Lumbar Degenerative Disk Disease

- Article Author:

- Chester Donnally III

- Article Author:

- Andrew Hanna

- Article Editor:

- Matthew Varacallo

- Updated:

- 4/13/2020 6:59:03 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Lumbar Degenerative Disk Disease CME

- PubMed Link:

- Lumbar Degenerative Disk Disease

Introduction

Between each vertebral body of the spine are pads of fibrocartilage-based structures that provide support, flexibility, and minor load-sharing known as the intervertebral discs. These are primarily composed of two layers: (1) a soft, pulpy nucleus pulposus on the inside of the disc and (2) a surrounding firm structure known as the annulus fibrosus. A disruption of the normal architecture of these round discs can lead to a disc herniation or a protrusion of the inner nucleus pulposus, possibly applying pressure to the spinal cord or nerve root and resulting in radiating pain and specific locations of weakness. Slightly more than 90% of herniated discs occur at the L4-L5 or the L5-S1 disc space, which will impinge on the L4, L5 or S1 nerve root. This compression produces radiculopathy into the posterior leg and dorsal foot.

If the disc injury progresses to the point of neurologic compromise or limitations with activities of daily living, then surgical intervention may be required to decompress and stabilize the affected segments. In the absence of motor deficits, a nonoperative course of analgesia, activity modification, and injections should be tried for several months. The surgical results for the primarily sciatic pain that has failed conservative treatment are predictable and favorable.[1][2][3]

Etiology

Disc degeneration is directly correlated with increasing patient age. Interestingly, while it is thought that men likely start this degeneration almost ten years earlier than women, women with disc degeneration are likely to be more susceptible to the effects (e.g., malalignment, instability).[4][5][6]

Traditionally, dating back to the early 1990s, the traditional views regarding the etiologies of disc degeneration focused on environmental exposures such as smoking, vehicular vibration, and occupation. More recent research has highlighted the genetic components associated with disc disease and shifted the paradigm away from the aforementioned social, occupational, and environmental factors.

The contemporary general consensus advocates the importance of these genetic factors as the most important predictors of disc degeneration, and the environmental factors are recognized as additional, minor contributors to disease onset. The effects of smoking also have been questioned with more recent research only finding weak correlations with cigarette use and disc disease. Similarly, while occupational aspects (e.g., heavy lifting, forceful bending) may have some contributions to lumbar degeneration, it is now thought that socioeconomic factors likely confound these studies, and occupational exposure is, at most, a minor contributor to disc disease.

Epidemiology

Most intervertebral disc degenerations are asymptomatic, making a true understanding of the prevalence difficult. Additionally, due to the lack of uniformity in the definitions of disc degenerations and disc herniations, the actual prevalence of the disease is difficult to review across multiple studies. In a meta-analysis of 20 studies evaluating the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of asymptotic individuals, the reported disc abnormalities at any level were: 20% to 83% for a reduction in signal intensity, 10% to 81% for disc bulges, 3% to 63% for disc protrusion (versus 0% to 24% for disc extrusion), 3% to 56% for disc narrowing, and 6% to 56% with annular tears. This study supports that the mere incidental finding of disc disease is common and should not necessitate specialist evaluation in the absence of pain or limitations.[7][8]

Pathophysiology

The radiation of back pain associated with disc disease is thought to be due to the compression of the nerve roots in the spinal canal from either one or a combination of, the following elements

- Disc herniation material (i.e. herniated nucleus pulposus, HNP)

- Varying degrees of HNP is recognized, from disc protrusion (annulus remains intact), extrusion (annular compromise, but herniated material remains continuous with disc space), to sequestered (free) fragments

- HNP material predictably is resorbed over time, with the sequestered fragment demonstrating the highest degree of resorption potential

- In general, 90% of patients will have a symptomatic improvement in radicular symptoms within 3 months following nonoperative protocols alone

- Hypertrophy/expansion of degenerative tissues

- Common sources include ligamentum flavum and the facet joint. The facet joint itself undergoes degenerative changes (just like any other joint in the body) and synovial hypertrophy and/or associated cysts can compromise surrounding nerve roots.

In a 2010 study by Suri et al. 662% of 154 consecutive patients presenting with new lumbar disk herniation noted spontaneous symptoms compared to just 26% who reported the symptoms starting after a specific household task or seemingly common non-lifting activity. Contrary to popular belief, fewer than 8% reported acute sciatica after heavy lifting or physical trauma.[9]

Histopathology

The many tiny blood vessels surrounding the spinal cord and nerve roots are paramount to delivering nutrition, oxygen, and chemomodulators. The compression of these structures limits the ability of these vessels to deliver vital nutrients, resulting in an ischemic effect of the structure. The subsequent inflammation from intervertebral disc compression results in (ischemic) pain along the path of this nerve root. This nerve compression from the disc causes an increase in cytokines, TNF-alpha, and the recruitment of macrophages. Interestingly, the extent of the histologic changes within the intervertebral disc has a positive correlation with body mass index, indicating that those with obesity may be more prone to degeneration.

History and Physical

Patient history should focus on the timeline of pain, radiation of pain, and inciting events. Careful attention to prior episodes of trauma should be noted. Classically, patients complain of pain radiating down both buttocks and lower extremities. It is helpful to determine if the pain is localized to the lower back or if there is radiation into the leg(s). A presentation of radiating pain correlates with canal stenosis. Radiating pain as the main issue has a much more predictable surgical outcome compared to a presentation of non-specific lower back pain that likely is related to muscle fatigue and strain. A mechanical component to the back pain (i.e., the pain only with certain movements) may indicate instability or a degenerative pars fracture. It also is important in any evaluation of extremity issues to inspect circulation, as vascular claudication may mirror or mimic the neurogenic issues.[10]

An evaluation of the patient walking is critical to better assess the daily impact the pain/deficit is causing. Having the patient arise from the chair, walk on his or her heels and toes, and then sit on the examination table for testing of strength, reflex, and straight leg testing is one systematic order. The gait assessment should include ruling out a Trendelenburg gait, which can reveal an underlying weakness in the gluteus medius, innervated by the L5 nerve root.

All physical examinations will include the evaluation of the neurologic function of the arms, legs, bladder, and bowels. The keys to a thorough exam are organization and patience. One should not only evaluate strength, but also sensation and reflexes. It is also important to inspect the skin along the back and document the presence of tenderness to compression or any prior surgical scars.

The straight leg raise (SLR) test consists of a supine patient having his/her fully extended leg passively stretched from 0 to about 80 degrees. The onset of radiating back pain in either leg supports a diagnosis of a stenotic canal. A herniation compressing the L5 nerve root will present as a weakness of ankle dorsiflexion and an extension of the great toe. This deficit also may diminish the Achilles tendon reflex. L4 radiculopathy may present with weakness at the quadriceps and a decreased patellar tendon reflex.

Documentation is paramount, as these initial findings likely will be used as a baseline for all future evaluations.

Wadell Signs

A comprehensive examination should also include ruling out non-organic causes of low back pain/symptoms. When the clinician suspects potential malingering, consideration should be given to the following:

- Nonspecific description of symptoms or inconsistency, including superficial/non-anatomic sites of tenderness on exam

- Pain with axial load/rotational movements

- Negative SLR with patient distraction (one approach includes having the patient sitting in a chair and reproducing the SLR "environment")

- Non-dermatomal patterns of distribution of symptoms

- Pain out of proportion on the exam

Evaluation

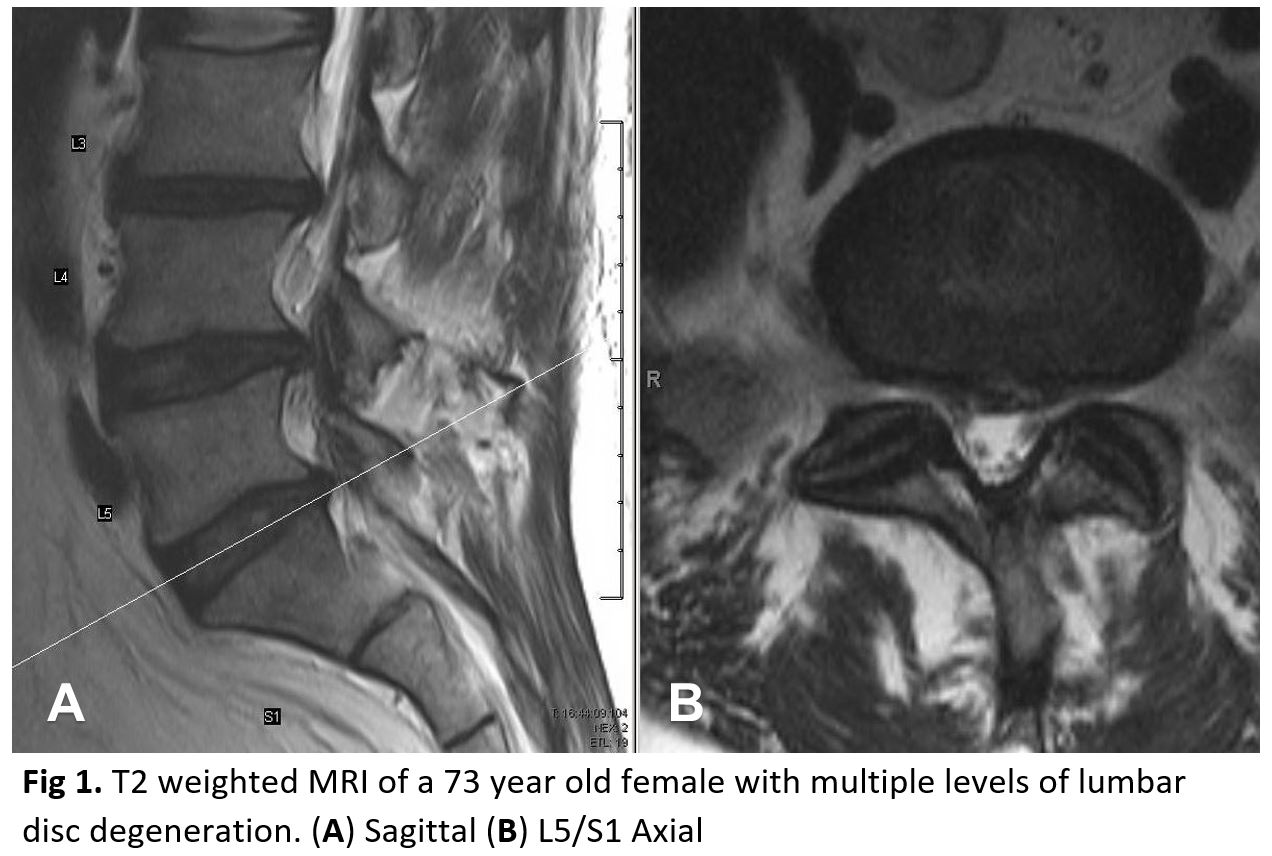

Evaluation of patients with low back pain typically includes anterior-posterior (AP) and lateral radiographs of the impacted area. Some physicians will obtain radiographs of the entire spine. An MRI should not be ordered at the initial presentation of suspected acute disc herniations in patients lacking “red flags,” because these patients will initially trial a 6-week course of physical therapy and frequently improve. An MRI likely is an unnecessary financial and utilization burden in the initial presentation. If at follow-up the symptomology is still present, then an MRI can be obtained at that time. The focus should be directed to the T2 weighted sagittal, and axial images as these will illustrate any compression of neurologic elements (Figure 1). Over time, both symptomatic and asymptomatic disc herniations will decrease in size on MRI. The finding of disc disease (degeneration or herniation) on MRI does not correlate with the likelihood of chronic pain or the future need for surgery.[11][7]

Treatment / Management

In the setting of “red-flags,” aggressive diagnosis and likely surgical options should be explored. Examples of these red flags include:

- Cauda equina syndrome (issues controlling bowel/bladder, difficulty starting urination)

- Infection (high suspicion in IV drug user, history of fever, nighttime chills)

- Tumor suspected (known history of cancer; new-onset weight loss)

- Trauma (fall, assault, collision)

Fortunately, the majority of patients will improve without surgical treatment. A course of at least 6 weeks of physical therapy with an emphasis on core strengthening and stretching should be attempted. Non-surgical intervention includes modification of the activity that may exacerbate the pain, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs), and epidural injections. Epidural injections may provide moderate, short-term relief of pain due to disc herniations; but the literature regarding the usefulness of injections for chronic non-radiating back pain is less certain. Certainly, the literate does not advocate against injections as a non-operative treatment option.

Unfortunately, many patients do not respond to conservative treatment. With a failed conservative course the patient has three options: (1) continued pain, (2) complete avoidance of activities that elicit pain, or (3) surgical intervention. Again, the surgical options for disc herniations, as well as degenerative spinal stenosis, should be reserved for those with either neurologic deficits, degenerative spondylolisthesis, or pain limiting daily functions.

One of the most cited guides on the outcomes of surgical versus conservative management for lumbar disc herniations comes from the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT). In their report, patients electing for surgery had better outcomes at 3 months, years, and 4 years compared to patients who did not elect surgery. The literature regarding the optimal surgical procedure, approach, and roles for decompression/instrumentation continues to expand. Literature shows that a traditional open surgery compared to a microdiscectomy is broadly similar in outcomes and effectiveness. In regards to the amount of disc removed during a discectomy, while a “limited” discectomy provides better pain relief and patient satisfaction compared to a subtotal discectomy, they have a higher risk of repeat herniations. Patient outcomes and satisfaction are similar in repeat/revision micro discectomies as compared to their initial discectomy. The operation, at times, requires overnight hospitalization; but frequently these surgeries are designed to be outpatient procedures.

It is important for the patient to understand that while surgical intervention has favorable outcomes for relieving radicular pains, the results are less predictable for non-radiating lower back pain.[12][5][13]

Differential Diagnosis

- Cauda equina syndrome

- Muscle spasm

- Spinal cord tumor

- Spinal infection

- Spondylolisthesis

- Spondylolysis

Complications

- Bleeding

- Recurrence of disease or symptoms

- Infection

- Worsening neurological deficits

- Failed operation

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

- Ambulation and resumption of exercise is key

- Pain control

- Maintain a healthy weight

Pearls and Other Issues

Historical treatment options for disc herniations include intradermal injections (chemonucleolysis) with the goal of de-innervating the receptors of pain at the disc. The advancement of disc degeneration and the various other complications has resulted in this treatment falling out of favor. Future studies on the inhibition of molecular mediators of degeneration are promising. Similarly, while it is known that tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha is a major contributor to the degeneration and pain associated with disc disease, placebo-controlled, randomized, controlled studies with TNF-alpha inhibitors showed negative outcomes in those treated patients, which shows that more research is needed to determine the best molecular strategies for treatment.

In regards to microdiscectomy postoperative rehabilitation, one study showed superior results when neuromuscular exercise programs were started 2 weeks post-surgery (compared to those starting at the traditional 6-week mark). Furthermore, at 4 to 6 weeks postoperatively, evidence shows that intensive exercise programs result in the more rapid short-term improvement of function as well as a return to work when compared to mild intensity programs. Most importantly, these studies show that the more aggressive and sooner-onset therapies did not alter the rates of re-herniation or reoperation.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Lumbar disc disease carries enormous morbidity leading to disability and a poor quality of life. Many patients are mistakenly led to the belief that the disorder can be cured by surgery, sadly failed surgeries and residual neurological deficits are common. There is a whole industry that focuses on low back pain offering sham therapies for people with lumbar disc disease. The key is patient education. The nurse and the physical therapist are in a prime position to educate the patient about changes in lifestyle that can lead to significant improvement and a better quality of life. Weight loss must be encouraged, the patient must enter an exercise program and eat a healthy diet. The pharmacist should encourage cessation of smoking and abstain from alcohol. More importantly, the patient should be discouraged from seeking supplements that have no benefit. In the majority of patients with lumbar disc disease, a positive change in lifestyle leads to a marked improvement in symptoms.[14][15] (Level v)

Outcomes

The majority of patients who are treated conservatively do have a good outcome provided they change lifestyle. For those who undergo surgery, the outcomes do vary from poor to fair. In fact, poor results are universal. Many outcome studies have been misrepresented because they have been published by the surgeon or the orthopedic manufacturer or sponsorer. The long-term reduction is radicular pain is seen in some patients, but the numbers vary from 30-60%. For those who do not undertake changes in lifestyle, the recurrence of symptoms is very common.[16][17] (level V)