Iron Deficiency Anemia

- Article Author:

- Matthew Warner

- Article Editor:

- Muhammad Kamran

- Updated:

- 8/10/2020 4:43:28 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Iron Deficiency Anemia CME

- PubMed Link:

- Iron Deficiency Anemia

Introduction

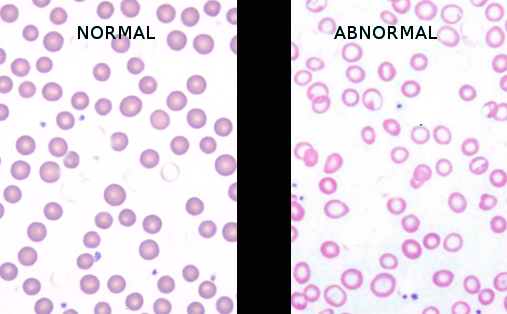

Anemia is defined as hemoglobin below two standard deviations of the mean for the age and gender of the patient. Iron is an essential component of the hemoglobin molecule. The most common cause of anemia worldwide is iron deficiency, which results in microcytic and hypochromic red cells on the peripheral smear. Several causes of iron deficiency vary based on age, gender, and socioeconomic status. The patient often will have nonspecific complaints such as fatigue and dyspnea on exertion. Treatment is a reversal of the underlying condition as well as iron supplementation. Iron supplementation is most often oral, but certain cases may require intravenous iron. Patients with iron-deficient anemia have been found to have a longer hospital stay, along with a higher number of adverse events.[1][2][3]

Etiology

The cause of iron-deficiency anemia varies based on age, gender, and socioeconomic status. Iron deficiency may result from insufficient iron intake, decreased absorption, or blood loss. Iron-deficiency anemia is most often from blood loss, especially in older patients. It may also be seen with low dietary intake, increased systemic requirements for iron such as in pregnancy, and decreased iron absorption such as in celiac disease. In neonates, breastfeeding is protective against iron deficiency due to the higher bioavailability of iron in breast milk compared to cow's milk; iron deficiency anemia is the most common form of anemia in young children on cow's milk. In developing countries, a parasitic infestation is also a significant cause of iron-deficiency anemia. Dietary sources of iron are green vegetables, red meat, and iron-fortified milk formulas.[4][5][6]

Epidemiology

Approximately 25% of people worldwide have anemia. Iron deficiency, the most common cause, is responsible for 50% of all anemias. The rate of iron deficiency is higher in developing countries compared to the United States, where the prevalence of iron-deficiency anemia in men under 50 is 1%. In women of childbearing age in the United States, the rate is 10% due to losses from menstruation, while 9% of children ages 12 to 36 months are iron-deficient, and one-third of these children develop anemia. While the rate of iron-deficiency anemia is low in the United States, low-income families are particularly at risk.[7][1]

Pathophysiology

Iron is essential for the production of hemoglobin. The depletion of iron stores may result from blood loss, decreased intake, impaired absorption, or increased demand. Iron-deficiency anemia could arise from occult gastrointestinal bleeding. Adults older than 50 years of age with iron-deficiency anemia and gastrointestinal bleeding need to be evaluated for malignancy. However, gastrointestinal diagnostic evaluation fails to establish a cause in one-third of patients assessed. Iron deficiency will lead to microcytic hypochromic anemia on the peripheral blood smear. Because iron is the most common single-nutrient deficiency, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends supplementation. When to begin supplementation and the needed dosage depends on the age and diet of the child.

Histopathology

The examination of a bone marrow sample stained for iron, such as Prussian blue stain, will reveal reduced amounts of iron in macrophages.

History and Physical

Most patients are asymptomatic and identified through a blood test. Pallor is the most important clinical sign, but it is not usually visible unless hemoglobin falls to 7 g/dL to 8 g/dL. A thorough history may reveal fatigue, a decreased ability to work, shortness of breath, or worsening congestive heart failure. Children may have cognitive impairment and developmental delays. Patients should be questioned regarding their diet as well as asked about any bleeding from menorrhagia or gastrointestinal sources. The physical exam may reveal pale skin and conjunctiva, resting tachycardia, congestive heart failure, and guaiac-positive stool.

Evaluation

Laboratory evaluation will identify anemia. The hemoglobin indices in iron deficiency will demonstrate a low mean corpuscular hemoglobin and mean corpuscular hemoglobin volume. Hematoscopy shows microcytosis, hypochromia, and anisocytosis, as reflected by a red cell distribution width higher than the reference range. Serum levels of ferritin, iron, and transferrin saturation will be decreased. Serum ferritin is a measure of the total body iron stores. The total iron-binding capacity will be increased. Stool for occult blood may reveal a gastrointestinal source of bleeding. A simple mean corpuscular hemoglobin/RBC index, or Mentzer index, can help differentiate between the two causes of microcytic/hypochromic anemia. These causes are iron deficiency and thalassemia minor. An index greater than 15 suggests iron deficiency, while an index less than 11 suggests thalassemia minor. The definitive test to rule out thalassemia minor is hemoglobin electrophoresis. Other tests like an iron profile are necessary for severe anemia or when anemia does not respond to iron therapy. Low ferritin is a reliable marker of iron deficiency. However, a ferritin level that is within the reference range or elevated is not very useful in patients with inflammatory conditions such as malignancies, infection, and collagen disease. This is because it is an acute-phase reactant. The standard for establishing iron deficiency is a bone marrow aspiration or biopsy followed by iron staining since it is unaffected by inflammation. However, the cost and invasiveness of this test make it less feasible; it is rarely performed for this reason.[8]

Treatment / Management

The treatment of iron-deficiency anemia includes treating the underlying cause, such as gastrointestinal bleeding and oral iron supplementation. Iron supplementation should be taken without food to increase absorption. Low gastric pH facilitates iron absorption. Rapid response to treatment is often seen in 14 days. It is manifested by the rise in hemoglobin levels. Iron supplementation is needed for at least three months to replenish tissue iron stores and should proceed for at least a month even after hemoglobin has returned to normal levels. Ferrous sulfate is an inexpensive and effective therapy, usually given in two to three divided doses daily. The adverse effects of oral iron include constipation, nausea, decreased appetite, and diarrhea. Intravenous iron may be required if the patient is intolerant to oral iron, has malabsorption such as celiac disease, post-gastrectomy, or achlorhydria, or the losses are too high for oral therapy. Although intravenous iron is more reliably and quickly distributed to the reticuloendothelial system than oral iron, it does not provide for a more rapid increase in hemoglobin levels.

The most common adverse effect of intravenous iron is nausea. While rare, anaphylaxis may occur with intravenous iron infusions. Extravasation of iron solutions into the subcutaneous tissue causes brownish stains that can be permanent and aesthetically unpleasant for the patient. Dietary counseling is usually necessary for management. Teenage girls who are experiencing excessive menstrual blood loss may benefit from iron and hormonal therapy.[3][9][10]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of iron deficiency anemia include:

- Lead poisoning

- Microcytic anemia

- Anemia of chronic disease

- Hemoglobin CC disease

- Hemoglobin DD disease

- Autoimmune hemolytic anemia

- Hemoglobin S-beta thalassemia

Prognosis

The short-term prognosis for most patients is excellent. However, if the underlying cause is not corrected, the prognosis is poor.

Chronic iron deficiency can lead to death from an underlying lung or heart disorder.

Complications

The complications of iron deficiency anemia include:

- Increased risk of infections

- Heart conditions

- Developmental delay in children

- Pregnancy complications

- Depression

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Those with severe iron deficiency anemia should limit physical activity until the anemia has been corrected.

March hemoglobinuria can also lead to iron deficiency anemia and may require some modification in either shoe wear or physical activity.

Consultations

The following should be consulted in iron deficiency anemia:

- Surgeon if there is a surgical gastrointestinal cause

- Gastroenterologist for endoscopy and localization of the gastrointestinal tract bleeding

- Radiologist if the bleeding is brisk and can be managed by embolization

Deterrence and Patient Education

Populations at high risk should be considered for prophylaxis with iron therapy. These groups include women with heavy menstrual cycles, frequent blood donors, adolescent girls, and people who eat strict vegetarian diets. Empirical iron supplements for everyone are not recommended as there is no evidence that this is beneficial but may be harmful.

Pearls and Other Issues

Patients often have nonspecific symptoms with anemia, and a careful history and physical examination are needed. In the pediatric population, routine screening starting at 9 to 12 months and annually after that has helped prevent the development of severe anemia. In the adult population, evaluating the gastrointestinal system as a potential cause of iron-deficient anemia can be a diagnostic challenge. The emerging role of less invasive testing for celiac disease, autoimmune atrophic gastritis, and Heliobacter pylori infections has improved disease recognition and diagnosis. While there is always the potential for relapse after iron supplementation, there is a lack of guidance regarding when to stop iron supplementation. An additional pitfall of iron deficiency anemia is worse outcomes with many medical conditions. Some of the adverse effects of patients with iron-deficient anemia are higher mortality, more extended hospital stays, and more cardiovascular events.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Although iron deficiency is one of the oldest and most common medical disorders, the condition still has not received adequate clinical attention and evaluation. Many children, elderly patients, and pregnant women continue to have undiagnosed iron deficiency anemia or remain under-treated. Evidence from an interprofessional panel of clinicians reveals that iron-deficiency anemia has a high prevalence in hospitalized patients. It is associated with worse outcomes, including more extended hospital stays and poor quality of life. There are also risks for those who receive blood transfusions. The panel has recommended several strategies in early diagnosis, treatment, and follow up of these patients.[11] The most critical recommendation is a prompt referral to a specialist; not all causes of iron deficiency anemia are merely due to a gastrointestinal bleed or heavy menstrual cycles. The primary care health care provider plays a vital role as he or she is almost always the first to note the presence of iron deficiency anemia. Others who are essential in detecting iron-deficiency anemia include the following:

- Laboratory technologists determine serum ferritin, transferrin, vitamin levels, and function of the real system.

- Hematologists determine the cause.

- Pharmacists determine the best formula for iron and the presence of adverse effects. Replacement therapy is either with intravenous or oral formulas of iron, with red cell transfusions reserved for emergency situations. Each has its benefits and limitations.

- Nurses ensure compliance with treatment and educate patients on symptoms and signs of the anemia.

- Internists follow and monitor patients.

Guidelines

The United States Preventive Services Task Force has concluded that the evidence is not sufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for iron deficiency anemia in pregnant women and children ages 6 to 24 months.[12][Level V]

Outcomes

Most studies on iron replacement therapies were done several decades ago. Many of these studies were not randomized, and the follow-up appointments were short. Reports of treatment of iron deficiency anemia are all based on expert opinion, but there is a clear benefit of treatment during the short term.[13][Level V] There remain significant gaps in how long the treatment should be done, as well as ethnic differences in response to iron and who is at risk for developing adverse reactions.

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)