Kayser-Fleischer Ring

- Article Author:

- Nivedita Pandey

- Article Editor:

- Savio John

- Updated:

- 8/11/2020 11:35:01 AM

- For CME on this topic:

- Kayser-Fleischer Ring CME

- PubMed Link:

- Kayser-Fleischer Ring

Introduction

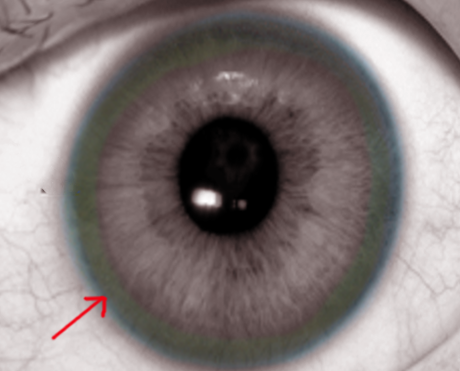

Kayser–Fleischer (KF) rings are a common ophthalmologic finding in patients with Wilson disease. Initially thought to be due to the accumulation of silver, they were first demonstrated to contain copper in 1934. KF rings are seen in most of the patients with neurologic involvement from Wilson disease. These rings are caused by deposition of excess copper on the inner surface of the cornea in the Descemet membrane. A slit lamp examination is mandatory to make a diagnosis of KF rings particularly in the early stages unless the rings are visible to the naked eye in conditions of severe copper overload. Kayser–Fleischer rings do not cause any impairment of vision but disappear with treatment and reappear with disease progression. KF rings not specific to Wilson disease alone, they are also seen in other chronic cholestatic disorders such as primary biliary cholangitis and children with neonatal cholestasis.[1][2][3][4][5]

Etiology

Kayser–Fleischer rings are dark rings that appear to encircle the iris of the eye. They are due to copper deposition in part of the Descemet's membrane as a result of liver diseases.

Epidemiology

Kayser–Fleischer rings are seen in most of the patients with neurologic involvement from Wilson disease. However, it may not be seen in approximately 5% of these patients. They are present in only 50% of the patients with isolated hepatic involvement and in pre-symptomatic patients. Kayser–Fleischer rings may be absent in patients with fulminant disease and in most children.

Pathophysiology

Kayser–Fleischer rings are caused by deposition of excess copper on the inner surface of the cornea in the Descemet membrane extending to the trabecular meshwork. Copper is deposited as a granular complex with sulfur which gives a ring its characteristic color. It is to be noted that copper is present throughout the cornea, however, due to fluid streaming, copper tends to accumulate superiorly and inferiorly, before involving the iris circumferentially. Copper can also be deposited in the lens in the anterior and posterior capsule causing sunflower cataracts which have radiating centrifugal extensions. Both Kayser–Fleischer ring and sunflower cataract do not cause any impairment of vision. Deposition of excess copper in the basal ganglia in the brain leads to the neurologic and psychiatric manifestations of Wilson disease.[6][7][8][9]

History and Physical

Wilson Disease should be suspected in all patients with the following:

- Kayser–Fleischer rings detected on routine eye exam

- A sibling or parent with a diagnosis of Wilson disease

- Unexplained and acquired Coombs-negative hemolytic anemia

- Neurological symptoms of unexplained origin

- Psychiatric disease with signs of hepatic or neurologic disease

- In persons between ages three and 55 years with unexplained serum aminotransferase elevation, chronic hepatitis with steatosis, poorly responsive autoimmune hepatitis, cirrhosis, or acute liver failure.

Age alone should not be the used as a criterion to disregard a diagnosis of Wilson disease. A few patients older than 55 years present with neurologic symptoms of Wilson disease, particularly when such symptoms were overlooked.

Evaluation

Kayser–Fleischer rings do not cause any symptoms. It is usually seen as a golden, brown ring in the peripheral cornea. It starts at Schwalbe's line and extending less than 5 mm onto the cornea. The ring may appear as greenish-yellow, ruby red, bright green, or ultramarine blue. It is almost always bilateral and appears superiorly first, then inferiorly, and then later becomes circumferential. In the initial stages, Kayser–Fleischer rings are usually seen with slit lamp examination; however, as the disease progresses they can be seen with the naked eye, particularly when the iris is lightly pigmented, and there is severe copper overload. Hence, a slit lamp examination is mandatory to make a diagnosis.

Treatment / Management

Once the diagnosis has been established, treatment is given with chelating agents. These agents bind the excess copper in the body and enhance urinary excretion. Two medications used commonly are penicillamine and trientine. Both of these drugs need to be taken orally, and treatment is usually lifelong. Agents like zinc acetate prevent excessive absorption of copper and are also used in conjunction with chelating agents, as maintenance therapy in patients who have been decoppered, and as a temporary measure in pregnancy. The patients should strictly follow a low copper diet. Patients who present with acute liver failure will need emergent liver transplant evaluation as medical treatment alone is ineffective in such patients.[10][11]

Kayser–Fleischer rings typically disappear with treatment and reappear with disease progression. When present, it a useful clinical sign to monitor treatment compliance. The rings disappear with chelation therapy over three to five years in up to 80% of patients

Differential Diagnosis

- Chronic hypertensive encephalopathy

- Embolic territorial infection

- Glioma

- Japanese Encephalitis

- Primary CNS lymphoma

- Tuberculosis meningoencephalitis

- West Nile encephalitis

Pearls and Other Issues

Wilson disease is an autosomal recessive disease where the affected organs exhibit elevated copper levels due to copper toxicity. Intestinal copper absorption is not increased in patients with Wilson disease, but the biliary excretion of copper is reduced. The reduced biliary excretion of copper is possibly due to a defect in the entry of copper into lysosomes, but the delivery of the lysosomal copper to bile is intact. Although serum ceruloplasmin is low in patients with Wilson disease, this finding is unlikely to be responsible for the copper toxicity seen in Wilson disease. The low ceruloplasmin is due to the lack of incorporation of copper into apoceruloplasmin, which has a shorter half-life than copper-bound ceruloplasmin (holo-ceruloplasmin).

Clinical symptoms of Wilson disease are rarely present before five years of age, and most untreated patients manifest with symptoms by the age of 40. Low concentration of ceruloplasmin in serum can be due to many causes, such as severe liver disease causing diminished synthesis, nephrotic syndrome, protein-losing enteropathy, and intestinal malabsorption. Normal levels of serum ceruloplasmin do not rule out Wilson disease. This is seen in at least 15% of patients with Wilson disease and is usually seen as an acute phase reactant to severe liver injury due to any cause, and in patients with elevated serum estrogen levels.

In summary, the presence of Kayser–Fleischer ring or significantly elevated hepatic copper concentration obtained via a liver biopsy and a low serum ceruloplasmin level establishes the diagnosis of Wilson disease in all cases where the diagnosis is suspected.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Kayser–Fleischer rings are a sign of Wilson disease. They are not specific to Wilson disease alone. Kayser–Fleischer rings rarely are seen in other chronic cholestatic disorders such as primary biliary cholangitis and children with neonatal cholestasis. Wilson disease is usually managed by an interprofessional team that includes an ophthalmologist, neurologist, gastroenterologist, and a hepatologist. The outpatient management is by the nurse practitioner and primary care provider.[4]

As per the American Association for Study of Liver Disease guidelines, the presence of Kayser–Fleischer rings, low serum ceruloplasmin concentration (less than 20 mg/dL), and elevated basal 24-hour urinary excretion of copper are sufficient to establish a diagnosis of Wilson disease. If Kayser–Fleischer rings are present but the serum ceruloplasmin is above 20 mg/dL, a liver biopsy is needed to make a diagnosis of Wilson disease. In the absence of Kayser–Fleischer rings, a liver biopsy with hepatic copper quantification is mandatory to confirm the diagnosis of Wilson disease. Normal urinary excretion of copper is less than 40 micrograms in 24 hours. Most patients with Wilson disease have urinary copper excretion higher than 100 micrograms in 24 hours, and the copper excretion often exceeds 1000 micrograms per 24 hours in those with fulminant hepatic failure. A hepatic copper concentration of more than 250 micrograms per gram of dry weight, accompanied by low serum ceruloplasmin and elevated basal 24-hour urinary excretion of copper establishes the diagnosis of Wilson disease. In cases where the hepatic copper content is between 50 and 250 micrograms per gram of dry weight, molecular testing (confirming homozygosity for one mutation or two mutations constituting compound heterozygosity) is required to make a diagnosis of Wilson disease. If the hepatic copper content is less than 50 micrograms per gram of dry weight, a diagnosis of Wilson disease is excluded. An elevated copper concentration alone on liver biopsy does not make a diagnosis of Wilson disease. Hepatic copper concentration may be elevated in other chronic cholestatic disorders and non-Wilsonian hepatic copper overload conditions such as Indian childhood cirrhosis, Tyrolean infantile cirrhosis, and idiopathic copper toxicosis.