Granuloma Inguinale

- Article Author:

- Jenna Santiago-Wickey

- Article Editor:

- Brianna Crosby

- Updated:

- 8/10/2020 10:53:15 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Granuloma Inguinale CME

- PubMed Link:

- Granuloma Inguinale

Introduction

Donovanosis or “granuloma inguinale” is a bacterial infection of the genital region. It is chronic and progressive. Genital ulcers attributed to donovanosis were first described in India by McLeod, and the causative agent was identified by Donovan, who also described Donovan bodies.[1]

Etiology

The bacteria that causes donovanosis is known as Klebsiella granulomatis comb. nov., but there has been significant debate over the most appropriate nomenclature. The causative agent of donovanosis was originally named Calymmatobacterium granulomatis by Aragao and Vianna in Brazil. After the original naming, it was found to have similarities to other Klebsiella species in respect to testing, structural aspects, and histologic appearance. Carter et al. reclassified this bacteria in 1999 from Calymmatobaacterium to Klebsiella based on genes 16 SrRNA and phoE. K. granulomatis is a gram-negative coccobacillus. It is intracellular and encapsulated. It has been demonstrated to function as a facultative aerobe. The first effective treatment used was emetic tartar in Brazil. The first successful culture was in the mid-1990s by using peripheral blood monocytes and human epithelial cell lines.[2]

Epidemiology

The transmission of donovanosis has been debated due to its apparent association with sexual contact despite reports of infection without sexual contact history. As of 1947, it has generally been accepted as a sexually transmitted infection based on a literature review done at the time. There is usually a history of sexual exposure before the lesion develops. There are also high rates of infection among age groups with increased sexual activity. Donovanosis has been diagnosed in women with lesions primarily located on the cervix, and men who have sex with men have a higher incidence of anal lesions. [3]A piece of evidence that tends to point away from donovanosis as a sexually transmitted infection is the low rates of sex workers affected. Also, there have been some cases of fecal transmission and children infected in nonsexual ways. There are case reports of children infected by sitting on adult’s laps and neonates infected during vaginal delivery. Some other risk factors are poor hygiene and low socioeconomic status. Also, the rate of transmission is thought to be low in general.[2]

Govender et al. reported 2 cases where young children were diagnosed with donovanosis with no history of sexual exposure. An 8-month-old female presented with a right ear mass and discharge. She was initially treated with antibiotics and surgical resection but did not follow up for 8 months. When she presented again, she was found to have progressed in symptomatology and had a new right temporal lobe abscess. She required a craniectomy to drain the abscess as well as a mastoidectomy. Tissue was removed during the surgery for analysis, and the diagnosis of granuloma inguinale was made. Questioning of the parents revealed no signs or symptoms of sexual abuse. No gynecological exam was performed on the patient’s mother, so it is unknown if she had a genital ulcer. The patient was treated with erythromycin with noted improvement in the right temporal lobe lesion noted on computed tomography prior to discharge. The patient and her family were unavailable for follow up after discharge. [2]

Another case of a 5-month-old male with left ear discharge was also described. In addition to discharge from the ear, he also had a lower motor neuron cranial nerve VII palsy, mass at the external auditory meatus, and a friable retroauricular abscess. Tissue samples obtained during the surgical resection of the mass revealed granuloma inguinale. Gynecological exam of the mother showed a cervical lesion confirmed to by granuloma inguinale histologically. Again, there were no signs of sexual abuse in this case. There are no documented cases of granuloma inguinale in children in the United States. The cases that have been reported in other locals have mostly been children 1 to 4 years of age. The incubation period of donovanosis is uncertain but estimated to be around 50 days based on human experimental infections. In general, the incubation period is recorded as 1 to 365 days due to lack of data.[4]

Pathophysiology

Donovanosis is a sexually transmitted infection that can rarely have non-sexual modes of transmission. It is classically associated with genital ulcers that demonstrate Donovan bodies on tissue smear samples.[3]

Histopathology

Histological evaluation is essential for the diagnosis of donovanosis. Donovan bodies are seen within large, mononuclear (Pund) cells as gram-negative intracytoplasmic cysts filled with deeply staining bodies. They can have a characteristic “safety pin” appearance. When these cyst structures rupture, they release infectious organisms. To obtain a sample for smear, first, clean the lesion with a dry cotton swab. Using saline before obtaining the swab may lead to an insufficient sample. Take great care not to disrupt any of the small blood vessels to minimize bleeding. The donovanosis swab should always be obtained before other testing to maximize tissue collections. An alternative method of tissue sampling is with either forceps or scalpel to obtain granulation tissue. The granulation tissue is then crushed between two slides to obtain a smear.[3] O’Farrell et al. used the RapiDiff and May Grunewald Giemsa techniques in 1988 in South Africa for the identification of Donovan bodies. Both stains allowed for visualization of the Donovan bodies in the same 23 of the 55 patients evaluated but RapiDiff was found to be superior due to a simpler procedure and less time to perform.[5]

History and Physical

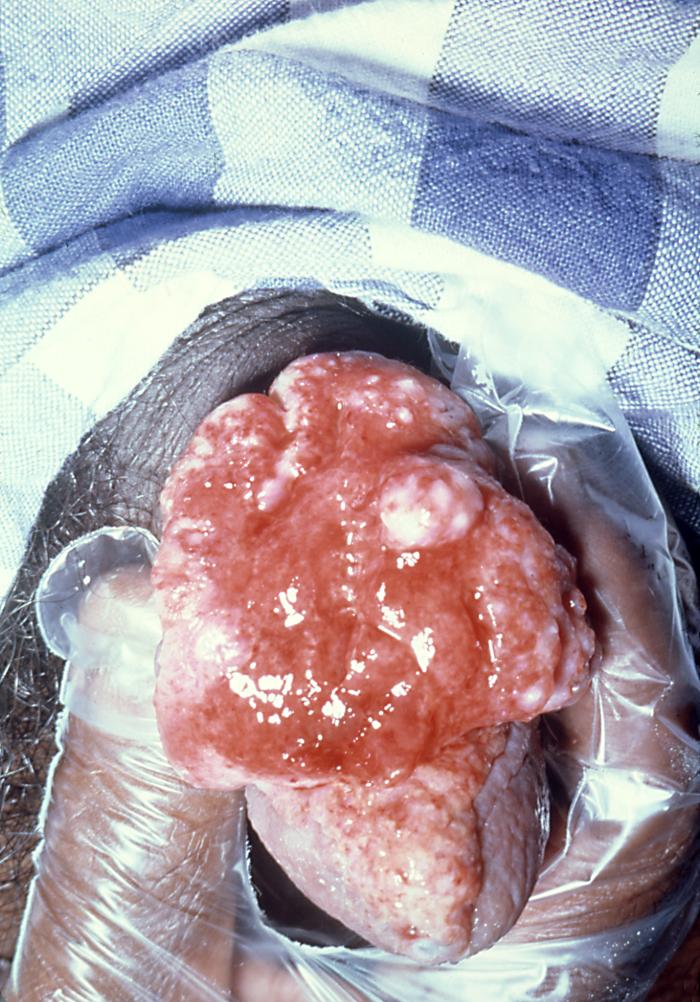

Donovanosis lesions usually start as a painless papule or subcutaneous nodule. The lesions develop the classic “beefy-red” appearance due to their high vascularity. The initial lesion takes on an ulcerative morphology after minor trauma. There is usually no regional lymphadenopathy. Developing subcutaneous granulomas known as pseudobuboes is possible. The lesions are progressive in an outward direction from the center. The borders of the lesions are sometimes described as “snake-like” in appearance. Self-inoculation is possible and may create mirror-image lesions in the same general location, usually across skin folds.[2] Patients often delayed seeking health care for many reasons, and therefore, they usually present with a more progressed lesion.[6] There are 4 types of lesions. Classic ulcerogranulomatous lesions are the most common with beefy-red, non-tender ulcers that bleed easily. The second type is hypertrophic or verrucous with irregular raise edges and dry texture. The third type is necrotic, offensive-smelling, deep ulceration that causes tissue destruction. The last type is sclerotic or cicatricial with fibrous and scar tissue. The genitals are affected in 90% of cases and the inguinal region in 10% of cases. The most common sites where men are affected are the prepuce, coronal sulcus, frenum, glans, and anus. The most common sites where women are affected are the labia minora, fourchette, cervix, and upper genital tract. Pregnant patients experience quicker progression of donovanosis lesions and respond slower to treatment compared to the general population. Extragenital lesions occur on the lips, gums, cheek, palate, pharynx, larynx, and chest 6% of the time.[3]

Evaluation

Diagnosis can be made by an experienced physician in endemic areas but may be difficult in other areas of the world. In nonendemic areas, the diagnosis will require a high index of suspicion. The diagnosis is confirmed by identifying Donovan bodies in a tissue smear. PCR testing is possible but is not widely available. It is seen in the research setting and often used during eradication programs. There are serologic tests that can be used for population studies, but they are not accurate enough to diagnose an individual.[3][2]

Treatment / Management

The CDC recommends that treatment should last until all lesions are healed. First-line treatment is azithromycin 1 g followed by 500 mg daily. Relapses can occur 6 to 18 months after seemingly successful treatment. Some alternative treatment regimens are doxycycline 100 mg twice per day, ciprofloxacin 750 mg twice per day, erythromycin 500 mg 4 times per day, and sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim twice per day. Patients that are slow to respond can also be given gentamicin 500 mg every 8 hours. Erythromycin is the medication of choice in pregnancy. There is no change in the recommendations for HIV positive patients. The 2016 European Guidelines for donovanosis treatment state that antibiotics should continue for a minimum of three weeks and until symptom resolution. They also recommend azithromycin as a first-line treatment that can be given as 1 g initially then 500 mg daily or 1 g weekly. Children should be given azithromycin 20 mg/kg for a disease treatment course or prophylaxis for 3 days if exposed during birth. The first study to demonstrate the effectiveness of azithromycin was performed by Bowden et al. between June 1994 and March 1995 in Australia. Seven patients received 1 g azithromycin weekly for 4 weeks, and 4 patients received 500 mg azithromycin daily for 7 days. After 6 weeks, 3 patients from the first regimen and 1 patient from the second were healed, and all other participants in the study were significantly improved. Azithromycin was shown to be effective against donovanosis and has the added benefit of short, intermittent dosing, which may facilitate treating endemic populations. Medication alone may be the only treatment required. Surgery may be needed for extensive tissue destruction. Patients require consistent monitoring for disease resolution and possible recurrence.[3][1]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for genital ulcers is broad and includes primary syphilis, secondary syphilis (condylomata lata), chancroid, lymphogranuloma venereum, genital herpes, neoplasm, amoebiasis, and several others. The possibility of a coinfection should always be considered since the risk factors for several of these diseases are similar. Lesions that have a more destructive appearance should be evaluated for carcinoma in addition to other causes. Also, pseudo-elephantiasis, which is a possible complication of donovanosis, can mimic lymphogranuloma venereum. Additionally, women with cervical lesions should also undergo testing for carcinoma and tuberculosis. If the diagnosis of donovanosis is confirmed, the patient should undergo HIV testing due to being at increased risk of transmission with donovanosis lesions. Any patient found to have a sexually transmitted disease should be considered for HIV testing.[3]

Prognosis

The prognosis for uncomplicated donovanosis is positive with appropriate treatment. There is the possibility of relapse, which can occur even after symptoms appear to have resolved. Lack of improvement should prompt further investigation and testing for co-infection or alternative diagnoses. If left untreated, there can be significant scarring and tissue destruction. Malignant transformation is also possible.[3]

Complications

Possible complications include neoplastic change, pseudo-elephantiasis, hematogenous spread, polyarthritis, osteomyelitis, vaginal bleeding, and stenosis of the urethra, vaginal, or anus. Dissemination into the abdominal cavity is a rare possible complication. Symptoms include fever, malaise, anemia, night sweats, weight loss, and sepsis. Also, many patients receiving care after having endured the disease process for a significant amount of time may have suffered emotionally. The lesions can be embarrassing and distressing to the patient. Always consider mental health disorders such as anxiety or depression and include suicide screening in these patients. [3]Murugan et al. described some cases of significant vaginal bleeding caused by donovanosis. A 33-year-old woman from Madurai presented to Rajaji Hospital after complaining of white vaginal discharged and prolonged menstrual periods. She was found to have ulcers of the cervix and vaginal vault with areas of necrosis. Donovan bodies were found in the ulcer smears. She was initially treated with streptomycin then switched to tetracycline when she could not tolerate the side effects of the first medication. She was noted to have significant improvement with decreased ulcer size and less discharge after 20 days of treatment. Two months after treatment she reported complete resolution of her symptoms and was noted to be symptom-free after 1 year. A 19-year-old woman also from Madurai presented to Rajaji Hospital with an antepartum hemorrhage at 24 weeks gestation. She was found to have a granulomatous cauliflower-like ulcerative growth in the vaginal vault. Smears of the ulcer showed Donovan Bodies. She was successfully treated with streptomycin with an almost complete resolution of her symptoms after one month.[7] Thappa et al. described a case of malignant transformation. A 25-year-old man from India presented with a lesion over the glans penis for four years duration. Donovan Bodies were seen on the tissue smear. However, he failed treatment with co-trimoxazole and azithromycin. A biopsy revealed squamous cell carcinoma.[8]

Pearls and Other Issues

Control and Prevention

The incidence of donovanosis has been decreasing worldwide most likely due to the realized role in HIV transmission. There have been multiple programs in the United States, Australia, and Papua New Guinea that have reduced disease prevalence. One program in Papua New Guinea involved mandatory inpatient treatment and utilized security guards in the wards to ensure completion of treatment.[3] Efforts in Australia have almost eradicated the disease. In the mid-1990s, a proactive approach to disease eradication was initiated. There were 115 cases of donovanosis noted within the aboriginal population in 1995. The Tri-State HIV/STI initiative implemented a Donovanosis Project Officer in 1997 to manage surveillance, diagnosis, and treatment. The prevalence significantly decreased over the following 3 years. In 2001, the National Donovanosis Eradication Committee was established after several organizations noted disease eradication was a worthy goal and possible. Both government and nongovernment agencies were involved, and they implemented a multidisciplinary approach. The goal of eradication was changed to elimination after realizing that eradication would require a global initiative. Elimination was defined as no new cases reported to the National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System (NNDSS) for 3 years. This second initiative utilized four Project Officers. As of 2004, there were only 5 reported cases of donovanosis.[9] Donovanosis has been targeted for eradication due to the risk of HIV transmission with genital ulcer disease. O’Farrell looked at STD clinics in Durban, South Africa and found higher rates of HIV-1 positivity in men with donovanosis as the duration of the lesions presence increased. There was a 5000-fold increase in the positive HIV-1 rates in men with donovanosis versus men with gonorrhea for greater than 3 months. Men with donovanosis are considered “super-spreaders” in regards to spreading HIV if they have the disease or acquiring the disease if they have genital lesions.[6] Since the incubation period is uncertain but estimated to be around 50 days, the CDC recommends treating anyone who has sexual contact with someone diagnosed with donovanosis within 60 days. It is unclear at this time if prophylaxis is useful in this setting. The 2016 European Guidelines also recommend prophylaxis for neonates exposed during vaginal birth.[1]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The nurse practitioner, primary care provider or the emergency department physician is unlikely to encounter donovanosis in the emergency department in the United States. Physicians will need to have a high index of suspicion based on travel history, social history, and physical exam. A broad differential diagnosis list is important when genital ulcers are present and sexually transmitted infection is suspected. Consider a pelvic exam on all women to evaluate for the presence of cervical lesions. All women of childbearing age should have a pregnancy test done in the emergency department. If donovanosis is suspected, it is important to recognize the extended course of treatment that may be required. It is reasonable to initiate treatment in the emergency department while arranging for proper follow-up testing and care.

Since donovanosis is so rare in the United States, patients should be referred to an infectious disease specialist or a clinician with experience in treating this condition. Definitive diagnosis in the emergency department is unlikely and can be pursued by a qualified specialist. It is important to prepare the patient for a prolonged treatment course and stress the importance of extended follow up to evaluate for reoccurrence. All patients presenting with possible donovanosis or sexually transmitted infection should be considered for HIV testing.

The pharmacist should educate the patient that the treatment is often for many months and if compliance is not maintained, the risk of relapse is high.