Anatomy, Head and Neck, Digastric Muscle

- Article Author:

- Eve Tranchito

- Article Editor:

- Bruno Bordoni

- Updated:

- 8/15/2020 11:34:46 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Anatomy, Head and Neck, Digastric Muscle CME

- PubMed Link:

- Anatomy, Head and Neck, Digastric Muscle

Introduction

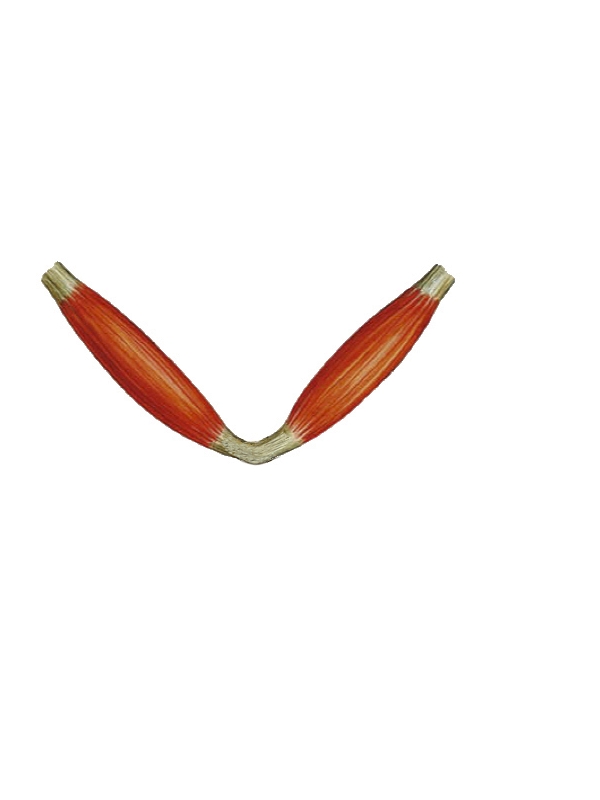

The digastrics are a pair of muscles individually made up of two distinct muscle bellies: the anterior and posterior digastrics. They derive embryonically from the first and second pharyngeal arches. Together, they function in swallowing, chewing, and speech, and serve as important surgical landmarks in neck dissections and are used routinely for reconstruction. Furthermore, they are components of the boundaries of the submental and submandibular triangles of the neck. There are numerous anatomical variants of the digastrics which can be misleading on MRI or CT. Careful consideration of these variations is critical in clinical assessment and surgical planning.

Structure and Function

The neck contains a pair of digastric muscles, each of which subdivides into an anterior and posterior belly. The two bellies connect by an intermediate tendon. The anterior belly of the digastric attaches near the midline of the base of the mandible on the digastric fossa and runs toward the hyoid. The posterior belly attaches to the temporal bone at the mastoid process and slopes to meet the intermediate tendon. The intermediate tendon typically courses through the stylohyoid muscle, but variations are found lying medial or lateral to it. The tendon runs through a fibrous loop attached to the hyoid bone at the body and greater cornu.[1] The anterior belly of the digastric divides the submental and submandibular triangles of the neck. The submandibular triangle, bordered by the anterior and posterior bellies of the digastric and the inferior border of the mandible, houses the submandibular gland, anterior facial vein, submental artery, mylohyoid nerve and vessels, and the external carotid. The submental triangle is bordered laterally by the anterior belly and houses lymph nodes that drain the floor of the mouth and part of the tongue.[2] The posterior belly of the digastric also serves as a boundary for the carotid triangle, which is where the facial artery branches from the external carotid.[3]

The digastric muscle functions during swallowing, chewing, and speech. The anterior belly of the digastric is one of the three suprahyoid muscles which stabilizes the hyoid during swallowing, an action critical in protecting the airway while eating. Furthermore, the digastrics work to depress the mandible for jaw opening, chewing, and speech.[4] The contraction of the posterior digastric muscle participates in the extension of the head.

The infrahyoid muscles are the antagonistic muscles to the digastric.

Embryology

The embryologic period occurs during the first eight weeks following fertilization. During this time, neural crest cells migrate caudally to form the five pharyngeal arches. The first and second pharyngeal arches give rise to the anterior and posterior bellies of the digastrics as well as their respective nerve supplies. The anterior belly of the digastric and the mylohyoid nerve form from the first pharyngeal arch, also known as the mandibular arch. The posterior belly of the digastric and the facial nerve derive from the second pharyngeal arch or the hyoid arch. Other muscular structures derived from the first pharyngeal arch include the mylohyoid, tensor veli palatini, tensor tympani, and the muscles of mastication including the temporalis, masseter, and medial and lateral pterygoids. In addition to the posterior belly of the digastric, the second pharyngeal arch gives rise to the stapedius, buccinator, auricular, occipitofrontalis, facial muscles, platysma, and stylohyoid muscles.[5] Researchers postulate that the wide array of anatomical variants of the anterior belly of the digastric is mostly a result of complex morphogenesis of the first pharyngeal arch.[1]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The submental artery, a branch of the facial artery, supplies blood to the anterior belly of the digastric. It runs between the submandibular gland and mylohyoid muscle. The posterior auricular artery and occipital artery, branches of the external carotid artery, supply blood to the posterior belly of the digastric.[5]

Nerves

The anterior belly of the digastric receives innervation from the mylohyoid nerve. The mylohyoid nerve is a branch of the inferior alveolar nerve, which arises from the mandibular branch of the trigeminal nerve.[5] It branches off before the inferior alveolar nerve penetrates the mandibular foramen and courses through the mylohyoid canal before giving off motor branches to both the mylohyoid muscle and anterior belly of the digastric muscle.[6] The facial nerve provides nerve supply to the posterior belly of the digastric.

Muscles

The lateral face of the posterior belly is in relationship with the sternocleidomastoid muscles, very long neck muscle and splenius capitis; the medial face is related to the lateral rectus muscle of the head.

The anterior belly is laterally covered by the skin planes and the platysma muscle while, medially, it rests on the mylohyoid muscle.

Physiologic Variants

The anterior belly of the digastric is more likely to have anatomical variations than the posterior belly; variations of the anterior belly of the digastric occur in up to 65.8% of the population. Of those reported, it is far more likely to have unilateral than bilateral variants. Many of these variants are accessory muscle bellies with varying origins and insertions. Reports also exist of variations of the nerve supply in which the anterior belly receives innervation from both the facial nerve and mylohyoid nerve.[7] There are no confirmed clinical consequences of these variants.[5] The intermediate tendon may not pierce the stylohyoid muscle but may lean over or laterally.

Surgical Considerations

The digastrics serve as a significant surgical landmark in neck dissections; the posterior belly is used to help identify the course of the spinal accessory nerve, internal jugular vein, carotid arteries, and hypoglossal nerve. It can also help identify ansa cervicalis in reconstruction cases. The anterior belly of the digastric is often included in submental flaps during facial reconstruction, as the submental vessels frequently course deep to the muscle. The intermediate tendon of the digastric can be attached to the tongue to help avoid stridor and subsequent need for tracheostomy in patients who undergo resection of the anterior mandibular arch. The digastrics may be used as a flap to restore a symmetrical smile to those with injury to the marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve.[5] The digastric can be sutured to the mandible in neck dissections for primary tongue cancer resection to accomplish laryngeal suspension.[8]

Clinical Significance

Careful consideration of anatomical variations should be taken during clinical evaluation and surgical planning so as not to be mistaken for a neck mass. Knowledge of this possible occurrence is important for both the surgeon and the radiologist. The digastric muscles may be implicated in post-radiation dysphagia, or swallowing dysfunction.[9] Post-radiation changes leading to atrophy or fibrosis of the digastric is a possible sequela in patients who have undergone post-operative radiotherapy for oral cancer.[10]

Exercises targeting the suprahyoid muscles, including the anterior belly of the digastric, are thought to help patients with dysphagia.[11][12]

Calcification of the digastric muscle may be the cause (together with an alteration of the styloid ligament, such as length or calcification) of styloid process neuralgia; the latter also has the names long styloid process syndrome or Eagle syndrome. Muscle calcification could cause various symptoms, such as throat disorders, ear pain, and pharyngeal pain. The patient may have pain during tongue movement or head movements. In most clinical cases, surgery is necessary.

The digastric muscle is involved in the causes of pain relative to bruxism or the habit of clenching teeth. A myofunctional physiotherapy or speech therapy can reduce the electrical activity of the muscle during the movement of the jaw and reduce pain.

The digastric muscle in its posterior portion could be the site of a rare complication of otitis media: a Citelli abscess. The resolution is surgical.

The presence of trigger points in the digastric muscle can cause referred pain to the teeth. The therapy is of myofunctional type.

Other Issues

There are few reports of intramuscular hemangiomas of the digastric muscles.[13]

In a very small percentage of people, agenesis of the anterior belly is an anomaly.