Mantle Cell Lymphoma

- Article Author:

- David Lynch

- Article Editor:

- Utkarsh Acharya

- Updated:

- 6/7/2020 6:43:25 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Mantle Cell Lymphoma CME

- PubMed Link:

- Mantle Cell Lymphoma

Introduction

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is a rare subtype of B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs) defined by a confirmatory translocation of the CCND1 gene. The variety of morphologic variants may make this a challenging diagnosis, although most cases are uncomplicated. It typically follows an aggressive clinical course, although an indolent leukemia variant has been described.

Etiology

Mantle cell lymphoma is typically sporadic, but it may have a higher incidence in some families.

Epidemiology

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is a rare subtype of B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) with an annual incidence of one case per 200 000 people. MCL is more common in men (3 to 1), and the median age at diagnosis ranges 60 to 70 years old. Most common manifestations of MCL include extensive lymphadenopathy, and extranodal involvement is common. MCL has shared features of both indolent and aggressive NHL and is characterized by reciprocal chromosomal translocation t(11;14)(q13:q32) which leads to constitutive expression of cyclin D1, which plays a significant role in tumor cell proliferation via cell cycle dysregulation, chromosomal instability, and epigenetic regulation. Rare cases without this translocation may have a CCND2 translocation.

Pathophysiology

Pathologic exam with samples from tissue biopsy is essential for the diagnosis of MCL, which typically shows small lymphocytes with notched nuclei, small cell or blastoid variant type. Laboratory exams including CBC with differential, LDH, and beta-2 microglobulin, bone marrow biopsy, and imaging (CT or FDG-PET/CT) are recommended as the standard diagnostic workup as well. Further, Ki-67 index and mutation status of p53, ATM, and CCND1 are also considered important to select optimal treatment. In MCL patients with high Ki-67 index (greater than 30%),[1] blastoid variant, or neurologic symptoms, CSF study is also necessary to rule out CNS involvement and guide appropriate management. Also, 95% of MCL cases were shown to have GI involvement, but routine endoscopic evaluation is not necessary since it does not affect the management.

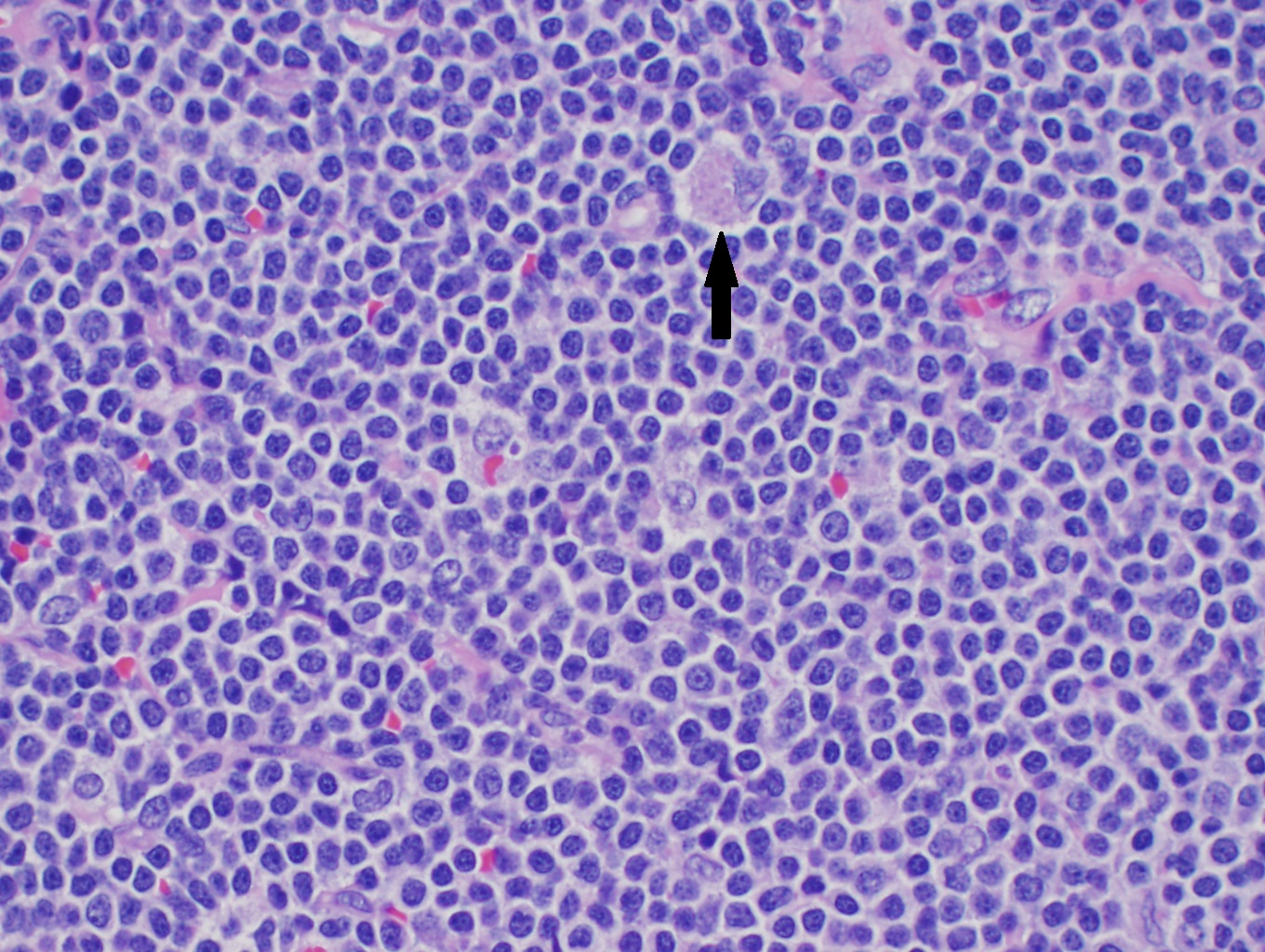

Histopathology

Although only a single translocation defines MCL, there are several morphologic variations which one must know. In lymph nodes, there is often diffuse or nodular effacement of the lymph node. MCL may also show expansion of the mantle zones with a monocytoid appearance surrounding reactive germinal centers. Often pink histiocytes may be mixed with lymphoma cells (see image).

The cytology of the cells is highly variable as well. In tissue, cells may appear small and mature with irregular nuclei, but in the blastoid variant, they may appear immature with fine chromatin mimicking acute leukemia. The pleomorphic variant shows a marked variation in nuclear size and shape. The proliferation index and mitotic are also highly variable. In blood and bone marrow aspirate smears, lymphoma cells may have discrete vacuoles which may be a clue in subtle cases.[2]

History and Physical

The disease is typically widespread at diagnosis. Symptoms and physical findings will vary based on the sites of involvement which may result in constitutional B symptoms, adenopathy related discomfort, cytopenias, cutaneous involvement, as well as gastrointestinal symptoms.

Evaluation

Immunohistochemistry plays an essential role to differentiate MCL from other NHL including follicular lymphoma (FL), diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), small lymphocytic lymphoma/chronic lymphocytic leukemia (SLL/CLL). MCL is positive for B-cell markers (CD19, CD20, CD22, CD79a). It is distinguished from other B-cell lymphomas by diffuse positivity for cyclin D1 and SOX11. Rare cases are negative for cyclin D1 but will still be positive for SOX11. MCL is typically negative for BCL6, CD10, and CD23 (while CLL is CD23 positive). Rare cases of MCL are CD10 positive.[3]

Treatment / Management

MCL remains a largely incurable disease with a median overall survival (OS) of five years. The choice of optimal treatment usually has its basis in the aggressiveness of the disease, performance status, age, and mantle cell international prognostic index (MIPI) score since there is no curative standard treatment established for MCL. Some cases with hypermutated IGH genes, SOX11 negativity, and non-complex karyotype may be monitored without immediate treatment, and delayed treatments in these particular patients group were shown to have no negative impact on OS. As such, watch and wait is appropriate in patients who have 1) Ki-67 = 30%, 2) maximum tumor diameter less than 3 cm, normal serum LDH level, 4) normal beta-2 microglobulin level, 5) no B symptoms, and 6) non-blastoid histology. In nonaggressive MCL patients, R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin, oncovin, prednisone), R-B (rituximab, bendamustine), VR-CAP (bortezomib, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, prednisone), and R-lenalidomide are considered first-line regimens. In young patients (age less than 65 years) with aggressive MCL, induction chemotherapy with R-HyperCVAD, R-CHOP/DHAP, or R-maxiCHOP followed by high-dose chemotherapy (HDC), and autologous stem cell transplantation (SCT) demonstrated survival improvement. However, in elderly patients (age = 65 years) with aggressive MCL, treatment options are limited due to comorbidities and intolerance to HDC. Rituximab combined with an intermediate dose of cytarabine and bendamustine showed some benefit, but future studies are warranted to prolong the survival in this particular subgroup. The patients with relapsed or refractory disease require more aggressive treatment, which is typically a salvage regimen followed by HDC and autologous or allogeneic SCT. Recently, ibrutinib, bortezomib, and lenalidomide received FDA approval and several other agents including Bcl-2 inhibitors and chimeric antigen receptor T-cells (CAR-T) are under clinical trials.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis primarily includes SLL/CLL and DLBCL. Both SLL/CLL and mantle cell lymphoma are CD5 positive, mature B-cell lymphomas and may be difficult to distinguish by flow cytometry alone. When there is positivity for CD200 and CD23, the diagnosis is most likely SLL/CLL. Mantle cell lymphoma is typically negative for CD23; it is positive for FMC7. Confirmation of MCL is typically performed by either FISH for t(11;14) or immunohistochemistry for cyclin D1 and/or SOX11. In tissue, uniform positive immunohistochemical expression of B-cells by Cyclin D1 and SOX 11 supports MCL. Focal positivity for Cyclin D1 may be seen in the proliferation centers of SLL/CLL and should not prompt a diagnosis of MCL.[4] Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is entertained when large cell proliferation is negative for Cyclin D1 and SOX11.

When the architecture of a lymph node is intact, and only shows focal involvement by atypical Cyclin D1 positive cells, mantle cell neoplasia is situ may be a diagnostic consideration.

Staging

Initial staging requires comprehensive scanning including a contrast CT chest/abdomen/pelvis and/or whole-body PET/CT scan along with a bone marrow biopsy with aspirate to assess the burden of disease.

Prognosis

Although International Prognostic Index (IPI) failed to show prognostic power in MCL, MCL IPI (MIPI) that incorporates age, performance status, normalized LDH level, and white blood cell (WBC) count, it was shown to discriminate MCL patients into three risk groups; low, intermediate, and high with a five-year overall survival (OS) of 60%, 35%, and 20%, respectively. Two other prognostic indexes were developed recently to accommodate the prognostic impact of Ki-67 (MIPIb) and to simplify calculation (sMIPI) although they require further clinical validation.[5] Further, CDKN2A and TP53 deletions showed inferior OS independent to Ki-67 in patients treated with autologous stem cell transplant (SCT), and TP53 overexpression was shown to correlate with worse prognosis.[6] Patients who present with involvement of the peripheral blood and bone marrow (leukemic non-nodal MCL) may follow an indolent course.[7]

Pearls and Other Issues

- Mantle cell lymphoma is a rare and a conventionally aggressive B-cell lymphoma with a heterogeneous disease profile

- Cases are typically diagnosed with diffuse Cyclin D1 positivity by immunohistochemistry or FISH for t(11;14)

- Rare cases that are negative for Cyclin D1 for t(11;14) are positive for SOX11 by immunohistochemistry

- High Ki67 proliferation index and p53 mutations are adverse prognostic findings and likely imply the need for more prompt treatment

- Chemoimmunotherapy is conventionally the choice as front line therapy among patients necessitating treatment with a potential role of cellular therapies in the salvage setting

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Mantle cell lymphoma is typically an uncomplicated diagnosis, but morphologic variants may mimic other lymphoid neoplasms. Having a low threshold for ordering additional testing for SOX11 immunohistochemistry or confirmatory FISH studies will prevent misdiagnosis. The disorder is best managed by an interprofessional team that includes a hematologist, oncologist, internist, and a radiologist.