Cystic Kidney Disease

- Article Author:

- Suleyman Goksu

- Article Editor:

- Divya Khattar

- Updated:

- 8/10/2020 5:21:36 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Cystic Kidney Disease CME

- PubMed Link:

- Cystic Kidney Disease

Introduction

Renal cysts are clinically insignificant or may cause end-stage renal failure and develops due to genetic or non-genetic causes in children and adults. Cystic kidney diseases can be part of multisystemic disorders with extrarenal symptoms. The most common cystic kidney disease in adults is autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. The cystic kidney is a disease diagnosed by renal size and cyst localization, as well as extrarenal symptoms.[1][2] Although many of these patients become symptomatic in childhood and adolescence, many patients remain undiagnosed. Therefore, the patients and their families need to receive adequate counseling to understand various rare cystic kidney syndromes.[1]

Etiology

Cystic kidney diseases (CKD) have several etiologies: developmental, inherited, acquired, and systemic disease-related. Inherited CKDs involve autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), which is one of the most common cystic kidney diseases caused by PKD1 and PKD2 mutations and autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD) caused by PKHD1 mutations.[3] The primary cause of ADPKD is interstitial inflammation and fibrosis. Another associated disease is glomerulocystic kidney disease (GCKD), which is an autosomal dominant (AD) disease and has an unknown genetic etiology. Medullary cystic kidney disease (MCKD) is an AD disorder due to MCKD1 and MCKD2 mutations, and juvenile nephronophthisis (JNPHP) is an autosomal recessive (AR) condition caused by NPHP1-NPHP5 genes.[4][5][6]

Developmental cystic kidney disease is caused due to abnormal development of the metanephros leading to a multicystic dysplastic kidney, with reduced nephron induction.[7]

Another cause of renal cysts is related to systemic diseases such as tuberous sclerosis (TS) and von Hippel Lindau (VHL) syndrome, which are autosomal dominant conditions with variable penetrance. Acquired cystic kidney disease develops secondary to obstruction of the tubules by fibrosis or oxalate crystals.[8]

Unilateral cystic kidney disease is a rare disease characterized by multiple cysts and is similar to ADPKD in both imaging and pathological examinations.[9]

Epidemiology

The incidence of ADPKD is 1/500 to 1000 persons, which affects 12.5 million worldwide, and mostly in adults.[6] End-stage renal disease (ESRD) is one of the significant complications of ADPKD, and symptomatic progression is seen mostly in men. ADPKD affects all racial and ethnic groups.

The incidence of ARPKD is 1 in 6,000 to 55,000 newborns. ARPKD is mostly diagnosed in infancy, childhood, or adolescence. ARPKD is the cause of 5% of ESRD in children.

The incidence of juvenile nephronophthisis (JNPHP) is 1 in 5,000 persons. 10% to 20% of children with JNPHP present with chronic renal failure and 1% to 5% of all patients need dialysis or transplantation. Additionally, JNPHP is the most common reason for genetic ESRD in children.[10][11]

The incidence of tuberous sclerosis (TS) is 1 in 10,000 to 50,000 persons, and 20% to 25% of these patients have renal cysts.[11]

Pathophysiology

Kidney cysts develop from renal tubule segments and detach from the parent tubule after growing a few millimeters. Development of cyst increases proliferation of the tubular epithelium, abnormalities in tubular cilia, and excessive fluid secretion. ADPKD develops due to mutations in the genes PKD1 and PKD2. ARPKD develops due to variations in PKHD1, which plays a critical role in collecting-tubule and biliary development.[1]

Histopathology

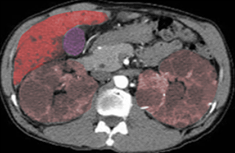

The nephron of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease has cystic dilatations with loss of tubule connection microscopically, and the kidneys in ADPKD are enlarged and distorted with multiple renal cysts.[12]

The microscopic evaluation of autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease shows fusiform dilation of collecting tubules, and the kidneys in ARPKD are also enlarged, but the shape of the kidney is preserved.

History and Physical

Cystic kidney diseases may present with different clinical signs and symptoms.

ADPKD usually presents with flank pain, intermittent hematuria, cyst hemorrhage, renal infection, nephrolithiasis, hypertension, and chronic renal failure. Also, ADPKD has several extrarenal findings; hepatic cysts are the most common ones, then followed by hepatomegaly, cardiac valve disease, diverticulosis, cerebral aneurysms, pancreatic cysts, and seminal vesicle cysts.[13]

In ARPKD, there are also renal and extrarenal presentations such as hypertension, renal insufficiency, palpable bilateral flank masses, electrolyte abnormalities (usually hyponatremia), and growth retardation. Pulmonary hypoplasia is a severe extrarenal finding and may cause neonatal death. ARPKD is generally associated with hepatic disease, including portal hypertension, varices, and splenomegaly.

Glomerulocystic kidney disease presents with hypertension, abdominal masses, and renal failure in neonates; flank pain, hematuria, and hypertension in adults.

JNPHP presents with growth retardation, polyuria and polydipsia, skeletal dysplasia, anemia, and progressive renal failure.

Tuberous sclerosis has several other findings, including angiofibromas, facial nevi, cardiac rhabdomyomas, epilepsy, and mental retardation.

VHLS is a cystic disease of the pancreas, kidneys, and epididymis, and develops renal cell carcinoma, retinal and cerebellar hemangioblastomas, pheochromocytomas.[14]

The acquired renal cystic disease usually progresses without any symptom; however, it can present with palpable renal mass, gross hematuria, flank pain, and renal colic.

Evaluation

There are several different ways to evaluate for cystic kidney disease due to various types of presentations.

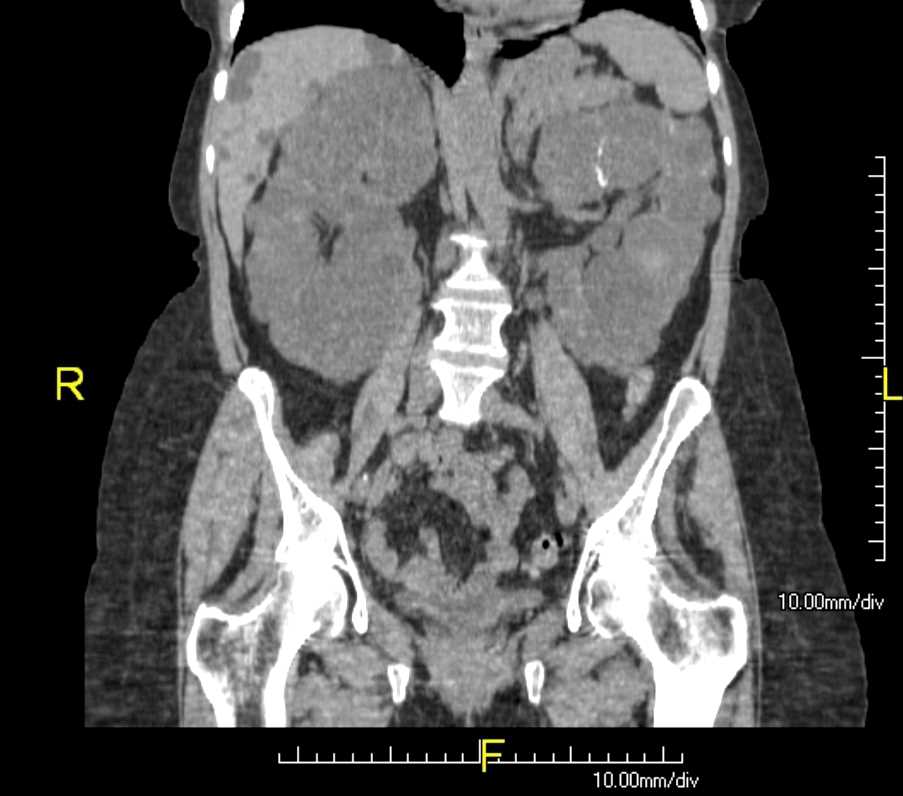

The diagnosis of ADPKD is clinical; however, genetic analysis and sonography can be used for early detection for patients who are asymptomatic but have a family history.[15] Sonography is the standard and cost-effective imaging method, but CT and MRI are more prognostic methods.[16]

ARPKD is diagnosed with genetic testing and sonography. Serum sodium concentration can be used for evaluating hyponatremia; urine osmolality for displaying reduced concentrating ability. Also, bilirubin and hepatic enzyme, complete blood cell counts (CBCs), can be performed for the risk of portal hypertension and splenic dysfunction.

JNPHP and MCKD are diagnosed with increased serum sodium concentration, minimal proteinuria, normal sediment. Sonography and CT scan can show shrunken kidneys.

Another helpful tool is the Bosniak classification, which helps to diagnose and manage cystic lesions with pre- and post-contrast CT scanning.[17] It has four categorizations for evaluating cysts in kidneys.

- Category 1 shows benign simple cyst with a thin wall without septa, calcifications, or solid components, and do not require further evaluation.

- Category 2 shows a benign simple cyst with a few thin walls and septa with fine calcifications. Follow-up in selected patients to confirm the diagnosis 6 to 12 months later.

- Category 2F is indeterminate between category 2 and 3; and has multiple thin septa, minimal smooth thickening wall with nodular calcification — follow-up with imaging.

- Category 3 that 40% to 60% are malignant, a multilocular lesion with thickened walls or septa, irregular calcifications — follow-up with periodic imaging, needle biopsy, or surgery.

- Category 4 that 85% to 100% are malignant, large nodular lesions with enhancing solid components, and requires surgery.

Treatment / Management

Cystic kidney disease includes several treatable and preventable complications such as hypertension, infection, and pain.

In ADPKD, recommendations include drinking 1 to 2 L of water daily, sodium restriction, exercise, and weight control. Hypertension is a common finding, and there are several options to control hypertension, including angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), calcium channel blockers. Tolvaptan is a vasopressin receptor antagonist that is effective for ADPKD with selective candidates.[18] Cyst infections can develop in ADPKD, which can be treated with a course of antibiotics such as ciprofloxacin, erythromycin, chloramphenicol, or a tetracycline. Renal cysts are generally asymptomatic, but if it is symptomatic, needle aspiration can be needed. Moreover, laparoscopic techniques can be performed for complex cysts.[19]

ARPKD has no curative treatments; therefore, there is only symptomatic management, including supportive respiratory therapy for pulmonary insufficiency, dialysis for renal failure, salt restriction, and usage of antihypertensives for hypertension, and loop diuretics for edema.[20]

JNPHP and MCKD are managed with salt supplementation when there is severe salt wasting, and dialysis or renal transplantation for ESRD if needed.

Acquired cystic renal disease patients need bed rest and analgesics for mild bleeding episodes of cysts. Hypercalciuria can be treated with oral thiazide diuretics when it occurs in this disease.

Differential Diagnosis

Some diseases which may have renal cysts and similar presentations include multilocular cystic nephroma, hemangioma, angiomyolipomas, and renal cell carcinoma. A complete history and physical exam for secondary findings along with imaging modalities and genetic testing can help differentiate the etiology of the renal cysts.

- Angiomyolipomas

- Cysts of the renal sinus

- Hemangioma

- Multilocular cystic nephroma

- Neuroblastoma

- Renal corticomedullary abscess

Prognosis

The prognosis in cystic renal diseases depends on extrarenal manifestations and risk for renal failure.

ADPKD will progress to renal insufficiency in patients older than 30 years and end-stage renal failure in 50% of patients. The common cause of death in ADPKD includes renal failure, hypertensive nephropathy, and subarachnoid hemorrhage.

In ARPKD, severe renal insufficiency will develop around 5 to 20 years of age. General death causes are from pulmonary disease and renal failure, usually within six weeks.

In JNPHP and MCKD, renal failure will occur within 5 to 10 years.

Acquired cystic renal disease is progressive, but regresses after transplantation.

Complications

ADPKD consists of several complications, including hypertension (most common, and develops at an earlier age), renal failure, cyst infection, severe abdominal and flank pain, and subarachnoid hemorrhage (most severe complication).

ARPKD has some complications of respiratory distress (common), portal hypertension, variceal bleeding, renal insufficiency.

JNPHP can be presented by hepatic and renal complications: Hepatic fibrosis, biliary duct enlargement, growth retardation, and renal failure.

MCKD includes hyperuricemia and gout.[8]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Genetic counseling is important for genetic cystic kidney diseases such as ADPKD and ARPKD.

Young ADPKD patients can be asymptomatic until the appearance of complications such as hypertension and renal failure. Early identification can prevent these complications by following a healthy lifestyle, such as visiting the doctor regularly, restricting salt, and exercising regularly.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) has many renal and extrarenal complications, such as hypertension, kidney failure, liver, and pancreatic cysts, and intracranial aneurysms, but has no cure yet. The complications can be treated, but renal insufficiency is progressive. Tolvaptan is a vasopressin V2 receptor (V2R) antagonist as it slows the development and growth of the cysts and thus is an effective treatment of ADPKD.[18] [Level 1]