Conjunctivitis

- Article Author:

- Eva Ryder

- Article Editor:

- Scarlet Benson

- Updated:

- 8/11/2020 11:34:12 AM

- For CME on this topic:

- Conjunctivitis CME

- PubMed Link:

- Conjunctivitis

Introduction

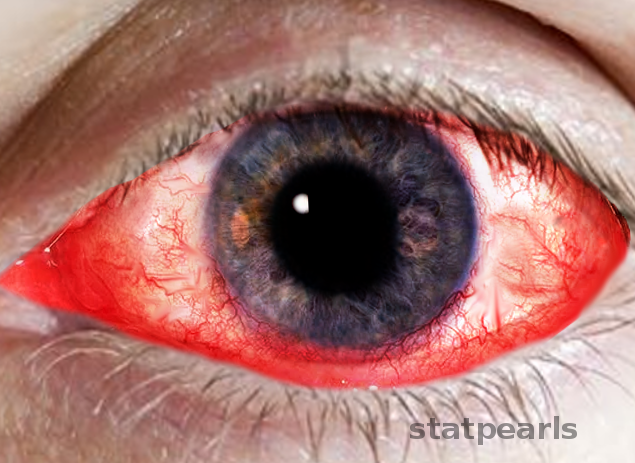

Conjunctivitis is a common cause of eye redness and subsequently a common complaint in the emergency department, urgent care, and primary care clinics. It can affect people of any age, demographic or socioeconomic status. Although usually self-limiting and rarely resulting in vision loss, when assessing for conjunctivitis, it is essential to rule out other sight-threatening causes of red-eye.

The conjunctiva is the transparent, lubricating mucous membrane covering the outer surface of the eye.[1] It is composed of two parts, the “bulbar conjunctiva” which covers the globe and the “tarsal conjunctiva” which lines the eyelid's inner surface.

Conjunctivitis refers to the inflammation or infection of the conjunctiva. It can be acute or chronic and infectious or non-infectious. Acute conjunctivitis refers to symptom duration 3 to 4 weeks from presentation (usually only lasting 1 to 2 weeks) whereas chronic is defined as lasting more than 4 weeks.

Etiology

Conjunctivitis is the most prevalent etiology of eye redness and discharge. While there are many types of conjunctivitis, viral, allergic and bacterial are the three most common.

Infectious conjunctivitis can result from bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites. However, 80% of acute cases of conjunctivitis are viral, the most common pathogen being Adenovirus. Adenoviruses are responsible for 65 to 90% of cases of viral conjunctivitis.[2] Other common viral pathogens are Herpes simplex, Herpes zoster, and Enterovirus.

Bacterial conjunctivitis is far more common in children than adults, and the pathogens responsible for bacterial conjunctivitis vary depending on the age group. Staphylococcal species, specifically Staphylococcal aureus, followed by Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae are the most common cause in adults, while in children the disease is more often caused by H. influenza, S. pneumoniae, and Moraxella catarrhalis.[2] Other bacterial causes include Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, and Corynebacterium diphtheria. N. gonorrhoeae is the most common cause of bacterial conjunctivitis in neonates.[1]

Allergens, toxins and local irritants are responsible for non-infectious conjunctivitis.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of conjunctivitis varies by age, sex and time of year. There is a bimodal distribution of diagnosed cases of acute conjunctivitis NOS in the ED. The highest rates of diagnosis are among children less than 7 years of age, with the highest incidence occurring between the ages of 0 and 4 years. The secondary peak of distribution occurs at the ages of 22 years in women and 28 years in men. Overall the rates of conjunctivitis diagnosed in the ED are slightly higher in women than in men. Seasonality is also a factor in the presentation and thus the diagnosis of conjunctivitis. Varying by age, there is a peak incidence in all presentations of conjunctivitis in children ages 0 to 4 years in March, followed by other age groups in May. A nationwide ED study found seasonality to be consistent for all geographic regions, regardless of changes in climate or weather patterns.[3] Allergic conjunctivitis is the most frequent cause of conjunctivitis, affecting 15 to 40% of the population, and is observed most commonly in spring and summer. Bacterial conjunctivitis rates are highest from December to April.[1][2][3]

Pathophysiology

Conjunctivitis results from inflammation of the conjunctiva. The cause of this inflammation can be due to infectious pathogens or non-infectious irritants. The result of this irritation or infection is injection or dilation of the conjunctival vessels; this results in the classic redness or hyperemia and edema of the conjunctiva. The entire conjunctiva is involved, and there is often discharge as well. The quality of discharge varies depending on the causative agent.

History and Physical

History and physical examination are, of course, essential in the diagnosis of conjunctivitis, and in determining the cause and therefore treatment of the condition.

Ocular history includes timing of onset, prodromal symptoms, unilateral or bilateral eye involvement, associated symptoms, previous treatment and response, past episodes, type of discharge, the presence of pain, itching, eyelid characteristics, periorbital involvement, vision changes, photophobia, and corneal opacity.

The ocular exam should focus on visual acuity, extraocular motility, visual fields, discharge type, shape, size and response of pupil, the presence of proptosis, corneal opacity, foreign body assessment, tonometry, and eyelid swelling.

The redness of the conjunctiva in conjunctivitis should be diffuse and involve the entire conjunctival surface, both the bulbar and tarsal conjunctiva, which helps exclude more severe conditions such as keratitis, iritis, and angle closure glaucoma as they will involve the entire bulbar conjunctiva but spare the tarsal conjunctiva. If the redness is localized, one should consider an alternative diagnosis of foreign body, pterygium or episcleritis.

After redness, the type of discharge is an important factor in determining the cause of conjunctivitis. Bacterial conjunctivitis is typically associated with purulent discharge which reforms immediately after removal from the eye, or mucopurulent discharge which tends to be thicker and sticks to the eyelashes. In comparison to other causes of bacterial conjunctivitis, N. gonorrhoea is typically hyperacute in presentation, presenting with copious purulent discharge, abrupt onset, and rapid progression. Traditionally, the discharge in both viral and allergic conjunctivitis is watery. In the context of watery discharge, the additional finding of preauricular lymphadenopathy can point one toward the diagnosis of viral, rather than allergic conjunctivitis.

Similar to redness and discharge, many other common signs and symptoms of conjunctivitis are nonspecific and can make determining the underlying cause more difficult. For example, the itching has historically correlated with allergic conjunctivitis, and while in the context of watery discharge and a history of atopy this is likely true, one study found that 58% of patients with culture-positive bacterial conjunctivitis also reported itchy eyes.

Comparably, papillae are a nonspecific finding in conjunctivitis. Papillae can be present in both noninfectious and infectious conjunctivitis. They are small elevations usually under the superior tarsal conjunctival, with central vessels. Papillae are often present in bacterial conjunctivitis, allergic conjunctivitis, and contact lens intolerance. The papillae in chronic allergic conjunctivitis can lead to a cobblestone appearance of the conjunctiva.

While also non-specific, the presence of follicles, in correlation with other findings, can help differentiate the etiology of conjunctivitis. Follicles are small elevated yellow-white lesions found at the junction of the palpebral and bulbar conjunctiva, also known as the lower cul-de-sac. Follicles are a lymphocytic response often present in chlamydial and adenoviral conjunctivitis.

In a patient with a history of perioral cold sores, current skin lesions or suspected viral conjunctivitis, a fluorescein examination should be performed as HSV can produce corneal dendritic lesions even in the absence of skin lesions. This exam is an important step in the physical evaluation as it may result in the only finding to differentiate HSV from other viral causes of conjunctivitis which subsequently requires different management and follow-up. In comparison, herpes zoster ophthalmicus typically presents in patients over 60 years with a painful vesicular rash following the distribution of the fifth cranial nerve. Prodrome can include headache, fever, malaise, and photophobia. Vesicles at the tip of the nose, referred to as Hutchinson’s sign, strongly predict eye involvement with HZ.

While presentations can often overlap, a systematic approach and thorough history and physical exam can safely rule out any acute sight-threatening diagnoses and lead you toward the likely cause of conjunctivitis. The classic findings of the three most common types of conjunctivitis can be found below[4][5][6][7]:

- Bacterial: symptoms of redness and foreign body sensation, morning matting of the eyes, white-yellow purulent or mucopurulent discharge, conjunctival papillae, infrequently preauricular lymphadenopathy.

- Viral: symptoms of itching and tearing, history of recent upper respiratory tract infection, watery discharge, inferior palpebral conjunctival follicles, tender preauricular lymphadenopathy.

- Allergic: symptoms of itching or burning, history of allergies/atopy, watery discharge, edematous eyelids, conjunctival papillae, no preauricular lymphadenopathy.

Evaluation

Labs and cultures are rarely indicated to confirm the diagnosis of conjunctivitis. Eyelid cultures and cytology are usually reserved for cases of recurrent conjunctivitis, those resistant to treatment, suspected gonococcal or chlamydial infection, suspected infectious neonatal conjunctivitis, and adults presenting with severe purulent discharge.[1][2][5] Rapid antigen testing is available for adenoviruses and can be used to confirm suspected viral causes of conjunctivitis to prevent unnecessary antibiotic use. One study comparing rapid antigen testing to PCR and viral culture and confirmatory immunofluorescent staining found rapid antigen testing to have a sensitivity of 89% and a specificity up to 94%.[8]

Treatment / Management

Treatment of both viral and bacterial conjunctivitis should include patient education to decrease the rate of transmission.

Bacterial conjunctivitis, while typically self-limiting, can be treated to help reduce the duration of symptoms. No significant difference in outcomes has been observed in trials comparing different types of ophthalmic antibiotic drops. While ointments typically last longer than drops, they tend to interfere with vision. Initial treatment for acute, non-severe bacterial conjunctivitis varies depending on the antimicrobial agent, but generally is administered to the affected eye from every two to every 6 hours for 5 to 7 days. Antibiotic options are available as liquid solutions and topical ointments. Liquid suspension/solutions include polymyxin b/trimethoprim, ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin, levofloxacin, moxifloxacin, gatifloxacin or azithromycin, while bacitracin, erythromycin or ciprofloxacin can be administered as an ointment. Fluoroquinolones should be prescribed for contact lens wearers to provide empiric coverage for Pseudomonas.

The recommended treatment for gonococcal conjunctivitis is ceftriaxone 1gm IM, and it is recommended to treat for concurrent chlamydial infection with 1gm azithromycin PO as well. The neonatal dosing for gonococcal conjunctivitis is 25 to 50mg/kg ceftriaxone IV/IM with a max dose of 125mg, with 20mg/kg azithromycin PO once daily for three days.

Viral conjunctivitis due to adenoviruses is self-limiting, and treatment should target symptomatic relief with cold compresses and artificial tears.

Herpes simplex keratitis should receive antiviral therapy. Mild infections can have treatment with trifluridine 1% drops every 2 hours or 8 to 9 times a day for 10 to 14 days, topical ganciclovir 0.15% gel 1 drop five times a day until epithelial heals and then three times daily for one week, or oral acyclovir 400mg PO 5 times a day for 7 to 10 days to limit epithelial toxicity. Patients should have a follow-up with ophthalmologists within 2 to 5 days to monitor for complications.

Treatment of herpes zoster conjunctivitis includes a combination of oral antivirals and topical steroids; however, steroids should only be part of therapy in consultation with ophthalmology. Antiviral doses differ from those used for herpes simplex and consist of oral acyclovir 800mg five times a day, oral famciclovir 500mg three times a day, or oral valacyclovir 1g three times a day, each for 7 to 10 days.

Topical corticosteroids are not recommended for cases of bacterial or viral conjunctivitis, except for herpes zoster, as they can prolong the disease or potentiate the infection, resulting in complications including corneal damage and blindness.

Lastly, the treatment for allergic conjunctivitis consists of allergen avoidance, artificial tears, cold compresses, and a wide range of topical agents. Topical agents include topical antihistamines alone or in combination with vasoconstrictors, topical mast cell inhibitors and topical glucocorticoids for refractory symptoms. Oral antihistamines can also be used in moderate to severe cases of allergic conjunctivitis.

Any patient with moderate to severe pain, vision loss, corneal involvement, severe purulent discharge, conjunctival scarring, recurrent episodes, lack of response to therapy, or herpes simplex keratitis should receive a prompt referral to an ophthalmologist. In addition, those requiring steroids, contact lens wearers, and patients with photophobia should also get a referral.[1][2][5]

Differential Diagnosis

There are many emergent and non-emergent causes of eye redness. When considering a diagnosis of conjunctivitis, it is essential to rule out the emergent causes of vision loss.

The differentials for conjunctivitis include:

- Glaucoma

- Iritis

- Keratitis

- Episcleritis

- Scleritis

- Pterygium

- Corneal ulcer

- Corneal abrasion

- Corneal foreign body

- Subconjunctival hemorrhage

- Blepharitis

- Hordeolum

- Chalazion

- Contact lens overwear

- Dry eye

Some signs and symptoms that point to diagnosis other than conjunctivitis include localized redness, redness that does not include the entire conjunctiva, ciliary flush, elevated intraocular pressure, vision loss, moderate to severe pain, hypopyon, hyphema, pupil asymmetry, decreased pupil response, and trouble opening the eye or keeping the eye open.

The clinician must not miss angle-closure glaucoma, iritis, infectious keratitis, corneal ulcer, foreign body, and scleritis, as they are sight-threatening and must have ophthalmologist management. Typically, the redness in keratitis, iritis and angle closure glaucoma will involve the entire bulbar conjunctiva but spare the tarsal conjunctiva. Additionally, patients presenting with glaucoma may have a semi-dilated pupil, corneal opacity, ciliary flush, and elevated intraocular pressure. In comparison, iritis also referred to as anterior uveitis, will commonly present with pain, blurred vision, photophobia, ciliary flush, and hypopyon. Hypopyon is a white or whitish-yellow collection of inflammatory cells in the anterior chamber. While hypopyon is commonly associated with iritis, it can be isolated or associated with other conditions such as infectious keratitis or a corneal ulcer.

In comparison to iritis, patients with infective keratitis will often complain of a foreign body sensation and trouble opening the eye or keeping the eye open. These findings are symptoms consistent with corneal involvement and can present with other corneal disorders such as corneal ulcer, abrasion or foreign body. Foreign body and orbital trauma can both result in hyphema, which refers to the collection of blood in the anterior chamber, which too can result in acute and permanent vision loss.

The final emergent condition not to miss is scleritis. Scleritis typically presents with severe pain radiating to the face that is worse in the morning and/or at night, associated with photophobia, pain with extraocular movement, tenderness to palpation and scleral edema. All patients with hypopyon, hyphema, suspected iritis, keratitis, scleritis, corneal ulcer or corneal foreign body should be evaluated by an ophthalmologist within 12 to 24 hours of presentation, while patients with suspected angle-closure glaucoma should see the ophthalmologist as soon as possible.

The remaining diagnoses are non-emergent. Pterygium and episcleritis are typically associated with localized redness, which differs from the diffuse redness seen in conjunctivitis. Blepharitis, contact overuse and dry eyes are similar in presentation to allergic conjunctivitis. All commonly present with a foreign body sensation, itching or burning. History of contact use, lack of blinking, and allergies/atopy are important in differentiating contact lens overwear, dry eyes, and allergic conjunctivitis, respectively. Crusting of the eyelids and marked erythema and edema of the eyelid margins are most consistent with blepharitis. Lastly, a subconjunctival hemorrhage is due to bleeding of conjunctival vessels and appears as blood in the subconjunctival space rather than the typical injection or vessel dilation seen in conjunctivitis.[5][9][10]

Prognosis

Conjunctivitis is easily treatable and usually benign and self-limiting. Symptom duration varies depending on the type. Viral conjunctivitis typically increases in severity until day 4 or 5 and resolves within the following 1 to 2 weeks for a total duration of 2 to 3 weeks. Bacterial conjunctivitis tends to last 7 to 10 days but can be shortened by early antibiotic administration within the first 6 days of onset.

Complications

Complications of acute conjunctivitis are rare. However, patients who fail to show improvement within 5 to 7 days should have a referral to an ophthalmologist for further evaluation. Patients with HZV conjunctivitis are at the highest risk of complications. Approximately 38.2% of patients with HZV develop corneal complications, and 19.1% develop uveitis; these patients should always see an ophthalmologist for close re-evaluation.[6] Patients with N. gonorrhea are also at high risk for corneal involvement and secondary corneal perforation and therefore should be treated appropriately.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Viral and bacterial conjunctivitis can spread by direct contact and have high transmission rates. Patient education is crucial to prevent transmission. The importance of hand hygiene for patients, staff, family, and friends should be highlighted. One study found that when swabbing the hands of infected patients, 46% resulted in positive cultures.[2] Patients should be instructed to avoid touching their eyes, shaking hands, sharing personal items such as cosmetics or towels and avoidance of swimming pools while infected. Medical instruments should be disinfected and admitted patients with active conjunctivitis should be isolated.[1][2][3]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Whether the initial diagnosis is made in the Emergency Department, Urgent Care, or Primary clinic, differentiating the type of conjunctivitis is critical in enhancing patient-centered care and outcomes. Depending on the setting of initial diagnosis, history and examination may be performed by a single individual or multiple. Therefore, it is essential for all team members including the ophthalmic nurse to have a clear and open line of communication. Specialty-trained nurses and pharmacists also figure into the interprofessional team approach to managing this condition. Efficacious communication will not only enhance team performance but will provide the best possibility for the correct diagnosis, and therefore the best opportunity at a successful outcome for the patient. Assessing for red flags and ruling out sight-threatening diagnoses are also critical in the interprofessional care of conjunctivitis. When necessary, prompt ophthalmologic consult and/or speedy referral for the high-risk disease should not be overlooked by providers. (Level V)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Follicular conjunctivitis may be seen with viral infections like herpes zoster, Epstein-Barr virus infection, infectious mononucleosis), chlamydial infections, and in reaction of topical medications and molluscum contagiosum. Follicular conjunctivitis has been described in patients with the Clovid-19 infection (coronavirus infection). The inferior and superior tarsal conjunctiva and the fornices show gray-white elevated swellings which are about 105 - 1 mm in diameter and have a velvety appearance

Contributed by Prof. BCK Patel MD, FRCS