Anatomy, Head and Neck, Cricoid Cartilage

- Article Author:

- Shibin Mathews

- Article Editor:

- Sameer Jain

- Updated:

- 8/10/2020 5:46:15 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Anatomy, Head and Neck, Cricoid Cartilage CME

- PubMed Link:

- Anatomy, Head and Neck, Cricoid Cartilage

Introduction

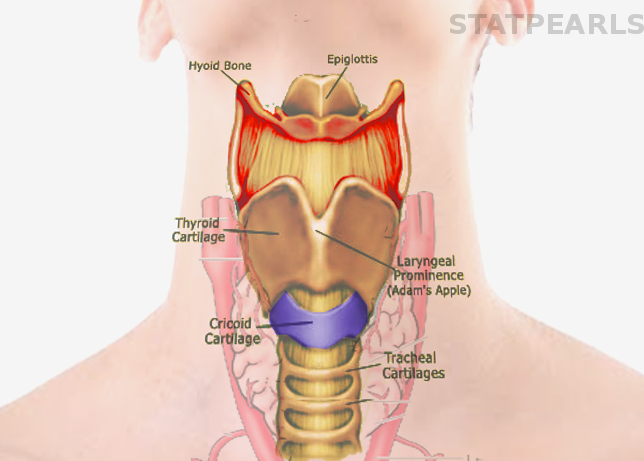

The cricoid cartilage is a hyaline cartilage ring which fully encircles the trachea and composes the inferior-most boundary of the laryngeal skeleton. The term “cricoid,” (Greek, krikos meaning “ring-shaped”) refers to the signet-ring resemblance of the cricoid cartilage. It has a narrow arch anteriorly, which widens into a broad lamina posterior to the airway. The cricoid cartilage serves to maintain airway patency, forms part of the larynx, and provides an attachment point for key muscles, ligaments, and cartilage, which function in the opening and closing the vocal cords for sound production.[1] Clinically, the cricoid cartilage is an important anatomical landmark for procedures such as cricothyroidotomy, used to establish a viable airway in an emergency setting.

Structure and Function

The unique structure of the cricoid cartilage is ideal for carrying out its functions: to contribute to the laryngeal structure and to provide an attachment point for key muscles of phonation. It is the sole cartilaginous full ring component and second largest cartilage of the laryngeal skeleton.[2] The cricoid cartilage is located inferiorly to the larger thyroid cartilage at the level of the C6 spinal vertebrae.[3] The superior border of the cricoid cartilage is linked contiguously to the thyroid cartilage anteriorly via the median cricothyroid ligament at the midline. The two lateral cricothyroid ligaments connect these structures on either side. The inferior border of the cricoid cartilage attaches to the first tracheal ring via the cricotracheal ligament.[1]

The composition of the cricoid cartilage is of hyaline cartilage, the body’s most abundant cartilage. It is found in the tracheal and laryngeal structures as well as the ribs and nose. Hyaline cartilage is semi-translucent, pale blue-white in appearance. It serves to reduce friction and provides durability to a structure. It also possesses the capability to withstand compressive forces at joint articulation sites. The structure of hyaline cartilage is relatively simple. It is avascular and aneural. As with all forms of cartilage, chondrocytes are sustained through diffusion of nutrients from its surrounding environment, facilitated by compressive forces acting on it. This metabolism is one of the reasons behind the slow regenerative capacity of cartilage. It is covered on the outside by a fibrous perichondrial membrane. The cartilage matrix is composed primarily of type II collagen and chondroitin sulfate (which increases elasticity and durability). As a person ages, the hyaline cartilage progresses from being soft and flexible to hard and more calcified. In the case of the cricoid cartilage, in rare cases, this can lead to possible surgical removal to clear the tracheal block created by calcification.[4]

In addition to contributing to the structure of the larynx and maintaining patency of the trachea, the cricoid cartilage serves as an important attachment point for several key laryngeal muscles, cartilages, and ligaments involved in phonation. Each half of the large posterior lamina of the cricoid cartilage contains two facets for articulation with other cartilages. The superolateral surfaces contain facets for articulation with the base of the arytenoid cartilages, via a ball and socket joint. This joint allows for the rotation of the arytenoids, within the facet, allowing abduction and adduction of the vocal cords aiding in phonation and airway protection. The other facets are located more laterally on the posterior lamina and provide facets for articulation for the medial aspect of the inferior horn of the thyroid cartilage. The cricoid cartilage serves as the attachment point for the following muscles: 1.) the lateral cricoarytenoid muscles 2.) the posterior cricoarytenoid muscles and 3.) the cricothyroid muscle.[5] These muscles will be discussed further in the corresponding section.

Embryology

Understanding the development of the cricoid cartilage necessitates first reviewing the formation of the larynx as a whole, as well as the other structures of the upper respiratory tract (bronchi and trachea). Development of these structures begins in the fourth week of development. The upper respiratory system begins as the laryngotracheal groove on the inferior aspect of the early pharynx. By the end of the fourth week, the laryngotracheal diverticulum has formed from the above-mentioned groove, and the successive development of the tracheoesophageal septum separates the primordial pharynx from the laryngotracheal tube. The laryngotracheal tube eventually gives rise to the larynx (as well as the bronchi and trachea).

The laryngeal epithelium forms from the endodermal layer at the cranial end of the laryngotracheal tube. The laryngeal cartilages, including the cricoid cartilage, are derived splanchnic mesenchymal condensations. The cricoid cartilage forms from these mesenchymal condensations (chondrification centers), forming in the infraglottic space. The cells in these centers, chondroblasts, secrete extracellular matrix and collagenous fibrils, which deposits in the intracellular matrix.[6]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The cricoid cartilage, like all other cartilage, is avascular and obtains its nutrients via diffusion from its surroundings. Due to the lack of blood supply, diffusion from surrounding tissues serves as the mode by which chondrocytes are nourished and remove waste. This exchange is facilitated by the movement and compressive forces acting on the cartilage.[4] The superior thyroid artery branches, which supply the larynx and the superior aspect of the thyroid gland, pass near the cricoid cartilage. The superior thyroid artery, a branch of the external carotid, supplies the cricothyroid muscle via the cricothyroid artery. Reidenbach (1997) describes the vasculature of the adjacent "cricoid area," which is the area bordered medially by the fibrous layer of the submucosa and the conus elasticus and laterally by the perichondrium of the cricoid cartilage. The cricoid area contains adipose and numerous blood vessels which pierce the lateral fibrous layer, providing a connection to adjacent laryngeal regions, resulting in the possibility for cancer to spread to the area.[7]

Nerves

The cricoid cartilage is aneural. The superior laryngeal nerve, of the vagus nerve (CN X), passes superiorly to the cricoid cartilage, innervating cricothyroid muscles. The superior laryngeal nerve divides into the external and internal superior laryngeal nerve. The external laryngeal nerve is susceptible to damage during a cricothyrotomy procedure.[5]

Muscles

The cricoid cartilage itself contains no muscles but serves as an essential attachment point for key laryngeal muscles involved in moving the vocal folds and producing sound. The superior aspect of the cricoid arch serves as the origin for the bilateral lateral cricoarytenoid muscles which run posterosuperiorly and inserts on the arytenoid cartilage. This muscle allows for internal rotation of the arytenoids, allowing for abduction and closing of the vocal folds. The posterior cricoarytenoid muscles run from the bilateral shallow depressions on the cricoid lamina and attach to the muscular process of the arytenoid. They serve to externally rotate the arytenoid cartilages and causing opening of the vocal cords. The final muscle with attachment to the cricoid cartilage is the cricothyroid muscle, which originates from the anterior and lateral aspects of the cricoid and attaches to the inferior horn of the thyroid cartilage. Its function is to tense and elongate the vocal cords causing higher pitch phonation.[8]

Physiologic Variants

There are well-documented studies of individual variations in cricoid cartilage dimensions, as it has important clinical implications in placements of stents, transplantation, endotracheal tubes and for surgical procedures. In a Swedish study by Randestad et al., laryngeal dimensions were taken from 34 men and 27 women, demonstrating the dimensional differences of the inner cricoid ring. In women, the mean diameter was 11.6 mm (range: 8.9 to 17.0 mm), and in men, the mean diameter was 15.0 mm (range: 11.0 to 21.5mm). There were differences noted amongst countries as well. A series from Germany showed similarities, but studies from India and Nigeria showed large variations in the mean and standard deviations of inner cricoid dimensions. The minimum diameter measured in the German study was 6.6 mm and was 8.0 mm in the Indian series. This finding is clinically relevant because it demonstrates that standard size tracheal tubes (9.5 to 10.0 mm for women and 10.5 to 11.0 mm for men) may not be inserted without causing mucosal damage in patients with small cricoid diameters. The variation in cricoid cartilage dimensions was not shown to correlate with body weight or height.[9]

Garbelotti et al. reported a structural variation in the cricoid cartilage. The cricoid cartilage described had a superior and inferior arch, with a fibrous membrane between them. While there have been few other documented cases of such variants, this difference can have clinical implications during a cricothyrotomy in certain individuals.[1]

Fayoux et al., examined cases of congenital laryngeal atresia, in which the cricoid cartilage was involved in all cases. Severe abnormalities were noted in individual cricoid cartilages including a median crest on the cranial edge, associated with anterior or posterior enlargements of the caudal edge, and persistence of the pharyngeotracheal duct.[10]

Surgical Considerations

Cricothyrotomy

Cricothyrotomy (or cricothyroidotomy) refers to the surgical procedure in which an incision is made in the skin and the cricothyroid membrane to establish an airway in emergency (life or death) situations in which there is airway blockage, such as oral or maxillofacial trauma, angioedema, or physical or anatomical blockages.[11] The cricothyroid membrane is identifiable by first palpating the large thyroid cartilage (“Adam’s apple”) and by inferiorly palpating the anterior portion of the signet-ring cricoid cartilage. The cricothyroid membrane is located approximately superior to the cricoid cartilage and 2 cm inferior to the thyroid cartilage and is palpable as the “dip” between these two structures. Following identification of the cricothyroid membrane, and proper stabilization of surrounding structures, a 4 cm vertical incision is made on the outer skin, followed by horizontal incision of the cricothyroid membrane. An endotracheal tube is then inserted, secured, and attached to a bag valve mask (BVM) or ventilator as a temporary measure until a more stable airway is established. Proper identification of the cricoid cartilage and the thyroid cartilage is essential to perform this procedure in an emergency setting successfully.[12]

Cricoidectomy

Cricoidectomy is a surgical procedure with partial or total excision of the cricoid cartilage. Cricoidectomy may be indicated in cases of subglottic stenosis, as the cricoid is the narrowest part of the airway[13] Cricoidectomy has also been considered an option in surgical resection of laryngeal chondrosarcomas, the vast majority of which originate from the cricoid cartilage. However, the role of the cricoid cartilage in providing structural support for the larynx as well as its role as a key attachment point for the arytenoid muscles is an important consideration for total cricoidectomy. In a series conducted by, De Vincentiis et al., only one patient out of three was successfully decannulated after a total cricoidectomy; this is primarily due to the instability of the posterior wall of the reconstructed airway, which composed by the membranous wall of the trachea. This new membranous wall provides insufficient stability to the lumen and inadequate support to the arytenoid cartilages.[14]

Clinical Significance

Sellick Maneuver

The Sellick maneuver is a technique by which pressure is applied directly to the cricoid cartilage during rapid sequence intubation (RSI), to prevent pulmonary aspiration. Pressure applied to the cricoid cartilage occludes the esophagus, which lies posterior to the cricoid. However, the use of the Sellick maneuver remains controversial.[15] In a recent large RCT by Birenbaum et al., it was hypothesized that a sham procedure would be non-inferior to the Sellick maneuver. However, the trial failed to demonstrate the noninferiority of the sham procedure with regards to this primary outcome.[16]