Laminectomy

- Article Author:

- Martin Estefan

- Article Editor:

- Gaston Camino Willhuber

- Updated:

- 7/31/2020 2:26:46 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Laminectomy CME

- PubMed Link:

- Laminectomy

Introduction

Posterior spinal decompression is one of the most common surgical procedures to release neural structures when nonoperative treatment has failed, is usually the procedure performed degenerative conditions such as spinal stenosis, especially in middle-aged and elderly patients.[1]

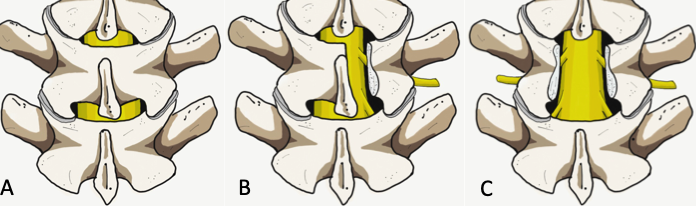

Currently, there are several techniques to accomplish posterior spinal decompression, such as open or minimally invasive laminectomy, hemilaminectomy, laminotomies, and laminoplasty. Decompression techniques classify as direct and indirect; direct procedures involve those techniques with visualization of the dural sac during the surgery such as laminectomy. On the other hand, indirect decompression takes place without dural sac visualization. Laminectomy alone or associated with fusion is one of the most common procedures performed by a spinal surgeon.[2]

Anatomy and Physiology

To understand the principles of laminectomy, proper knowledge of the posterior vertebral arch and laminae anatomy are imperative.

The laminae belong to the posterior vertebral arch, extended medially from the base of the spinous process to the junction between the superior and inferior facet joints, acting as a stabilization structure of the spine in association with the facet joint and also as a spinal cord and nerve root protective layer. The laminae general anatomy consists of a superior and inferior border, an anterior surface in contact with the medullary canal and a posterior surface that serves as erector spinae muscles attachment. The shape and thickness of the laminae vary according to the anatomical region. Laminar height tends to decrease from C2 to C4 and then increases towards a peak at T8. From T9 to L4 tends to decrease in height and increases in length having at L5 the lowest lumbar height, on the other hand, from cervical to lumbar, laminae width decreases progressively up to the narrowest at T4 in the thoracic region and then increase steadily to reach the widest at L5.

Regarding the thickness, it increases from cervical to lumbar regions.[3]

A better understanding of the laminae anatomy in different regions of the spine may improve surgery success and avoid iatrogenic complications such as nerve root or spinal cord injury.

Indications

The main indication for laminectomy is the presence of spinal canal stenosis, narrowing of the spinal canal has multiples etiologies such as congenital, metabolic, traumatic or tumoral, however, degenerative stenosis is the most common cause. Spinal stenosis can also be classified according to Wiltse in central stenosis, lateral recess, foraminal and extraforaminal stenosis.[4] Also, Lee et al. classified lateral region into three zones of nerve root compression: entrance zone (lateral recess), mid zone (foraminal region) and exit zone (extraforaminal region) in order to clarify anatomy and surgical strategy.[5] Laminectomy is especially effective for the treatment of central and lateral recess stenosis.

Central stenosis is the most common, and the main symptom is neurogenic claudication, which includes pain, tingling, or cramping sensation in the lower extremity. On the other hand, lateral recess, foraminal and extraforaminal stenosis may cause radiculopathy, patients with central stenosis may experience more symptoms in standing position and during walking and pain is usually relieved with leaning forward or in sitting position. In cases of central stenosis, straight leg raising and femoral nerve stretching test are usually normal.

When symptoms derived from stenosis do not respond to conservative treatment, surgical management such as decompression with or without fusion is usually a consideration.

Fusion techniques are required when stenosis is associated with spinal instability, degenerative or isthmic spondylolisthesis, kyphosis or scoliosis, as laminectomy alone may increase the risk of spinal instability in these conditions.[6] However, in cases of low-grade degenerative spondylolisthesis, the literature exhibits variable results regarding the risk of instability after laminectomy alone, some studies support fusion in cases degenerative spondylolisthesis.[7] On the other hand, Wang et al. in a recent meta-analysis found no increased risk of instability after laminectomy, especially in patients without predominant symptoms of mechanical back pain and after minimally invasive procedures.[8]

Other important indications for laminectomy are primary or secondary tumors, infection (peridural abscesses), trauma (fractures that compromise the spinal canal) and stenosis associated with the deformity.

Contraindications

- Spinal instability (is a contraindication for laminectomy without associated fusion technique)

- Degenerative or isthmic spondylolisthesis (relative contraindication)

- Severe scoliosis (relative contraindication)

- Severe kyphosis (relative contraindication)

Equipment

- Standard radiolucent table with spinal frames and foams pads

- C-arm to localize level and minimize skin size incision

- Laminectomy instrument set (bone cutting rongeurs, high-speed burr, Kerrison rongeurs, forceps, ball tip, angled spatula spreader, bayonet-shaped curettes, hollow probes, tubular retractors and dilators for MIS approaches)

Personnel

- No additional Staff OR personnel is required; usually, one or two spinal surgeons, registered nurse staff, and anesthesiologist.

- Neuromonitoring is usually a recommendation in cervical or dorsal laminectomies, and lumbar cases when there is an increased risk of nerve injury.

Preparation

Laminectomy is performed with the patient in the prone position on a support frame with foam pads for nipples and ASIS (anterior superior iliac crest spine) leaving the abdomen free, avoiding abdominal pressure decreases epidural venous pressure and therefore, surgical site bleeding.

Arms are positioned at 90 degrees abduction and flexion to prevent axillary nerve injury.

Technique

Laminectomy can be performed through a traditional open approach or with a minimally invasive technique.

The traditional open approach requires a posterior midline incision (3 to 4 cm in length for single level), subperiosteal dissection along spinous processes to detach and retract paraspinous muscles from the spinous processes medially to the lateral laminar border avoiding damage of the facet joint. Spinous processes may be resected along with dorsal laminae to expose ligamentum flavum with bone cutting rongeur or a burr, resection of ligamentum flavum is possible with Woodson elevator and spatula, medial facetectomies can be performed to decompress the lateral recess, and foraminal region can is reachable with Kerrison rongeurs. Use of a ball tip or angled probe help to assess foraminal size. Great care is necessary to avoid damage to pars interarticularis and more than 50% of the facet joint to decrease the risk of instability. The decompression procedure is usually complete upon confirmation of the dural sac, exiting and descending nerve roots.

Minimally Invasive Surgical (MIS) techniques include laminotomy and microendoscopic laminotomy with tubular retractors. Contemporary literature supports these procedures resulting in better preservation of posterior musculature, decreased intraoperative bleeding, and postoperative pain.[9][10]

Even though MIS approaches may have some early outcome advantages over open procedures, the economic value and cost-effectiveness of MIS require further investigation.

A recent systematic review compared conventional laminectomy with three different techniques that avoid the removal of the spinous process (unilateral laminotomy, bilateral laminotomy and split spinous process laminotomy). A decreased postoperative back pain for bilateral laminotomy and split spinous laminotomy was found, however, there were no observable clinically significant differences. Further, there was no difference in terms of hospital length of stay, operative time, and complications of these techniques compared to conventional laminectomy.[11]

Complications

Laminectomy is a relatively safe procedure, with a low complication rate. Related-technique complications are associated with the underlying structures covered by the laminae, being the dural sac tear and nerve roots injury the most commons. These complications occur more often in elderly patients due to the fragility of the dural sac. Also, the severity of compression could be a factor that increases the rate of a dural tear; the most common risk factor for dural tear is the reoperation due to the presence of scar tissue.[12]

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak from dural sac tear may cause dizziness, painful orthostatic headache, or thunderclap headache. Nonsurgical management of CSF leaks includes bed rest, caffeine, or acetazolamide to alleviate symptoms. Surgical intervention with direct dura mater repair or dural patching can be performed in cases of tear injury when it is feasible.

Reports exist of surgically induced spinal instability, especially when laminectomy was compared with unilateral laminotomy and in cases of extensive posterior laminectomy.[13][14] This complication is avoidable by preserving the pars interarticularis and at least two-thirds of lumbar or fifty percent of cervical facet joints.[15]

Postoperative wound infection and wound dehiscence are other complications to consider, the presence of wound erythema, increased pain or swelling may raise the suspicion of wound infection.

Clinical Significance

Laminectomy is one of the most commons procedures performed among spinal surgeons for the treatment of spinal stenosis. This technique, correctly performed, correlates with symptomatic improvement and early recovery with relatively low complication rates. Even when the benefits of surgical versus nonsurgical treatment in lumbar stenosis has not been proven [Level I], laminectomy remains an effective surgical technique for a variety of conditions affecting the spinal canal such as tumors, epidural abscess, and spondylotic myelopathy.[16]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Laminectomy is among the most common procedures performed by spinal surgeons to decompress the spinal canal in various conditions. Preoperative and postoperative patient care is crucial to improve outcomes of laminectomy. General practitioners, nurses, and pharmacists should advise the patient to change lifestyle, such as weight control and stop smoking. Making referrals to other professionals is essential when concomitant and associated pathologies could be present. All involved members of the interprofessional team need to communicate across interprofessional lines to achieve optimal outcomes. [Level V]

Complete comprehensive preoperative planning requires assessment. It is important to carefully document neurological status before surgery and develop correct and complete operative consent describing the magnitude, scope, and detailed complications of the surgery, as well as detail alternatives considering nonoperative management. The nurse plays a role during the pre-operative preparation of patients undergoing spine surgery. The nurse assists the clinician during the procedure and helps with the proper positioning of the patient. The nurse monitors the patient's vital signs before, during and, after the procedure. If there are any untoward changes in the patient's observations, the nurse should immediately alert the clinician and document the findings in the patient's medical records. The nurse should counsel patients appropriately about their care plans and ensure that the patient understands all components of valid consent. The best possible outcome for patients undergoing laminectomy could only be fostered through clear and efficient communication and collaboration among the members of the interprofessional team. [Level V]

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

The role of the nurse in the postoperative period should include finite management of intravenous fluids, foley catheter care until ambulating, administering antibiotics, pain control, wound/dressing care, encouraging patient ambulation, and advance diet when appropriate.

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Monitoring

Postoperative patient monitoring is important for recognizing some early complications, especially CSF leakage from dural sac tear, it is important to evaluate the wound looking for some suggestive signs such as wound bulging, or CSF sinus. Additionally, clinical signs of CSF leakage such as headache, dizziness should raise alert from a possible complication.

The presence of erythema, increased pain, or swelling may raise the suspicion of wound infection.