Esophageal Varices

- Article Author:

- Marcelle Meseeha

- Article Editor:

- Maximos Attia

- Updated:

- 8/10/2020 5:22:38 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Esophageal Varices CME

- PubMed Link:

- Esophageal Varices

Introduction

Esophageal varices are dilated submucosal distal esophageal veins connecting the portal and systemic circulations. This happens due to portal hypertension (most commonly a result of cirrhosis), resistance to portal blood flow, and increased portal venous blood inflow. The most common fatal complication of cirrhosis is variceal rupture; the severity of liver disease correlates with the presence of varices and risk of bleeding.[1][2][3][4]

The portal vein has a circulation of over 1500 ml/min of blood and if there is an obstruction, this results in elevated portal venous pressure. The response of the body to the increased venous pressure is the development of collaterals. these portosystemic collaterals divert blood from the portal venous system to the inferior and superior vena cava. At the same time, one important system is the gastroesophageal collaterals that drain into the azygos vein and lead to the development of esophageal varices. When these varices get enlarged, they rupture producing severe hemorrhage. Bleeding from esophageal varices is the third most common cause of upper GI bleeding, after duodenal and gastric ulcers.

Etiology

Causes of portal hypertension:

- Prehepatic: Portal vein obstruction (EHPVO) or massive splenomegaly with increased splenic vein blood flow

- Posthepatic: Severe right-sided heart failure, constrictive pericarditis, and hepatic vein obstruction (Budd-Chiari syndrome)

- Intrahepatic: Cirrhosis accounts for most cases of portal hypertension.

Less frequent causes are schistosomiasis, massive fatty change, diseases affecting portal microcirculation as nodular regenerative hyperplasia and diffuse fibrosing granulomatous disease as sarcoidosis.[5]

Other rare causes of portal hypertension include:

- Wilson disease

- Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency

- Primary biliary cirrhosis

- Tuberculosis

- Constrictive pericarditis

Epidemiology

Incidence

- At diagnosis, 30% of cirrhotic patients have varices which increase to 90% in 10 years.

- The 1-year rate of first variceal bleeding is 5% for small varices, 15% for large varices.

Portal hypertension is common in chronic liver disease (CLD) in children.

Prevalence

- It is more common in males than in females. Fifty percent of patients with esophageal varices will experience bleeding at some point.

- Variceal bleeding has a 10% to 20% mortality rate in the 6 weeks following the episode.

In the West, the two common causes of portal hypertension are alcohol and viral hepatitis. In Asia and Africa, the most common causes of portal hypertension include schistosomiasis and hepatitis B/C.

Pathophysiology

Portal hypertension causes portocaval anastomosis to develop to decompress portal circulation. Normal portal pressure is between 5-10 mmHg but in the presence of portal obstruction, the pressure may be as high as 15-20 mmHg. Since the portal venous system has no valves, resistance at any level between the splanchnic vessels and right side of the heart results in retrograde flow and elevated pressure. The collaterals slowly enlarge and connect the systemic circulation to the portal venous system. Over time, this leads to a congested submucosal venous plexus with tortuous dilated veins in the distal esophagus. Variceal rupture results in hemorrhage.

Pathophysiology of portal hypertension:

- Increased resistance to portal flow at the level of hepatic sinusoids is caused by:

- Intrahepatic vasoconstriction due to decreased nitric oxide production, and increased release of endothelin-1 (ET-1), angiotensinogen, and eicosanoids

- Sinusoidal remodeling disrupting blood flow.

- Increased portal flow is caused by hyperdynamic circulation due to splanchnic arterial vasodilation through mediators such as nitric oxide, prostacyclin, and TNF.

Risk factors for variceal bleeding:

- Size of the varices; the larger the varix, the greater the potential for rupture

- Advanced Child classification also increases the risk of hemorrhage

- Presence of red color markings on the varices during endoscopy is also associated with a potential for rupture

- Active alcohol consumption

History and Physical

The first indication of varices is often the presence of a gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding episode: hematemesis, hematochezia, and/or melena. Occult bleeding (anemia) is uncommon.

History

- Variceal bleed can be the initial presentation of previously undiagnosed cirrhosis

- Alcoholism, exposure to blood-borne viruses

- Hematemesis, melena, or hematochezia

- Rapid upper GI bleed can present as rectal bleeding.

- Weight loss in patients with chronic liver disease

- Anorexia

- Abdominal discomfort

- Jaundice

- Pruritus

- Encephalopathic symptoms- altered mental status

- Muscle cramps

Physical Exam

- Assess hemodynamic stability: hypotension, tachycardia (active bleeding)

- Abdominal exam: liver palpation/percussion (often small and firm with cirrhosis)

- Splenomegaly, ascites (shifting dullness; puddle splash)

- Visible abdominal periumbilical collateral circulation (caput-medusae)

- Peripheral stigmata of alcohol abuse: spider angiomata on chest/back, palmar erythema, testicular atrophy, gynecomastia, palmar erythema

- Testicular atrophy

- Venous hums

- Anal varices or blood on rectal exam

- Hepatic encephalopathy; asterixis.

Evaluation

Initial Tests (lab, imaging)

- Anemia: Hemoglobin may be normal in active bleeding and may take six to 24 hours to equilibrate. Other causes of anemia are common in cirrhotics

- Thrombocytopenia is the most sensitive and specific lab parameter that correlates with portal hypertension and large esophageal varices

- Elevated aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase, bilirubin; prolonged PT, low albumin suggest cirrhosis

- BUN is often elevated in GI bleed

- Sodium level may drop in patients treated with terlipressin

- coagulation profile

- Renal function

- Arterial blood gas

- Hepatitis serology

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy

- Can identify actively bleeding varices as well as large varices and stigmata of recent bleeding

- Can be used to treat bleeding with esophageal band ligation (preferred to sclerotherapy); prevent rebleeding; detect gastric varices, portal hypertensive gastropathy; diagnose alternative bleeding sites

- Can identify and treat nonbleeding varices (protruding submucosal veins in the distal third of the esophagus)

Diagnostic Procedures/Other

- Transient elastography (TE) for identifying CLD patients at risk of developing clinically significant portal hypertension (CSPH)

- Hepatic vein pressure gradient (HVPG) greater than 10 mmHg is the gold standard to diagnose CSPH (normal: 1 mmHg to 5 mmHg)

- HVPG response of equal or greater than 10% or to less than or equal to 12 mmHg to intravenous propranolol may identify responders to nonselective beta-blocker (NSBB) and is linked to a significant decrease in risk of variceal bleeding

- Video capsule endoscopy screening may be an alternative to traditional endoscopy

- Doppler sonography (second line): demonstrates patency, diameter, and flow in the portal and splenic veins, and collaterals; sensitive for gastric varices; documents patency after ligation or transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS)

- CT or MRI-angiography (second-line, not routine): demonstrates large vascular channels in abdomen, mediastinum; demonstrates patency of intrahepatic portal and splenic vein

- Venous-phase celiac arteriography: demonstrates portal vein and collaterals; diagnosed hepatic vein occlusion

- Portal pressure measurement using a retrograde catheter in the hepatic vein.

- Ultrasound of the abdomen may reveal biliary obstruction (eg cancer)

Treatment / Management

Treat underlying cirrhotic comorbidities.[6][7][8][9]

Hepatic encephalopathy and infection often complicate variceal bleeding.

Active bleeding:

- Intravenous (IV) access, hemodynamic resuscitation

- Overtransfusion increases portal pressure and increases rebleeding risk

- Treat coagulopathy as necessary. Fresh frozen plasma may increase blood volume and increase rebleeding risk

- Monitor mental status. Avoid sedation, nephrotoxic drugs, and beta-blockers acutely.

- IV octreotide to lower portal venous pressure as adjuvant to endoscopic management. IV bolus of 50 micrograms followed by a drip of 50 micrograms/hr.

- Terlipressin (alternative): 2 mg q4h IV for 24 to 48 hours, then 1 mg q4h

- Erythromycin 250 mg IV 30 to 120 minutes before endoscopy

- Urgent upper GI endoscopy for diagnosis and treatment

- If no contraindication, start beta-blocker (nitrates are an alternative)

Variceal band ligation is preferred to sclerotherapy for bleeding varices and for nonbleeding medium-to-large varices to decrease bleeding risk. Ligation has lower rates of rebleeding, fewer complications, more rapid cessation of bleeding and a higher rate of variceal eradication.

Repeat ligation/sclerosant for rebleeding.

If endoscopic treatment fails, consider self-expanding esophageal metal stents or peroral placement of Sengstaken-Blakemore-type tube up to 24 hours to stabilize the patient for TIPS.

As many as two-thirds of patients with variceal bleeding develop an infection, most commonly spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, UTI, or pneumonia. Antibiotic prophylaxis with oral norfloxacin 400 mg or IV ceftriaxone, 1 g q24h for up to a week, is indicated.

With active bleeding, avoid beta-blockers, which decrease blood pressure and blunt the physiologic increase in heart rate during acute hemorrhage.[10][11][12]

Prevent recurrence of acute bleeding:

- Vasoconstrictors: terlipressin, octreotide (reduce portal pressure)

- Endoscopic band ligation (EBL): if bleeding recurs/portal pressure measurement shows portal pressure remains greater than 12 mmHg

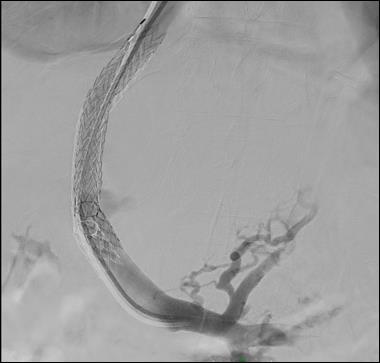

- TIPS: Second-line therapy if the above methods fail; TIPS decreases portal pressure by creating communication between hepatic vein and an intrahepatic portal vein branch.

Medications

First-Line

- NSBB reduce portal pressure and decrease the risk of the first bleed from 25% to 15% in primary prophylaxis

- Carvedilol: 6.25 mg daily is more effective than NSBB (Propranolol and Nadolol) in dropping HVPG

- Chronic prevention of rebleeding (secondary prevention): NSBBs and EBL reduce the rate of rebleeding to a similar extent, but beta-blockers reduce mortality, whereas ligation does not.

Second-Line

- Obliterate varices with esophageal banding for patients not tolerant of medication prophylaxis.

- During ligation, proton pump inhibitors are used, such as lansoprazole 30 mg/day, until varices are obliterated.

- Management of Budd-Chiari syndrome: anticoagulation, angioplasty/thrombolysis, TIPS, and orthotopic liver transplantation

- Management of extrahepatic portal vein obstruction: anticoagulation; mesenteric-left portal vein bypass (Meso-Rex procedure).

Refer for endoscopy, liver transplant, and interventional radiology for TIPS.

Pneumococcal and hepatitis A/B (HAV/HBV) vaccine need to be considered.

Surgery/Other Procedure

- Esophageal transection: in rare cases of uncontrollable, exsanguinating bleeding

- Liver transplantation

- Portosystemic shunt

- Inpatient admission to the intensive care unit to stabilize acute bleeding and hemodynamic status, therapeutic endoscopy.

- Discharge criteria: bleeding cessation; hemodynamic stability and appropriate plan for treating comorbidities.

Radiology

Percutaneous transhepatic embolization has been used to stop variceal bleeding. However, its effectiveness remains questionable. It is generally reserved for patients who are not candidates for surgery.

TIPS is a salvage procedure to stop acute variceal bleeding. However, the procedure is also associated with serious complications including encephalopathy and occlusion of the shunt within 12 months. TIPS may be a bridge to a liver transplant.

Differential Diagnosis

- Acute gastric erosions

- Duodenal ulcers

- Gastric ulcers

- Gastric cancer

- Mallory- Weiss tear

- Nasogastric tube trauma

- Portal hypertensive gastropathy

Prognosis

Once a patient has a single episode of variceal bleeding, there is a 70% chance of a rebleed. At least 30% of rebleeding episodes are fatal. Most deaths occur within the first few days after the bleed. Mortality rates are highest in the presence of surgical intervention and for acute variceal bleeding.

Complications

- Aspiration

- Multiorgan failure

- Encephalopathy

- Perforation of the esophagus

- Death

Pearls and Other Issues

Endoscopic variceal ligation should be repeated every 1 to 4 weeks until varices are eradicated. If TIPS is done, repeat endoscopy to assess rebleeding. Endoscopic screening should be done in patients with known cirrhosis every two to three years and yearly in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. Patients with liver stiffness less than 20 kPa and with platelets greater than 150,000 can avoid endoscopic screening and may follow up by annual TE and platelet count.

Prognosis

- In cirrhosis, one-year survival is 50% for those surviving two weeks following a variceal bleed.

- In-hospital mortality remains high related to the severity of underlying cirrhosis, ranging from 0% in Child A to 32% in Child C disease.

- Prognosis in noncirrhotic portal fibrosis is better than for cirrhotics.

Complications

- Formation of gastric varices after eradication of esophageal varices

- Esophageal varices can recur.

- Hepatic encephalopathy, renal dysfunction, hepatorenal syndrome

- Infections after banding/ligation of varices

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The management of esophageal varices is with an interprofessional team that consists of a gastroenterologist, internist, surgeon, invasive radiologist, and an intensivist. The treatment selected depends on the severity of the disease and patient status.this is a serious life-threatening disorder and all patients should be in a monitored setting. The role of the nurse in monitoring is crucial. Vitals and oxygenation should be continuously monitored. Blood work should be followed to ensure that the patient is not anemic and developing renal or liver dysfunction. The pharmacist should have the key medications to stop the variceal hemorrhage. In addition, all drugs that are liver toxic should be discontinued. Because patients tend to have other comorbidities, nurses should ensure that the patient has DVT and pressure ulcer prophylaxis. Several treatments to stop variceal bleeding have the potential to cause complications including perforation of the esophagus. Thus, close monitoring of the patient is critical; nurses should regularly check for emphysema. Close communication between the team is vital if outcomes are to be improved.

Unless the primary cause of portal hypertension is controlled, recurrence is common with all treatments. The prognosis for patients with esophageal varices is guarded. Multiorgan failure, complications from procedures and infections often lead to premature death.[13][14]