Hallux Rigidus

- Article Author:

- Jay Patel

- Article Editor:

- Michael Swords

- Updated:

- 9/20/2020 9:44:04 AM

- For CME on this topic:

- Hallux Rigidus CME

- PubMed Link:

- Hallux Rigidus

Introduction

Hallux rigidus is a condition that refers to degenerative arthritis of the first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint. Davies-Colley first described the condition in 1887, who coined the term as hallux flexus due to the plantar-flexed position of the proximal phalanx relative to the metatarsal head. Cotterill later described the term hallux rigidus to characterize the painful limitation of motion of the first MTP joint. The condition is associated with restriction of dorsiflexion. To emphasize the importance of the first MTP joint, approximately 119% of body weight is carried by it during the gait cycle with each step. In the early stages, the first MTP joint goes through osteophyte formation and degeneration of cartilage; this can progress to involve the entirety of the first MTP joint in the late stages.[1][2][3]

Etiology

Multiple other mechanisms and risk factors have been proposed to explain the pathology of hallux rigidus. Repetitive stress or inflammatory conditions such as gout, rheumatoid arthritis, metabolic conditions, damage to the MTP joint articular surface due to osteochondritis dissecans, and structural factors.[3]

Epidemiology

Hallux rigidus is the second most common condition affecting the first MTP joint after hallux valgus. It affects about 2.5% of people over the age of 50. Females are twice as likely than men to suffer from the hallux rigidus. The condition can occur in adolescence but uncommon. It is associated with osteochondritic lesion when present in the adolescent patient.[1][2][3]

Pathophysiology

The majority of cases of hallux rigidus are idiopathic. However, multiple authors have noted an association with the development of arthritis changes through both traumatic and iatrogenic causes. The underlying cause is likely multifactorial. Bilateral involvement is more common and is associated with family history and the female gender. Up to two-thirds of patients have a family history of hallux valgus. Achilles contracture, shoe wear, and an elevated metatarsal head do not appear to contribute to the development of first MTP joint arthritis.[3][4][5]

History and Physical

Presentation

- Presenting symptoms include pain, altered gait, and increased bulk of joints leading to difficulty with shoe wear. The compression of the dorsal medial cutaneous nerve may lead to numbness along the medial border of the great toe.

Physical Exam

- The first MTP joint is often swollen and tender and may have palpable dorsal osteophytes.

- There is a decrease in passive and active range of motion (ROM), most commonly in dorsiflexion. The pain usually occurs at terminal ROM with milder diseases; however, pain occurring in midrange motion may indicate a more severe arthritic disease due to more global articular wear to the metatarsal head.

- There is the reproduction of pain with forced dorsiflexion and might be a positive grind test.[2][3]

Evaluation

Radiographic Evaluation

- Weightbearing AP, lateral, and oblique views are necessary. MRI and CT scans are not a requirement for the diagnosis or treatment planning of the disease. The determination extent of joint space narrowing is best from an oblique radiograph.[3][2]

Classification

- Coughlin and Shurnas proposed this classification based on clinical and radiographic findings of the disease. The Coughlin and Shurnas Clinical Radiographic System for Grading Hallux Rigidus is as follows:

Grade 0

- Dorsiflexion: 40 to 60 degree and/or 10% to 20% loss compared to normal side

- Radiographic findings: normal

- Clinical Findings: No pain; only stiffness and loss of motion on physical examination

Grade 1

- Dorsiflexion: 30 to 40 degrees and/or 20% to 50% loss compared to the normal side

- Radiographic findings: Dorsal osteophyte is the main finding. Minimal joint space narrowing, periarticular sclerosis, and flattening of the metatarsal head

- Clinical findings: Mild pain and stiffness, pain at extremes of dorsiflexion and/or plantar flexion on examination.

Grade 2

- Dorsiflexion: 10 to 30 degree and/or 50% to 75% loss compared to normal side

- Radiographic findings: Dorsal, lateral, and possibly medial osteophytes giving a flattened appearance to metatarsal head, no more than 1/4 of dorsal joint space involved on the lateral radiograph; mild to moderate joint space narrowing and sclerosis, sesamoids not usually involved.

- Clinical findings: Moderate to severe pain and stiffness that may be constant; pain occurs just before maximum dorsiflexion and maximum plantarflexion on examination

Grade 3

- Dorsiflexion: 10 degrees or less and/or 75% to 100% loss compared with the normal side. There is a notable loss of metatarsophalangeal plantarflexion as well.

- Radiographic findings: Same as grade 2 but with substantial narrowing, possibly periarticular cystic changes, more than 1/4 of dorsal joint space involved on the lateral radiograph, sesamoids enlarged and/or cystic and/or irregular

- Clinical findings: Nearly constant pain and substantial stiffness at extremes of the range of motion but not at mid-range

Grade 4

Treatment / Management

Treatment & management

- Nonoperative

- NSAIDs can help reduce swelling and joint pain. Intraarticular steroid injections can provide temporary relief but have not shown long term benefits. Activity modifications such as avoiding running, jumping, and stairs can make a difference in pain and discomfort; however, it may not be desirable for many patients. Other conservative treatments include shoe modifications and orthotics. They aim to modify the biomechanics of the first MTP joint, reducing motion, limiting irritation from the dorsal osteophytes, and reducing the mechanical stresses on the joint. Morton's extension, made of a firm or rigid orthotic material that extends under the great toe, can help reduce dorsiflexion. Navicular pads have been used to alter the loading patterns of the joint. Rocker bottom soles can help diminish painful dorsiflexion during the gait cycle. Shoes with a high toe box can take the pressure off prominent osteophytes. However, many of these modifications are not well tolerated by patients.[1][2][3][8]

- Operative

- Cheilectomy

- This procedure has a good outcome with a mild to moderate degree of restriction in dorsiflexion with a satisfaction rate of 88% to 95%. Patients with more severe disease or pain during the midrange of motion have low satisfaction rates with this procedure. It uses the dorsal approach. The capsule is opened, followed by complete synovectomy. Approximately 30% of the dorsal aspect of the metatarsal head is removed. Removal of >40% can lead to a painful overload of the remaining articular surface, or dorsal subluxation of the phalanx. If present, lateral osteophytes are removed as well. Remove dorsal bone until 60 to 70 degrees of dorsiflexion at the MTP joint is achieved. The average increase in dorsiflexion is approximately 25 degrees. The main benefit is the relief of dorsal impingement, which is the primary source of pain.[2][8] Cheilectomy may also be performed by a medial approach. Care is necessary to identify and protect the sensory nerve branches on the medial aspect of the toe. The medial approach allows for inspection of the metatarsal sesamoid complex, which is not accessible by a dorsal approach. Occasionally, marginal osteophytes or adhesions may be present, requiring removal. Care is necessary to repair the medial capsule at the time of closure to prevent hallux valgus.

- Moberg Procedure

- This procedure is a dorsal closing wedge osteotomy of the proximal phalanx. It can be used at the time of cheilectomy if it fails to achieve adequate dorsiflexion.[5]

- Arthrodesis

- This approach is the current standard of care for managing more severe (grade 3 to 4) hallux rigidus. Successful clinical outcomes are based on the correct positioning of the fusion. The recommended positioning of the hallux relative to the floor is between 10 degrees and 15 degrees of dorsiflexion and 10 degrees to 15 degrees of valgus.[8][9]

- Keller resection arthroplasty

- This surgery involves the removal of the base of the proximal phalanx. Indicated in low demand patients aged >70 years.[10]

- MTP arthroplasty

- Silicone implants have shown good short- term outcomes. However, long- term data shows high rates of complications.[8] Total joint implants are controversial. Generally not recommended in young or active person due to the risk of implant loosening, subsidence, plantar subluxation, and component malalignment.[8] Results have shown to be less superior compared to arthrodesis in terms of clinical outcomes, reduction in pain, complications, and revisions.[10]

- Polyvinyl alcohol hydrogel hemiarthroplasty is a new treatment option. FDA approved for implantation in July 2016 in the United States. It has similar material properties to human articular cartilage in terms of water content, tensile strength, and a compressive modulus. The implant is held in place via press-fit and sits projecting by 1.5 mm to function as both hemiarthroplasty and interpositional space. Early data shows similar outcomes to arthrodesis; however, long term data is necessary.[5]

- Cheilectomy

Differential Diagnosis

Must differentiate from other causes of first metatarsophalangeal joint pain, such as a bunion, hallux valgus, infection, turf toe, etc. Restriction in dorsiflexion, along with the presence of dorsal osteophytes, can lead to the diagnosis of hallux rigidus. Turf toe would present more acutely after traumatic injury. While hallux rigidus can have a swollen and painful great toe, laboratory evaluation can differentiate from other diseases such as septic first MTP joint or gout.

- Bunion

- Gout

- Hallux valgus

- Septic joint

- Turf toe

Prognosis

Nonoperative treatment should be the first attempted intervention, as it has shown to have good outcomes. Grady and colleagues reviewed 772 patients with either operative or nonoperative management; 55% percent of all patients had treatment success with conservative care alone.[5] As per operative treatment, first metatarsophalangeal joint arthrodesis has demonstrated an excellent outcome with a success rate as high as 85%.[10]

Complications

Cheilectomy does not prevent disease progression. Conversion rates to arthrodesis have ranged from 7% to 9% within ten years. If the procedure fails, it does not compromise further revision surgery.[2][8] A systematic review by Stevens et al. demonstrated a nonunion or delayed union rate of about 6.6% associated with arthrodesis. Also, the study showed about 20% of patients had asymptomatic nonunion that did not require treatment. Other complications may include hardware removal, joint stiffness, and metatarsalgia.[3][10] Complications associated with Keller resection arthroplasty include hallux cock-up deformity, toe-off weakness, and transfer metatarsalgia. Arthroplasty related complications include failure of arthroplasty. It has correlated with implant-related complications of 26% with the majority due to prosthetic loosening causing instability and pain during gait.[10]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients need to understand that shoe wear does not cause nor contribute to hallux rigidus. Acute and/or repetitive trauma predisposes to arthritic changes.[5]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Hallux rigidus is a common condition encountered by primary care providers. Referal to foot and ankle surgeons and podiatrists may be needed. Surgical treatment should only be an option after the failure of nonoperative treatment. Nonoperative treatments are successful for about half of all patients. Cheilectomy has demonstrated promising outcomes for the early stages of hallux rigidus. Arthrodesis of the first MTP joint remains the gold standard of treatment for advanced arthritis. Other treatments, such as PVA hydrogel implants, have good short term outcomes; however, these require additional long term studies.[3][5] Foot and nail care nurses are an integral part of the interprofessional team.

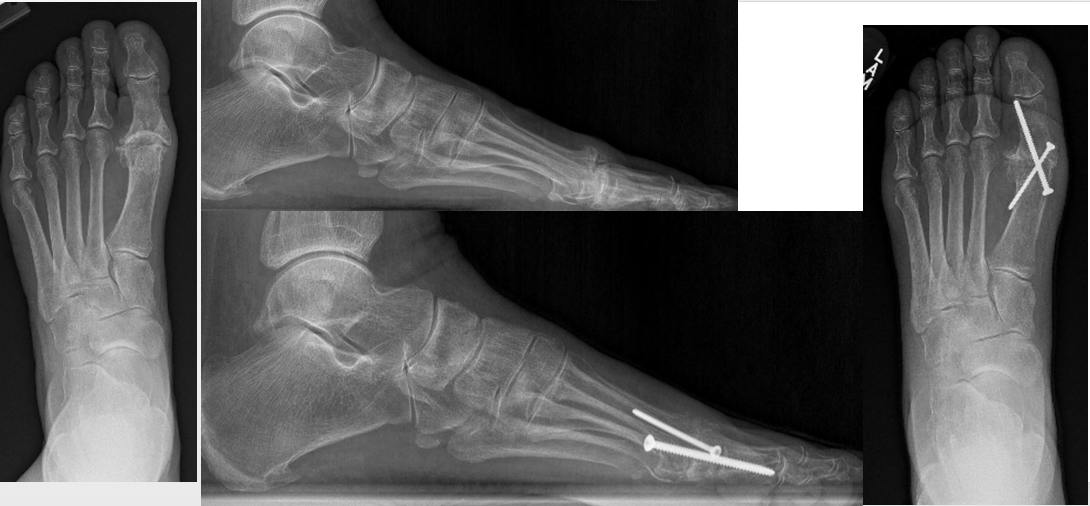

(Click Image to Enlarge)

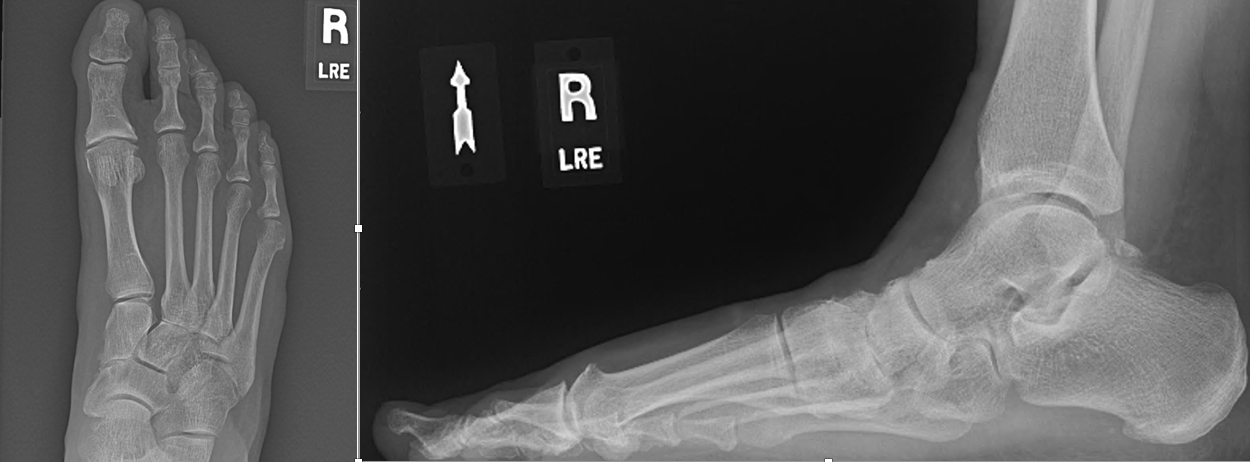

(Click Image to Enlarge)