Intracranial Hemorrhage

- Article Author:

- Steven Tenny

- Article Editor:

- William Thorell

- Updated:

- 6/30/2020 6:23:04 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Intracranial Hemorrhage CME

- PubMed Link:

- Intracranial Hemorrhage

Introduction

Intracranial hemorrhage encompasses four broad types of hemorrhage: epidural hemorrhage, subdural hemorrhage, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and intraparenchymal hemorrhage.[1][2][3] Each type of hemorrhage is different concerning etiology, findings, prognosis, and outcome. This article provides a broad overview of the types of intracranial hemorrhage.

Etiology

Epidural Hematoma

An epidural hematoma can either be arterial or venous in origin. The classical arterial epidural hematoma occurs after blunt trauma to the head, typically the temporal region. They may also occur after a penetrating head injury. There is typically a skull fracture with damage to the middle meningeal artery causing arterial bleeding into the potential epidural space. Although the middle meningeal artery is the classically described artery, any meningeal artery can lead to arterial epidural hematoma.[4]

A venous epidural hematoma occurs when there is a skull fracture, and the venous bleeding from the skull fracture fills the epidural space. Venous epidural hematomas are common in pediatric patients.

Subdural Hematoma

Subdural hemorrhage occurs when blood enters the subdural space which is anatomically the arachnoid space. Commonly subdural hemorrhage occurs after a vessel traversing between the brain and skull is stretched, broken, or torn and begins to bleed into the subdural space. These most commonly occur after a blunt head injury but may also occur after penetrating head injuries or spontaneously.[5][6]

Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

A subarachnoid hemorrhage is bleeding into the subarachnoid. Subarachnoid hemorrhage is divided into traumatic versus non-traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage. A second categorization scheme divides subarachnoid hemorrhage into an aneurysmal and non-aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage occurs after the rupture of a cerebral aneurysm allowing for bleeding into the subarachnoid space. Non-aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage is bleeding into the subarachnoid space without identifiable aneurysms. Non-aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage most commonly occurs after trauma with a blunt head injury with or without penetrating trauma or sudden acceleration changes to the head.[7]

Intraparenchymal Hemorrhage

Intraparenchymal hemorrhage is bleeding into the brain parenchyma proper. There is a wide variety of reasons due to which hemorrhage can occur including, but not limited to, hypertension, arteriovenous malformation, amyloid angiopathy, aneurysm rupture, tumor, coagulopathy, infection, vasculitis, and trauma.

Epidemiology

Epidural Hematoma

Epidural hematomas are present in approximately 2% of head injury patients and account for 5% to 15% of fatal head injuries. Approximately 85% to 95% of epidural hematomas have an overlying skull fracture.

Subdural Hematoma

The incidence of subdural hematoma is estimated to be between 5% to 25% of patients with a significant head injury. There is an annual incidence of one to five cases per 100,000 population per year with a male to female ratio of 2:1. The incidence of subdural hematomas increases throughout life.

Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

Subarachnoid hemorrhage accounts for approximately 5% of all strokes and has an incidence of approximately two to 25 per 100,000 person-years for those over the age of 35. The incidence trends up slowly as patients age and may be very slightly more frequent in females than males (1.15:1 for the female to male ratio).

Intraparenchymal Hemorrhage

Intraparenchymal hemorrhage accounts for 10% to 20% of all strokes. Intraparenchymal hemorrhage incidence increases for those aged 55 and older with an increasing incidence as age increases. There is some controversy regarding gender differences, but there may be a slight male predominance.

Pathophysiology

Epidural Hematoma

Epidural hematomas occur when blood dissects into the potential space between the dura and inner table of the skull. Most commonly this occurs after a skull fracture (85% to 95% of cases). There can be damage to an arterial or venous vessel which allows blood to dissect into the potential epidural space resulting in the epidural hematoma. The most common vessel damaged it the middle meningeal artery underlying the temporoparietal region of the skull.

Subdural Hematoma

Subdural hematoma has multiple causes including head trauma, coagulopathy, vascular abnormality rupture, and spontaneous. Most commonly head trauma causes motion of the brain relative to the skull which can stretch and break blood vessels traversing from the brain to the skull. If the blood vessels are damaged, they bleed into the subdural space.

Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

Subarachnoid hemorrhage most commonly occurs after trauma where cortical surface vessels are injured and bleed into the subarachnoid space. Non-traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage is most commonly due to the rupture of a cerebral aneurysm. When aneurysm ruptures, blood can flow into the subarachnoid space. Other causes of subarachnoid hemorrhage include arteriovenous malformations (AVM), use of blood thinners, trauma, or idiopathic causes.

Intraparenchymal Hemorrhage

Non-traumatic intraparenchymal hemorrhage most often occurs secondary to hypertensive damage to cerebral blood vessels which eventually burst and bleed into the brain. Other causes include rupture of an arteriovenous malformation, rupture of an aneurysm, arteriopathy, tumor, infection, or venous outflow obstruction. Penetrating and non-penetrating trauma may also cause intraparenchymal hemorrhage.

History and Physical

Epidural Hematoma

Patients with epidural hematoma report a history of a focal head injury such as blunt trauma from a hammer or baseball bat, fall, or motor vehicle collision. The classic presentation of an epidural hematoma is a loss of consciousness after the injury, followed by a lucid interval then neurologic deterioration. This classic presentation only occurs in less than 20% of patients. Other symptoms that are common include severe headache, nausea, vomiting, lethargy, and seizure.

Subdural Hematoma

A history of either major or minor head injury can often be found in cases of subdural hematoma. In older patients, a subdural hematoma can occur after trivial head injuries including bumping of the head on a cabinet or running into a door or wall. An acute subdural can present with recent trauma, headache, nausea, vomiting, altered mental status, seizure, and/or lethargy. A chronic subdural hematoma can present with a headache, nausea, vomiting, confusion, decreased consciousness, lethargy, motor deficits, aphasia, seizure, or personality changes. A physical exam may demonstrate a focal motor deficit, neurologic deficits, lethargy, or altered consciousness.

Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

A thunderclap headache (sudden severe headache or worst headache of life) is the classic presentation of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Other symptoms include dizziness, nausea, vomiting, diplopia, seizures, loss of consciousness, or nuchal rigidity. Physical exam findings may include focal neurologic deficits, cranial nerve palsies, nuchal rigidity, or decreased or altered consciousness.

Intraparenchymal Hemorrhage

Non-traumatic intraparenchymal hemorrhages typically present with a history of sudden onset of stroke symptoms including a headache, nausea, vomiting, focal neurologic deficits, lethargy, weakness, slurred speech, syncope, vertigo, or changes in sensation.

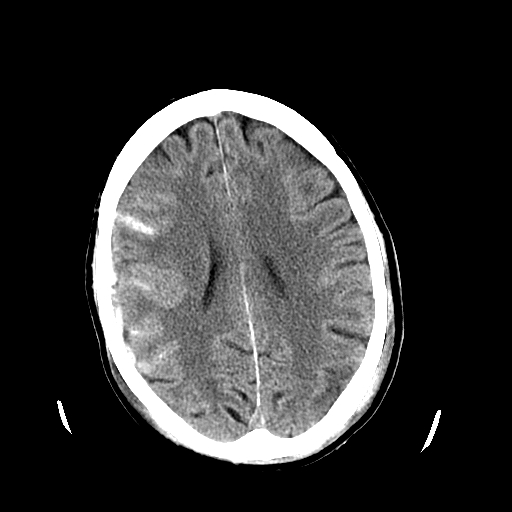

Evaluation

Initial evaluation includes airway, breathing, and circulation as patients can rapidly deteriorate and require intubation. A detailed neurologic examination helps identify neurologic deficits. With increasing intracranial pressure there may be a Cushing response (hypertension, bradycardia, and bradypnea). Emergent CT head without contrast is the imaging choice of the test due to its high sensitivity and specificity for identifying significant epidural hematomas. Historically cerebral angiography could identify the shift in cerebral blood vessels, but cerebral angiography has been supplanted by CT imaging.

Laboratory studies should also be considered including a complete blood count to check for thrombocytopenia, coagulation studies (PTT, PT/INR) to check for coagulopathy and basic metabolic panel to check for electrolyte abnormalities.

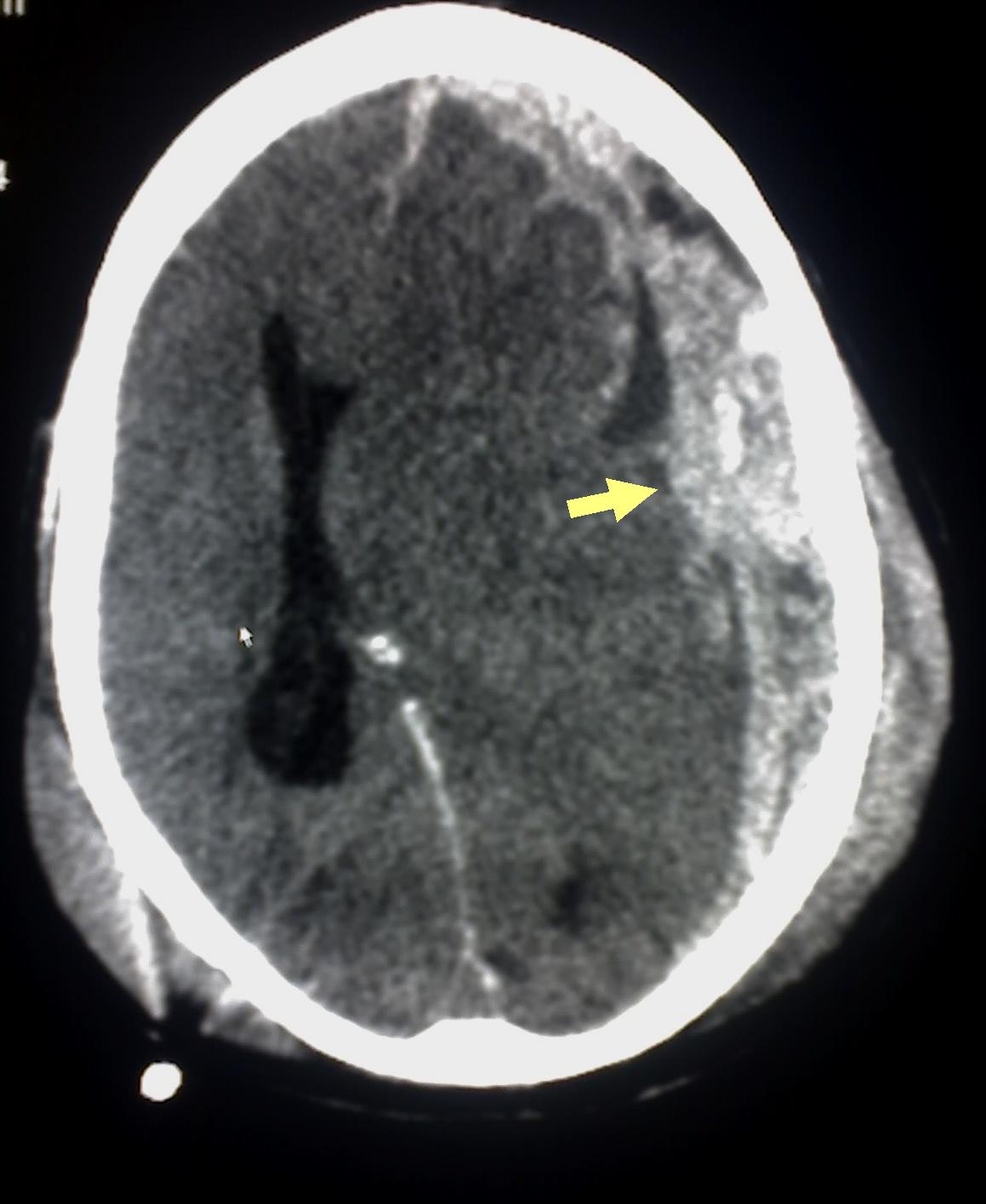

Subdural Hematoma

After ensuring the medical stability of the patient, a detailed neurologic exam can help identify any specific neurologic deficits. Most commonly a computed tomography (CT) scan of the head without contrast is the first imaging test of choice. An acute subdural hematoma is typically hyperdense with chronic subdural being hypodense. A subacute subdural may be isodense to the brain and more difficult to identify.

Laboratory studies should also be considered including a complete blood count to check for thrombocytopenia, coagulation studies (PTT, PT/INR) to check for coagulopathy and basic metabolic panel to check for electrolyte abnormalities.

Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

Initial evaluation includes assessing and stabilizing the airway, breathing, and circulation (ABCs). Patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage can rapidly deteriorate and may need emergent intubation. A thorough neurologic examination can help identify any neurologic deficits.

The initial imaging for patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage is computed tomography (CT) head without contrast. If the patient is given contrast, this can obscure the subarachnoid hemorrhage. Acute subarachnoid hemorrhage is typically hyperdense on CT imaging. If the CT head is negative and there is still strong suspicion for subarachnoid hemorrhage a lumbar puncture should be considered. The results of the lumbar puncture may show xanthochromia. A lumbar puncture performed before 6 hours of the subarachnoid hemorrhage may fail to show xanthochromia. Additionally, lumbar puncture results may be confounded if a traumatic tap is encountered.

Identifying the cause of non-traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage will help guide further treatment. Common workup includes either a CT angiogram (CTA) of the head and neck, magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) of the head and neck, or diagnostic cerebral angiogram of the head and neck done emergently to look for an aneurysm, AVM or another source of subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Laboratory studies should also be considered including a complete blood count to check for thrombocytopenia, coagulation studies (PTT, PT/INR) to check for coagulopathy and basic metabolic panel to check for electrolyte abnormalities.

Intraparenchymal Hemorrhage

Once the medical stability of the patient is ensured, CT head without contrast is the first diagnostic test most commonly performed. The imaging should be able to identify acute intraparenchymal hemorrhage as hyperdense within the parenchyma. Depending on the history, physical and imaging findings and patient an MRI brain with and without contrast should be considered as tumors within the brain may present as intraparenchymal hemorrhage. Other imaging to consider include CTA, MRA or diagnostic cerebral angiogram to look for cerebrovascular causes of the intraparenchymal hemorrhage. Evaluation should also include a complete neurologic exam to identify any neurologic deficits.

Laboratory studies should also be considered including a complete blood count to check for thrombocytopenia, coagulation studies (PTT, PT/INR) to check for coagulopathy and basic metabolic panel to check for electrolyte abnormalities.

Treatment / Management

Treatment begins with advanced trauma life support (ATLS) including airway control, ensuring adequate ventilation and circulation. Intravenous (IV) access should be secured. If the patient has a Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) of 8 or less or worsening neurologic status, intubation should be performed. Immediate neurosurgical consultation should be obtained for patients with epidural hematomas as they may expand over time due to continued bleeding. Definitive treatment is an evacuation of the hematoma and stopping the bleeding source. Some smaller epidural hematomas may be managed non-surgically and watched closely for resolution.

Subdural Hematoma

Treatment begins with ensuring adequate airway, breathing, and circulation. Intubation should be considered if the patient has a deteriorating GCS or GCS of 8 or less. Immediate neurosurgical consultation should be obtained as emergency surgery may be required to evacuate the subdural hematoma. The definitive treatment for subdural hematomas is an evacuation, but depending on the size and location some subdural hematomas may be watched for resolution.

Non-surgical management options include repeat imaging to ensure subdural stability, the reversal of anticoagulation, platelet transfusions for thrombocytopenia or dysfunctional platelets, observation with frequent neurologic assessments for deterioration, and/or controlling hypertension. There is controversy about whether steroids can help stabilize the size of the subdural hematoma while giving it time to resorb or until surgical treatment.

Surgical management options include a twist drill hole, burr hole(s), and craniotomy for evacuation. Data suggests that a twist drill hole has the lowest surgical complication rate with the highest recurrence rate. A craniotomy has the highest surgical complication rate with the lowest recurrence rate of the surgical options, and burr hole(s) evacuation falls somewhere between a twist drill hole and a craniotomy for complication rate and recurrence rate.

Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

Subarachnoid hemorrhage may depend if it is a traumatic or non-traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage. For traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage, the ABCs of medicine must occur first. Early consultation with neurosurgery should be considered. If the patient is on anticoagulation or antiplatelet agents consideration should be given to reversing their effects. Care is typically conservative with close assessments of vitals and neurologic status. In obtunded patients, there may be a need for intracranial pressure (ICP) monitor and/or external ventricular drain (EVD). Patients should be monitored for hydrocephalus or cerebral swelling. Repeat imaging can verify the improvement of the traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage. Sometimes aneurysmal rupture or incompetence of other intracranial vascular malformations can masquerade as traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage. If there is no clear and convincing history of a traumatic origin, then a non-traumatic etiology for the subarachnoid hemorrhage should be sought.

In non-traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage, the etiology of the hemorrhage must be ascertained and addressed. Early consultation with neurosurgery should be considered. Treatment varies depending on the etiology of the hemorrhage but can include treatment of an aneurysm or arteriovenous malformation or other etiology. Additionally, there should be a low threshold for placement of an external ventricular drain (EVD) due to the risk of hydrocephalus.

Intraparenchymal Hemorrhage

Intraparenchymal hemorrhage can be life-threatening and treatment starts with the ABCs of medicine and stabilization of the patient. Blood pressure should be controlled to decrease the risk of further hemorrhage. Early consultation with neurosurgery should be considered. The treatment of intraparenchymal hemorrhage depends on the etiology of the hemorrhage. Treatment options are variable and include aggressive surgical evacuation, craniectomy, catheter-based dissolution or observation. Surgical evacuation is controversial for some forms of intraparenchymal hemorrhage. Although many intraparenchymal hemorrhages are secondary to cerebrovascular disease and hypertension, the surgeon should anticipate encountering other underlying pathology including an aneurysm, AVM, and/or tumor when evacuating an intraparenchymal hemorrhage. Sometimes evacuation of the hematoma may be more detrimental than the hematoma itself, and a craniectomy is performed instead to allow for cerebral swelling. There are a number of catheter-based systems which try to dissolve the hemorrhage. A discussion of these is beyond the scope of this article. Smaller and non-operable hemorrhages may be managed medically with control of blood pressure, the reversal of anticoagulation or antiplatelet agents, and neuroprotective strategies to prevent and/or mitigate secondary cerebral injury.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses of intracranial hemorrhage include:

- Infection - Subdural empyema may mimic a subdural hemorrhage

- Recent contrast administration

- Subdural hygroma - May appear similar to chronic subdural hemorrhage

- Tumors - meningioma may mimic an extradural hemorrhage

Prognosis

The prognosis depends on several factors including:

- Age of the patient

- Comorbidities

- Consumption of antiplatelets or anticoagulants

- Glasgow Coma Scale score at presentation

- The size of pupils at presentation

- Location of the bleed

- Presence of other injuries

- Time delay for surgical intervention, if needed.

Complications

The main complications include:

- Neurological deficits

- Brain herniation

- Infarcts

- Rebleed

- Vasospasm

- Seizures

- Death

Deterrence and Patient Education

The patients, once they recover, should be educated on the importance of rehabiltation treatment and drug intake as prescribed. They cannot drive unless told so.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Patients who present with CNS bleeding are best managed by an interprofessional team that includes a neurologist, neurosurgeon, radiologist, intensivist, neurosurgery nurses, physical therapist, pulmonologist, and other allied health specialists like speech, occupational and physical therapists. Many of these patients need admission to the ICU and the care depends on the degree of physical and other neurological deficits. The outcomes depend on the type and extent of bleed, age, other comorbidities, and severity of neurological deficit at the time of admission.[14][7][15]

(Click Image to Enlarge)