Knee Dislocation

- Article Author:

- Michael Mohseni

- Article Editor:

- Leslie Simon

- Updated:

- 7/19/2020 9:09:00 AM

- For CME on this topic:

- Knee Dislocation CME

- PubMed Link:

- Knee Dislocation

Introduction

A knee dislocation is a potentially devastating injury and is often a surgical emergency. This injury requires prompt identification, evaluation with appropriate imaging, and consultation with surgery for definitive treatment. Vascular injury and compartment syndrome are dreaded complications that the clinician should not miss in the workup of a knee dislocation. Note that this is in distinct contrast to patellar dislocations, which generally do not require immediate surgical or vascular intervention.[1][2]

Etiology

High-energy trauma is usually required to cause tibiofemoral dislocation at the knee joint. To disrupt this joint, multiple concomitant ligamentous injuries and instability would also be expected. Motor vehicle collisions, sports-related injuries involving high velocity, and falls all have been implicated as causes. Posterior and anterior dislocations occur most frequently; medial, lateral, and rotatory dislocations are also possible.

Epidemiology

Knee dislocations are infrequently encountered but are potentially limb-threatening injuries. Obesity is an independent risk factor for sustaining this injury. A large number of knee dislocations can reduce spontaneously prior to clinical evaluation; hence, the diagnosis can be difficult, and the complications from the injury are easy to miss. Undiagnosed vascular injury can lead to prolonged limb ischemia and ultimately amputation.[3][4][5]

Pathophysiology

Four major ligaments help to stabilize the knee joint. These include the anterior cruciate, posterior cruciate, medial collateral, and lateral collateral ligaments. A knee dislocation would be expected to disrupt several or all of these structures potentially. As far as vascular structures are concerned, the popliteal artery is at the highest risk of sustaining insult as a result of a tibiofemoral dislocation. The artery stretches across the popliteal space and gives off several branches in a collateral system around the knee. Given its position in the popliteal space and the mechanism of knee dislocation, up to 40% of patients with a tibiofemoral disruption will sustain an associated vascular injury. Peroneal nerve injuries can also occur in greater than 20% of knee dislocation patients given the anatomic location of this nerve at the fibular neck.

History and Physical

Obtaining a thorough history is paramount in the diagnosis of knee dislocations, especially in instances where the joint has spontaneously reduced before medical evaluation. The clinician should inquire about the traumatic mechanism and if the patient noted the position of the lower leg immediately after the injury. In scenarios where the patient or emergency management services report a change in the position of the tibia relative to the femur, the examiner should assume a knee dislocation occurred and then may have spontaneously reduced to a more anatomic position. Gross instability suggested by hyperextension of the knee greater than 30 degrees when lifting the heel suggests that a knee dislocation may have occurred. In other instances, the patient may present after trauma with an obvious deformity consistent with knee dislocation, making the diagnosis more straightforward. A significant joint effusion, swelling, and ecchymosis may be present around the knee as well, which can limit examination of ligament integrity.

Distal pulses, as well as popliteal pulses, should be assessed. However, a palpable distal pulse does not suggest the absence of vascular injury. Limb-threatening vascular ischemia can result even in the presence of palpable distal foot pulses. The clinician should also assess for proper sensory and motor function though this can be somewhat limited by the pain and swelling associated with this injury.

Evaluation

The patient should be initially evaluated to determine if the prompt reduction of the knee joint is needed. Upon achieving reduction, or if the joint has already spontaneously reduced, the patient’s vascular status should undergo evaluation, including palpating pulses as well as measuring ankle-brachial index (ABI). The ABI measurement is a ratio of lower extremity perfusion (posterior tibial and dorsalis pedis arteries) and upper extremity perfusion (brachial artery). An ABI of 0.9 or greater is considered normal while an ABI less than 0.9 can be indicative of a vascular compromise. This test is just one adjunct in the evaluation of the patient with a knee dislocation. The clinician’s pulse and perfusion examination are of limited utility unless there are hard signs of vascular compromise, in which prompt case evaluation by vascular surgery is necessary. Normal pulses or ABIs do not necessarily rule out any injury, and this finding should not falsely reassure the clinician. Reports exist of popliteal artery contusion, intimal layer disruption, and delayed thrombus formation in patients with distal perfusion after knee dislocation.

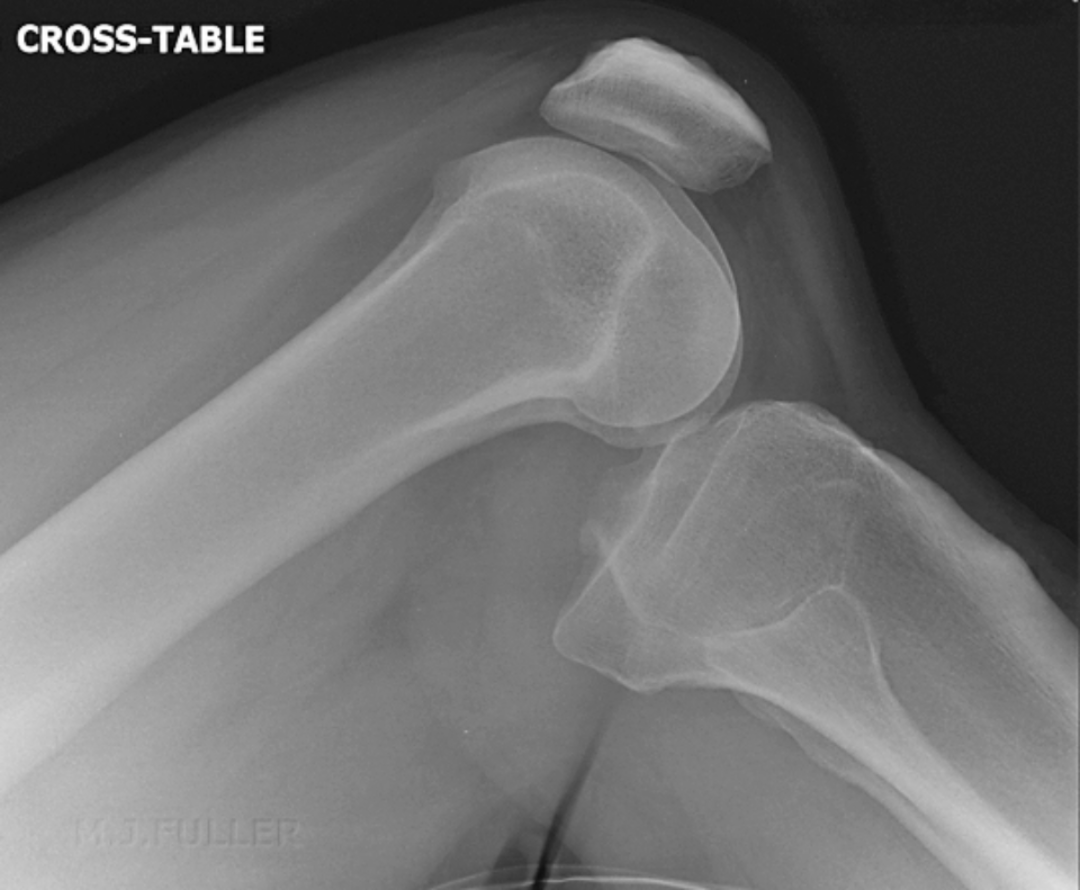

Imaging with anteroposterior and lateral radiographs can confirm the reduction of the joint and any concomitant fracture. Duplex ultrasonography, if readily available, can be used for bedside evaluation of the vasculature. Due to limitations of the vascular exam, imaging with computed tomography angiogram should be pursued in cases of asymmetric pulses, decreased ABI, or abnormal duplex ultrasound. Hard signs such as absent/weak pulses, pale or cool extremity, paresthesias, or paralysis mandate emergent vascular surgery consultation.[6]

Treatment / Management

In the patient presenting with a knee dislocation that has not spontaneously reduced, prompt reduction of the knee joint should be achieved using adequate analgesia and sedation. Procedural sedation with two providers is generally needed. The reduction itself will often require one provider to stabilize the femur while another performs traction and manipulation of the tibia. The direction of needed tibial movement will depend on the type and direction of the dislocation. Posterolateral dislocation may be difficult or impossible to reduce and will require orthopedic consultation. The providers performing the reduction should avoid excessive pressure on the popliteal fossa in case of a popliteal arterial injury.[7][1]

Once reduced, the clinician should reevaluate distal pulses and vascular perfusion. Imaging should be obtained as described above. Admission for serial vascular examinations is an option only in patients with clearly strong distal pulses, normal ABI, and normal duplex ultrasound. Otherwise, emergent vascular surgery consultation in concert with computed tomography angiogram should be pursued to rule out popliteal artery injury.

Orthopedic consultation may be necessary as an inpatient for discussion on reconstructive surgery. In cases of vascular injury, operative repair by vascular surgery may be required.

Differential Diagnosis

- Anterior cruciate ligament injury

- Femoral shaft fractures

- Knee fracture management in emergency medicine

- Medial collateral ligament injury

- Meniscus injuries

- Patellar injury and dislocation

- Patellofemoral joint syndromes

- Tibia and fibula fractures in ED

Complications

- Injury to popliteal artery and vein

- Peroneal nerve injury

- Compartment syndrome

Pearls and Other Issues

A palpable distal pulse is not adequate for the assessment of normal vascular function in this injury. Further workup and evaluation are mandatory to rule out any possible popliteal arterial insult that may have occurred during the dislocation. Any sign of vascular compromises mandates emergent vascular surgery consultation.

Delay in the diagnosis of popliteal artery injury may result in irreversible injury and ischemia, requiring above-knee amputation. Generally, any persistent ischemia greater than eight hours will necessitate amputation. Delayed thrombosis is also possible and may not present during the initial evaluation.

Other injuries that the clinician may encounter include peroneal nerve injury, a cause of foot drop. Compartment syndrome and deep venous thrombosis are among other possible complications. Associated fractures and ligamentous injuries should receive treatment as per orthopedic surgery recommendations.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Knee dislocation is a relatively common injury seen in the emergency department. Because the dislocation can be associated with a neurovascular injury that can lead to loss of a limb, an interprofessional team must manage these patients. The triage nurse must be fully aware that a dislocated knee can disrupt the vascular supply to the distal leg and hence, immediate admission and consultation with an emergency department physician are necessary. A vascular surgeon consult is in order if there is a loss of pulses in the leg, and a radiologist may be consulted to image the blood supply. Orthopedic consultation is also necessary in almost all cases. Nursing will also participate in post-procedure care, including medication administration and monitoring of vitals. For most patients who obtain prompt management, the outcomes are good. However, delay or missing a vascular injury can be associated with severe consequences. In delayed cases, even after treatment, a chronically unstable and painful knee is not uncommon.[8][9] Hence, the collaborative effort of an interprofessional team can optimize outcomes for these patients. [Level V]