Diphyllobothrium Latum

- Article Author:

- Muhammad Durrani

- Article Author:

- Hajira Basit

- Article Editor:

- Eric Blazar

- Updated:

- 6/30/2020 2:37:29 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Diphyllobothrium Latum CME

- PubMed Link:

- Diphyllobothrium Latum

Introduction

Diphyllobothriasis represents an intestinal parasitic zoonotic infection caused by the cestode Diphyllobothrium. Diphyllobothrium latum (D. latum), which is the most common cause of diphyllobothriasis, also called the “fish tapeworm” or the “broad tapeworm,” is transmitted to humans by the ingestion of fish which harbor infectious larvae of the genus Diphyllobothrium causing a wide-ranging spectrum of disease and severity.[1] This infection has started to garner more attention secondary to a recent surge in human cases, but reports of diphyllobothriasis date as far back as the prehistoric period and Diphyllobothrium eggs have been identified as far back as 3917 B.C. in Germany.[2] Freshwater fish serve as the primary epidemiological reservoir for D. latum, while other Diphyllobothrium species originate from marine fishes.[1][3] Thus, the fundamental risk factor is the consumption of raw freshwater or marine fish with human disease occurring after maturation of larval stages of the tapeworm in the hosts’ intestine.

Etiology

Diphyllobothriasis occurs from the ingestion of larval forms of the fish tapeworm, with the most common species being D. latum. Molecular identification analyses have revealed numerous genus and species with potential for human infectivity. Each species is associated with specific hosts and has the potential to cause infectivity of varying degrees in their host. Thus far, researchers have identified a total of 14 described species of genus Diphyllobothrium.[1]

Epidemiology

Diphyllobothriasis can affect any age group and gender, but the majority of identified cases were middle-aged men. This parasitic infection can be a public-health issue for residents and travelers in endemic as well as non-endemic regions. The fish tapeworm, D. latum, has historically been implicated in human illness for thousands of years. The current state of knowledge regarding these parasites points to cohabitation with humans since the early Neolithic period.[2] Epidemiologic studies have concluded that in the 1970s, this infection was estimated to have affected 9 million individuals globally with newer data estimating 20 million people currently infected worldwide.[4][5] Additionally, in recent years, certain areas of the world have seen a re-emergence of diphyllobothriasis thought to be secondary to changes in eating habits as well as globalization.

Furthermore, it is postulated that with changes in eating habits, combined with rapid freezing techniques, there will be an increased speed at which potential fish-borne tapeworm infections will start to arise.[1] Despite this, diphyllobothriasis has suffered from decreased awareness among the public sector and medical professionals. When paired with the need for specialized diagnostic testing, underdiagnosis of diphyllobothriasis is likely when accounting for the true prevalence and incidence. Since diphyllobothriasis is mostly a function of consumption and contact with fish, specific individuals are at higher risk of disease transmission; this includes fisherman, who consume their fresh catches and individuals who consume uncooked fish regularly.[4]

Pathophysiology

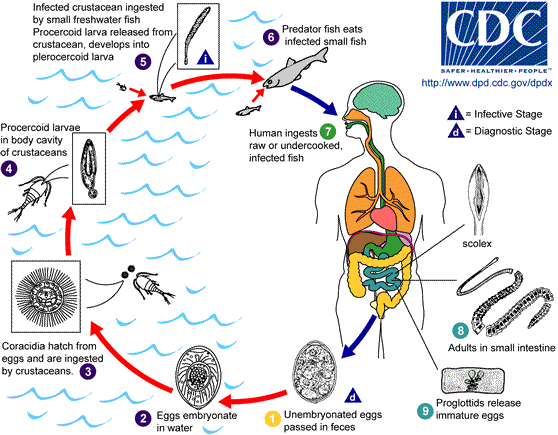

The life cycle of D. latum, as it relates to humans, begins when un-embryonated eggs are released into the feces of humans that were infected with the intestinal parasite. These eggs will become embryonated in water under appropriate conditions, with the process usually lasting 18 to 20 days. During this maturation process, oncospheres, which are the first larval forms of the tapeworm, materialize within the egg. The oncosphere is then covered by an outer envelope that contains cilia and is called a coracidium. This coracidium hatches from the egg in the surrounding water and becomes a free-swimming larval stage that subsequently goes on to attract the first intermediate host. The free-swimming coracidium is consumed by the first intermediate host. This is usually an aquatic arthropod, such as crustaceans from the subclass Copepoda.

Next, within these copepods, the second larval stage of D. latum develops, called the procercoid. This occurs through a complex host of interactions where the coracidium penetrates the intestinal wall of the first intermediate host. This procercoid stage contains six embryonic hooks on its posterior appendage, which helps to anchor it. When the infected crustacean is ingested, usually by freshwater or marine fish, this second intermediate host now takes over as the site of further larval maturation. The ingestion of the copepod allows the procercoid larvae to be released, and they migrate to enter the tissues of the second intermediate host in order to develop into the third larval stage called the plerocercoid. This is the infective stage of the larvae, and when these smaller second intermediate hosts are consumed by larger fish, the plerocercoid will migrate to the musculature of these larger fishes. Human transmission occurs when humans consume these raw or undercooked fish that are infected with D. latum.[4]

In humans, the plerocercoid develops into mature tapeworms, which attach and reside in the intestine. The fecundity, which is the reproductive potential of these tapeworms, is extremely high, and one tapeworm is estimated to produce up to 1 million eggs per day.[6] Once established, the tapeworm infection is postulated to induce changes in the concentration of several neuromodulators in the host tissue and serum.[7] Additionally, D. latum infection has been shown to cause structural changes locally, leading to altered gastrointestinal tract functioning by modulating the neuroendocrine response and causing enhanced secretion as well as changing gut motility.[7] Additionally, studies have shown that damage caused by these infections are also mediated through induction of mast cell and eosinophilic granule cell degranulation, leading to the release of inflammatory cytokines.[7] Infection with D. latum has also been shown to lead to anemia secondary to dissociation of vitamin B12 from its intrinsic factor complex in the gut, which is due to the faster absorption rate of vitamin B12 by the tapeworm relative to the human gut.[4]

Histopathology

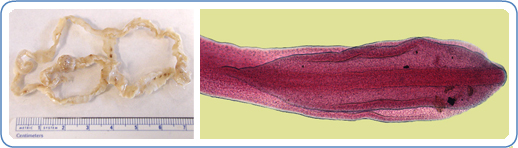

D. latum is the longest human tapeworm and is typically 4 to 15 meters in length but can grow up to 25 meters within the human intestine. The rate of growth may exceed 22 cm/day, and they may remain active in the gut for over 20 years.[4] D. latum is characterized by an anterior end called a scolex with attachment grooves on its dorsal and ventral surfaces.[4][8] The body of the tapeworm is composed of many segments, each containing sets of male and female reproductive organs, allowing for its high fecundity.[4]

History and Physical

Diagnosis of the fish tapeworm requires a thorough history with particular attention to the patient’s occupation, hobbies, eating habits, and travel history. Diphyllobothriasis is known to occur in both endemic and non-endemic areas as a result of globalization. As mentioned previously, it is associated with the consumption of raw or poorly cooked fish. Additionally, due to its extremely high fecundity, it is easily spread in regions with poor hygiene and sanitary practices. Human infection with D. latum can range from an asymptomatic state to mild gastrointestinal symptoms to severe cases of anemia as well as luminal obstruction. Studies have shown that in patients infected with D. latum, twenty-five percent will manifest symptoms of abdominal pain, diarrhea, fatigue, headaches, or pernicious anemia.[9]

A Korean study looking at D. latum infections identified a total of 49 cases between 1971 and 2012. When looking at the composite data in these cases, the patients were most commonly men between the ages of 30 and 49.[10] The significant signs and symptoms encountered were abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, in addition to dizziness, myalgia, anemia, fatigue, and dyspepsia.[9] In another Korean study looking at D. latum infections, all identified patients were males between the ages of 17 and 35 with primarily abdominal pain and distension as presenting complaints.[11] A case series in 2012 looked at 20 cases of confirmed diphyllobothriasis and found that the most frequently reported symptoms were fatigue and mild abdominal discomfort, identified in 66.6% of patients.[12] A larger Japanese study from 2012 to 2015 with 139 patients with confirmed D. latum infection revealed mild diarrhea as the most common symptom following by abdominal pain.[13]

Diphyllobothriasis can affect different organ systems with varied manifestations and are listed below based on published case reports and series:

- Central nervous system manifestations include paresthesia, demyelinating symptoms secondary to prolonged anemia and vitamin B12 deficiency, headaches, and encephalopathy.[4]

- Ocular manifestations include optic neuritis secondary to long-standing vitamin B12 deficiency.[4][14]

- Gastrointestinal manifestations include acute abdominal pain, diarrhea, constipation, intestinal obstruction, subacute appendicitis, cholecystitis, as well as cholangitis.[4][9]

- Hematological manifestations include megaloblastic anemia, vitamin B12 deficiency, pancytopenia, eosinophilia, and pernicious anemia.[4][12]

- Respiratory manifestations include dyspnea in the setting of severe vitamin B12 deficiency.[4]

- Dermatological manifestations include glossitis and allergic symptoms, as well as pallor.[4]

Evaluation

In the appropriate clinical picture with signs and symptoms consistent with diphyllobothriasis, the clinician should consider initial laboratory workup. Laboratory workup may reveal peripheral eosinophilia and megaloblastic anemia along with vitamin B12 deficiency.[4] In general, the diagnosis of D. latum is from the presence of eggs or proglottids of the representative shape and structural characteristics in the patient’s stool sample.[4] This allows for the diagnosis at the genus level. Molecular methods to identify D. latum are also available and allow for a more reliable tool to identify the infection down to the species level, which is clinically more relevant for epidemiological studies and includes the use of PCR and restriction fragment length polymorphisms. Additional tests found in the literature include endoscopy, abdominal magnetic resonance imaging, and colonoscopy, but these are both costly and invasive.[15] Humans infected with D. latum will begin to pass eggs in their stools on average 15 to 45 days after the ingestion of the plerocercoid stage of larvae.[4]

Treatment / Management

Treatment for this parasitic infection, as well as most tapeworm infections, is praziquantel in those without contraindications. A 25 mg/kg dose is noted to be highly effective against D. latum infections.[4][16][17] Lower doses at 10 mg/kg have been noted to be effective against other species of Diphyllobothrium but have shown poor efficacy against D. latum in experimental animal models.[4] A single dose was found to have high cure rates. Side effects of praziquantel include weakness, headache, dizziness, abdominal pain, fever, and possibly urticaria.[4][17]

An alternative anthelminthic drug used for D. latum infections is a single dose of niclosamide, which is given either in a single 2-gram dose for adults or a 1-gram dose for children older than six years of age.

Praziquantel can be given in pregnancy.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes influenza, as well as other helminthic diseases, and can be very broad due to the non-specific symptoms encountered, especially if the clinician neglects to obtain information regarding the consumption of raw or undercooked fish in the initial history.

Prognosis

The prognosis of D. latum infections will depend on the patient’s disease severity, comorbid conditions, as well as worm burden within the intestinal tract. Despite this, the prognosis is excellent, and treatment of this condition is effective.

Complications

Patients infected with D. latum are usually asymptomatic or present with a mild disease but may have complications if the worm burden is high this usually manifests secondary to severe vitamin B12 deficiency and its complications, including megaloblastic anemia and development of subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord as well as cognitive decline.[18]

Deterrence and Patient Education

The best way to prevent infection with D. latum is to avoid the consumption of raw fish. Food safety practices include cooking the fish well or freezing fish at -18 degrees Celsius for 24 to 48 hours to prevent infection.[4]

Pearls and Other Issues

- Diphyllobothriasis is caused by the fish tapeworm D. latum and is a zoonotic infection mostly attributed to the consumption of raw or undercooked fish.

- Diagnosis relies on thorough patient history, asking about occupational history, hobbies, travel history, eating habits, as well as maintaining a high index of suspicion.

- Most infected individuals present with a mild illness characterized by abdominal pain or discomfort, diarrhea, and malaise.

- Laboratory testing is largely non-specific but may reveal eosinophilia as well as vitamin B12 deficiency, megaloblastic anemia, and/or pernicious anemia.

- Diagnosis is clinical, but confirmation via stool testing is an option.

- Treatment is with a single dose of praziquantel, which is safe in pregnancy.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Given the effect of globalization and the prevalent habit of consuming raw or undercooked fish, clinicians, nurse practitioners, nurses with specialty training in infectious diseases, pharmacists, and public health officials should be aware of the reemergence of diphyllobothriasis, as part of an interprofessional healthcare team approach. The pharmacist should educate the patient on the importance of medication compliance.

Efforts to prevent the spread and acquisition of this disease will rely on a team-based approach to addressing water contamination around the world, anticipating the effect of climate change on parasites, and raising awareness for travelers and locals in endemic areas. [Level 5]

(Click Image to Enlarge)