Congenital Pulmonary Airway Malformation

- Article Author:

- Pooja Mehta

- Article Editor:

- Girish Sharma

- Updated:

- 8/10/2020 4:20:27 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Congenital Pulmonary Airway Malformation CME

- PubMed Link:

- Congenital Pulmonary Airway Malformation

Introduction

Congenital pulmonary airway malformation (CPAM), one of the congenital lung diseases discussed under the umbrella term ‘congenital thoracic malformations,’ others being a bronchogenic cyst and pulmonary sequestration, is rare, but the most common developmental congenital anomaly of the lung. The malformation is due to abnormalities during embryogenesis and can occur at different stages during lung development, leading to anomalous bronchial morphogenesis. With new advancements and technological progress, CPAM is frequently diagnosed antenatally, and managed by a pediatric surgeon from early on. Infants with this diagnosis can present in a wide range of severity from being asymptomatic until later in life, to having respiratory distress while in the neonatal period.[1]

Etiology

Congenital pulmonary airway malformation results from the cessation of lung development during various stages of embryogenesis. There are a variety of genes implicated in this process including thyroid transcription factor gene (Nkx2), sex-determining region Y- box 2 gene (Sox2), Hox gene (Hoxb-5), Ying Yang 1 gene (Yy1), fatty acid-binding protein-7 gene (FABP-7), acyl-CoA synthetase 5 (ACSL5) platelet-derived growth factor B gene (PDGF-B), sonic hedgehog (SHH), bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4), sprouty 2 (SPRY2), Wnt signaling pathways, transforming growth factor B (TGFB), and fibroblast growth factors 10, 9, and 7 (FGF10, 9, 7). All of these genes have a role in cell proliferation or apoptosis, leading to the various types of malformations under the CPAM classification.[1][2][3]

Epidemiology

Though uncommon overall, about 95% of congenital cystic lung disease is accounted for by congenital pulmonary airway malformation. The incidence of CPAM is reported as 1 in 10000 to 1 in 35000 births. There have been some studies that show male predominance in lesions that present in early infancy. Overall, these malformations occur sporadically with no genetic predisposition (except Type 4), and no association with maternal factors.[4][5]

Pathophysiology

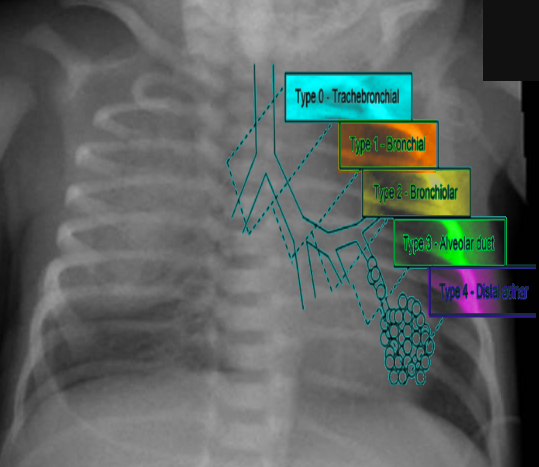

Congenital pulmonary airway malformation has five major subtypes that have been described and assigned by the Stocker classification. Each type originates from a different part of the bronchial tree, subsequently leading to distinct histopathological differentiation, clinical features, malignant potential, and prognosis.

Type 0 originates in the trachea or bronchi with histology showing bronchial type airways with cartilage, smooth muscles, and glands separated by mesenchyme. This type is incompatible with life.

Type 1 originates in the bronchi and accounts for about 70% of all CPAM. The cysts in this type are usually multiloculated, located within one lobe, and have a lining of pseudo-stratified columnar epithelium. There is also cell hyperplasia in about half the cases. This type has excellent prognosis following resection and rarely undergoes malignant transformation, however rarely, is shown to transform to broncho-alveolar carcinoma.

Type 2 originates in the bronchiolar regions and is the second most frequent type. This type is often associated with other types of anomalies (renal agenesis, cardiovascular defects, diaphragmatic hernia, skeletal defects, esophageal atresia). Usually, it presents as multiple small cysts with no mass effect. The prognosis is good and has no malignant potential.

Type 3 also originates in the bronchiolar regions but is less common than the previous types. This type typically involves and expands an entire lobe, and compresses the other lobes. These lesions are usually solid versus cystic. The prognosis is good with no malignant potential; however, there is typically an absence of pulmonary arteries within the lesion.

Lastly, Type 4 originates in the acinar structures of the lung. This type is very rare and consists of peripheral thin-walled cysts that are multiloculated, lined by alveolar type 1 or type 2 cells. There is a strong association of this type of CPAM with type 1 pleuropulmonary blastomas.[1][6]

History and Physical

In terms of the presentation of congenital pulmonary airway malformation, there is wide variability. Children can be symptomatic at birth or go through their entire infancy into childhood without exhibiting symptoms. With the advent of prenatal ultrasonography to diagnose CPAM, there has been an increase in the number of prenatal diagnoses, leading to an overall decrease in the percentage of symptomatic CPAM. Asymptomatic newborns have the potential for complications during childhood, such as respiratory infection or malignancy. Symptomatic newborns present with respiratory distress, with severity increasing with size due to compression of the adjacent airways. The various types of CPAM present with specific clinical features.

Type 0 is incompatible with life due to almost no gas exchange occurring.

Type 1 presents with increased respiratory effort, tachypnea, and cyanosis.

Type 2 presents similarly with respiratory distress, and also with other congenital anomalies (renal agenesis, cardiovascular defects, diaphragmatic hernia).

Type 3 lesions can expand the entire lung and can lead to fetal hydrops from pulmonary hypoplasia.

Type 4 CPAMs can often present as pneumothorax, and are often similar in presentation to Type 1. There is also a small risk of infection, malignancy, air leak, or bleeding.[7][8]

Evaluation

Congenital pulmonary airway malformation can be diagnosed prenatally and is the most common prenatally diagnosed lung malformation. The diagnostic modality used is fetal ultrasound and can classify as either microcystic or macrocystic based on the size. If further differentiation of the lesion is needed, MRI is used, especially to distinguish between bronchopulmonary sequestration or congenital diaphragmatic hernia. If there is a prenatal diagnosis of CPAM, a chest radiograph should take place after birth. CPAM is most often diagnosed in the second trimester when diagnosed prenatally. If the infant has a diagnosis of CPAM from prenatal ultrasound and is symptomatic after birth, CT or MRI should be done to define the lesion. For asymptomatic infants, if the chest radiograph shows large lesions, bilateral or multifocal cysts, or a pneumothorax, then CT or MRI is recommended immediately. If asymptomatic without these characteristics, then CT or MRI should be done by six months of age. Even if chest radiography is normal, CT or MRI should be done, especially in asymptomatic infants. CPAM types 1 and 4 appear as one or two large air-filled cysts. Type 2 appears as multiple smaller air-filled cysts, giving a “bubbly” appearance on a chest X-ray. Type 3 presents as a solid, homogenous mass on chest X-ray, with a mass effect on the mediastinum.[4][9]

Treatment / Management

When diagnosed prenatally, congenital pulmonary airway malformation can be managed before delivery if there is a risk for fetal hydrops. If the clinician identifies this risk in the prenatal period, interventions such as fetal surgery, corticosteroids, or drainage can be done to prevent fetal demise. In the postnatal period, if the infant is symptomatic with respiratory distress, then surgical resection is the management of choice. Additionally, surgical resection is the recommendation for an infant with a lesion occupying more than twenty percent of the hemithorax, bilateral or multifocal cysts, pneumothorax (in context of CPAM), or a family history of pleuropulmonary blastoma. Often in older children with minor symptoms, resection is done as well to prevent recurrent infections or the potential for malignancy, especially if it is a known Type 4 lesion. For asymptomatic patients, there is a debate about whether the patient should have the lesion electively resected versus taking the conservative approach and observing for symptoms. Either option is viable, and the decision can be made at the discretion of the provider as well as discussion with the family about the advantages and disadvantages of each approach.[9][10][11]

Differential Diagnosis

The primary differential diagnosis, when considering congenital pulmonary airway malformation, is bronchopulmonary sequestration (BPS). BPS can also be present on prenatal ultrasound and usually appears as a well-defined, solid, and homogenous mass. The main difference between BPS and CPAM is that BPS has no connection to the tracheobronchial tree and receives its blood supply from the systemic circulation via an anomalous systemic artery rather than the pulmonary circulation, as in CPAM. Other diagnoses to consider when diagnosing CPAM are a congenital diaphragmatic hernia, bronchogenic cyst, congenital lobar emphysema, and pneumatoceles.[12]

Prognosis

The overall prognosis for congenital pulmonary airway malformation, when diagnosed prenatally, is excellent. There have been several cases that report prenatal regression of the lesion. If fetal hydrops is present, the survival rate drops. Surgical resection has been shown to increase survival rates and has proved to be curative in the neonatal period. There have been studies, however, that show conservative management, in selected cases, to be equally effective.[11] Out of the different types per the Stocker classification, Type 1 is shown to have the best prognosis. Type 2’s prognosis depends on the severity of the associated anomalies. Type 3 often has hypoplasia of an entire lobe leading to complications such as pulmonary hypertension. Type 4 has an excellent prognosis with surgical resection but does have a strong correlation with pleuropulmonary blastoma.[13]

Complications

Infection is the most common known complication of congenital pulmonary airway malformation and usually occurs in the first few years of the lives of asymptomatic infants, especially if surgical resection does not take place. The most commonly known malignant complication associated with CPAM is pleuropulmonary blastoma (PPB). The risk factors for developing PPB include having type 4 CPAM, having multifocal or bilateral cystic lesions, having a family history of PPB, and having a pneumothorax. An association exists between CPAM type 1 and bronchoalveolar carcinoma. There is also a risk of pulmonary hypoplasia leading to subsequent pulmonary hypertension, with type 3 CPAM as the lesion can occupy an entire lobe or entire lung.[14][15]

Deterrence and Patient Education

It is essential for patients and the parents of infants diagnosed with congenital pulmonary airway malformation to understand the prognosis, natural history, and various complications of the disease. Because of the ability to diagnose prenatally, the education may begin early on and therefore prepare the families in advance for the course of management. Having a multidisciplinary approach to the care of the infant will help offer the families a seamless transition from prenatal to postnatal care.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Congenital pulmonary airway malformation is a diagnosis that should be managed and monitored from the prenatal period and beyond, regardless of the severity of symptoms. Communication and coordination of care are imperative between the maternal-fetal health physician, obstetrician, pediatrician, and surgical team, especially if diagnosed prenatally. It is also vital to consider respiratory distress in a newborn as the initial presenting sign of CPAM, whether it is in the newborn nursery or NICU setting. If an infant is asymptomatic with a known lesion, and the decision is made to observe the infant versus resect surgically, then the recommendation is to have close follow up during the first year of life to monitor for any respiratory symptoms. Annual imaging with either chest radiograph or advanced thoracic imaging (either CT or MRI) is also necessary.[16] [Level 3]

Neonatal nursing is an integral strategic partner on the interprofessional healthcare team, collaborating with obstetricians and neonatal clinical specialists in the diagnosis and management of CPAM. They provide ongoing monitoring of the infant both before, during, and after procedures. For those patients who do not manifest symptoms until later in childhood, nursing at the pediatrician can fill a similar role. In all cases, the nurses can counsel the parents and educate them regarding the treatment and prognosis, reiterating the clinician's instructions. By operating as an interprofessional team, children with CPAM can achieve better outcomes. [Level 5]

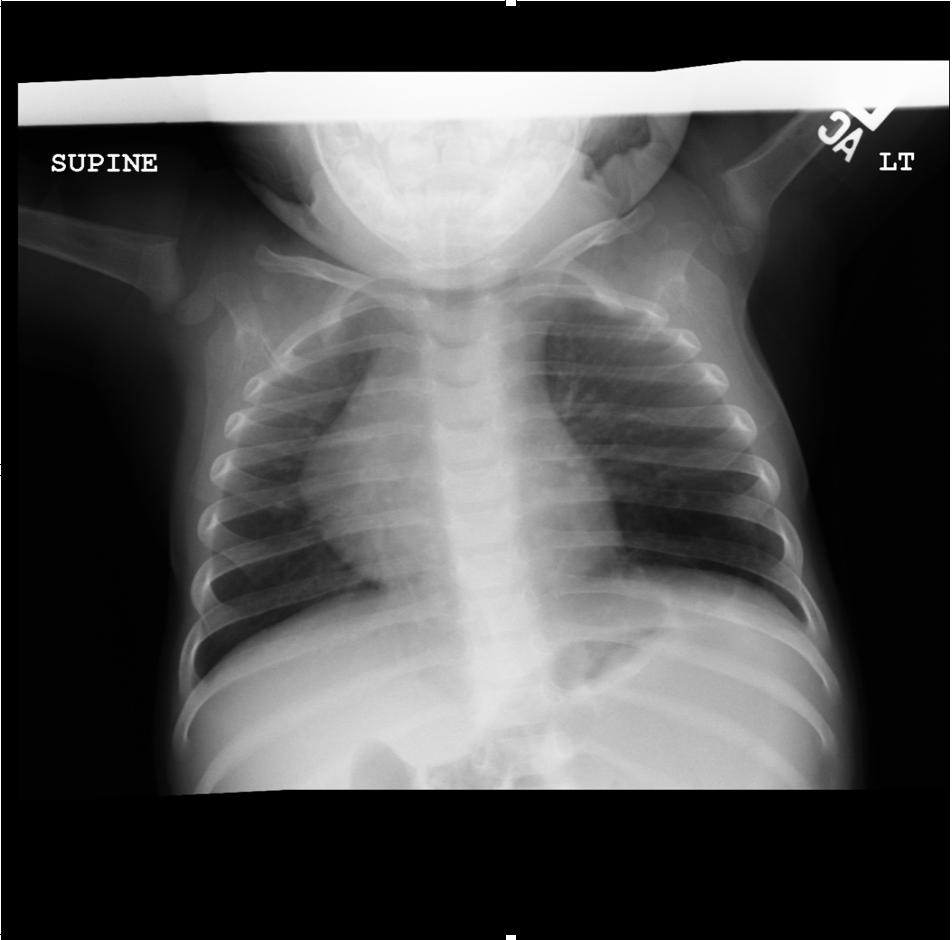

(Click Image to Enlarge)

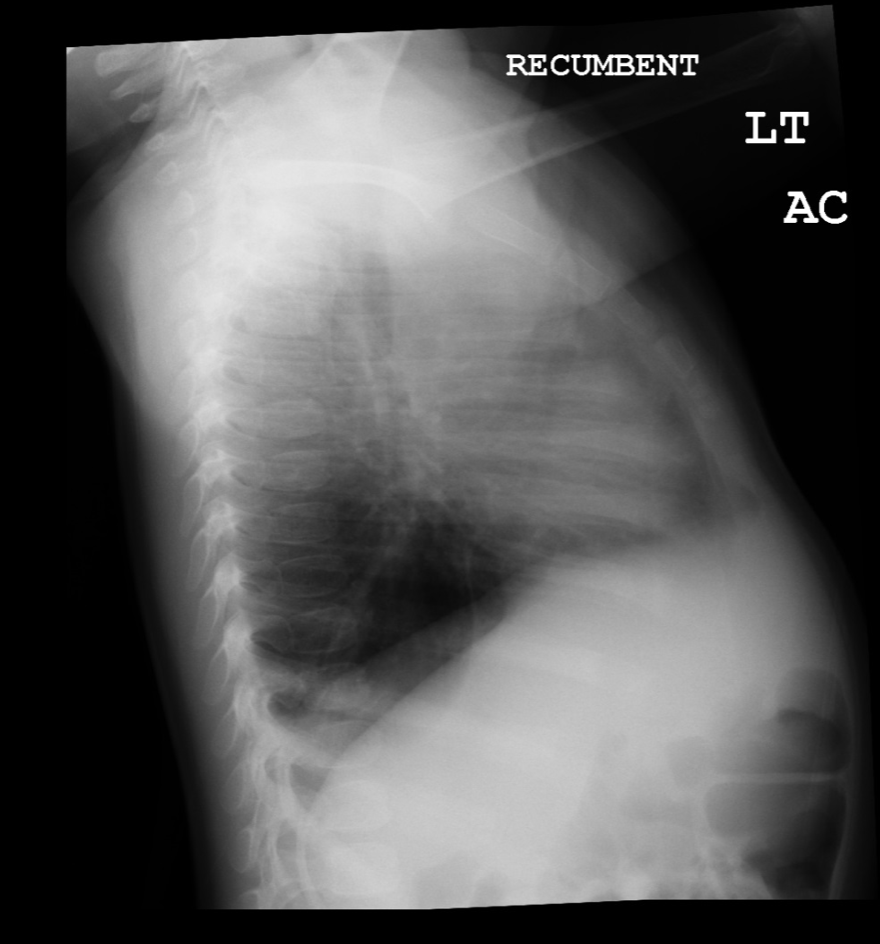

(Click Image to Enlarge)

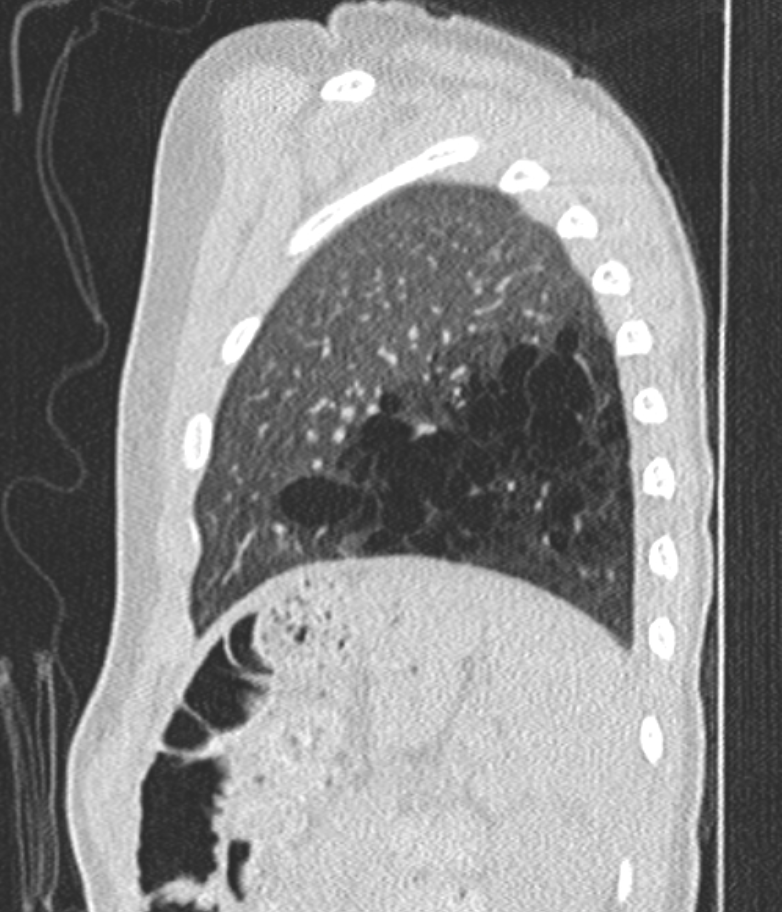

(Click Image to Enlarge)

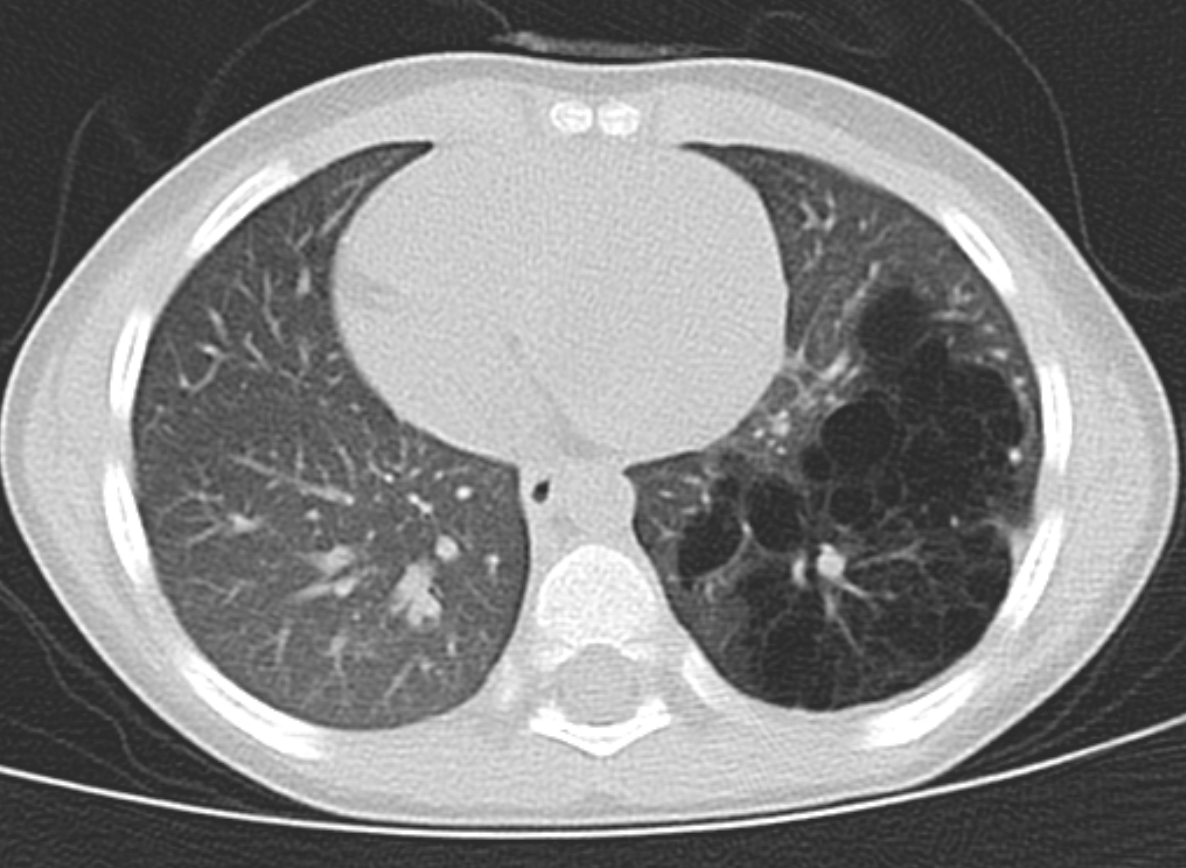

(Click Image to Enlarge)