Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Nerves

- Article Author:

- Ebubechi Okwumabua

- Article Editor:

- Johnathan Thompson

- Updated:

- 8/10/2020 5:44:50 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Nerves CME

- PubMed Link:

- Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Nerves

Introduction

The upper limb includes the scapula, clavicle, humerus, radius, ulna, carpals, metacarpals, and small bones of the hand. Innervation originates in the neck and travels down to allow muscle action of flexion, extension, pronation, supination, and rotation necessary to achieve activities of daily living.

Embryology

Nerves are of ectodermal origin. Bones, blood vessels, and muscles are of mesodermal origin. The limbs are anatomically positioned at birth through the interaction of several growth factors. Essential growth factors include sonic hedgehog (SHH), fibroblast growth factor (FGF), and the homeobox (Hox) genes. SHH is activated for appropriate growth and development of the limbs. It is activated at the zone of polarizing activity, and interacts with FGF, to ensure normal limb development.[1] FGF and Wnt-7 genes are localized at the apical ridge and contribute most to lengthening and dorsal-ventral positioning, respectively. Hox genes are responsible for segmental development in the craniocaudal direction. Mutations in the Hox genes results in limbs positioned in the wrong places.[2] One example of such an anomaly occurs when the Hox gene is mutated in the Antennapedia Drosophila fly. In this instance, the Hox mutation resulted in legs growing from the fly's head instead of antennas.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Blood supply arises from the arch of the aorta via the left subclavian and the brachiocephalic artery which provides the branch of the right subclavian artery. Both subclavian arteries become axillary arteries after passing below the first rib into the axilla. The axillary artery passes below the pectoralis minor and branches into the posterior and anterior circumflex, which go on to supply the shoulder region. The subscapular artery also arises from the axillary artery after passing below the pectoralis minor muscle and provides blood supply to the subscapular muscle and other muscles of the back and thoracic region. After the axillary nerve crosses the lower border of the teres major muscle, it becomes the brachial artery, the main blood supply to the arm. It gives rise to the deep branch of the brachial artery, which supplies the deep muscles of the arm and becomes a network of vessels around the elbow. The brachial artery travels with the median nerve into the cubital fossa where it bifurcates into the ulnar and radial arteries. These arteries provide blood supply to the remainder of the upper limb. Lesions of specific nerves which run with these arteries are of clinical and surgical significance. The following nerves and arteries are of vital importance: (1) the radial nerve, which runs with the deep branch of the brachial artery at the radial groove; (2) the axillary nerve, which runs with the posterior humeral circumflex artery and can be seen at the quadrangular space.

Nerves

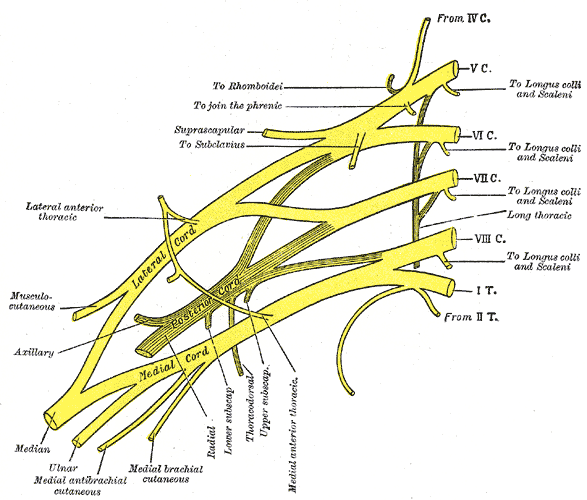

The nerves of the upper limb arise from a network called the brachial plexus, which originates in the neck from anterior divisions of the spinal nerves C5-T1.[3] The brachial plexus is divided into five sections: roots, trunks, divisions, cords, and branches. The roots travel between the anterior and middle scalene muscles in the posterior triangle of the neck. The dorsal scapular nerve comes directly and laterally off of the C5 nerve root and innervates the levator scapula, rhomboid major, and minor rhomboid muscles. The long thoracic nerve, coming from roots C5 through C7, innervates the serratus anterior muscle. The suprascapular nerve comes off the upper trunk, from roots C5-C6, and innervates the supraspinatus and infraspinatus, which are contributors to the rotator cuff apparatus. Arising from anterior divisions of C5-C6, also from the upper trunk, the subclavian nerve innervates the subclavius muscle. Continuing down the brachial plexus, one enters the region of the divisions. The divisions do not have many essential nerves directly arising from them, but immediately distal to the divisions are the cords. The cords have three sections: lateral, posterior, and medial. The lateral and medial cords communicate with each other via the lateral and medial pectoralis nerves. These nerves innervate both the pectoralis major and minor muscles. The upper and lower subscapular nerves come from the posterior cord. The lower subscapular nerve (C5-C6) innervates teres major; and both the upper and lower subscapular nerves innervate the subscapularis, the third muscle of the rotator cuff apparatus. The thoracodorsal nerve (C6-C8), which also arises from the posterior cord, innervates the levator scapulae. Coming from the medial cords are two cutaneous branches that provide tactile sensation; these are called the medial cutaneous nerve of the arm and forearm respectively.

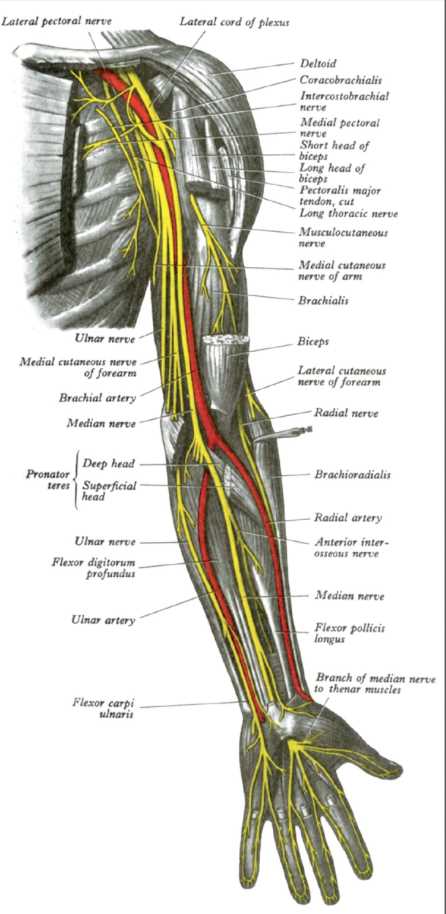

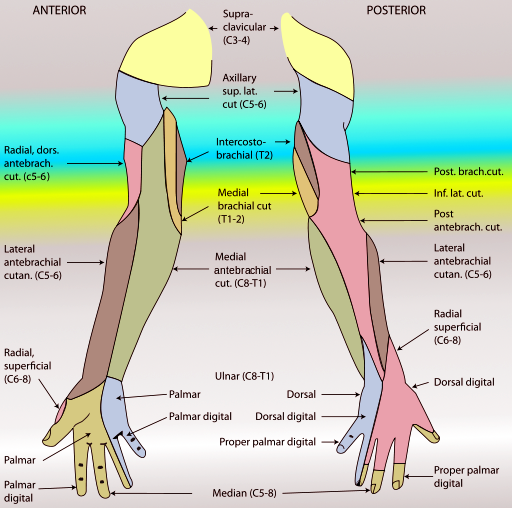

The five branches are the last segments of the brachial plexus. The terminal branches include the following nerves: musculocutaneous, axillary, radial, median, and ulnar. Each nerve has a distribution that coincides with the muscles they innervate. The musculocutaneous nerve (C5-C6) innervates the brachialis, brachioradialis, and coracobrachialis muscles. To remember these muscles, use the mnemonic "BBC." As the name states, the musculocutaneous nerve also has a cutaneous component, the cutaneous nerve of the forearm, which provides lateral sensation to the antebrachium. The axillary nerve also comes from ventral roots of C5 and C6 and innervates the deltoid and teres minor muscles.[4] The cutaneous component of the axillary nerve innervates what is known as the "regimental band," located on the upper lateral aspect of the shoulder to the lower border of the upper third of the arm. The radial nerve, a continuation of the posterior cord, innervates the extensors of the arm and forearm as well as supinators of the forearm. It also has a cutaneous component, allowing sensation to the posterior arm, forearm, and dorsal hand up to the dorsal interphalangeal joint. The median nerve, originating from nerve roots C6-T1, innervates the anterior compartment of the forearm as well as muscles in the hand.[5] The anterior compartment of the forearm is responsible for flexion of the phalanges. Specifically, the lateral aspect of the flexor digitorum profundus is innervated by the median nerve. The flexor carpi ulnaris, however, is innervated by the ulnar nerve. This is the sole exception of the anterior compartment. The lateral two lumbricals also receive innervation from the median nerve. Last but not least, the recurrent branch of the median nerve innervates the thenar muscles. The median nerve is the only nerve that passes through the carpal tunnel. Therefore, compression in this area can lead to sensory and motor deficits in the hand. The ulnar nerve, which comprises ventral nerve roots C8-T1, innervates muscles on the medial side of the forearm, medial half of flexor digitorum profundus, and the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle.[6] It also innervates the intrinsic muscles of the hand, including the medial two lumbricals and all interossei muscles. The cutaneous sensation from the medial aspect of the ring finger through the small finger also is mediated by the ulnar nerve. Compression of the ulnar nerve can occur at the Guyon canal in the medial wrist, causing sensory and motor deficits in the hand. One concept of importance is knowing where a nerve lesion occurs and what muscles will be affected. The effects of a nerve lesion will always manifest distal to the point of the injury. In the case of compression at the Guyon canal, one will see innervation deficits in the hand, but any muscle that originates in the forearm that is innervated by the ulnar nerve will still be intact. Therefore, actions such as abduction and adduction of the phalanges will be affected, but flexion of the small finger should remain intact.

Clinical Significance

As stated, the muscles distal to the lesion will be affected for all nerves described above. The example described pertained to the Guyon canal and the ulnar nerve. Another example is the compression of the median nerve. The median nerve is the only nerve that passes through the carpal tunnel, and as previously stated, will lead to sensory and motor deficits upon compression or lesion. However, we must keep in mind that the median nerve also innervates the muscles of the forearm. Before the median nerve enters the carpal tunnel, it has already innervated muscles of the forearm, including the flexor digitorum superficialis, flexor pollicis longus, pronator teres, flexor carpi radialis, the lateral component of the flexor digitorum profundus, and the pronator quadratus. Pronation of the forearm and flexion of the phalanges will be intact, except for the distal interphalangeal joints of the medial two phalanges. However, the thenar muscles will express motor deficits. Prolonged compression of the median nerve will lead to atrophy of the thenar muscles, hindering the movements of the thumb, and deficiencies in the action of the lateral two lumbricals, preventing flexion at the lateral two metacarpal joints and extension of the lateral interphalangeal joints. The sensation on the lateral aspect of the palmar surface of the hand will still be intact because the palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve arises before entry into the carpal tunnel. The palmar digital cutaneous branch travels through the carpal tunnel; this is why people with carpal tunnel sensation experience numbness and tingling in their fingers. Overall, this concept of lesions with the distal manifestation of deficits applies to all nerves. It is best to know the action of each muscle and the nerve which provides innervation. If there is a lesion, those actions will not occur in a typical fashion.[7][8]