as the hearing organ that directly communicates with the cochlear nerve. The normal direction for sound to travel is from the external world, through the external ear canal, contact the tympanic membrane, transmit along the malleus, incus, and stapes and be directed through the oval window of the cochlea where the vibrational energy of sound travels along the scala vestibuli.[2] It reaches its peak at the helicotrema or the apex of the cochlea and the crosses over to the scala tympani, and this energy then gets emitted from the round window. The vibrational energy displaces the organ of Corti, causing stimulation of the cochlear nerve.

The cochlea has a tonotopical organization so that high pitched sounds locate along the base of the cochlea and low-frequency sounds organize around the apex. Placement of a cochlear implant is typically through the round window or a cochleostomy which will place the cochlear implant electrode in the scala tympani. Cranial nerve VIII (vestibulocochlear nerve) travels from the brainstem (pons) through the temporal bone and directly contacts the cochlea via fibers traversing through the modiolus. It runs in association with the facial nerve (cranial nerve VII). Relative to Bill's bar and vertical crest of the internal auditory canal, the cochlear nerve travels in the anterior inferior division.[3][4]

Indications

Candidates for cochlear implants are determined medically, by the FDA, and by insurance qualifications.

General indications[5]:

- Sensorineural hearing loss (prelingual or postlingual)

- Greater than 6 months of age

- Cochlear and cranial nerve VIII must be present with relatively preserved anatomy

- Bilateral or single-sided deafness

- Auditory neuropathy

- Reliability to follow up with audiology and otolaryngology team

- Able to undergo general anesthesia and surgical procedure

Insurance qualifications:

- Bilateral sensorineural hearing loss moderate to profound over 18 years of age (failed benefit from hearing aids)

- Bilateral sensorineural hearing loss severe to profound in patients from 2 to 18 years of age (failed benefit from alternative hearing amplification)

- Bilateral sensorineural hearing loss profound in children under 2 years of age (failed benefit from alternative hearing amplification)

- Minimum age of 12 months (younger if there is a concern for cochlear ossification which is a complication after meningitis)

- Adult open sentence scores with speech recognition less than 50% ear to be implanted, below 60 % in the contralateral ear (with amplification used)

- Pediatric Multisyllabic Lexical Neighborhood Test below 30% with a lack of auditory progress

- HINT Audiometric battery less than 50% in the implanted ear, less than 60% in the best-aided ear (scores depending on the manufacturer)

- MLNT audiometric battery less than 20 to 30 % (scores depending on the manufacturer)

- Hybrid system - (this device aids patients with high-frequency sensorineural hearing loss)

- Patients with profound high-frequency hearing loss and preserved low-frequency hearing thresholds range from 0 to 60 dB at 125 to 500 Hz

- A severe to profound middle- to high-frequency hearing loss as defined by a threshold average of greater than 75 dB at 2000, 3000, and 4000 Hz

- The consonant-nucleus-consonant word recognition score criteria are 10% to 60% in the ear to be implanted and up to 80% in the contralateral ear

- Reliability to follow up with otolaryngology and audiology to perform auditory rehabilitation

Contraindications

Cochlear implants are contraindicated in several patient populations. It merits mentioning that patients who meet criteria but wish to avoid surgery are not candidates. There are alternative forms of communication that require explanation, such as sign language. Patients born without a cochlea (cochlear aplasia) or cranial nerve VIII would not be candidates. Conversely, cochlear hypoplasia (a form of altered cochlear anatomy) is not a contraindication to cochlear implantation; such as a Mondini malformation (incomplete turns or partitions of the cochlea, a congenital defect). Patients who cannot tolerate general anesthesia are not candidates. Patients who have conductive hearing loss, unilateral sensorineural hearing loss, or hearing loss serviceable by hearing aids would all be better served by an alternative management plan that an otolaryngologist would be able to recommend. Cochlear implants do not fix all types of hearing loss. Thus it is imperative to have a thorough evaluation by an otolaryngologist in conjunction with an audiologist to ascertain the type and severity of hearing loss and then provide measures to correct the hearing loss.

Equipment

All cochlear implant systems have both external and internal hardware. The external equipment includes a microphone, a sound processor, and a transmission system. The internal device includes a receiver/stimulator and an electrode array.

In general, an external microphone picks up sound and/or speech in the environment and sends the information to a sound processor. The speech processor converts the mechanical vibration (sound) into an electric signal, which gets sent through the skin via radio frequency transmission to the internal receiver/stimulator. For successful transmission through the skin, the external magnet on the transmitter must align with the internal magnet on the receiver (stimulator). The receiver/stimulator takes the electrical signal and moves it to the electrode positioned within the cochlea. The electrodes provide stimulation to the auditory nerve, and the signal is sent along the auditory pathway to the auditory cortex in the brain. There are several manufacturers of cochlear implants in the United States, each with different specifications to customize the device to individual patient needs. A full review of all the different companies and models is beyond the scope of this article.

Companies: Each company has device specifications required for implantation and patient selection; please refer to these companies for device-specific details.

Personnel

An audiologist is a person who provides the audiometry test to determine the type and severity of the hearing loss. They also work closely with patients after cochlear implant insertion to provide therapy, which allows patients to receive maximum benefit from the device. They may also adjust the device to the patient's needs. Otolaryngologists are the medical physicians who provide the diagnosis of sensorineural hearing loss and determine which patients meet the criteria for cochlear implants. Otolaryngologists also perform the surgery of cochlear implantation. There are general otolaryngology physicians, otologists, and neurotologists who may perform this surgery. Otology and neurotology require an additional 1 to 2 years of training after completing an otolaryngology residency.[6]

Regularly scheduled follow-up is necessary for successful outcomes after cochlear implantation. The adult cochlear implant patient should have his or her external devices evaluated and programmed annually. Pediatric patients require evaluation at least twice yearly. Many children are seen more frequently than twice a year if any questions arise on how their listening skills are developing and to ensure that their devices are programmed appropriately.

Preparation

Preparation for cochlear implantation begins with a proper diagnosis of sensorineural hearing loss. History and physical exam will initiate the patient encounter. Special note to rule out secondary causes of hearing loss including tympanic membrane perforation, middle ear effusion/infection, or canal atresia. These would have to be corrected before the placement of a cochlear implant as they can affect the audiological findings that determine if patients are candidates for hearing aids. The next step is to obtain a basic audiogram with tympanometry. In children who are unable to respond appropriately to sound, an auditory brainstem response (ABR) will be necessary. The ABR is a test that transmits sound through the ear and determines if it reaches the cochlear nerve and secondary structures of the hearing apparatus by measuring the electrical potential that occurs from being stimulated. It is a useful test for both pediatric patients and to rule out hearing loss in patients who may be malingering. After there is confirmation that bilateral sensorineural hearing loss is present and meets the criteria for cochlear implantation, imaging is the next step. A solid history and physical exam may reveal findings that warrant further investigations, referrals to rule out coexisting abnormalities. In pediatric patients deemed to have profound sensorineural hearing loss evaluation by geneticists should be a consideration.[7]

Typically a CT of the temporal bones without contrast and MRI of the internal auditory canals with and without contrast is obtained, however one or the other would suffice.[8] These images determine the presence of the cochlear nerve; also, it gives important anatomic detail regarding surgical anatomy if inserting a cochlear implant.[4] Prior to placing a cochlear implant, a trial of hearing amplification should take place. In newborns, it is generally recommended to have hearing aids by the age of 6 months with a trial of 6 months before pursuing a cochlear implant. In adults, the period is shorter (1 to 3 months), and the benefit of hearing aids can be analyzed with a repeat audiometric battery. If patients have failed amplification measures and are candidates for hearing aids, then a discussion of the risks and benefits, as well as alternatives to the surgery should take place. After appropriate informed consent is obtained, a patient may schedule for surgery.[9] The CDC recommends vaccinations against Streptococcus pneumoniae including PCV13 and PPSV23 (for those over the age of two). PCV 13 is safe for children under the age of two years old; this has been shown to reduce the risk of meningitis associated with cochlear implants.[10]

In the United States, insurance companies do not always cover bilateral cochlear implants, causing difficulty for the cochlear implant team in determining which ear to place a cochlear implant. Generally, the ear with the shortest duration of deafness, the worse hearing ear, and the handedness of a patient for device manipulation may be factors to help determine appropriate implantation. If there are no audiometric differences between ears, then choose the better surgical ear. Some studies suggest that it may not matter which ear receives the implant (better or worse hearing ear), but the intervention of a cochlear implant will be of great benefit when the patients meet criteria.[11] Factors to consider are an ideal mastoid to drill, the side with the least ossification or fibrosis in the cochlea, and the side with normal anatomy.[12][13]

Technique

A cochlear implant takes place in an operating room at a hospital or surgical center. A team of nurses, anesthesiologists, and the otolaryngology team will see the patient on the day of surgery and discuss their role in the surgery. After addressing questions and concerns and obtaining consent, the patient will proceed to the operating theatre. The room will be sterile. A timeout will be performed to assure the proper patient and surgery. Anesthesia will then be initiated, typically a general anesthetic by endotracheal tube. Nerve monitoring is often used to monitor the facial nerve during surgery. The patient will undergo prepping in a sterile fashion, and sterile gowning and gloving takes place.

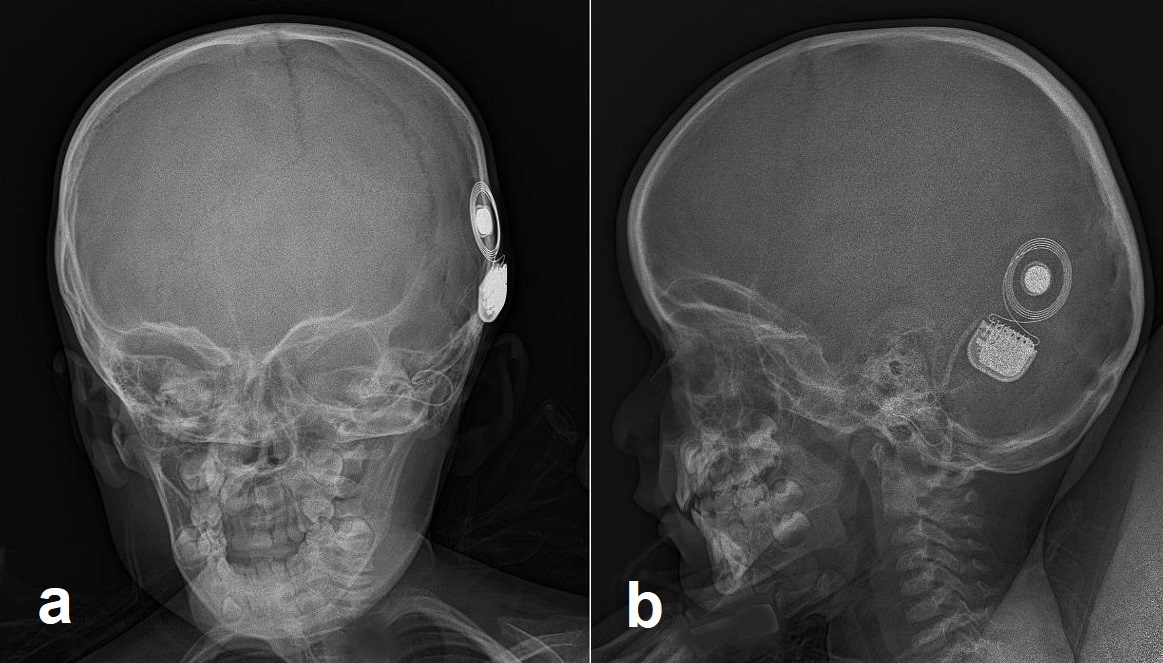

At this time, the surgery may commence. A standard mastoidectomy is performed with exposure of the facial recess using a mastoid drill per surgeon preference. The facial recess is an area bounded by the incudal bar, facial nerve (mastoid segment) and chorda tympani.[14] This area should provide adequate visualization of the round window of the cochlea. The operating surgeon may perform a cochleostomy if necessary. The processor is then slipped underneath the temporal fascia, or a bony well may be drilled to secure the device. The electrode is inserted after the opening of the round window or cochleostomy and inserted per manufacturer recommendations. At the time of implant, an audiologist or device representative should be present to test for proper device alignment within the cochlea. An X-ray is taken to confirm placement before the closure of the skin. Layered closure follows in a cosmetically pleasing fashion.[15]

Complications

Complications include [16][17]:

- Bleeding, including life-threatening bleeding

- Stroke

- Infection

- Increased risk for meningitis

- Pain

- Skin breakdown overlying the area of the magnet

- Device failure including broken portions of the device failed device or improper placement in the cochlea

- Skull base damage

- Trauma to the brain

- Cerebrospinal fluid leaks

- Facial nerve paralysis/paresis

- Loss of taste on the ipsilateral side of the tongue

- Death

- Dizziness/vertigo

- Loss of residual hearing in select populations

- Complete deafness

Clinical Significance

This device has given people once deemed deaf, the ability to hear once again, which is a profound medical accomplishment. All age ranges may benefit from this device, which impacts the patients differently at different stages of life. In the elderly population, patients with severe to profound sensorineural hearing loss have been shown to lead to dementia at an earlier age compared to peers. The social isolation associated with acquired hearing loss in elderly individuals, the significant decline in quality of life, and increases in emotional handicaps are risk factors leading to cognitive decline which show improvement with cochlear implants for appropriately selected patients.[18] Hearing aids have been shown to prevent progression to dementia and even reverse mild cognitive impairment.[19] Research suggests that cochlear implants may extend a patient's life, as dementia may lead to an earlier death compared to peers.

In prelingually deaf individuals (primarily children) the ability to develop speech is drastically improved, and they may not be required to learn alternative forms of communication such as sign language. Disclaimer, there is nothing wrong with patients who need or choose to use alternative forms of communication, and their communities should be respected, as this can aid in patient integration into regular classroom environments. Although educational costs for all implanted patients remain increased compared to children without hearing impairment, the ultimate achievement of educational independence for most implanted children produces net savings that range from $30000 to $100000 per child, including the costs associated with initial cochlear implantation and postoperative rehabilitation.[20] The ultimate goal is to perform bilateral cochlear implant insertion for children as this has been shown to improve learning in children and provides a more natural listening experience for a patient.[21] In summary, cochlear implants allow speech development, speech restoration (postlingually deaf), restoration of hearing (which has numerous implications from safely crossing the street in traffic and increased quality of life such as listening to music), integration into regular classroom settings, and the potential for increased earning potential. Hearing aids are customizable to an individual, and after successful implantation, the audiology team works with the patient to adjust implant settings to fulfill best the daily requirements a user may need. There is continuous growth in the research and technology regarding cochlear implants, which has provided more benefits for users as well as for cochlear implant teams in the selection and management of patients.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Cochlear implantation success is inherently dependent on a dedicated interprofessional team. The team may include pediatricians, family physicians, geneticists, otolaryngologists, otologists, neurotologists, audiologists, speech-language pathologists, school administrators, counselors, etc. All members serve different roles in patient care, which may be determined by the age of the patient, the age at diagnosis, and prelingual or postlingual deafness, to name a few of the variables. The goal of effective patient outcomes is to identify hearing loss as soon as possible with evaluation by an otolaryngologist and audiologist. Currently, 43 states in the USA have established newborn hearing screening programs (Early Hearing and Detection and Intervention). These programs have facilitated earlier diagnosis and management of congenital hearing loss. At this stage, the severity and best modality for treatment can commence without delay. In infants and children, this may facilitate evaluation by a geneticist who may determine the etiology of hearing impairment and associated abnormalities that require medical attention. In some scenarios such as an enlarged vestibular aqueduct, this thorough evaluation may prevent hearing loss, and allow for preventative measures. In adults, early recognition is beneficial to determine the etiology and provide appropriate management to enable patients to return work and reinstate their quality of life.[22] Hearing loss is a risk factor for injury, and it can decrease quality of life as well as prevent patients from performing their duties at work and earning an income.[23]

Once patients are candidates for cochlear implants, the otolaryngologist and audiologist team manage this portion of care. The otolaryngologist will perform the surgery to insert the cochlear implant. To maximum benefit from the device otolaryngology, audiology, speech-language pathologists, specialty-trained ENT nursing, and many other team members are then involved in the aftercare to make sure the device functions to its maximum potential and concerns are reported to the clinician managing the case. In prelingually deaf patients the goal is to develop speech and maximum communication. For postlingually deaf patients, the goal is to reinstate communication to a functional level. Communication between team members is essential in the identification, diagnosis, management, and continued surveillance of these individuals.[6]

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Monitoring

Nurses play a critical role in the healthcare team regarding cochlear implants. Whether a preoperative nurse, an intraoperative nurse or post-operative nurse, there are numerous tasks where nurses play a vital role. Preoperatively, nurses play a crucial role in prepping the patient for surgery. A basic review of the patient's history should be obtained in addition to vitals. If there are any red flags to surgery such as recent ear infections, concerns for an unstable patient (heart attack, stroke), change in medical history, or abnormal vitals, then the surgeon should be updated promptly. Patients must be healthy enough to withstand surgery for cochlear implants to be successful.

Intraoperatively, nurses help set up the patient and prepare the room with the necessary equipment. Every surgeon will have a different preference in how they approach cochlear implant surgery. Communication is key between the surgeon and the nursing staff. Having a general knowledge of otologic instruments can save the surgeon a lot of time and make the surgery more efficient, which is especially crucial for young children undergoing anesthesia. Nurses need to know the general steps of surgery and the necessary equipment to have ready for the surgeon.

Postoperatively, nurses will monitor patients. Appropriately attending to the patient's needs is imperative, in addition to gathering accurate vitals. It is essential to monitor the patient's alertness, change the mastoid dressing as instructed, and monitor for any bleeding or purulent drainage from the incision site, and to update the surgical team with any concerns. Typically, after a cochlear implant patient will have mild to moderate pain, experience dizziness, be sleepy from anesthesia (and possibly nauseation), and may have constipation due to pain medications. It is abnormal to have facial weakness, a sudden change in mental status, bleeding that soaks through a mastoid dressing, severe pain not controlled with opioids, or abnormal vitals. These concerns mandate updating the surgical team for evaluation.

The nursing staff is critical in successful cochlear implant surgery.

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)