Free Tissue Transfer Of The Lateral Thigh And Anterolateral Thigh

- Article Author:

- Leon Alexander

- Article Editor:

- Matthew Fahrenkopf

- Updated:

- 9/25/2020 2:51:39 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Free Tissue Transfer Of The Lateral Thigh And Anterolateral Thigh CME

- PubMed Link:

- Free Tissue Transfer Of The Lateral Thigh And Anterolateral Thigh

Introduction

The anterolateral thigh flap (ALT), which was first described by Song (1984), is now well-established in reconstructive microsurgery as a workhorse flap. It is a versatile flap with many attributes that include long vascular pedicle with adequate vessel diameter, ability to harvest large areas of skin without added donor site morbidity, adaptability for use as a sensate flap, use as a flow-through flap for vascular gaps in the extremities, a two-team approach allows simultaneous flap harvest and resection/debridement of the recipient area, the flexibility of the flap to be folded or use of a double skin-paddle and its use as a chimeric flap to reconstruct composite soft tissue defects almost anywhere in the body. It can also be used for breast reconstruction if lower abdominal skin is unavailable due to previous scars or surgeries.[1][2]

The ALT flap is relatively easy to harvest if the principles of perforator dissection are followed. The vascularity of the flap is reliable even though there is some variability in its perforator anatomy.[3][4][5]

Anatomy and Physiology

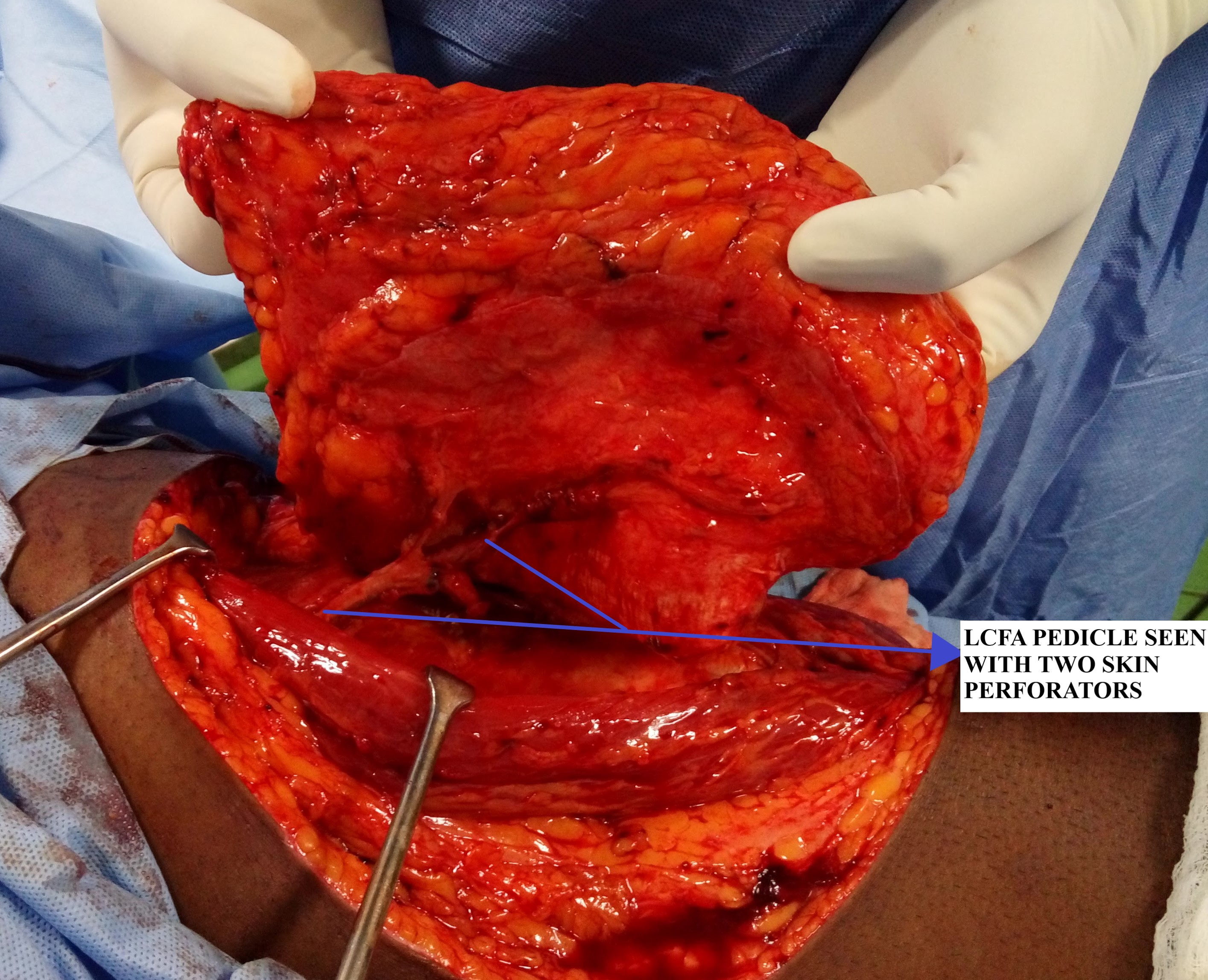

The anterolateral flap is classically described as a fasciocutaneous perforator flap based on the septocutaneous or musculocutaneous perforators (predominant) arising from the descending branch of the lateral circumflex femoral artery (LCFA), the largest branch of the profunda femoris system in the thigh. Earlier anatomical dissections described the ALT pedicle as predominantly septocutaneous perforators; however, recent research suggests the contrary. Now, it is well accepted that musculocutaneous perforators comprise the predominant blood supply (87%) to the flap.[3][4][5][6]

The vascular territory of the ALT flap extends from the anterior superior iliac spine superiorly to the lateral femoral condyle inferiorly and from the medial edge of the rectus femoris muscle anteriorly to the iliopubic tract posteriorly.

The LCFA, after arising from the profunda femoris artery, travels deep to the rectus femoris and divides into three branches that are ascending, transverse, and descending branches. The descending branch of LCFA travels along the medial edge of vastus lateralis in the intermuscular septum giving off perforators that supply the anterolateral thigh skin. The ALT flap provides a long pedicle (8 to 16 cm) with adequate vessel lumen size (2 to 2.5mm). The venous drainage of the flap is via two venae comitantes which accompany the arterial pedicle. The ALT flap can also be harvested as a sensate flap by including the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve in the flap design.[1][3][4][5][6]

Lateral Thigh Flap

The lateral thigh flap is a pedicle flap based on the LCFA, mainly the ascending and transverse branches (TFL perforator). They are classically described for the reconstruction of ischial and trochanteric pressure sores. It can also be based on the ALT perforator (descending branch of LCFA) and used for perineal and abdominal wall reconstruction as a pedicled flap.

Indications

The anterolateral flap is versatile and has a wide range of indications, including:

1. Head and Neck Reconstruction: following resection of head and neck tumors, the ALT flap can be used to resurface the defect either as a cover or as double skin paddle with cover and lining. A unique application of ALT flap is in esophageal reconstruction wherein it is folded onto itself (skin inside to form lumen) as a tubed flap.[1][7][8][9]

2. Secondary Burn Reconstruction: following sequelae of burn injuries like extensive scar contractures, e.g., ALT flap can be used following the release of extensive post-burn contracture (PBC) neck.[10]

3. Breast Reconstruction: It can also be used for breast reconstruction if lower abdominal skin is unavailable due to previous scars or surgeries (abdominoplasties, laparotomy) or salvage following primary breast reconstruction.[11][12]

4. Abdominal Wall Reconstruction: It can be used as a pedicled flap for lower abdominal reconstruction wherein it is harvested as a myocutaneous flap or a composite flap with fascia (tensor fascia lata). For more significant and extensive defects of the abdominal wall, free ALT transfer is preferred. It can include multiple tissue components like muscle and or fascia (fascia lata) using the chimeric flap principle.[13][14]

5. Upper and Lower Extremity Reconstruction: posttraumatic defects around the knee can be resurfaced using the distally based ALT flap. For defects involving the lower one-third and foot, a thinned ALT flap may be used. It can also be used as a flow-through flap for resurfacing defects in the lower limb while maintaining blood supply in an ischaemic leg. Similarly, it can be used for the extensive defects in the upper extremity. When tendon gliding is paramount, it can be harvested as a composite flap by including fascia lata to facilitate this.[15][16][17]

6. Perineum and penile reconstruction: a proximally based ALT flap can be used for perineal reconstruction. The free ALT flap has also been used in gender reassignment surgery (female to male) for phalloplasty.[18][19]

Contraindications

There are no absolute contraindications to the use of the anterolateral flap. The relative contraindications to its use include:

- Morbid obesity

- A severe peripheral occlusive arterial disease where the circulation to the flap may be unreliable

- Previous trauma or scarring of the anterolateral thigh skin

- Extensive medical co-morbidities (patient is unfit for long surgeries)[20]

Equipment

The equipment for flap harvest is the same as that for any free flap microsurgical case, pre-operatively sterile plastic sheet/drape to make a template of the defect, hand doppler, and skin markers for marking of perforators and flap marking. Intra-operatively surgeons will require loupes for flap dissection and operating microscope with good optics for microsurgical anastomosis.

Instruments for flap harvest include standard plastic surgical instruments like skin hooks, self-retaining retractors, Adson forceps, Debakey forceps, fine tenotomy scissors, ligaclips, skin dermatome, and mesher. Microsurgical instruments – jeweler forceps, Castroviejo needle holder, vessel dilator forceps, microscissors (both curved and straight), microvascular clamps (both arterial and venous clamps), and micro sutures (8-0, 9-0, and 10-0 nylon sutures).

Heparin saline solution, 1% or 2% plain xylocaine solution, and papaverine solution are required for intraoperative irrigation of vessels to prevent vasospasm. Post-operative dressing materials required include plaster of Paris (POP) slab, burn gauze, soft bandage & wool, elastic-crepe bandage, and sterile/antiseptic dressing.

Personnel

A two-team approach is usually feasible during the harvest of anterolateral flaps, depending on the case. If used in lower extremity reconstruction, the main surgeon can harvest the flap, simultaneously the junior surgeon or colleague can prepare the recipient bed, including exposure of the vessels for microvascular anastomosis. This approach entails two scrub nurses, one circulating nurse to monitor flap 'off and on' times and tourniquet times (if used). An anesthetist and the anesthesia technician is also required. Postoperatively the patient will require monitoring of the flap for at least 5-7 days by ward nurses trained in free flap monitoring.

Preparation

The flap harvest can be performed under general anesthesia with the patient in a supine position. The thickness of thigh skin is assessed preoperatively by doing a skin pinch test, which gives an idea of its suitability for primary closure or the requirement of a skin graft for the donor site. In patients with peripheral vascular disease, a CT angiogram can be done to assess the vascular flow to the limb and the availability of perforators.

Before starting the procedure, the hair of both thighs is clipped. A critical point to note is that foot and leg should be in a neutral position with both pointing towards the ceiling, which is mandatory for flap harvest, and rotation should be avoided at all costs.

Preoperative flap marking is done by drawing a line from the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) to the superolateral border of the patella, which is the axis of the flap and represents the septum between the rectus femoris and vastus lateralis. The midway point on this line is marked, and a circle with a 3 cm radius is drawn around it. Most perforators will be found in the outer, lower quadrant of this circle. Using a handheld doppler, the dominant cutaneous perforators are marked, and the flap is designed according to the defect size. The flap can be designed with perforators in a central position or in an eccentric position, which yields a longer pedicle length. Finally, prepping and draping is done in such a way to facilitate a two-team approach to simultaneous flap harvest and recipient site preparation.

Flap design and marking are done in such a way to facilitate longitudinal closure of the donor site, but if the recipient defect is significant, then flaps up to 35cm x 25cm can be harvested based on a single perforator.[1][2][21]

Technique

The anterolateral flap can be harvested as a skin flap (skin and subcutaneous tissue) using a subfascial dissection technique to yield thin or ultrathin flaps. It can also be harvested as a fasciocutaneous flap, which is the classically described technique and also the most commonly performed; it can be harvested as a musculocutaneous flap by including the vastus lateralis. It can also be harvested as a chimeric flap by adding various other tissues, each with its independent vascular supply (including rectus femoris, tensor fascia lata, or anteromedial thigh skin along with ALT skin).[1][2][6][21]

Step 1 - Flap and perforator dissection: Flap dissection can be done either in a suprafacial or subfascial plane depending on the defect. Generally, the subfascial dissection technique is more straightforward to identify the cutaneous perforators supplying the flap, more commonly performed, and allows the surgeon to map the perforator anatomy and tailor the flap accordingly.

The incision is made on the medial border of the flap down to the fascia. Once the subfascial plane is entered, the septum between the rectus femoris and vastus lateralis is identified as a yellow fat stripe. It represents the site where septocutaneous perforators may emerge. If no septocutaneous perforators are found, then dissection is carried out laterally in the subfascial plane to look for perforators (musculocutaneous) arising from the vastus lateralis. All potential perforators are identified, and one or two perforators with the excellent caliber and pulsatility are chosen, which will now be the primary supply to the flap.

Step 2 - Pedicle dissection and isolation: Once the perforator anatomy is confirmed, the rectus femoris is then retracted medially to expose the septum entirely and trace the course of LCFA. The next step involves tedious perforator dissection wherein the perforators are traced proximally by deroofing the vastus lateralis (musculocutaneous perforators) or a straightforward dissection in case of septocutaneous perforators. During this intramuscular perforator dissection, numerous small muscular branches will be encountered, especially on the lateral and posterior sides of the perforator, which will have to be ligated, and this proceeds until its take off from the descending branch of LCFA is reached. Alternatively, the muscle can be included with the flap, thereby avoiding this time-consuming and challenging step of perforator isolation. The motor nerve to vastus lateralis accompanies the descending branch of LCFA and must be preserved. Further proximal dissection of LCFA is carried out depending on the length of the pedicle required for anastomosis with the recipient's vessels. Another critical point to note in the proximal dissection is that the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve is usually found proximally along a line connecting ASIS to the superolateral patella border. This nerve must be preserved if not harvesting a sensory flap.

Step 3 - Flap modification/thining: When thin flaps are required for resurfacing certain areas like the dorsum of foot, hand defects, and neck defects, primary defatting can be performed. The flap pedicle must still be perfusing while performing the defatting to ensure that it does not compromise the flap viability. The defatting must progress from the deeper larger fat globule layer to the superficial smaller fat globule layer and must be uniformly done throughout, making sure to preserve adequate cuff of tissue around the pedicle (at least 2 cm thickness). Flap thinning is based on the preservation of subdermal plexus, which is nourished by perforators supplying the flap.

Step 4 - Pedicle division & Microvascular anastomosis: After adequate thinning of the flap, the next step is flap pedicle division, and the time is noted ('flap off' time noted). Then the flap is transferred to the defect and temporarily inset with few stay sutures. The microvascular anastomosis is done between the flap vessels and the recipient vessels using 9-0 or 10-0 nylon under the operating microscope. After completion of vessel anastomosis ('flap on' time noted), the adequacy of flow, any anastomotic site leaks should be checked. The flap perfusion and viability should also be confirmed by observing the color, warmth, bleeding from edges of the flap.

Step 5 - Flap inset: After confirmation of vessel flow and flap perfusion, the final inset of the flap is done. Suction drain or corrugated rubber drains are inserted beneath the flap. The site of the anastomosis is marked on the flap for postoperative monitoring. Dressings and POP slab are applied with a 'flap window' for postoperative flap monitoring. Tight compressive dressings are avoided.

Step 6 - Donor site closure: The donor site can be closed primarily, or if the donor defect is significant and primary closure is under excessive tension, a split skin graft (SSG) is applied over it. A vacuum dressing (VAC) can be applied over the donor site closure wound, especially if a skin graft is used, and it helps in the uptake of graft and preventing wound dehiscence in primary closure.

In cases when ALT perforators are absent or not of good caliber (2%), then there are four alternative options:

- Proximal dissection and exploration of the transverse branch of LCFA and harvest of the tensor fascia lata (TFL) perforator flap.

- Exploration of the rectus femoris branch (medial branch of descending LCFA) and raising of the anteromedial thigh flap (AMT).

- Elevation of a free vastus lateralis muscle flap.

- Explore in the contralateral thigh or abandon the procedure and look for alternative donor sites.[1][2][6][20][22][23][24]

Complications

The most dreaded complication following a free flap transfer is flap failure; hence the importance of postoperative flap monitoring. The causes of flap failure include:

- Arterial or venous insufficiency

- Thrombosis

- Venous congestion

- Twisting of the pedicle

- Compression of the pedicle

- Tension at flap edges leading to marginal flap loss

Other complications include:

- Color mismatch between flap and recipient site

- Excessive bulky flaps leading to fat necrosis

- Hematoma

- Seroma

- Infection

- Delayed wound healing

- Wound dehiscence

- Hypertrophic scarring of the donor site

- Failure of skin graft take over the donor site and sensory loss over the donor thigh.[25]

Clinical Significance

The success rate of anterolateral flaps are higher than 95%, and it has become the backbone of reconstructive microsurgery with broad indications for resurfacing defects from head to foot. The advantages of using the ALT flap include:

- Ease of harvest with reliable anatomy

- Long and large calibre vascular pedicle

- Versatility in flap modification like flap thinning or harvesting of chimeric flaps depending on the donor site requirement

- Ability to use as a sensate flap

- Little donor site morbidity

- The use of a two-team approach which decreases operating time[26][27]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The anterolateral flap has become an essential procedure in the plastic surgeon's armamentarium, and its widespread use involves a team approach wherein the plastic surgeon is called upon to help solve other specialties problems. It can be used to cover difficult open complex lower extremity fractures, which will involve the plastic surgeon, orthopedic surgeon, anesthetist, physical medicine specialist, and physiotherapist. This orthoplastic approach in extremity reconstruction involves the simultaneous application of the principles and practice of orthopedic and plastic surgery to enhance and optimize patient outcomes following limb reconstructive surgery.

Similarly, in head and neck reconstruction where a multidisciplinary team (MDT) approach is essential to prevent the locoregional and distant spread of tumors, the concept of wide local excision combined with immediate reconstruction with free flaps and adjuvant chemoradiation is gaining popularity. [Level 3]

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Monitoring

One of the most important aspects of the success of free flap surgery is a timely intervention in case of early complications, especially flap failure, and proper monitoring and good postoperative care is critical. The role of ward nurses and other allied staff is important to ensure that patients who undergo anterolateral free flap reconstructions have a good outcome. To ensure these goals are met, there should be a good understanding and coordination among the members of the plastic and reconstructive surgery team, with each person having a clear idea about their role, responsibilities, and their limitations.

Postoperative monitoring of ALT free flap is the most critical during the first 24 to 48 hours and should be carried out diligently until at least the first week after surgery. Proper free flap monitoring helps in salvaging a failing free flap as there is an inverse relationship between the onset of flap failure and clinical recognition. Hourly flap monitoring for clinical signs of viability or vascularity by nurses includes - color, warmth, capillary refill, handheld doppler signals from flap pedicle, signs of hematoma, bleeding, and checking for compression or pressure over the flap pedicle. During the initial 48 hours, hourly flap monitoring is mandatory. Once the danger period has passed, monitoring of flap every three to four hours for a few days should be sufficient.

(Click Image to Enlarge)