Foville Syndrome

- Article Author:

- Ossama Khazaal

- Article Author:

- Destiny Marquez

- Article Editor:

- Imama Naqvi

- Updated:

- 8/8/2020 8:16:55 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Foville Syndrome CME

- PubMed Link:

- Foville Syndrome

Introduction

Foville syndrome is a rare inferior medial pontine syndrome first characterized in 1858 by anatomist and psychiatrist Achille Louis Francois Foville. In his paper, “Notes on a Little-known Paralysis of Eye Muscles, and Its Relation to the Anatomy and Physiology of the Pons,” Foville posed a question: does the analysis of paralytic symptoms provide a basis for the exact localization of cerebral disease? He followed it with a description of a 43-year-old male who presented with unilateral conjugate horizontal gaze paralysis and facial nerve paralysis on the same side with crossed hemiparesis. Though several clinical variants have emerged over the years, classical Foville syndrome presents with ipsilateral sixth nerve palsy, facial palsy, and contralateral hemiparesis. Reports exist of other features such as facial hypoesthesia, peripheral deafness, Horner syndrome, ataxia, pain, and thermal hypoesthesia.[1][2][3]

Etiology

This clinical presentation is primarily the result of pontine infarction; however, other etiologies such as hemorrhage, granulomas, and tumors in the pons have been reported.[2] Isolated pontine infarcts comprise 3% of all ischemic strokes and are caused mainly by atheromatous branch occlusive disease. As atheromatous plaques develop in the endothelial lining of the basilar artery, they protrude into the perforator ostia, namely the paramedian pontine branches, causing occlusion and subsequent infarct.[4][5] Other possible causes are due to small vessel disease and cardioembolism.[6]

Epidemiology

Foville syndrome is a brainstem stroke syndrome with few reported cases worldwide. Classical Foville syndrome is similar to superior Foville syndrome, which likely refers to Raymond-Cestan syndrome. As such, it also has the appellation of inferior Foville syndrome.[2]

Pathophysiology

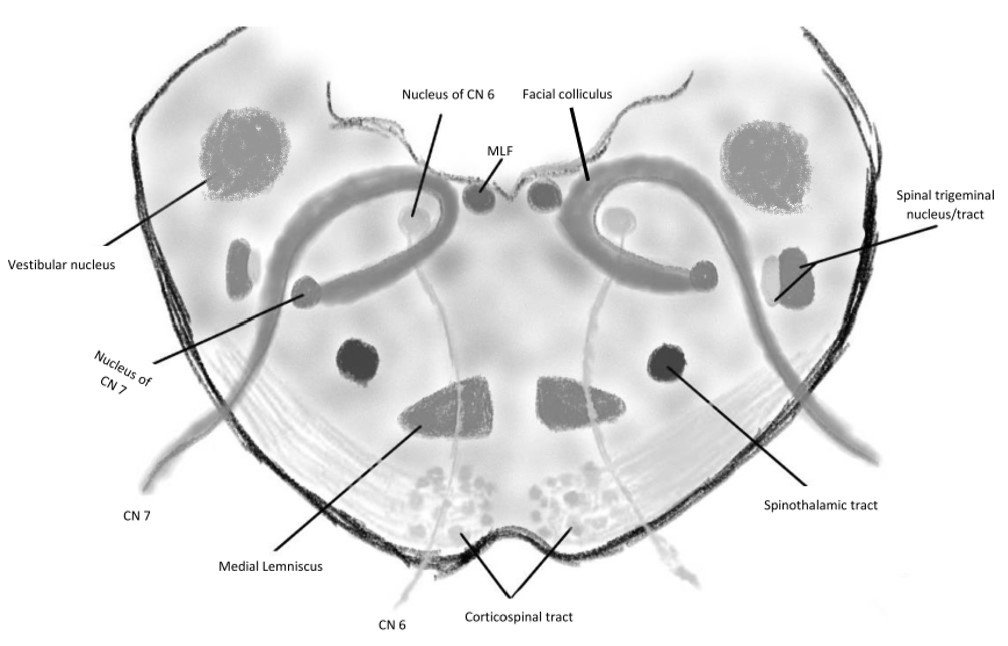

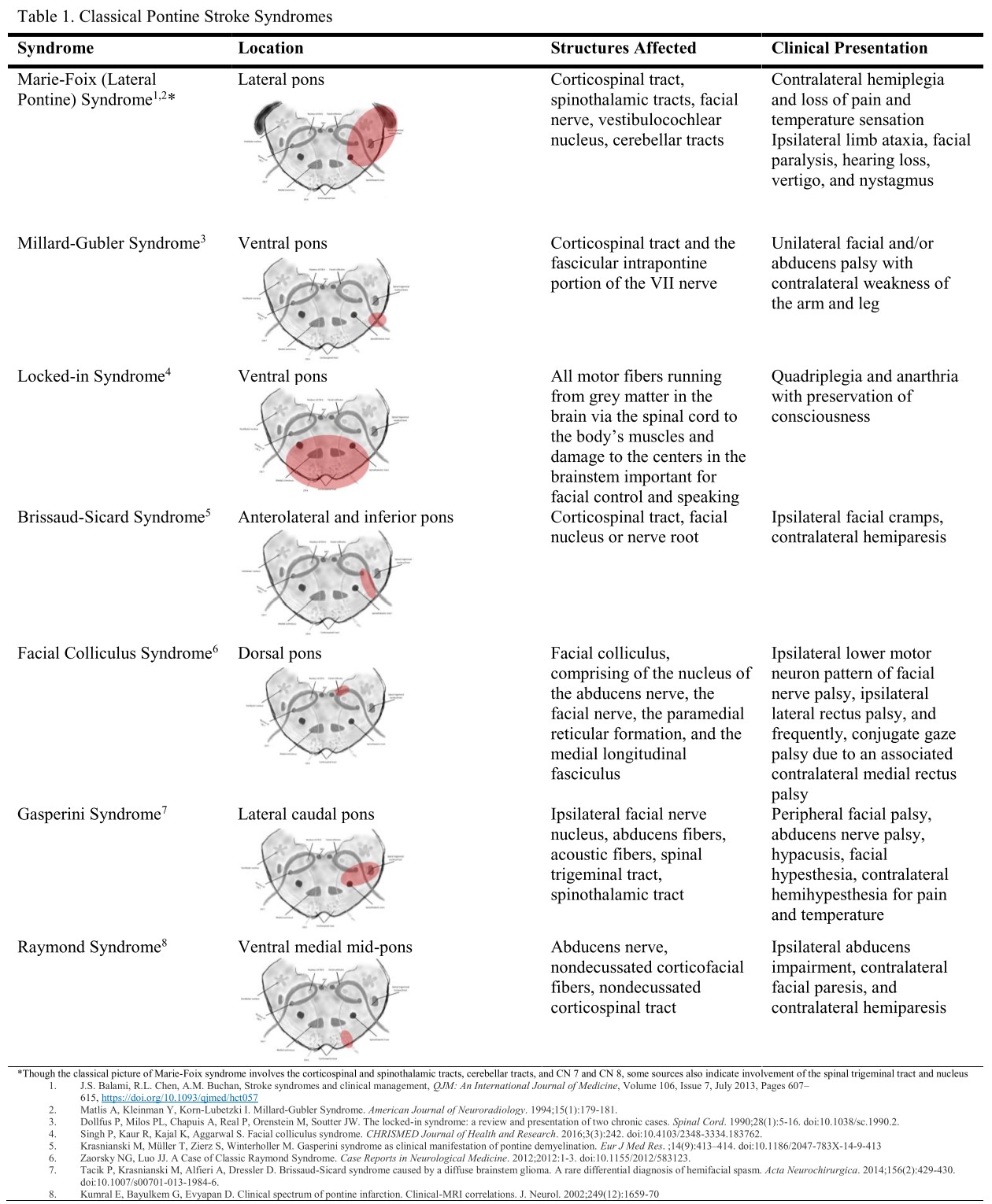

Foville syndrome is one of many stroke syndromes that localizes to the pons. Table 1 outlines additional pontine stroke syndromes regarding the location of infarction. Blood supply to the pons derives from branches of the vertebrobasilar system. After the formation of the basilar artery via the merging of vertebral arteries, smaller paramedian perforating branches of the basilar artery supply each side of the paramedian caudal pons, an area that has critical structures, affected in Foville syndrome.[4] Important nerve nuclei in the region of the pons include the trigeminal nerve sensory and motor nuclei, abducens nucleus, facial nerve nucleus, and vestibulocochlear nuclei. Structures affected that are critical to horizontal eye movement and gaze in this region are the paramedian pontine reticular formation (PPRF) and medial longitudinal fasciculus. Finally, a series of tracts, namely, the medial lemniscus, spinothalamic tract, and descending pyramidal tracts, traverse this region.

History and Physical

The clinical presentation of this syndrome is consistent with most brainstem stroke presentations – cranial nerve findings with crossed signs. There have been different clinical variants due to an array of possible lesions, and, as a result, there can be some phenotypic heterogeneity. The classic syndrome involves the inferiomedial pons which would present with ipsilateral sixth nerve palsy, seventh nerve palsy and/or eight nerve palsy, fifth sensory nuclear palsy, and long tract signs: contralateral hemiparesis and hemisensory loss. Other symptoms include ataxia and Horner syndrome due to the involvement of afferent white matter fibers heading to the middle cerebellar peduncle and sympathetic fibers, respectively.

The cranial nerve findings can present as follows:

- Sixth nuclear palsy: this presents as an inability to abduct the ipsilateral eye. With the involvement of the PPRF, this presents as a conjugate gaze palsy, meaning the inability to move the eyes towards the affected side; this becomes important here since conjugate gaze palsy can localize to more than one area in the neuroaxis. In this case, the eyes will classically not cross the midline with vestibulo-ocular reflex testing (VOR) due to nuclear involvement. On the other hand, if the conjugate gaze palsy is due to damage to the frontal eye fields to the midline is crossed with VOR testing.

- Seventh nerve palsy: this presents as a lower motor neuron ipsilateral facial weakness involving the upper and lower face.

- Eighth nuclear palsy: this presents with ipsilateral sensorineural hearing loss.

- Fifth nuclear palsy: this presents with ipsilateral loss of crude touch, pain, and temperature facial sensation due to the involvement of the spinal tract of V nucleus that runs caudally from the pons.

The long tract findings can present as follows:

- Corticospinal tracts: this presents with contralateral hemiplegia as these fibers are uncrossed yet at that level of the pons.

- Medial lemniscus: this presents with contralateral hemisensory loss (fine touch, vibration, and proprioception) as these fibers are ascending and crossed at this point.

- Descending sympathetic nerves: this can present as Horner’s Syndrome with ptosis, miosis, and anhidrosis ipsilateral to the lesion.

Afferent fibers through the middle cerebellar peduncles: this can present with ipsilateral appendicular ataxia. These corticopontocerebellar pathways are involved in the coordination and planning of movement.

Evaluation

In terms of etiology, there are three potential artery disease subtypes: large artery disease of the basilar artery, branch disease of the basilar artery, and small vessel disease. An MRI of the brain is necessary to evaluate for other brainstem structural etiologies such as intracranial hemorrhage, tumor, or inflammatory lesions. The vascular evaluation will help determine the etiologies discussed above. The area of the inferomedial pons receives vascular supply from the paramedian branches from the basilar artery and thus an MRI angiography or CT angiography, depending on availability and access, should be performed.[6][7] Additionally, a cardiac evaluation is warranted to rule out any sources of cardioembolism, especially if the vascular evaluation is unremarkable. Recommendations include assessment and screening for cardiovascular risk factors per the American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines.[8]

Treatment / Management

As discussed previously, there are various etiologies for this localization. However, the most common etiology is vascular disease, either small vessel or atheromatous branch occlusion. The mainstay treatment of lacunar strokes is antiplatelet therapy and control of vascular risk factors for secondary prevention. Antiplatelet and statin therapy should commence on admission. Control of hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and smoking cessation are as per the AHA/Stroke guidelines.[8] Patients should also undergo evaluation by physical therapists, occupational therapists, and PM&R physicians for post-acute stroke rehabilitation. Post-discharge follow up, and complications require attention in the outpatient setting.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes any structural lesion that can localize to the inferomedial area of the pons, which can include neoplastic processes, hemorrhages, inflammatory disorders, and vascular malformations such as AVM (arteriovenous malformation).

Prognosis

The evidence for long term outcomes has been a research topic in a few prospective studies. In a study by Zhao et al., 281 patients with pontine infarcts were studied for disability rates at one year. They found that the majority of patients with strokes involving the paramedian artery had a good prognosis (defined as a modified Rankin Score (mRS) less than 2).[9]

Complications

Medical complications reported after stroke include recurrent strokes, falls, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, chest and urinary tract infections, pain, pressure sores, and depression/anxiety.[10]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Antiplatelet and statin therapy should be initiated on admission. Control of hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and smoking cessation as per the AHA/stroke guidelines.[8]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Stroke is the fifth leading cause of death and the leading cause of serious long-term disability in the United States (US). The incidence of stroke continues to rise, driven by an aging population with 7 million stroke survivors currently in the US. The combined cost of stroke treatment and care is expected to double to $240.7 billion annually by 2030. Improvements in primary and secondary stroke prevention are necessary to reduce the current and projected economic burden of stroke. Stroke survivors have physical and cognitive impairments and complex medical and social needs that are unmet by the current fragmented system of outpatient stroke care. To improve outcomes, an interprofessional team dedicated to stroke patients is now the current standard of care.

Acute stroke treatment advances in intravenous thrombolytic therapy and endovascular capabilities have contributed to improvement in stroke outcomes. However, it largely remains a chronic condition with a limited evidence base for recovery measures.

Stroke rehabilitation provides a conduit after acute hospitalization to address residual functional deficits that a majority of stroke survivors suffer. AHA guidelines suggest rehabilitation programs with varying levels of care and interventions, management of comorbidities, and disability assessments.[11]

Outpatient stroke prevention clinics provide an opportunity to address transitions of care and provide patient-centered care for stroke survivors.

The primary care provider, pharmacist, and nurse practitioner should educate patients on the prevention of stroke by discontinuing smoking, adopting healthy eating habits, exercising regularly, maintaining healthy body weight, and being compliant with medications. Pharmacists are also tasked with medication reconciliation and verifying dosing, and reporting back to the healthcare team if they find anything that warrants attention. Nursing staff often has the first contact with a patient at each follow-up visit and can assess for progress and also any adverse medication effects. Physical and occupational therapists may also be involved and must report back to the managing clinician regarding progress and any setbacks. The entire interprofessional team needs to collaborate and communicate to drive outcomes effectively. [Level 5]

Fundamentally, enhancing post-stroke health outcomes rests heavily on an interprofessional effort consolidated by an interprofessional team that includes physicians with expertise in stroke and other health care providers that includes speech and physical therapy.