Gastrointestinal Bleeding

- Article Author:

- Alexander DiGregorio

- Article Editor:

- Heidi Alvey

- Updated:

- 8/24/2020 11:01:28 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Gastrointestinal Bleeding CME

- PubMed Link:

- Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Introduction

Gastrointestinal bleeding can fall into two broad categories: upper and lower sources of bleeding. The anatomic landmark that separates upper and lower bleeds is the ligament of Treitz, also known as the suspensory ligament of the duodenum. This peritoneal structure suspends the duodenojejunal flexure from the retroperitoneum. Bleeding that originates above the ligament of Treitz usually presents either as hematemesis or melena whereas bleeding that originates below most commonly presents as hematochezia. Hematemesis is the regurgitation of blood or blood mixed with stomach contents. Melena is dark, black, and tarry feces that typically has a strong characteristic odor caused by the digestive enzyme activity and intestinal bacteria on hemoglobin. Hematochezia is the passing of bright red blood via the rectum.

Etiology

Upper GI Bleeding

- Peptic ulcer disease (can be secondary to excess gastric acid, H. pylori infection, NSAID overuse, or physiologic stress)

- Esophagitis

- Gastritis and Duodenitis

- Varices

- Portal Hypertensive Gastropathy (PHG)

- Angiodysplasia

- Dieulafoy’s lesion (bleeding dilated vessel that erodes through the gastrointestinal epithelium but has no primary ulceration; can any location along the GI tract[1]

- Gastric Antral Valvular Ectasia (GAVE; also known as watermelon stomach)

- Mallory-Weiss tears

- Cameron lesions (bleeding ulcers occurring at the site of a hiatal hernia[2]

- Aortoenteric fistulas

- Foreign body ingestion

- Post-surgical bleeds (post-anastomotic bleeding, post-polypectomy bleeding, post-sphincterotomy bleeding)

- Upper GI tumors

- Hemobilia (bleeding from the biliary tract)

- Hemosuccus pancreaticus (bleeding from the pancreatic duct)

Lower GI Bleeding

- Diverticulosis (colonic wall protrusion at the site of penetrating vessels; over time mucosa overlying the vessel can be injured and rupture leading to bleeding) [diverticulosis]

- Angiodysplasia

- Infectious Colitis

- Ischemic Colitis

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- Colon cancer

- Hemorrhoids

- Anal fissures

- Rectal varices

- Dieulafoy’s lesion (more rarely found outside of the stomach, but can be found throughout GI tract)

- Radiation-induced damage following treatment of abdominal or pelvic cancers

- Post-surgical (post-polypectomy bleeding, post-biopsy bleeding)

Epidemiology

History and Physical

History

- Question patient for potential clues regarding:

- Previous episodes of GI bleeding

- Past medical history relevant to potential bleeding sources (e.g., varices, portal hypertension, alcohol abuse, tobacco abuse, ulcers, H. pylori, diverticulitis, hemorrhoids, IBD)

- Comorbid conditions that could affect management

- Contributory or confounding medications (NSAIDs, anticoagulants, antiplatelet agents, bismuth, iron)

- Symptoms associated with bleeding (e.g., painless vs. painful, trouble swallowing, unintentional weight loss, preceding emesis or retching, change in bowel habits)

Physical

- Look for signs of hemodynamic instability:

- Resting tachycardia — associated with the loss of less than 15% total blood volume

- Orthostatic Hypotension — carries an association with the loss of approximately 15% total blood volume

- Supine Hypotension — associated with the loss of approximately 40% total blood volume

- Abdominal pain may raise suspicion for perforation or ischemia.

- A rectal exam is important for the evaluation of:

- Anal fissures

- Hemorrhoids

- Anorectal mass

- Stool exam

Evaluation

Labs

- Complete blood count

- Hemoglobin/Hematocrit

- INR, PT, PTT

- Lactate

- Liver function tests

Diagnostic Studies

- Upper Endoscopy

- Can be diagnostic and therapeutic

- Allows visualization of the upper GI tract (typically including from the oral cavity up to the duodenum) and treatment with injection therapy, thermal coagulation, or hemostatic clips/bands

- Lower Endoscopy/Colonoscopy

- Can be diagnostic and therapeutic

- Allows visualization of the lower GI tract (including the colon and terminal ileum) and treatment with injection therapy, thermal coagulation, or hemostatic clips/bands

- Push Enteroscopy

- Allows further visualization of the small bowel

- Deep Small Bowel Enteroscopy

- Allows further visualization of the small bowel

- Nuclear Scintigraphy

- Tagged RBC scan

- Detects bleeding occurring at a rate of 0.1 to 0.5mL/min using technetium-99m (can only detect active bleeding[7]

- Can be helpful to localize angiographic and surgical interventions

- CT Angiography

- Allows for identification of an actively bleeding vessel

- Standard Angiography

- Meckel’s scan

- Nuclear medicine scan to look for ectopic gastric mucosa

Treatment / Management

Acute management of GI bleeding typically involves an assessment of the appropriate setting for treatment followed by resuscitation and supportive therapy while investigating the underlying cause and attempting to correct it.

Risk Stratification

Specific risk calculators attempt to help identify patients who would benefit from ICU level of care; most stratify based on mortality risk. The AIMS65 score and the Rockall Score calculate the mortality rate of upper GI bleeds. There are two separate Rockall scores; One is calculated before endoscopy and identifies pre-endoscopy mortality, whereas the second score is calculated post-endoscopy and calculates overall mortality and re-bleeding risks. The Oakland Score is a risk calculator that attempts to help calculate the probability of a safe discharge in lower GI bleeds.[10]

Setting

- ICU

- Patients with hemodynamic instability, continuous bleeding, or those with a significant risk of morbidity/mortality should undergo monitoring in an intensive care unit to facilitate more frequent observation of vital signs and more emergent therapeutic intervention.

- General Medical Ward

- Most other patients can undergo monitoring on a general medical floor. However, they would likely benefit from continuous telemetry monitoring for earlier recognition of hemodynamic compromise

- Outpatient

- Most patients with GI bleeding will require hospitalization. However, some young, healthy patients with self-limited and asymptomatic bleeding may be safely discharged and evaluated on an outpatient basis.

Treatments

- Nothing by mouth

- Provide supplemental oxygen if patient hypoxic (typically via nasal cannula, but patients with ongoing hematemesis or altered mental status may require intubation). Avoid NIPPV due to the risk of aspiration with ongoing vomiting.

- Adequate IV access - at least two large-bore peripheral IVs (18 gauge or larger) or a centrally placed cordis

- IV fluid resuscitation (with Normal Saline or Lactated Ringer’s solution)

- Type and Cross

- Transfusions

- Medications

- PPIs

- Used empirically for upper GI bleeds and can be continued or discontinued upon identification of the bleeding source

- Prokinetic Agents

- Given to improve visualization at the time of endoscopy

- Vasoactive medications

- Somatostatin and its analog octreotide can be used to treat variceal bleeding by inhibiting vasodilatory hormone release[13]

- Antibiotics

- Considered prophylactically in patients with cirrhosis to prevent translocation, especially from endoscopy

- Anticoagulant/antiplatelet agents

- Should be stopped if possible in acute bleeds

- Consider the reversal of agents on a case-by-case basis dependent on the severity of bleeding and risks of reversal

- PPIs

- Other

- Consider NGT lavage if necessary to remove fresh blood or clots to facilitate endoscopy

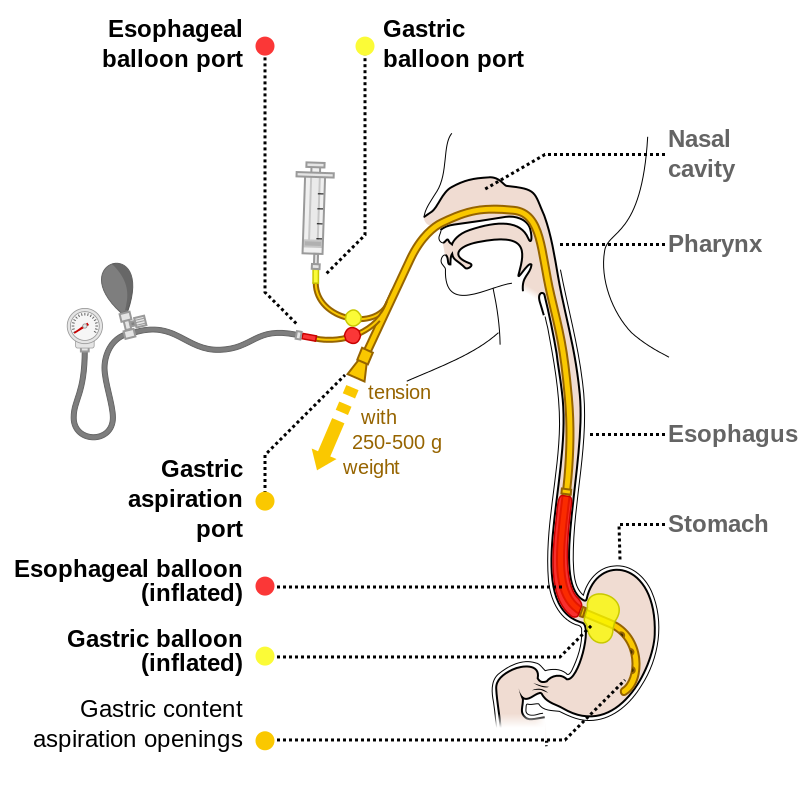

- Placement of a Blakemore or Minnesota tube should be considered in patients with hemodynamic instability/massive GI bleeds in the setting of known varices, which should be done only once the airway is secured. This procedure carries a significant complication risk (including arrhythmias, gastric or esophageal perforation) and should only be done by an experienced provider as a temporizing measure.

- Surgery should be consulted promptly in patients with massive bleeding or hemodynamic instability who have bleeding that is not amenable to any other treatment

Differential Diagnosis

Few diagnoses mimic GI bleeding. Occasionally, hemoptysis may be confused for hematemesis or vice versa. Ingestion of bismuth-containing products or iron supplements may cause stools to appear melanic. Certain foods/dyes may turn emesis or stool red, purple, or maroon (such as beets).

Prognosis

Limited studies exist regarding the prognosis following GI bleeding.

For upper GI bleeds, in-hospital mortality rates are approximately 10% based on observational studies. This rate holds steady up to 1-month post-hospitalization for GI bleed. Long-term follow-up of patients with UGIB shows that at three years after admission mortality rates from all causes approach 37%.

Mortality rates were higher in women than in men when adjusted for age, which differs from that of lower GI bleeding. Patients with multiple hospitalizations for GI bleeding carry higher mortality rates. Long-term prognosis was worst in patients who suffered from malignancies and variceal bleeds. The prognosis was worse with advancing age.[14]

For lower GI bleeds, all-cause in-hospital mortality is low—less than 4%. Death from LGIB itself is rare, with most in-hospital mortality occurring from other comorbid conditions. Increased risk of death corresponded to increasing age (as seen in cases of UGIB as well), comorbid conditions, and intestinal ischemia. Other negative prognostic factors include secondary bleeding (onset of bleed after being hospitalized for a different condition), patients with pre-existing coagulopathies, hypovolemia, transfusion requirement, and male sex. Not surprisingly, the lowest risks of mortality are associated with more benign causes of LGIB such as hemorrhoids, anal fissures, and colon polyps.[15] Long-term follow-up studies in patients with LGIB are not common.

Complications

- Respiratory Distress

- Myocardial Infarction

- Infection

- Shock

- Death

Consultations

- Gastroenterology

- Critical Care

- General Surgery

- Interventional Radiology

Deterrence and Patient Education

A GI bleed is any bleeding occurring from the gastrointestinal system. This includes the esophagus, stomach, small intestine, and large intestine (also known as the colon). Bleeding from the GI system can come from the upper GI tract (esophagus, stomach, and part of the small intestine) or the lower GI tract (second part of the small intestine and the large intestine). Some symptoms of GI bleeding are obvious, such as vomiting bright red blood or blood that looks like coffee-grounds or seeing bright red blood in the toilet with bowel movements. Some symptoms of GI bleeding are more subtle, such as dark or tar-like stools, belly pain, diarrhea, anemia (which is a low red blood cell count), weakness, lightheadedness, shortness of breath, pale skin, or a racing heart. There are many causes of bleeding from the GI tract. The doctor may perform a series of tests to evaluate concerns of a gastrointestinal bleed. Some of these tests check the blood for cell counts and clotting ability. Some tests include imaging to try to see from where the blood is coming.

Some tests are relatively invasive compared to others but allow for direct observation of the GI tract, such as an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) or a colonoscopy. In these procedures, the doctor gives medication to relax the patient and inserts a flexible scope with a light and camera from the mouth or the anus to observe the parts of the GI system it concerns them is bleeding. If there is bleeding, treatment may commence with oxygen, fluids through an IV, blood transfusions, or various medications to help stop the bleeding, reduce acid production, or empty the stomach. Patients can help avoid some causes of GI bleeding by not taking certain medications including NSAIDs (such as ibuprofen or naproxen) and receiving treatment for stomach ulcers or liver disease.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Care of patients with gastrointestinal bleeding requires coordinated and efficient interprofessional cooperation. Nurses manage the frequent monitoring of vital signs and more short-term interaction with and observation of patients. They must communicate their findings with the physicians, who use their own and nursing observations to make decisions for treatment. Multiple physicians may be necessary for treatment. General internists are typically responsible for the routine care of patients with GI bleeds. Critical care physicians may be involved if the patient warrants ICU level care for severe hemorrhages. Gastroenterologists perform endoscopic examinations and treatment if able during those procedures. Radiologists will interpret various imaging modalities and conveying those results to the providers. Interventional radiologists may perform diagnostic procedures, with the ability to also perform therapeutic modalities such as angiography-guided embolization. In some severe cases, general surgeons may be involved for intervention or exploratory procedures. Pharmacists are essential for providing oversight of medications used in the setting of bleeds and ensuring the use of proper dosages. A coordinated effort by all of these healthcare professionals functioning as an interprofessional team is necessary for early recognition and intervention in gastrointestinal bleeds to prevent further morbidity or mortalities.