HIV Prevention

- Article Author:

- Katie Huynh

- Article Editor:

- Peter Gulick

- Updated:

- 9/2/2020 6:54:26 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- HIV Prevention CME

- PubMed Link:

- HIV Prevention

Introduction

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in the developed world is now seen as a chronic illness due to the competency of antiretroviral therapy. Despite advancements in controlling the virus, a cure still lays out of reach. Prevention is the cornerstone of stopping the HIV epidemic. This article will briefly review the efficacy and methods of various types of HIV prevention in the United States of America.

Between 2010 and 2014, both the annual number and rate of diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States decreased. In some subgroups, the numbers and rates increased and in other decreased. The number of overall new HIV diagnoses fell 19% from 2005 to 2014. Rates of HIV in women and injection drug users continue to decline. However, for men who have sex with men (MSM) the rate of HIV diagnosis is up 6%. Black and Latino MSM is up 20%, and the subgroup of ages 13 to 24 is up an astounding 87%. The rate of HIV among white MSM is down 18%, but for those ages 13 to 24, the rate has increased by 56%.

HIV is transmitted through sexual fluids (vaginal and semen), blood, and breast milk and vertically (mother to child). In 2015, 94% of infections were attributed to sexual contact; 70% male to male (including those at dual risk with a male to male sexual contact and IVDU risk) and 24% heterosexually transmitted. [1] [2]

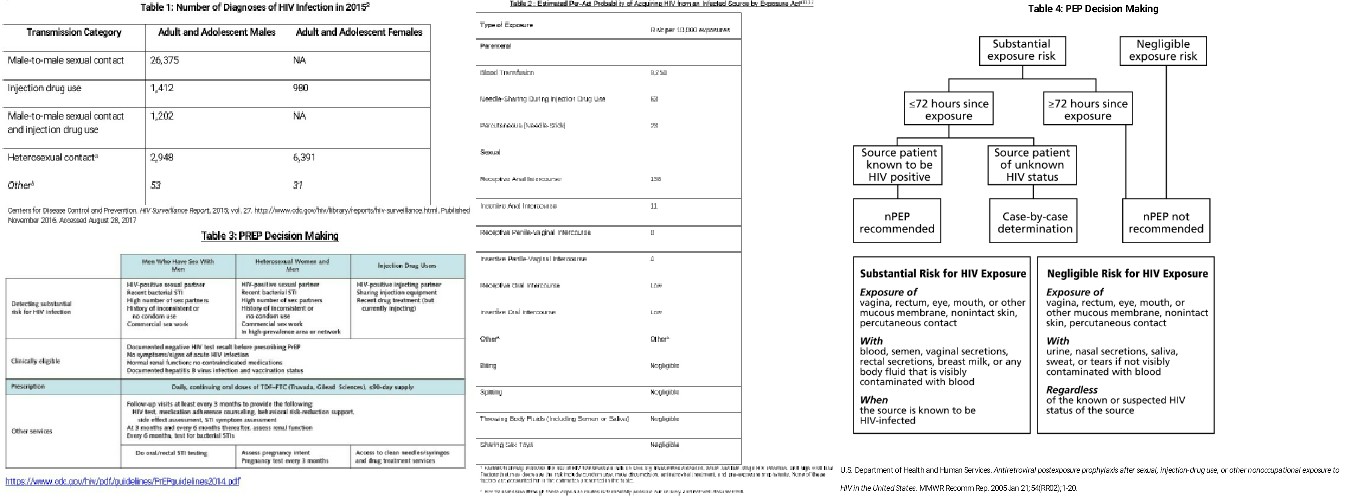

See Table 1 to compare the routes of transmission of those diagnosed with HIV in 2015.

Issues of Concern

Maternal-Fetal Transmission

Medication therapy for both mother and child during pregnancy, childbirth, and postnatally has reduced the mother to child transmission rate to less than 1%. Breast milk can transmit HIV to the child. Using the baby formula, which is readily available in the United States, eliminates that risk. In addition, rapid HIV testing at the time of delivery in high incidence areas has proven to further reduce transmission. [3]

Blood Transmission

The healthcare system has effectively instituted testing of all blood products to nearly eliminate transmission between patients through the blood. Universal precautions for health care workers have been widely accepted to decrease occupational exposure. Occupational exposures do occur, and effective post-exposure prophylaxis (oPEP) decreases the risk of infection. Effective post-exposure prophylaxis is a 28-day course of antiretrovirals that are given when the risk of HIV is considered significant within 24-72 hours of exposure. Effective post-exposure prophylaxis, occupational, and non-occupational, (nPEP) will be reviewed later in this article.

Persons who inject drugs (PWID), such as heroin, are at very high risk of being infected with HIV. Substance abuse clouds judgment and often there is needle sharing among HIV positive and HIV negative individuals. In areas where there is a high prevalence of PWID, syringe service programs (SSPs) are shown to be very effective. For example in Philadelphia, Prevention Point (a syringe exchange program) has played a huge role in reducing the rate of those who acquired HIV from injecting drugs from 42% in 2005 to 5% in 2015. In November 2016, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued a report stating that syringe programs can greatly decrease the risk of acquiring HIV in people injecting drugs. One study in 2015, showed that injection drug users who received all of their needles from a syringe exchange program shared needles 13% of the time. In contrast, those that didn’t receive all of their needles from a syringe exchange program shared needles 41% of the time.[4]

People who inject drugs are also at high risk of being undiagnosed, and therefore, they possibly transmit the virus through both blood and sexual encounters. In addition to access to clean needles, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) may be an ideal prevention method for many injection drug users. PrEP is one pill, containing two antiretrovirals, that is taken daily in those considered at risk of acquiring HIV. PrEP has shown to be very effective in reducing the risk of HIV infection and will be explored in detail later in this article. Syringe service programs also link PWID to PrEP, harm reduction teaching, access to condoms and connection to HIV and HCV testing and treatment.[5]

Sexual Transmission

Sexual transmissions still account for the bulk of new infections in the United States. Many factors affect the risk of transmission: type of sexual encounter, viral load of HIV positive partner and use/type of protective measures such as a barrier method or PREP. See Table 2 at the end of this article for a more detailed comparison of risks.

Available barrier methods include male and female condoms and dental dams. Male condoms continue to be the mainstay of HIV prevention as the most effective, and available method. Male condoms are cheap, readily available and also protect against many other sexually transmitted diseases. Unfortunately, the use of male condoms is primarily the decision of the insertive male partner. The receiving partner may not have control to protect them. Condoms also are only effective when consistently used at every sexual encounter. One meta-analysis (looking at male-male, male-female, and unstated sexual risk factors) estimated condoms to be 80% to 85% effective at reducing HIV transmission.

Another metanalysis showed condoms reduce HIV transmission by more than 70% when used consistently by HIV serodiscordant heterosexual couples. [6]

Female condoms have the advantage of transferring decision making to the female, yet they have lacked widespread acceptance and understanding of the method. Dental dams are a thin sheet of latex that can be used during cunnilingus or anilingus. Risks of oral sex practices are still underestimated by many, and dental dams are not commonly integrated into regular use at this time.

PREP

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) has been the newest addition to HIV prevention. Prep has shown to be highly-effective, FDA-approved and recommended by the CDC.

On May 14, 2014, the US Public Health Service released the first comprehensive clinical practice guidelines for PrEP (www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/guidelines/PrEPguidelines2014.pdf). Several large trials evaluated PrEP among gay and bisexual men, heterosexual men and women, and injection drug users. Those participating in the trials received pills containing either PrEP or placebo, along with intensive counseling on safe-sex behavior including access to condoms and regular testing for sexually transmitted diseases including HIV. In all of these studies, the risk of getting HIV infection was lower (up to 92% lower) for participants who took the medicines consistently than for those who did not take the medicines.

PrEP is one tablet, Truvada (tenofovir/emtricitabine), that is a combination of two antiretrovirals taken every day by those at high risk for acquiring HIV. The provider is responsible for evaluating patients at high risk, screen for HIV, HBV and renal disease before starting PREP. Truvada is only part of an HIV treatment regimen and when prescribed to someone with HIV can cause resistance and suboptimal viral control. Therefore, HIV testing is required every three months. Truvada is also used to treat HBV and the presence of HBV would not exclude using PREP but would need to be evaluated separately for use. The tenofovir component of Truvada can rarely cause renal disease, so a baseline renal function test is essential. PrEP does not prevent STIs or pregnancy. Another disadvantage is that the efficacy is greatly reduced with a lack of compliance with daily dosing. PrEP is expensive (although usually free once applying to pharmaceutical program), requires engagement at a health center and frequent follow-up visits.

Table 3 summarizes PrEP decision making.

PrEP holds the power to revolutionize HIV prevention. It allows equal decision making among sexual partners and takes away the pressure of barrier methods during sex. It also protects those who share needles. Uptake of prescribing PrEP is still not common among medical providers across LL specialties. Trials are currently underway for injectable PrEP medications that could be given every 2 to 3 months. The coming years will show if it is possible to make available to all populations, especially those most at risk.[5]

PEP

Post-exposure prophylaxis is also gaining ground as a commonly used method to prevent HIV. The decision to begin PEP is based on calculating the risk of taking PEP against the risk of acquisition of HIV during exposure. Risk of HIV transmission is the risk that the source is HIV-positive (including a viral load of source patient) and the risk of the type of exposure.

Non-occupational PEP (nPEP) is given when an individual has been exposed to a confirmed or suspicious HIV positive body secretion of semen, vaginal fluid, or blood and seeks medical treatment within 72 hours. If the source patient is known to be HIV negative or the exposure is more than 72 hours in the past nPEP is not recommended. If the source is known to be positive, the type of exposure needs is evaluated for the significance of the risk. (See Table 3 below). If the HIV status of the source patient is unknown, evaluation is on a case by case basis. A rapid HIV test should be obtained as well as evaluation for any other exposure-related risks (sexually transmitted diseases, hepatitis A and B, and pregnancy).

Occupational PEP (oPEP) was used as a model to create nPEP, and in many ways, they are similar. Antiretroviral therapy needs to be started as soon as possible, preferably less than 72 hours and continued for 4 weeks. The preferred regimen for both nPEP and oPEP for otherwise healthy adults and adolescents is tenofovir 300 mg/emtricitabine 200 mg once daily with either raltegravir 400mg twice daily or dolutegravir 50 mg once daily for 4 weeks.

In oPEP, the type of exposure may be a more unique, mucous membrane, or different body fluids. There is also usually more ability to test the source patient in occupational exposure. The main difference between non-occupational and occupational PEP is the protocol for nPEP implements risk reduction into medical visits. Patients seeking nPEP should be referred to PrEP if at repeated risk for HIV infection, or if nPEP has been sought more than once in the past 12 months.

Post-exposure prophylaxis regimens have low side effects, minimal risk of HIV resistance yet use among healthcare providers is still lacking. Providers should take full advantage of the PEP consultation service for clinicians which is a live hotline from 9 am to 2 am ET. They can be reached at 1-888-448-4911. See Table 4 for PEP decision making.[7]

TasP

Treatment as Prevention (TasP) is a campaign that engages patients and providers to treat HIV, not only for the patient's health but to reduce the risk of transmission to others. Popularly known as "U=U". It has been shown that if a patient maintains an undetectable viral load, that HIV will be untransmittable. The PARTNER 1 study looked at condomless sexual intercourse in 1166 HIV-discordant couples in which the partner with HIV was receiving ART and achieved viral suppression (HIV-1 RNA viral load <200 copies/mL). 58,000 condomless sexual acts were observed and there were no HIV transmissions as a result of these sexual acts. This study in addition to others launched the assurance that providers and patients can use the goal of maintaining viral suppression as an important part of HIV prevention.[8]

Clinical Significance

HIV infections are still occurring daily in every type of population in the United States. To end this epidemic, every healthcare provider in every specialty should be prepared to offer relevant HIV prevention methods to their patients. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is the newest addition to the established primary HIV prevention tools such as condom use, reducing community viral load through antiretroviral therapy, and syringe exchange programs. Post-exposure prophylaxis and prenatal surveillance are other established methods.

PrEP uptake among healthcare providers is an important focus of the HIV prevention campaign. The CDC recommends screening all patients for PrEP use, especially young MSM, sexually active heterosexuals and those that inject drugs. HIV prevention should be an integrated component of every healthcare practice. Despite better treatment options, HIV remains a serious disease that deserves the attention of the healthcare community and an effort to prevent every infection possible.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The burden of HIV prevention lies not only among direct care medical staff (including medical assistants, registered nurses, and providers,) but also in the community. One review of PREP uptake among MSM showed that socioeconomic factors and government policies are affecting the use of PREP to prevent HIV in this population.[9] Among PWID, the perceived risk seems to influence PREP uptake as well as lower rates among youth and women who inject drugs. [10][11][10] These findings remind us that engagement beyond the medical setting is essential for HIV prevention. Partnering with community organizations will also improve linkage to care for HIV treatment once diagnosed. Decreasing the time to viral suppression will further reduce the risk of HIV transmission. [12]