Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

- Article Author:

- Sumina Sapkota

- Article Editor:

- Hira Shaikh

- Updated:

- 10/28/2020 12:22:13 AM

- For CME on this topic:

- Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma CME

- PubMed Link:

- Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

Introduction

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) is a neoplasm of the lymphoid tissues, which originates from B cell precursors, mature B cells, T cell precursors, and mature T cells.

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma comprises of various subtypes, each with different epidemiologies, etiologies, immunophenotypic, genetic, clinical features, and response to therapy. It can be divided into two groups, 'indolent' and 'aggressive' based on the prognosis of the disease.

The most common mature B cell neoplasms are Follicular lymphoma, Burkitt lymphoma, diffuse large B cell lymphoma, Mantle cell lymphoma, marginal zone lymphoma, primary CNS lymphoma. The most common mature T cell lymphomas are Adult T cell lymphoma, Mycosis fungoides. [1]

The treatment of NHL varies greatly, depending on tumor stage, grade, and type of lymphoma, and various patient factors (e.g., symptoms, age, performance status).

The natural history of these tumors shows significant variation. Indolent lymphomas present with waxing and waning lymphadenopathy for many years, whereas aggressive lymphomas have specific B symptoms such as weight loss, night sweats, fever and can result in deaths within a few weeks if untreated. Lymphomas that usually have indolent presentations include follicular lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma, and splenic marginal zone lymphoma. Aggressive lymphomas are diffuse large B cell lymphoma, Burkitt lymphoma, precursor B and T cell lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma, and adult T cell leukemia/lymphoma, and certain other peripheral T cell lymphomas.

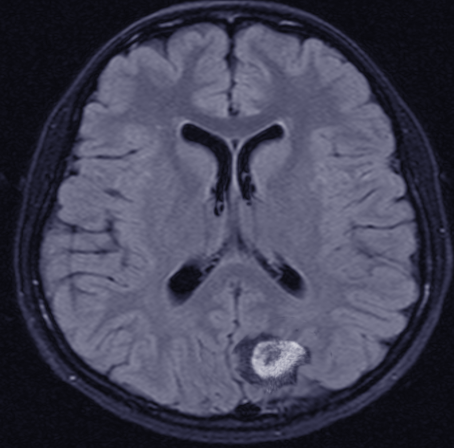

Up to two-thirds of patients present with peripheral lymphadenopathy. Rashes on the skin, increased hypersensitivity reactions to insect bites, generalized fatigue, pruritus, malaise, fever of unknown origin, ascites, and effusions are less common presenting features. Approximately half of the patients develop the extranodal disease (secondary extranodal disease) during the course of their disease, while between 10 and 35 percent of patients have primary extranodal lymphoma at diagnosis. Primary gastrointestinal (GI) tract lymphoma may present with nausea and vomiting, aversion to food, weight loss, fullness of abdomen, early satiety, visceral obstruction related symptoms. Patients may even present with features of acute perforation and gastrointestinal bleeding, and at times with features of malabsorption syndrome. Primary central nervous system (CNS) lymphoma may present with headache, features of spinal cord compression, lethargy, focal neurologic deficits, seizures, paralysis.

Etiology

Non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL) may be associated with various factors, including infections, environmental factors, immunodeficiency states, and chronic inflammation.

Various viruses have been attributed to different types of NHL.

- Epstein-Barr virus, a DNA virus, is associated with the causation of certain types of NHL, including an endemic variant of Burkitt lymphoma.

- Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) causes adult T-cell lymphoma. It induces chronic antigenic stimulation and cytokine dysregulation, resulting in uncontrolled B- or T-cell stimulation and proliferation.

- Hepatitis C virus (HCV) results in clonal B-cell expansions. Splenic marginal zone lymphoma and diffuse large B cell lymphoma are some subtypes of NHL due to the Hepatitis C virus.

- Helicobacter pylori infection is associated with increased risk of gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas, a primary gastrointestinal lymphoma.

Drugs like phenytoin, digoxin, TNF antagonist are also associated with Non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Moreover, organic chemicals, pesticides, phenoxy-herbicides, wood preservatives, dust, hair dye, solvents, chemotherapy, and radiation exposure are also associated with the development of NHL.[2][3]

Congenital immunodeficiency states associated with increased risk of NHL are Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, severe combined immunodeficiency disease (SCID), and induced immunodeficiency states like immunosuppressant medications. Patients with AIDS (Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome) can have primary CNS lymphoma.

The autoimmune disorders like sjögren syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, and Hashimoto thyroiditis are associated with an increased risk of NHL. Hashimoto's thyroiditis is associate with primary thyroid lymphomas.[4] Celiac disease is also associated with an increased risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Epidemiology

There are geographical variations in the incidence of individual subtypes, with follicular lymphoma being more common in Western countries, T cell lymphoma more common in Asia.

Overall, Non-Hodgkin lymphoma is common in age 65 to 74, the median age being 67 years.

Epstein-Barr virus-related (endemic) Burkitt lymphoma (BL) more common in Africa. The endemic variant of Burkitt lymphoma is found in equatorial Africa and New Guinea. The incidence of Burkitt Lymphoma in Africa is approximately 50-times higher than in the United States[5] The peak incidence in children is between age four to seven years, and the male: female ratio is approximately 2 to 1. The sporadic variant of Burkitt lymphoma is seen in the United States and Western Europe. BL comprises 30 percent of pediatric lymphomas and <1 percent of adult non-Hodgkin lymphomas in the United States. Sporadic BL is more common among White race individuals than in African or Asian Americans, and the majority of patients are male with a 3 or 4 to 1 male: female ratio.

Mantle Cell Lymphoma consists of about 7 percent of adult non-Hodgkin lymphomas in the United States and Europe with an incidence of approximately 4 to 8 cases per million persons per year. Incidence is shown to increase with age and appears to be increasing overall in the United States. Approximately three-quarters of patients are male, and people of the White race are affected almost twice as frequently as African Americans. The median age at diagnosis is 68 years.[6][7]

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma is the fifth most common diagnosis of pediatric cancer in children under the age of 15 years, and it accounts for approximately 7 percent of childhood cancers in the developed world. In the United States, approximately 800 new cases of pediatric NHL are diagnosed annually with an incidence of 10 to 20 cases per million people per year. High-grade lymphomas such as lymphoblastic and small non cleaved lymphomas are the most common types of NHL observed in children and young adults.

Lymphomas are rare in infants (≤1 percent) and account for approximately 4, 14, 22, and 25 percent of neoplasms in children age 1 to 4, 5 to 9, 10 to 14, and 15 to 19 years, respectively. There is a male predominance, and whites are more commonly affected than African Americans.

Pathophysiology

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma arises either from B cell, T cell, or Natural Killer cell due to chromosomal translocation or mutation/deletion. Proto-oncogenes are activated by chromosomal translocation, and tumor suppressor genes are inactivated by chromosomal deletion or mutation. The t (14;18) translocation is the most common chromosomal abnormality in Non-Hodgkin lymphoma. This translocation is most common in follicular lymphoma. The t (11;14) translocation is associated with mantle cell lymphoma. This results in the overexpression of cyclin D1, a cell cycle regulator. The t (8;14) translocation of c-myc (8) and heavy chain Ig (14) is associated with Burkitt lymphoma. Alteration in BCL-2, BCL-6, is associated with Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Primary CNS lymphoma is mostly associated with HIV/AIDS.[8]

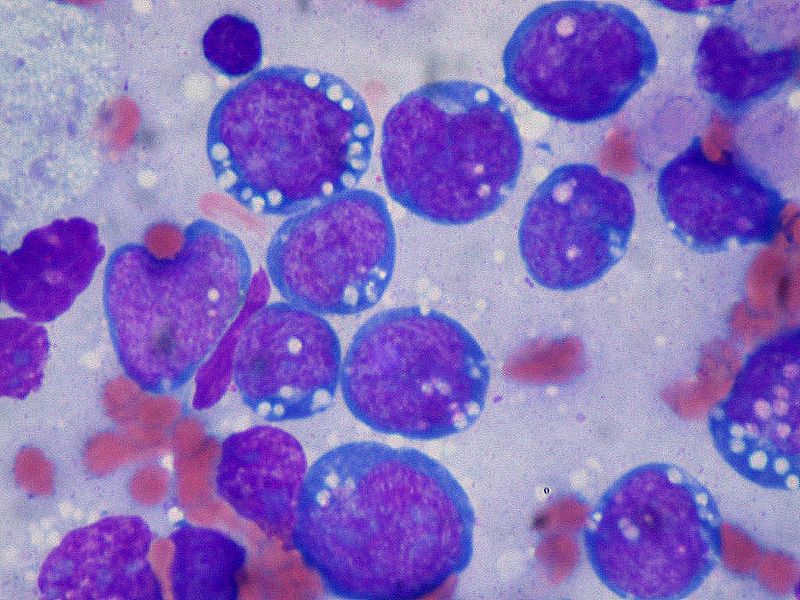

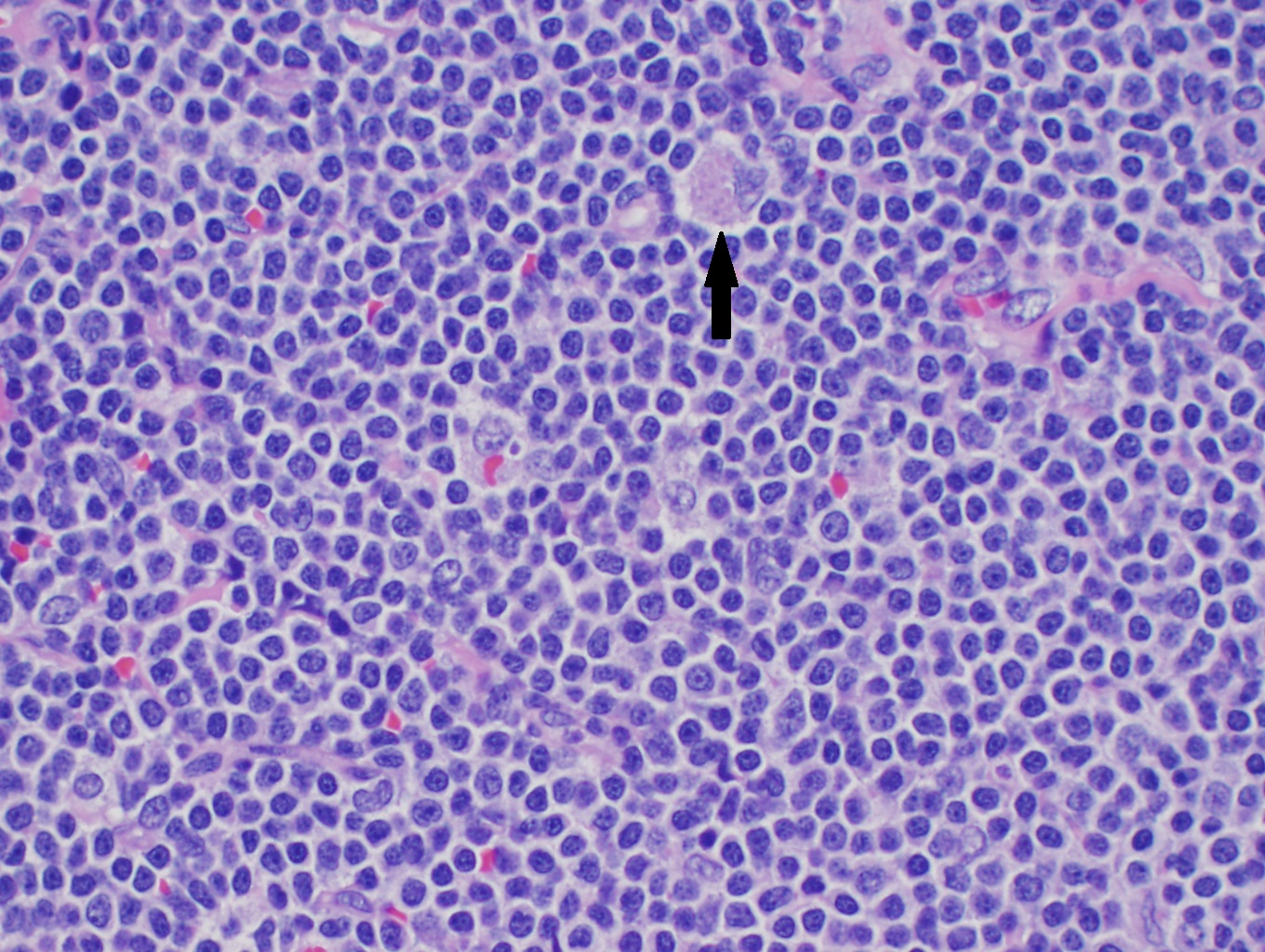

Histopathology

The common histological finding of Non-Hodgkin lymphoma includes follicular pattern and diffuse pattern. Follicular lymphoma shows a follicular pattern where uniform nodularity is seen throughout the lymph node and little variation in size and shape of follicle. The diffuse pattern shows the normal architecture of the lymph node effaced by the infiltration of small lymphocytes. In Burkitt lymphoma, the lymph node is completely effaced with a monomorphic infiltrate of lymphocytes. There are clear spaces interspersed with reactive histiocytes containing phagocytic debris.

Mantle Cell lymphoma can have a histologic pattern of diffuse, nodular, or mantle zone or can be a combination of all. Most cases are composed exclusively of small to medium-sized lymphoid cells, with slightly irregular or "notched" nuclei. On histologic review, tumor cells are usually monomorphous small to medium-sized B lymphocytes with irregular nuclei. The degree of irregularity is usually, but not always, less than that of the centrocytes found in germinal centers and follicular lymphoma.[9]

History and Physical

Patients present with complaints of fever, weight loss, or night sweats, also known as B symptoms. Systemic B symptoms are more common in patients with a high-grade variant of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. More than two-thirds of the patient presents with painless peripheral lymphadenopathy. Waxing and waning episodes of lymphadenopathy, along with other symptoms, can be seen in low-grade lymphoma. Patients have different presentations and vary according to the site involved. Clinical features of the patients according to the subtypes, are:

Burkitt Lymphoma: Patients often have rapidly increasing tumor masses. This type of lymphoma may present with tumor lysis syndrome.

Endemic (African) form may have a jaw or facial bone tumors in 50 to 60 percent of cases. The primary involvement of the abdomen is less common. The primary tumor can spread to extranodal sites like mesentery, ovary, testis, kidney, breast, and meninges.

The non-endemic (sporadic) form involves abdomen and presents most often with massive ascites, involving the distal ileum, stomach cecum and/or mesentery, bone marrow. Symptoms related to bowel obstruction or gastrointestinal bleeding, often having features of acute appendicitis or intussusception can be seen. Approximately 25 percent of cases have involvement of the jaw or facial bones. If Lymphadenopathy is present, it is usually localized. Bone marrow and CNS involvement is seen in 30 and 15 percent of cases, respectively, at the time of initial presentation, but are more common in the recurrent or treatment-resistant disease.[10] Kidney, testis, ovary, and breast can also be involved.

The patients with immunodeficiency-related Burkitt Lymphoma have presentation according to the signs or symptoms related to the underlying immunodeficiency (e.g., AIDS, congenital immunodeficiency, acquired immunodeficiency due to hematopoietic or solid organ transplantation). Immunodeficiency-related cases most often involve lymph nodes, bone marrow, and CNS.

Mantle cell Lymphoma: Most patients with mantle cell lymphoma have the advanced-stage disease at diagnosis (70 percent). Approximately 75 percent of patients initially present with lymphadenopathy, the extranodal disease is the primary presentation in the remaining 25 percent.[11] Common sites of involvement include the lymph nodes, spleen (45 to 60 percent), Waldeyer's ring, bone marrow (>60 percent), blood (13 to 77 percent), and extranodal sites, such as the gastrointestinal tract, breast, pleura, and orbit. Up to one-third of patients have systemic B symptoms, such as fever, night sweats, and unintentional weight loss, at presentation.

Gastrointestinal Lymphoma: Usually presents with nonspecific symptoms such as epigastric pain or discomfort, anorexia, weight loss, nausea and/or vomiting, occult GI bleeding, and/or early satiety.

Primary central nervous system (CNS) lymphoma: Patients with primary central nervous system (CNS) lymphoma may present with headache, lethargy, focal neurologic deficits, seizures, paralysis, spinal cord compression, or lymphomatous meningitis.

Involved lymphoid sites should be carefully examined. These include Waldeyer's ring (tonsils, the base of the tongue, nasopharynx), cervical, supraclavicular, axillary, inguinal, femoral, mesenteric, retroperitoneal nodal sites should be examined. The liver and spleen should be examined.

Head and neck examination should be done. Enlargement of preauricular nodes and tonsillar asymmetry suggests nodal and extranodal involvement of the head and neck, including Waldeyer's ring.

Orbital structures like the eyelid, extraocular muscles, lacrimal apparatus, conjunctivae can be involved in the marginal zone, mantle cell lymphoma, and primary central nervous lymphoma (Primary CNS lymphoma). Therefore, these structures should be examined.

Mediastinal involvement can be seen in primary mediastinal large B cell lymphoma or due to secondary spread. Patients with mediastinal involvement can present with a persistent cough, chest discomfort, or without any clinical symptoms, but patients usually have an abnormal chest X-ray. Superior vena cava syndrome can be part of the clinical presentation.

The involvement of retroperitoneal, mesenteric, and pelvic nodes is common in most histologic subtypes of NHL. Ascites may be present due to lymphatic obstruction, which is usually chylous.

About 50 percent of patients may develop the extranodal disease (secondary extranodal disease), while between 10 and 35 percent of patients will have primary extranodal lymphoma at the time of diagnosis.[12] The most common site of primary extranodal disease is the gastrointestinal tract, followed by skin. Other sites involved with aggressive NHLs at presentation include the testis, bone, and kidney. Rare sites include the ovary, bladder, heart, adrenal glands, salivary glands, prostate, and thyroid. Extra lymphatic disease symptoms are usually seen associated with aggressive NHL and are not common in the indolent lymphomas.

Testicular NHL is the most common malignancy involving the testis in men over age 60. It usually presents as a mass and comprises 1 percent of all NHL, and 2 percent of all extranodal lymphomas.[13]

Epidural spinal cord compression (ESCC) can cause irreversible loss of motor, sensory, and/or autonomic function. NHL is thought to first involve the paraspinal soft tissues and then invade the cord via the vertebral foramen without first causing bony destruction.[14]

Evaluation

Workup in Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma should include the following:

- Complete blood count: May show anemia, thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, pancytopenia, lymphocytosis, thrombocytosis. These changes in peripheral blood counts can be due to extensive bone marrow infiltration, hypersplenism from splenic involvement, or blood loss from gastrointestinal tract involvement.

- Serum chemistry tests: Can help rule out tumor lysis syndrome, commonly in rapidly proliferative NHL such as Burkitt or lymphoblastic lymphoma. Lactate dehydrogenase level can also be elevated due to high tumor burden, or extensive infiltration of the liver.

- Imaging: usually CT scan of neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis, or PET scan. Dedicated imaging such as MRI of the brain and spinal cord or testicular ultrasound might be needed.

- Lymph node and/or tissue biopsy: A lymph node should be considered for a biopsy if one or more of the following lymph node characteristics is present: significant enlargement, persistence for more than four to six weeks, progressive increase in size. In general, lymph nodes greater than 2.25 cm (i.e., a node with biperpendicular diameters of 1.5 x 1.5 cm) or 2 cm in a single diameter provides the best diagnostic yields. Excisional lymph node biopsy is the gold standard for the diagnosis. Fine Needle Aspiration of the lymph node is avoided. An excisional biopsy of an intact node allows sufficient tissue for histologic, immunologic, molecular biologic assessment, and classification by hematopathologists.[15][16] Specific yields of peripheral lymph nodes in patients who are subsequently proven to have NHL are as follows: supraclavicular nodes are 75 to 90 percent, cervical and axillary nodes are 60 to 70 percent, inguinal nodes are 30 to 40 percent.

- Lumbar puncture: usually reserved in those with a high risk of CNS involvement, i.e., highly aggressive NHL (Burkitt lymphoma, DLBCL, peripheral T cell lymphoma, grade 3b FL, mantle cell lymphoma, precursor T or B lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive NHL), who have epidural, bone marrow, testicular, or paranasal sinus involvement, or at least two extranodal disease sites. CSF should be sent for both cytology and flow cytometry.

- Immunophenotypic analysis of lymph node: peripheral blood, and bone marrow. The tumor cells in Burkitt lymphoma express surface immunoglobulin (Ig) of the IgM type and immunoglobulin light chains (kappa more often than lambda), B cell-associated antigens (CD19, CD20, CD22, CD79a), germinal center-associated markers (CD10 and BCL6), as well as HLA-DR and CD43Expression of CD21, the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)/C3d receptor, is dependent on EBV status of the tumors. Essentially all cases of endemic BL are EBV positive and express CD21, whereas the vast majority of non-endemic BL in non-immunosuppressed patients are EBV negative and lack CD21 expression. Mantle cell tumor cells express high levels of surface membrane immunoglobulin M (IgM) and IgD (sIgM±IgD), which is more often of lambda light chain type. They also demonstrate pan-B cell antigens (e.g., CD19, CD20), CD5, and FMC7. Nuclear staining for cyclin D1 (BCL1) is present in >90 percent of cases, including those that are CD5 negative.

- Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy: sometimes needed for the staging of the NHL. However, with the widespread use of PET scan, its utility is decreasing.

Treatment / Management

Treatment of Non-Hodgkin lymphoma is based on the type, stage, histopathological features, and symptoms. The most common treatment includes chemotherapy, radiotherapy, immunotherapy, stem cell transplant, and in rare cases, surgery. Chemoimmunotherapy, i.e., rituximab, in combination with chemotherapy, is most commonly used. Radiation is the main treatment for early-stage (I, II). Stage II with bulky disease, stage III, and IV are treated with chemotherapy along with immunotherapy, targeted therapy, and in some cases, radiation therapy. Treatment according to the type of the lymphoma are listed below:

B Cell Lymphoma

Diffuse Large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL): In Stage I or II, the R-CHOP regimen is often given for 3 to 6 cycles, with/without radiation therapy to the lymph node that is affected. In stage III or IV, six cycles of R-CHOP is the preferred treatment. Imaging tests such as PET/CT scan is done to evaluate the response of treatment after 2-4 cycles. Intrathecal chemotherapy or high doses of methotrexate intravenously is given to the patients in the presence or at high risk of central nervous system involvement. For "Double-hit" lymphomas, that is with translocations of MYC and BCL2 and/or BCL6 as detected by FISH or standard cytogenetics, DA-EPOCH-R is preferred. Refractory or relapsed DLBCL can be treated salvage regimen followed by bone marrow transplant for eligible patients, or Chimeric antigen receptor T cell (CAR-T) cell therapy.[17] CAR-T therapy is a form of immunotherapy in which the patient's own T lymphocytes are genetically modified with a gene that encodes a CAR that targets the patient's cancer. CAR-T therapy has shown effectiveness against refractory CD19-expressing B lymphoid malignancies.[18]

Follicular lymphoma: This type of lymphoma has indolent nature, and it shows a good response to treatment, but it is quite difficult to cure. Relapse is usually common after several years. Patients with low burden disease can be observed, and treatment deferred unless symptomatic. The preferred treatment in stage I and stage II in the early stage is radiotherapy. Chemotherapy, along with a monoclonal antibody, is another option. Treatment in stage III, IV, and bulky stage II lymphoma is a monoclonal antibody (rituximab or obinutuzumab) along with chemotherapy. Among the chemotherapy options, bendamustine or a combination regimen such as CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) or CVP (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone) are commonly used. After the response to initial treatment, the role of maintenance therapy is conflicting.

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL): MCL with multiple areas of involvement are commonly treated with aggressive chemotherapy plus rituximab in eligible patients. Intense chemotherapy regimens such as R-Hyper-CVAD regimen (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin (Adriamycin), and dexamethasone, alternately given with high-dose methotrexate plus cytarabine) + rituximab, alternating RCHOP/RDHAP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone)/(rituximab, dexamethasone, cytarabine, cisplatin), NORDIC regimen (dose-intensified induction immunochemotherapy with rituximab + cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, prednisone [maxi-CHOP]) alternating with rituximab + high-dose cytarabine, or RDHAP (Rituximab, dexamethasone, cytarabine, cisplatin). After the response to initial chemotherapy, high-dose therapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation is undertaken in eligible patients. This is typically followed by maintenance rituximab for three years.

Burkitt lymphoma: This is a very fast-growing lymphoma. Some examples of chemo regimens used for this lymphoma include Hyper-CVAD (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin [Adriamycin], and dexamethasone) alternating with high dose methotrexate and cytarabine (ara-C) + rituximab, CODOX-M (cyclophosphamide, vincristine [Oncovin], doxorubicin, and high-dose methotrexate) alternating with IVAC (ifosfamide, etoposide [VP-16], and cytarabine [ara-C]) + rituximab, or Dose adjusted EPOCH (etoposide, prednisone, vincristine [Oncovin], cyclophosphamide, and doxorubicin) + rituximab.[19] Intrathecal methotrexate is given when there is evidence of involvement of the brain and spinal cord. Tumor lysis syndrome is common in Burkitt lymphoma. Therefore, tumor lysis syndrome prophylaxis and monitoring are required.

Primary CNS lymphoma: High dose methotrexate based chemotherapy regimen has been shown to be the most effective treatment. If the patient achieves complete response to initial chemotherapy, high-dose therapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation should be considered for eligible patients.

T Cell Lymphoma

Anaplastic large cell lymphoma: This is rapidly growing lymphoma and mainly affects lymph nodes. Brentuximab vedotin + CHP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone) is preferred. Other regimens include CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone), or CHOEP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, etoposide, and prednisone).

Adult T cell leukemia/lymphoma: It is linked to infection with the HTLV-1 virus. There are four subtypes, and treatment varies depending on the subtype. Smoldering and chronic subtypes grow slowly. These often do not require treatment. If treatment is needed, interferon and the antiviral drug zidovudine to treat HTLV-1 infection, or skin-directed therapy if the skin is involved. The acute subtype is treated with either antiviral treatment or chemotherapy (typically the CHOP regimen). If it responds to chemotherapy, consider allogeneic stem cell transplant. Lymphoma subtype is often treated with chemotherapy; antiviral therapy is not helpful for this subtype. It may involve the brain and spinal cord, therefore intrathecal chemotherapy is given.

Enteropathy associated T cell lymphoma: This is highly associated with celiac disease. Combination chemotherapy is preferred. Patients should be evaluated for surgery at the diagnoses, prior to chemotherapy or radiation, because these patients are at high risk of perforation or intestinal blockage (obstruction). A stem cell transplant may be an option if the lymphoma responds to chemotherapy.

Other

HIV associated lymphoma: Patients with HIV tend to have more aggressive forms of lymphoma such as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, primary CNS lymphoma, or Burkitt lymphoma. The use of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) to treat HIV in addition to chemotherapy±immunotherapy is usually employed.

Some exceptions in the treatment of lymphomas can be found here:

Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma of the stomach: If infection with Helicobacter pylori is present and the lymphoma is confined to the stomach, and peri-gastric lymph nodes, treatment with antibiotics and Histaminic (H2) blockers can eliminate the organism-related antigenic stimulus, and the lymphoma may regress permanently.

Mycosis fungoides: This type of T-cell lymphoma of the skin usually has a very indolent course and is best treated with skin-directed treatments, including topical steroids, topical retinoids, skin irradiation, psoralen-associated ultraviolet exposure, topical chemotherapy. If failure with skin-directed therapies can then use systemic biologic therapies.

Differential Diagnosis

Medical conditions mimicking symptoms similar to Non-Hodgkin lymphoma are:

- Hodgkin Lymphoma

- Epstein Barr Virus infection

- Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

- Intussusception

- Appendicitis

- Toxoplasmosis

- Metastasis from the primary tumor (e.g., nasopharyngeal carcinoma, soft tissue sarcoma)

- Malignancies or lymphoproliferative disorders like granulocytic sarcoma, multicentric Castleman disease.

- Mycobacterial and other bacterial infections causing benign lymph node infiltration and reactive follicular hyperplasia.

Diseases mentioned above may have localized or generalized lymphadenopathy and should be differentiated from Non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Whenever the diagnosis is confusing and not clear, a second opinion from expert hematopathologists should be taken into consideration before treatment. Flow cytometry and cytogenetics can be done, which help in the differentiation of various conditions.

Radiation Oncology

Radiation therapy is recommended in the following situations:

- Early-stage (stage I or II): Radiation therapy is given alone or in combination with chemotherapy.

- Advanced and aggressive lymphomas: Usually, chemotherapy is the mainstay of treatment. However, radiation can be employed for palliation purposes, e.g., pain, lymphadenopathy causing urinary/gastrointestinal tract obstruction.

Radiation therapies are given for several weeks and mostly given five days a week if given for treatment. Palliative radiation is usually shorter.

Toxicity and Side Effect Management

Complications following treatment variable depending on the type of chemotherapy used and if radiation or surgery were used as adjunctive measures. Common adverse events of chemotherapy include myelosuppression, neutropenic fever, and immunosuppression. Myelosuppression is treated with transfusions (red cells and platelets) or the administration of colony-stimulating factors (e.g., granulocyte colony-stimulating factor). Neutropenia leads to increase risk of infections from bacteria, viruses, and fungi. Management is dependant on the degree of neutropenia and if febrile. Patients are also susceptible to infections like Varicella and herpes zoster. Post-exposure prophylaxis is given against varicella-zoster infection.

Multiple chemotherapeutic agents induce nausea and vomiting. Usually, anti-emetic serotonin receptor antagonists and/or benzodiazepines among other agents are used for treatment and prophylaxis.

Anthracycline can cause cardiotoxicity, especially doxorubicin. Dexrazoxane has shown significant benefits in anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity. Radiotherapy can also cause heart failure, but the mechanism is different from that of chemotherapy. It causes diffuse fibrosis in the interstitium of the myocardium and progressive fibrosis of pericardial layers, cells in the conduction system, and the cusps or leaflets of the valves. Left ventricular ejection fraction is usually preserved.

Vincristine can cause neurotoxicity.

Long-term fatigue is a common symptom present in two-thirds of survivors of NHL. Fatigue usually improves in the year after treatment completion, but a significant number of patients continue to experience fatigue for months or years after treatment.

The risk of developing a second malignancy is increased in long-term survivors of NHL. The risk of developing a second malignancy differs depending upon the subtype of NHL and the treatment received. The risk of developing the myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia is high. The risk of developing lung cancer and cutaneous melanoma was increased among survivors of follicular lymphoma. Depending on the area of radiation, patients can develop squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck and breast cancer.

Radiation to the neck and mediastinum can result in hypothyroidism. Patients undergoing hematopoietic cell transplantation with total body irradiation (TBI) conditioning were documented to suffer from the growth hormone deficiency, hypogonadism, insulin resistance, and dyslipidemia.

NHL survivors are at risk for developing endocrine abnormalities such as gonadal dysfunction and hypothyroidism. Cytotoxic agents and radiation therapy can produce gonadal dysfunction in both males and females. Fertility preservation should be offered to all. Options include freezing (cryopreservation) of embryos, oocytes, and spermatozoa.

Cranial irradiation, a history of intrathecal chemotherapy, older age at the time of treatment, and hematopoietic cell transplantation can lead to neurologic and psychiatric complications like post-traumatic stress disorder and disorder. Patients treated with an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (rituximab) are at risk for the development of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML). All patients at increased risk should undergo screening for neurocognitive impairment so that appropriate occupational therapy and social services referrals may be made.

Staging

The Lugano classification is the current staging used for patients with NHL. The Lugano classification is based on the Ann Arbor staging system, which was originally developed for Hodgkin lymphoma in 1974 and modified in 1988. This staging system is based on the number of tumor sites (nodal and extranodal) and their location.

- Stage I refer to NHL that involves a single lymph node region (stage I) or a single extra lymphatic organ or site (stage IE) without nodal involvement. A single lymph node region can involve one node or a group of adjacent nodes.

- Stage II refers to two or more involved lymph node regions on the same side of the diaphragm (stage II) or with localized involvement of an extra lymphatic organ or site (stage IIE).

- Stage III refers to lymph node involvement on both sides of the diaphragm (stage III).

- Stage IV refers to the widespread involvement of one or more extra lymphatic organs like liver, bone marrow, lung, with or without associated lymph node involvement.

The subscript "E" is used if the limited extranodal extension is noted; the more extensive extranodal disease is categorized as stage IV. Spleen involvement is considered nodal, rather than extranodal.

Prognosis

Prognosis of non-Hodgkin lymphoma mainly depends on histopathology, the extent of involvement, and patient factors. International Prognostic Index (IPI) and its variant are used as the main prognostic tools in patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma. It helps to determine overall survival after standard of care treatment. IPI is assessed by factors including age>60 years, Serum LDH more than normal, Eastern Cooperative oncology group(ECOG) performance status more than or equal to 2, clinical stage III or IV, and >1 extranodal involvement. One point is given for each of the factors, total score from (0 to 5) which determines the degree of risk. These are classified as low risk (0-1 adverse factor), Intermediate risk (2 adverse factors), and poor risk (three or more adverse factors). Congenital or acquired immunodeficiency states are associated with an increased risk of lymphoma and response to therapy is poor. [20] IPI has been modified for most of the NHL for better assessment of prognosis, e.g., FLIPI for follicular lymphoma, MIPI for mantle cell lymphoma, and so on.

Patients with aggressive T- or NK cell lymphomas usually have a worse prognosis. Patients with low-grade lymphomas have increased survival which is usually 6-10 years. However, they can have the transformation to high-grade lymphomas.

Complications

Life-threatening emergent complications of NHL should be considered during the initial workup and evaluation. Early recognition and prompt therapy are critical for these situations, which may interfere with and delay treatment of the underlying NHL. These can include:

- Febrile neutropenia

- Hyperuricemia and tumor lysis syndrome - Presents with fatigue, nausea, vomiting, decreased urination, numbness, and tingling of legs and joint pain. Laboratory findings include an increase in uric acid, potassium, creatinine, phosphate, and a decrease in calcium level. This can be prevented with vigorous hydration and allopurinol.

- Spinal cord or brain compression

- Focal compression depending on the location and type of NHL - airway obstruction (mediastinal lymphoma), intestinal obstruction and intussusception, ureteral obstruction

- Superior or inferior vena cava obstruction

- Hyperleukocytosis

- Adult T-cell leukemia-lymphoma can cause hypercalcemia

- Pericardial tamponade

- Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma with Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia can cause hyperviscosity syndrome

- Hepatic dysfunction [21]

- Venous thromboembolic disease [22]

- Autoimmune hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia - can be observed with small lymphocytic lymphoma

Deterrence and Patient Education

The patient should receive detailed information on all the available treatment options, adverse effects of chemotherapy, and their treatment options and prognosis. The patient should be informed about the oncologic emergencies that may require an emergency department visit. Patients dealing with anxiety and depression should be referred for psychosocial counseling. Lifestyle modifications, including smoking cessation, healthy diet, exercise, and no more than moderate alcohol consumption, are important for cancer survivors.[23][24] They have been shown to improve patient quality of life, risk of recurrence, and possibly mortality. Therefore, patients should be encouraged to adopt healthy habits. Long term survivors should be educated on secondary malignancies, cardiovascular complications, etc.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

During the course of treatment, NHL patients adjust working closely with a multidisciplinary team that often includes medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, mid-level practitioners, nurses, and others. Communication among the healthcare team is essential for providing excellent care to the patient. The involvement of the patient's primary care physician (PCP) continues during treatment and after the patient completes the treatment as the PCP often has a longstanding and important relationship with the patient that predates the patient's lymphoma diagnosis.

The follow-up of cancer survivors can be discussed among the primary care provider (PCP), medical oncologist, and other cancer specialists. The type of cancer and treatment exposures, comorbidities, and other factors determine decisions regarding the need for shared care, mostly oncology care or transitioning to primary care. For example, head and neck survivors would best benefit from multi-specialty and multidisciplinary follow-up care. Also, specialty care may be required for some patients. For example, rehabilitation providers may have an important role in the prevention and management of symptoms and late effects, while uplifting survivor health and well-being.

The roles and responsibilities for survivorship care should be well-described for both patients and their providers, particularly during transitions. For the patients, the transition from oncology to primary care settings can be guided by the survivorship care plan (SCP). The SCP is established by the oncology team with the completion of treatment and is meant to be shared with the patient and his or her providers, including the PCP. The survivorship care plan help patient meets the emotional, social, legal, and financial needs of the patient. It includes referrals to specialists and recommendations for a healthy lifestyle, such as changes in diet and exercises and quitting smoking.[25]

The medical oncologist usually follows the patient closely for several years after finishing therapy, and subsequently, the patient transitions back to the PCP. This transition period can be distressing with miscommunication between even the most well-meaning providers. Establishing a survivorship care plan is one way to facilitate communication and allocation of responsibility during this time period. The patient's attendance at a survivorship clinic can also aid in promoting well-coordinated care.

Psychological effects of cancer are common and include depression, anxiety, fatigue, cognitive limitations, sleep problems, sexual dysfunction, pain, and opioid dependence or use disorder. Evaluation of symptoms and management is needed. Financial implications for care must be addressed.

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)