Familial Adenomatous Polyposis

- Article Author:

- Stephanie Carr

- Article Editor:

- Anup Kasi

- Updated:

- 8/15/2020 11:51:11 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Familial Adenomatous Polyposis CME

- PubMed Link:

- Familial Adenomatous Polyposis

Introduction

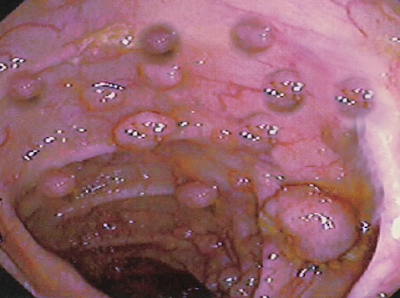

Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) or familial polyposis coli (FPC) is an autosomal dominant polyposis syndrome with varying degrees of penetrance. If untreated, patients will develop hundreds to thousands of polyps throughout the colon and rectum. Polyps often develop in the early teens and result in a nearly 100% lifetime risk of colorectal cancer by age forty if untreated. Colectomy is necessary for a substantial reduction in the risk of developing colorectal cancer. FAP also correlates with other malignancies, including gastric, duodenal, hepatoblastoma, and desmoid tumors.[1]

The underlying genetic defect in this disorder is a germline mutation in the APC gene. Over the years, it has been recognized that FAP has varied phenotypic expressions, including Gardner and Turcot syndromes.

Etiology

FAP results from a mutation at the APC gene on chromosome 5. The APC gene is a tumor suppressor gene. Most mutations are non-sense mutations, but the genotype and phenotypes vary significantly as the APC gene is large. The location of gene mutation contributes to the phenotypic variations, including the development of extracolonic manifestations of the disease.[2]

If more than ten adenomatous polyps present on a single colonoscopy, genetic testing is necessary. Ten to thirty percent of patients with a presentation of FAP will not have a detectable APC gene mutation.[1] Family members of patients without an identified mutation should still undergo the same surveillance as those with a detectable mutation.

Epidemiology

FAP occurs in 1 in 10000 individuals and is the second most common inherited colorectal cancer syndrome.[1] Overall, the syndrome is rare and contributes to only 1% of diagnosed colorectal cancer. About 30% of individuals with FAP have no known family history and represent de novo APC mutations.[3]

A milder form of the disease, attenuated familial adenomatous polyposis (AFAP), also contributes to colorectal cancer. These patients present at a later age with a lower polyp burden. Patients with AFAP have a 70% risk of developing CRC.[4] The treatment of FAP and AFAP requires surgical resection for a dramatic reduction in the risk of colorectal cancer.[1]

Pathophysiology

The APC gene functions as a tumor suppressor gene and plays a vital role in the alignment of chromosomes during metaphase. The normal APC protein promoted apoptosis in colonic epithelial cells. Mutations of the APC protein prevent apoptosis and allow for the uncontrolled growth of cells, leading to the development of adenomas.

History and Physical

The clinical presentation of familial adenomatous polyposis will vary based on family history. Patients with a known family history of FAP should begin screening at a young age with annual endoscopy evaluation. Individuals with no family history often present with colorectal cancer at a young age or during screening colonoscopy.

Most patients will present with nonspecific symptoms like diarrhea, abdominal discomfort, or rectal bleeding.

On physical exam, congenital hypertrophy of the retinal epithelium is specific for FAP. An ophthalmologist should perform an eye exam and may reveal flat, localized pigmented lesions of the retina. The patient usually has no visual complaints.

Some patients with Gardner syndrome may present with osteomas of the mandible or skull.

Abnormalities in dentition, including impacted teeth, supernumerary teeth, odontomas, and cysts, may be identified on a plain film X-ray.

In young children, there may be numerous epidermoid cysts on the face, extremities, and scalp.

Finally, some patients may have fibromas on the extremities, back, and trunk.

The diagnosis is the result of the visualization of more than 100 polyps on colonoscopy. FAP has a 100% lifetime risk of colorectal cancer if left untreated. There is also an increased risk of extra-colonic cancers.

Extracolonic Manifestations

Desmoid

Desmoid tumors are solid connective tissue tumors. The tumors are often benign but can grow very large and are locally invasive. They are very rare in the general population but occur in up to 10 to 15% of FAP patients with an increased incidence within the abdominal cavity. Individuals with a family history of desmoid tumors (DT) have a 25% risk of developing DTs. Females are twice as likely to develop DTs compared to males. Interestingly, surgical trauma is also related to an increased incidence of DTs. Therefore colectomy in FAP patients is deferred as long as possible in young patients.[5]

Desmoid tumors often present as a large, firm, painless mass. National Cancer Comprehensive Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend annual abdominal palpation with consideration of imaging in those with a significant family history of FAP and desmoid tumors. MRI imaging is most useful to determine the relationship to surrounding structures and evidence of local invasion. Most masses are ovoid or round in shape with irregular margins. Similar to the treatment of adenomas, sulindac and Celebrex have demonstrated stabilization or regression of DTs in nearly 30% of cases. Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) also demonstrate a positive effect against desmoid tumors.[5]

Gastric/Duodenal

Gastric polyps are present in approximately 90% of patients with FAP. Unlike colonic polyps, these polyps are unlikely to progress to adenocarcinoma. Only 1% of these patients will develop gastric cancer.[1] Upper endoscopy should begin at 20 to 25 years of age according to NCCN guidelines. These polyps should receive endoscopic treatment if possible, but polyps with high grade-dysplasia or malignant degeneration require surgical resection.

Hepatoblastoma

The increased incidence of hepatoblastoma in FAP patients is very low. It occurs most commonly in male children under the age of five. No universal screening recommendations exist. In children at high risk, screening would include liver ultrasound and alpha-fetoprotein levels every 3 to 6 months.[1]

Thyroid

Thyroid cancer occurs in approximately 2% of FAP patients with papillary carcinoma being the most common. There appears to be an increased incidence in the Hispanic population. There is a proven increased incidence in women as nearly 90% of thyroid cancers diagnosed in FAP patients are women.[1] Annual thyroid exams should begin in the teenage years with consideration for annual ultrasound screening.

Evaluation

Patients with known FAP or a strong family history FAP should undergo annual endoscopy evaluation with flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy starting at 10 to 12 years of age.[6] Surveillance should continue until the polyp load is unable to be controlled with endoscopic removal. Genetic testing is not a standard recommendation at an early age due to the psychological burden associated with positive results. Once a diagnosis of FAP is confirmed clinically, genetic testing should follow.

Treatment / Management

Definitive surgical management involves colectomy with or without proctectomy. Surgical options include subtotal colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis, subtotal colectomy with an ileostomy, or total proctocolectomy with ileoanal pouch.

Subtotal colectomy is a technically less challenging surgical technique but requires continued surveillance of the rectum. The rectal mucosa is still at high risk of developing adenocarcinoma. If the rectum is left intact, endoscopic surveillance must be performed every six months as the risk of developing rectal cancer is as high as 29% at 50 years of age.[2] Candidates for rectal sparing include those with a low polyp burden within the rectum, lack of advanced rectal neoplasia, and no evidence of CRC at the time of resection. For appropriately selected patients, the conversion to total proctocolectomy is near zero but increases to 35% in poorly surveillance candidates.

Total proctocolectomy (TPC) involves the removal of the colon and rectum with the creation of either an ileostomy or ileoanal pouch. Although no surveillance is required, there are disadvantages to this approach. TPC with ileoanal pouch can result in increased rates of infertility in men and women as well as urinary dysfunction. Although there is no difference in incontinence, there is an increase in stool urgency with an ileoanal pouch.[7]

Exploration of non-surgical treatment modalities in hopes of delaying surgical resection has had limited results. Sulindac is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory that has been shown in small studies to reduce the number of adenomas by nearly 50% and the size of adenomas by 65%. There was a recurrence of the adenomas with discontinuation of sulindac.[1] For patients with a retained rectum, sulindac is a therapeutic option to reduce the polyp burden within the rectum. The selective COX-2 inhibitor, celecoxib, has also been studied and, at high doses, has demonstrated a 30% reduction in adenoma burden.[2] Annual surveillance remains essential in patients with a retained rectum.

Differential Diagnosis

- Bannayan-relay-Ruvalcaba syndrome

- Cowden disease

- Cronkhite-Canada syndrome

- Hereditary nonpolyposis colon syndrome

- Hyperplastic polyposis

- Inflammatory polyposis

- Juvenile polyposis syndrome

- Lymphomatous polyposis

- MYH-associated polyposis

- Neurofibromatosis type 1

Prognosis

Untreated patients with FAP have a short life expectancy, with most dying in the 4th decade of life. Those who undergo colectomy can have improved survival. The most common cause of death is due to desmoid tumors and cancers of the gastrointestinal tract. Surveillance is the key to survival. Unfortunately, colectomy only addresses the problem in the colon. With advancing age, the risk of developing non-colorectal cancer increases significantly.

The desmoid tumors in FAP patients are often aggressive and tend to locally invade, leading to compression, obstruction, and blockage of blood vessels and nerves. The other malignancy that develops in FAP patients is adenocarcinoma of the duodenum and papilla of Vater.

Complications

Complications include the following:

- 100% of patients with develop colorectal cancer

- About 10% will develop duodenal or ampulla of Vater adenocarcinoma

- As many as 20% of patients will have desmoid tumors

- Other malignancies include hepatoblastoma, medulloblastoma, and many other cancers.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Multi-specialty management of familial adenomatous polyposis patients is essential to ensure appropriate screening and management of these complex patients. Team members should include a primary care provider, gastroenterologist, surgeon, otolaryngologist, and geneticist. Early endoscopic surveillance is essential to determine the appropriate timing of surgical resection. Although medical treatments can aid in the stabilization of the disease, the mainstay of FAP treatment is colectomy with or without proctectomy. Extra-colonic manifestations also require intensive screening recommendations with close clinical follow-up of FAP patients. With surveillance and surgical resection, patients with FAP can substantially reduce their risk of colorectal cancer and other associated malignancies.

(Click Image to Enlarge)