Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Deltoid Muscle

- Article Author:

- Adel Elzanie

- Article Editor:

- Matthew Varacallo

- Updated:

- 8/22/2020 10:59:27 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Deltoid Muscle CME

- PubMed Link:

- Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Deltoid Muscle

Introduction

The deltoid muscle is a large triangular shaped muscle associated with the human shoulder girdle, explicitly located in the proximal upper extremity. The shoulder girdle is composed of the following osseous components[1][2][3]

- Proximal humerus

- Scapula

- anatomic components of the scapula also include the glenoid, acromion, coracoid process

- Clavicle

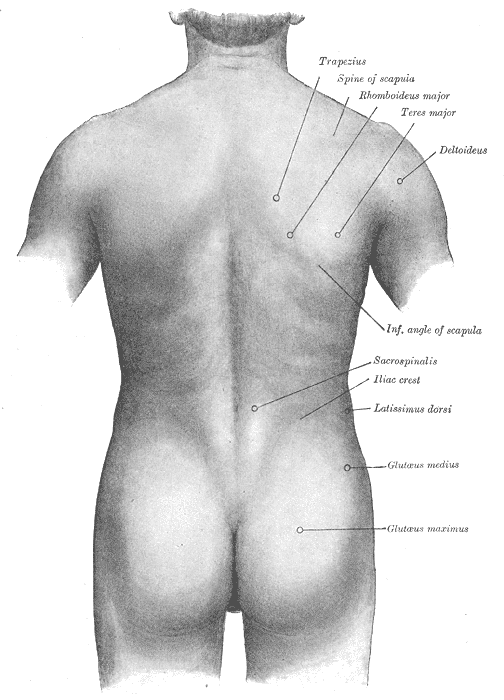

The shoulder girdle musculature, in addition to the deltoid muscle itself, includes the following[4][5][6][7][8]

- Rotator cuff (supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, subscapularis)

- Trapezius and other periscapular stabilizing muscles

- Triceps

- Latissimus dorsi

- Pectoralis major/minor

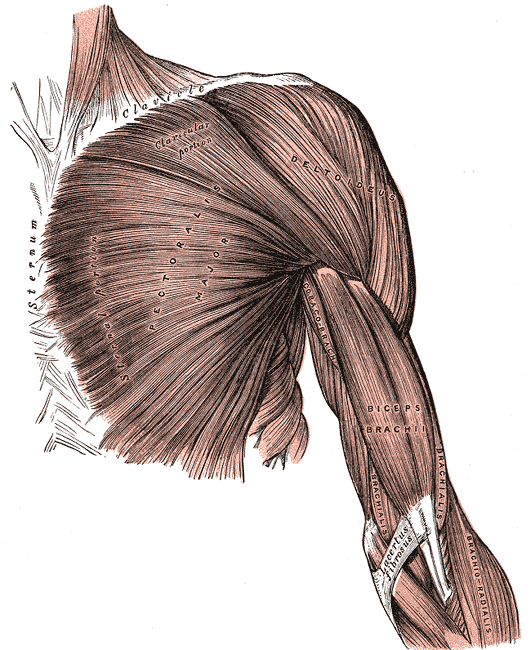

The deltoid is composed of anterior (or clavicular fibers), lateral (or acromial fibers), and posterior (or spinal fibers).[9]

Structure and Function

The deltoid is a triangular muscle. It’s base (or origin) attaches to the spine of the scapula and lateral third of the clavicle. This U-shaped origin point mirrors the insertion point for the trapezius muscle. It’s apex (or insertion) attaches to the lateral side of the body of the humerus, on a point known as the deltoid tuberosity.[9]

The deltoid divides into three distinct parts (anterior, lateral, and posterior). When all three parts contracts simultaneously, the deltoid will assist in abducting the arm past 15 degrees. It cannot initiate abduction because the direction of pull of the deltoid muscle is parallel to the axis of the humerus. Throughout abduction, the anterior and posterior parts of the deltoid play a significant role in stabilizing the arm while the lateral head assists in raising the arm from 15 to 100 degrees. Additional functions include ambulation. The anterior head of the deltoid works with pectoralis major to flex the arm when walking. This is in contrast to the posterior part of the deltoid which works with the latissimus dorsi to extend the arm during ambulation.[10]

It is also noteworthy to discuss the stabilization functions that the deltoid provides. While carrying large objects while the completely adducted (such as a dead-lift movement or carrying weights), the deltoid prevents inferior displacement of the glenohumeral joint. The deltoid also provides compensatory force during abduction of the arm. In a 2018 study, shoulders that had a rotator cuff tear required as much as 108.1% of the normal 193.8 N deltoid force to stabilize and abduct the arm 79.8 degrees.[11]

Embryology

All striated muscles of the trunk and limbs (which includes the deltoid) derive from the segmented paraxial mesoderm. The paraxial mesoderm divides into bilaterally paired blocks called somites. Myogenic precursors (myoblasts) in the somites migrate toward developing limb buds during the fifth week of development. These myoblasts condense into two major groups in the dorsal and ventral limb buds: dorsal and ventral muscle mass. The deltoid develops from the dorsal muscle mass.[12]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The deltoid receives vascular supply from the thoracoacromial branch of the axillary artery. The thoracoacromial branch originates from the second part of the axillary artery which lies posterior to the pectoralis minor. The thoracoacromial artery contributes to the deltoid branches. It travels alongside the cephalic vein in the deltopectoral groove. The deltoid muscle also receives minor contributions from the posterior circumflex artery and the deltoid branches of the profunda brachii. Although the posterior circumflex artery is not the main supply, terminal branches cross the space between the deltoid and proximal humerus, making it vulnerable to bleeding or hematoma during an anterior approach surgery to the shoulder.[13]

Lymphatic drainage of the deltoid is by the deltopectoral lymph nodes, which are located in the besides the cephalic vein within the deltopectoral groove.

Nerves

The axillary nerve innervates the deltoid. Both C5 and C6 contribute to the axillary nerve. The nerve originates from the posterior cord of the brachial plexus.[14]

Muscles

Muscles that work with the deltoid include the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor and the subscapularis. These muscles help initial abduction from 0 to 15 degrees, but also provide stabilization to the glenohumeral joint when the deltoid works to abduct past 15 degrees.

Physiologic Variants

Although rare, anatomical variants of the deltoid have been described in the literature. Several case reports have reported the posterior part of the deltoid having separate facial sheaths.[15] One case report described a complete separation of the posterior deltoid fibers with the rest of the muscle.[16] It is important to acknowledge these variants as they may generate confusion during posterior deltoid flap procedures. The surgeon may confuse this variant with the teres minor because of the location and distinct fascia.

Other noted anatomical variations include abnormal insertion into the medial epicondyle of the humerus. Here, the fibers inserted in a way that passed superficially to the brachial artery, ulnar nerve, and median nerve. Therefore, surgeons should be mindful if this variation appears and appreciate the neurovascular proximities. The literature has also reported aberrant straps of the deltoid. These straps traveled perpendicular to the posterior deltoid fibers. Surgeons should likewise know aberrant muscles as they can confuse them with other muscle fibers.

Variations of the thoracoacromial artery are also reported in the literature. As previously described, the thoracoacromial artery supplies the deltoid muscle as it runs within the deltopectoral groove with the cephalic vein. Two types of variations have been noted. In type I, it crosses the interval and tunnels into the deltoid muscle. In type II, it crosses the interval and runs with the cephalic vein. However, it will then cross back and toward the pectoralis major.[17]

Surgical Considerations

The deltoid is a significant factor when considering the anterior surgical approach to gain access to the shoulder joint. Some of these technical procedures include, but are not limited to the following:

- Open Bankart repair/capsular reconstructions

- indicated in the setting of recurrent anterior (or other directional) instability of the shoulder

- Shoulder arthroplasty

- indicated for cases of post-traumatic deformity, advanced degenerative arthritis, and/or avascular necrosis

- includes hemiarthroplasty, total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA), reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (rTSA)

- Long head of the biceps tendon (LHBT) repair versus tenotomy versus tenodesis procedures

- Rotator cuff repair

- contemporary indications remain somewhat controversial although most of these procedures are now being performed arthroscopically

- popular approaches (as opposed to the deltopectoral approach) include the mini-open approach (lateral deltoid-splitting approach)

Deltopectoral (DP) approach

When marking out the anatomic landmarks for the DP approach, the coracoid process is marked on the skin to plan out the trajectory for the surgical incision. From there, an incision is made which follows over the deltopectoral groove. The deltoid and pectoralis major muscle fibers are appreciated, and this most often includes direct visualization of a "fat stripe" which includes the cephalic vein in the center of the incision/approach.

The deltoid is retracted laterally while the pectoralis major muscle is retracted medially. The cephalic vein is retracted either laterally or medially (depending on surgeon preference).[20]

Other approaches

Other surgical approaches that involve the deltoid are the anterolateral and direct lateral approach to the shoulder. A modified anterolateral approach can be preferred over the more anterior approach for humeral fractures because this may facilitate access to the specific fracture fragments.[21]

The anterolateral approach to the acromioclavicular joint and subacromial space is used primarily for repair of the rotator cuff and anterior decompression of the shoulder joint. This incision uses the coracoid process and the acromion as landmarks. After the acromioclavicular joint is exposed, retraction of the deltoid is required. If the surgery requires repairs of the rotator cuff, splitting of the deltoid muscle is required. According to a 2018 study, the anterolateral surgical is especially useful when exposing the posterior aspect of the shoulder.[22]

The lateral approach also requires the splitting of the deltoid. It involves a 5 cm longitudinal incision from the acromion to the lateral aspect of the arm. Division of the deltoid is necessary, which includes splitting it downwards for 5 cm. Like the anterolateral approach, it requires a suture at the apex of the incision for inadvertent splitting and axillary nerve damage. Minimally invasive approaches to the shoulder also involve splitting of the deltoid. The lateral minimally invasive technique requires making two incisions of the deltoid. One will be proximal, and one will be distal with the axillary nerve running in between the two incisions. The minimally invasive anterolateral part involves pressing a guide wire through the substance of the deltoid. Radiographic imaging will confirm the placement, which subsequently leads to splitting of the deltoid.

Complications

Complications relating to these surgical approaches include deltoid injuries. One of these complications involves detachment of the deltoid from the clavicle. Reattachment of the deltoid would require full thickness sutures and transosseous sutures along with 4-6 weeks of complete healing. The deltoid is also at risk for being denervated. The axillary nerve runs under the deltoid muscle and travels posterior to anterior. It is at risk if the anterior deltoid is vigorously retracted laterally or if retractor placement is under the deltoid. Denervation can cause loss of arm abduction past 15 degrees and loss of sensory over the deltoid. Incorrect retraction of the deltoid also might also lead cephalic vein rupture which will lead to upper limb edema.

Clinical Significance

The deltoid's function is testable in the clinical setting. It is done by manually raising the patient’s arm 15 degrees. After this, ask the patient to abduct the arm against resistance. In patients who have normal deltoid function, the arm will contract, and the lateral deltoid contraction will be appreciated via palpation. In patients who have a dysfunctional deltoid, these clinical findings will not be present. A deltoid dysfunctional problem commonly arises due to axillary nerve palsy. Common etiologies of this condition include overuse of a crutch, surgery, or posterior shoulder dislocation from severe trauma.

Other Issues

The inability to abduct the arm does not specifically indicate that there is a dysfunction with the deltoid. The inability to abduct the arm presents during proximal neuromuscular disorders. Neurological problems include Lambert Eaton disease.[23] Muscular inflammatory processes polymyositis/dermatomyositis,[24] polymyalgia rheumatica (stiffness rather than weakness), and as a side effect of aluminum hydroxide containing vaccines.[25] These conditions could all present with proximal muscle weakness or with the inability to abduct the arm. Other differential diagnoses for patients with deltoid weakness include cachexia from chronic disease or malnourishment. All clinicians keep these differentials in mind upon finding the patient's inability to abduct the upper limb.

(Click Image to Enlarge)