Anatomy, Thorax, Heart Left Anterior Descending (LAD) Artery

- Article Author:

- Ibraheem Rehman

- Article Author:

- Connor Kerndt

- Article Editor:

- Afzal Rehman

- Updated:

- 7/27/2020 9:20:40 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Anatomy, Thorax, Heart Left Anterior Descending (LAD) Artery CME

- PubMed Link:

- Anatomy, Thorax, Heart Left Anterior Descending (LAD) Artery

Introduction

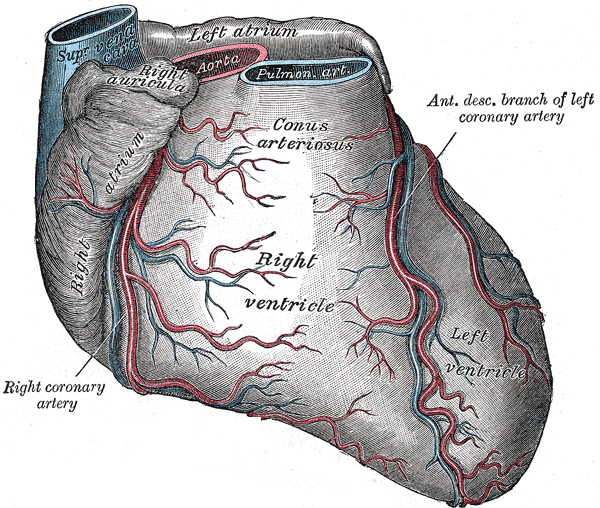

The heart is a muscular pump that provides the force necessary to circulate blood throughout the body. Cardiac muscle requires blood flow to function. This flow is provided by the coronary arteries. The right coronary artery arises from the right aortic sinus of the aorta, just above the aortic valve. Similarly, the left coronary artery, also known as the left main coronary artery, arises from the left aortic sinus. The left main coronary artery divides into the left anterior descending artery that supplies the anteroseptal wall of the heart and the circumflex coronary artery that supplies the posterior and lateral portions.

Structure and Function

The LAD carries almost 50% of the blood carried by the coronary circulation. During systole, the heart muscle squeezes over the perforating arteriolar branches and causes complete cessation of flow. All coronary flow, therefore, occurs during diastole when the pressure from the cardiac contraction is not obstructing the blood flow. Therefore, the coronary flow is dependent on diastolic blood pressure. Just like any other capillary bed, the coronary circulation is controlled by local autoregulation mediated by demand dependent arteriolar dilatation.[1][2]

Structure

The coronary arteries run on the epicardial surface of the heart to avoid being compressed by the cardiac muscle when it contracts. The left anterior descending artery (LAD) is the largest coronary artery runs anterior to the interventricular septum in the anterior interventricular groove, extending from the base of the heart to the apex. The LAD gives two sets of branches. The septal branches perforate the interventricular septum to supply the anterior two-thirds of the septum. These are numbered as S1, S2, onwards starting from base to the apex. The second set of branches course over the anterior aspect of the left ventricle and are called diagonal branches. These are also numbered D1, D2, onwards starting from proximal to distal. Around the apex, the LAD anastomoses with the terminal branches of the posterior descending artery which is usually a branch of the right coronary artery.

Depending upon the length of the LAD, the LAD is classified into four types: type-I – does not supply the left ventricular (LV) apex, type-2 – supplies part of the apex, the rest being supplied by the right coronary both, type3 – supplies the entire apex, and type-4 – supplies the apex and >25% of the inferior wall (wrap around).

A small left conus branch usually arises from the proximal LAD and anastomoses with its counterpart from the right coronary artery around the aortic conus and also with the vasa vasorum of the aorta and the pulmonary artery.

Usually, a couple of small right ventricular branches also arise from the LAD supplying small parts of the anterior right ventricle.

Multiple anastomoses exist between the coronary arteries. The terminal LAD anastomosis with the terminal branches of the posterior descending artery (PDA) in the posterior interventricular groove about 90% of the time. In 10% of the cases, no such anastomoses exist. Within the interventricular septum, septal branches of the LAD freely anastomose with the septal branches of the PDA. However, the flow in all of these anastomoses is small and does not suffice in case of sudden occlusion of a parent vessel. If the parent vessel occludes slowly, often the anastomoses can gradually enlarge to provide meaningful flow.

The LAD and its branches are epicardial and give off “end-arteries,” in effect arterioles that perforate the myocardium to supply it.

Embryology

The origin of the coronary arteries is not entirely clear. Coronary arteries may arise from the epicardial layer or the sub-epicardial vessel plexus.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Vasa Vasorum are tiny blood vessels that supply blood to the coronary vessels themselves. The lymphatics of the heart drain back along the coronary arteries, emerge from the fibrous pericardium along with the aorta and the pulmonary trunk and empty into the trachea-bronchial lymph nodes and mediastinal lymph trunks.

Nerves

Sympathetic fibers from the cardiac plexus innervate the coronary arteries. The left coronary plexus arises mainly from the left half of the deep part of the cardiac plexus and accompanies the left coronary artery branches to supply the left atrium and ventricle.

Physiologic Variants

Myocardial Bridging: Although coronary vessels run over the epicardial surface of the heart, sometimes the artery courses intra-myocardial under a muscle “bridge.” Bridging is found in 0.5% to 40% individuals when identified clinically and 15-85% on autopsy studies.[3]

Absent Left Main: In some cases, the left main coronary artery is absent, and both the LAD and the circumflex arteries arise from a single cloacal opening. In other cases, these two arteries arise from completely separate openings directly from the aorta.

Coronary Fistulae: Coronary fistulae are rare in adults, but account for 50% of pediatric coronary anomalies. A fistula between a coronary artery and the cardiac cavity is called a coronary-chimeral fistula, that between a coronary artery and vein is called an arterio-venous fistula. Most fistulae are congenital. Acquired ones are usually iatrogenic or traumatic.

Anomalous Origin: Anomalous origin of left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery is a rare malformation (incidence of 0.25–0.50%) in children with abnormal cardiac development leading to a mortality rate of 90% in unoperated infants.[4]

Surgical Considerations

Given the importance of LAD for coronary blood flow, during coronary artery bypass surgery, surgeons often try to bypass this with the best possible graft, usually using the left internal mammary artery (LIMA). During such surgery, LIMA is mobilized from the chest wall keeping its origin intact. Side branches are tied off, and the end is anastomosed to the LAD. LIMA to LAD grafts are very durable.

Clinical Significance

The LAD is the largest coronary artery. Atherosclerosis or thrombotic occlusion of this vessel causes myocardial infarction involving large areas of the anterior, septal and apical portions of the heart muscle leading to serious impairment of cardiac performance. For the same reason, during revascularization by percutaneous or surgical methods, it is important to restore the flow in the LAD.[5][6] Infarcts involving LAD occlusion frequently involve the apex. This can be accompanied by the formation of clots in the apex. These clots can embolize cause stroke or systemic embolism.