Lung Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Infections

- Article Author:

- Arian Bethencourt Mirabal

- Article Editor:

- Gustavo Ferrer

- Updated:

- 7/2/2020 7:44:36 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Lung Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Infections CME

- PubMed Link:

- Lung Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Infections

Introduction

Following the discovery of mycobacterium tuberculosis by Robert Koch in 1882, several other mycobacteria were identified as well. However, they were not recognized as causing disease in humans until the 1980s. Non-tuberculosis mycobacteria (NTM) are ubiquitous in the environment. They are responsible for opportunistic infections that affect not only the immunocompromised host but also an immunocompetent individual. The incidence of the disease from NTM has been gradually increasing worldwide, becoming, in recent years, an emerging public health problem.[1][2][3] In 2007, the American Thoracic Society [ATS] published a clinical guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of non-tuberculous mycobacteria.[4] This was chiefly due to previous controversial experts’ opinions on how to establish the diagnosis and treatment of the disease. Therefore, current guidelines continue to be based on both experts’ opinions, and some new guidelines; but no universal recommendations exist. With new medical advances based on molecular microbiology, the diagnosis of most NTM is not only more precise but much faster than before. In this activity, we provide an in-depth look at how NTM present, the clinical features and methods to make a rapid diagnosis and identification of NTM. An interprofessional team approach based on the most up-to-date literature on the topic is vital if one wants to improve outcomes.

Etiology

M. tuberculosis, M. leprae, and NTM are all related to the genus mycobacteria. Runyon identified the non-tuberculous mycobacteria in the 1980s. He was able to identify the other mycobacterial species based on their pigmentation changes in the presence or absence of light (photochromogens, scotochromogens, non-chromogenic) and growth characteristics (slow versus rapid).[5] One particular characteristic of the mycobacteria is their slow rate of growth. However, NTM further sub-classifies into rapidly-growing or slow-growing organisms. The former usually grows in seven days, whereas the latter usually takes up to three weeks.

During the last decade, the use of more advanced molecular and genetic methods for microorganism identification has resulted in the previous Runyon classification getting replaced. Today, the number of identified NTM species has reached more than a hundred, with around fifty that correlate with a lung infection.[4] However, the most commonly occurring NTM that affects humans includes Mycobacteria avium, M. ansasii, and M. abcessus.

Epidemiology

The epidemiology of NTM lung infections has been challenging to determine, due to the following:

- In many countries, it is not mandatory to report the condition to the public health departments

- The differentiation between infection and disease is often difficult.

- The diagnosis tests are not always available in all institutions

- Follow up is not precise

In the 1980s, U.S. laboratories reported an estimated prevalence of NTM infection of 1 to 2 cases per 100000 population[6]. The annual prevalence increased among men and women in Florida (by 3.2% per year and 6.5% per year, respectively), and among women in New York (by 4.6% per year), but there was no significant increase seen in California. The annual prevalence of NTM pulmonary diseases in U.S. Medicare beneficiaries (all persons 65 years of age and older) increased from 20 per 100000 in 1997 to 47 per 100000 in 2007.[7]

Studies since the 1950s from Czechoslovakia, Wales, Ireland, Australia, and the United States have reported increases in the incidence and prevalence of NTM lung infections. In Queensland, Australia, where NTM is reportable, the incidence of clinically significant pulmonary disease rose from 2.2 per 100000 in 1999 to 3.2 per 100000 in 2005.[8]

Finally, while the prevalence and incidence of NTM pulmonary disease have been increasing through the years, not only in the U.S. but also around the world, this epidemiological variation has not been explained. New radiological advances, especially resolution chest computed tomography (CT) scanning, improved diagnosis, and an increase in chest screening may be important factors responsible for these epidemiological observations.

Pathophysiology

All the relevant NTM become acquired via inhalation of infected aerosolized droplets. Living in close quarters, coughing, and not using a facial mask are risk factors for transmission. Advanced age, immunosuppression, and use of corticosteroids are all risk factors for acquiring these organisms. Once the organisms enter the individual, they usually settle in the lower airways; in some cases, the bacteria incite an inflammatory reaction with an influx of lymphocytes. The resulting release of cytokines and other mediators can lead to an infectious process that presents as pneumonia.

History and Physical

NTM isolation has always been controversial among physicians; this is because the bacteria lives in the ambient, making it very difficult to differentiate colonization versus infection in sterile sputum. So, it is indispensable to achieve the diagnosis of NTM by integrating clinical, radiological, and microbiological aspects. Non-tuberculosis mycobacteria have a slow growth process, resulting in a considerable time to infect the lungs. Sometimes, this particular factor, along with a low index of clinical suspiciousness, could result in either misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis. Clinical manifestations are similar to tuberculosis lung infection. These could include respiratory symptoms such as cough, dyspnea, increased sputum production, and systemic manifestations such as low-grade fever, malaise, and weight loss. The duration of symptoms may vary from a few days to a few weeks. The physical features are not specific and can mimic any infectious process of the lungs.

Evaluation

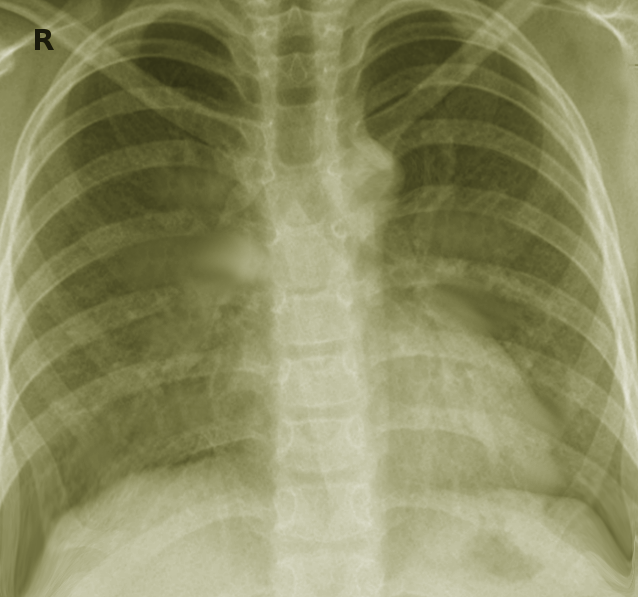

Radiological findings

As with other lung infections, radiological images are crucial for the correct diagnosis of the disease. However, unlike other lung diseases, non-tuberculosis mycobacteria have characteristic lung presentations. The two major radiological patterns of NTM lung infection are fibro-cavitary and nodular bronchiectatic pattern.[1] The fibro-cavitary radiological pattern resembles tuberculosis lung infection. It presents with cavities with areas of increased opacity, mostly located in the upper lung. On the other hand, the nodular bronchiectatic pattern characteristically shows multilobar bronchiectasis, primarily located in the middle and lower lung fields, with small nodules seen on images. This pattern predominantly presents in women smokers without previous lung conditions. Finally, there is a high prevalence of patients with bronchiectasis in patients with NTM lung infection. A recent study demonstrated that the prevalence of NTM infection in patients with bronchiectasis was 9.3%.[2] Clinicians must be aware that NTM lung infection could present with bronchiectasis on radiological images.

Laboratory diagnosis

The isolation of non-tuberculosis mycobacteria in human specimens can be challenging. Since the bacteria can is present in the environment, especially in water sources, a positive test in a sputum specimen could produce a false-positive result. Also, the NTM species from the environment that have colonized in the airway could lead to contaminant specimens, contributing to a falsely positive test result with a poor positive predictive value. Hence, current guidelines recommend that a collection of three early morning sputum specimens be obtained on three different days to achieve an accurate diagnosis of non-tuberculosis mycobacteria lung infection.[1] The methods used for acid-fast bacilli stain require the carbol fuchsin stain (Ziehl-Neelsen or Kinyoun method) and the fluorochrome procedure (auramine O alone or in combination with rhodamine B).[3][4] However, the mentioned stain methods cannot discriminate between tuberculosis versus non-tuberculosis mycobacteria.

Nuclei-acid amplification (NAA) is the most accurate test for identifying mycobacterial strains. Culture remains the test of choice for NTM laboratory confirmation. There are two media used for the culture: solid media or liquid media. Solid media includes either egg-based media, such as the Löwenstein-Jensen medium, or agar-based media such as Middlebrook 7H10 and 7H11 media. Solid media allows the visualization of morphologic, grown rate, and species characterization. The liquid media system is more sensitive but is more prone to contamination by other micro-organisms and bacteria overgrowth.

NTM identification

The treatment of non-tuberculosis infection is specific and different for every particular NTM species. Making a correct identification of the species is the main factor of successful treatment. The most accurate NTM identification method is via gene sequence. Sequencing the 16S rRNA gene allows for the correct identification and discrimination between species. However, species-level identification may need several gene sequences and more complex methods. Only specialized laboratories dedicated to the identification of species-levels by using different gene sequences can perform this test. The matrix-associated laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) method has increasingly employed for the identification of NTM. This method is identifying target bacteria by comparing mass spectral pattern molecules specific to NTM.

Drug Susceptibility

When NTM are cultured, drug susceptibility tests are always conducted to assist physicians with the choice of drug regimens. However, there are difficulties with the drug susceptibility test because these organisms behave differently in vitro than in vivo.

Treatment / Management

The treatment of NTM requires a holistic and patient-centered approach based on the quality of life and patient benefits, instead of expecting mycobacteria eradication. An NTM lung infection differs from a TB lung infection in that it does not require immediate initiation of treatment upon diagnosis. The treatment of NTM lung infection includes an interprofessional approach and a discussion of risk and benefits. The therapy should remain in place until 12 months of negative cultures have been obtained. Bimonthly sputum cultures should also get collected until 12 months of negative cultures have been achieved. During the treatment, the patient requires close monitoring for drug side effects and medication compliance and adherence.

Treating mycobacterial avium intracellularly complex (MAC) lung disease

The treatment of mycobacterial avium intracellularly complex (MAC) lung disease depends on clinical presentation, including nodular or bronchiectasis disease, cavitary diseases, and advanced (severe) or previously treated disease.

Treatment for bronchiectasis or cavitary disease

The first regimen for the treatment of bronchiectasis disease includes clarithromycin [1000 mg three times per week] or azithromycin [500 to 600 mg three times per week] together with rifampin [600 mg three times per week]. The primary treatment regimen for cavitary disease is clarithromycin [500 to 1000 mg per day] or azithromycin [500 to 600 mg three times per week] together with ethambutol [15 mg per kilogram per day] and rifampin [450–600 mg per day]. Furthermore, streptomycin or amikacin [10 mg per kilogram three times per week] can be an added therapy.

The treatment of advanced disease

The treatment of advanced (severe) or previously treated disease includes clarithromycin [500 to 1000 mg/day] or azithromycin [250 mg/day] together with rifabutin [150 to 300 mg] or rifampin [450 to 600 mg once daily], ethambutol [15 mg per kilogram], and streptomycin or amikacin [10 mg per kilogram intramuscular or intravenous three times/week; maximum dose 500 mg for age over 50 years for the first 2 to 3 months]. The addition of moxifloxacin [400 mg orally once/daily] to the previous combination regimen may improve outcomes in refractory diseases or treatment failing.

Treatment for refractory disease

Refractory pulmonary infection is a failure to achieve negative cultures for more than six months. The regimen of treatment is the administration of amikacin liposome inhalation suspension once daily at a dose of 590 mg/8.4 milliliter (one vial) with a specialized nebulizer system only, along with an optimized multi-drug background regimen.

Duration of therapy

In those achieving three consecutive monthly negative sputum cultures 12 months after last positive cultures for six months, continue for an additional 12 months. The benefit of extended therapy in those not achieving three consecutive monthly negative sputum cultures by six months remains unestablished, although it the subject of an on-going clinical trial.[5]

Treatment of Mycobacterium Kansasii lung disease

Mycobacteria kansasiis lung disease remains a relatively easy treatable pathogen among NTM lung infection diseases. Usually, the bacteria are sensitive to the tuberculosis regimen, with a high curative rate. The recommended primary regimens are: Isoniazid [300 mg], Pyridoxine [50 mg], rifampin [600 mg], and ethambutol [15 mg/kg] for 12 months of culture-negative sputum. Recently it has been demonstrated that adding to the previous treatment a macrolide such as Streptomycin during the first 2 to 3 months has high effectiveness with a low relapse rate.[6]

Treatment for Mycobacterium abscessus complex lung disease

The treatment of Mycobacterium abscessus complex (MABC) lung infection remains complicated because of the high treatment failure rate. Therefore, more clinical trials are needed to establish a successful treatment that results in the eradication and cure of the disease. In general, the primary regimen consists of a macrolide with two parenteral agents for an extended period. Also, the treatment divides between the intensive phase that uses imipenem [1000 mg IV/12 hrs] or cefoxitin [IV, 8 to 12 gm/day, divided into 2 or 3 doses], azithromycin [250 to 500 mg orally once/daily] along with amikacin [IV, 15 mg/kg/once/daily] with adjustable doses until obtaining peak serum concentration of 20 to 30 ug/ml. This proposed treatment should last 2 or 3 months, depending on the severity of infection, clinical response, tolerability, and toxicity. Finally, the continuation phase uses azithromycin [250 to 500 mg].

The role for surgery

NTM lung infection can be challenging to manage with antibiotic therapy. In these cases, adjuvant surgical therapy to remove the most severely destroyed lung can promote treatment success. In the cases of massive hemoptysis, surgery may be the best choice. Recent studies have reported successful treatment, with sputum conversion of 80 to 100% in patients after adjuvant surgical reception[7][8][9]. Surgery requires a comprehensive preoperative evaluation since recent research has shown that postoperative complications have morbidity of 7% to 25% and a mortality rate of 0% to 3%.

Medication side effects

One essential piece of information that is important to include when discussing the medication regimen with patients has to do with medication side effects, reactions, and interactions. Physicians and pharmacists must always keep in mind that patients deserve to know as much information as possible about any new treatment. In the case of treatment with NTM, the most used medications are macrolides, antituberculosis medications.

In the case of macrolides like azithromycin or erythromycin, the most common side effects are gastrointestinal symptoms, including nausea, heartburn, etc. Another side effect of this type of medication is the prolongation of QT, leading to cardiac arrhythmias. It is always essential to have a baseline EKG when using this medication. Cholestatic hepatitis has been often reported in patients using this medication. Finally, transient reversible tinnitus or deafness with over 4 gm/day of erythromycin IV has occurred in a patient with renal impairment.

Rifampin is potentially hepatotoxic. It requires caution in a patient with ongoing liver impairment or excessive use of alcohol. If elevated bilirubin and/or a substantive increase in liver-associated enzymes occurs, discontinue Rifampin therapy. One of the most known side effects with rifampin is red-orange discoloration of urine, feces, and saliva. It can stain contact lenses permanently. There are reports of thrombocytopenia and vasculitis.

Ethambutol is another medication used in the treatment of NTM. One of the most serious adverse reactions is optic neuritis with decreased visual acuity, central scotoma, loss of ability to see green, and perception problems; peripheral neuropathy and headache are the most commons side effects reported.

Differential Diagnosis

Like other lung etiologies, NTM lung infection affects the host in several ways. Clinical manifestation could mimic other lung infections, such as Mycobacterial tuberculosis, atypical bacterial infections, and chronic lung diseases. Clinicians should approach the differential diagnostic of pulmonary pathologies based on the clinical manifestations and radiological characteristics. Among the differential diagnosis infections, neoplasia, and connective tissue diseases are the most common that share similarities to NTM lung infections. Mycoplasma, chlamydia, and viral pneumonia are relevant entities to include in the differential. Others are fungal lung infections like Aspergillus, Histoplasma, and Coccidiosis, to name a few. Small cell and non-small cell lung cancer are important to consider, especially in patients with weight loss and lymphadenopathy. Moreover, disorders of the connective tissue, such as rheumatoid arthritis lung disease, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, or eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, can represent an essential part in the differential as well. Overall, any entity that presents with respiratory manifestations, and either cavitary or bronchiectasis radiological lung pictures on images is part of the differential diagnosis and needs to be ruled out.

Prognosis

The prognosis of NTM lung infection is guarded. Patients who have a fragile immune system are more prone to worse outcomes when compared with immunocompetent patients. Also, the prognosis will depend on the type of NTM lung infection. Recent studies have shown that patients with MAC lung infection have a better prognosis when compared to patients with other NTM infections.[10] Also, the mortality rate of patients with lung infection with Mycobacterial abcessus is greater when compared with patients with other NTM lung infections.[11] Finally, the main predictor of mortality in NTM lung infection seems to be chronic underlying lung diseases in combination with the type of non-tuberculosis mycobacterial lung infection, especially Mycobacterial abcessus.

Complications

Like other lung etiologies, NTM lung infection affects the host in several ways. Clinical manifestation could mimic other lung infections, such as Mycobacterial tuberculosis, atypical bacterial infections, and chronic lung diseases. Clinicians should approach the differential diagnostic of pulmonary pathologies based on the clinical manifestations and radiological characteristics. Among the differential diagnosis infections, neoplasias, and connective tissue diseases most commonly share similarities to NTM lung infections. Mycoplasma, chlamydia, and viral pneumonia are relevant entities to include in the differential. Others are fungal lung infections like Aspergillus, Histoplasma, and Coccidiosis, to name a few. Small cell and non-small-cell lung cancer are important to consider. Moreover, disorders of the connective tissue, such as rheumatoid arthritis lung diseases, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, or eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, represent an essential part of the differential as well. Overall, any entity that presents with respiratory manifestations, and either cavitary or bronchiectasis radiological lung pictures on images, is part of the differential diagnostic, and these conditions need to be ruled out.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Prevention of NTM is a rather challenging task due to its ubiquitous presence in the environment. Therefore, it is necessary to discuss with the patient about disease prevention remains problematic. Also, it is unclear how to assess whether the patient is susceptible to NTM and if it would be efficacious to educate patients in the avoidance of specific environmental sources. As an example, it is a known fact that hot showers can be a vector of transmission for the disease, but it is unclear if educating the patient on avoiding hot showers will decrease the chances of infection. There is not enough data that support a solid prevention strategy for the transmission of NTM.

In terms of treatment, the patient should be advised regarding the time-frame of the treatment, as this could be very lengthy. Patients must be educated with an organized care plan to achieve better outcomes. The plan must include medication regimens, side effects, preset appointments, and a timeframe of treatment completeness. Patients must be aware of potential complications. They also should be aware that only by taking the medication as prescribed can they achieve disease-free status, as this is only possible if they have negative sputum cultures for NTM after 12 months. It is necessary to build patient rapport and healthy relationships with the patients to obtain the best results.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The diagnosis and treatment of NTM are complex and best done with an interprofessional team. Patient-centered care is a practical approach and is the ultimate goal when treating patients. Research has demonstrated that an integrated interprofessional team is the best method for achieving excellent outcomes in inpatient care. Health professionals who look at the patient as a whole person may have more influence on the patient than if they look at him merely as a sick individual. The pharmacist should educate the patient on the importance of drug compliance, while also checking the medication record and verifying dosing and drug interactions. An infectious disease pharmacist can also go over the latest antibiogram data with the clinician to optimize antimicrobial effectiveness and prevent antibiotic resistance. Nursing can have involvement with medication administration as well as verifying compliance, looking for adverse events, and offering patient counsel, and reporting any concerns to the clinician staff.

In some cases, daily observer therapy may be necessary. The patient should be urged to quit smoking, as this may exacerbate the symptoms. The pharmacist should work in tandem with the infectious disease expert and monitor the patient for adverse effects to the medications. A holistic approach helps determine the patient necessities and strengths that could serve as an essential component of the treatment plan. Hence, the healthcare invitation to participate in patient-centered care improves outcomes, patient safety, and enhances interprofessional team performance. [Level 5]