Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Musculocutaneous Nerve

- Article Author:

- Sohil Desai

- Article Editor:

- Matthew Varacallo

- Updated:

- 8/15/2020 8:48:58 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Musculocutaneous Nerve CME

- PubMed Link:

- Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Musculocutaneous Nerve

Introduction

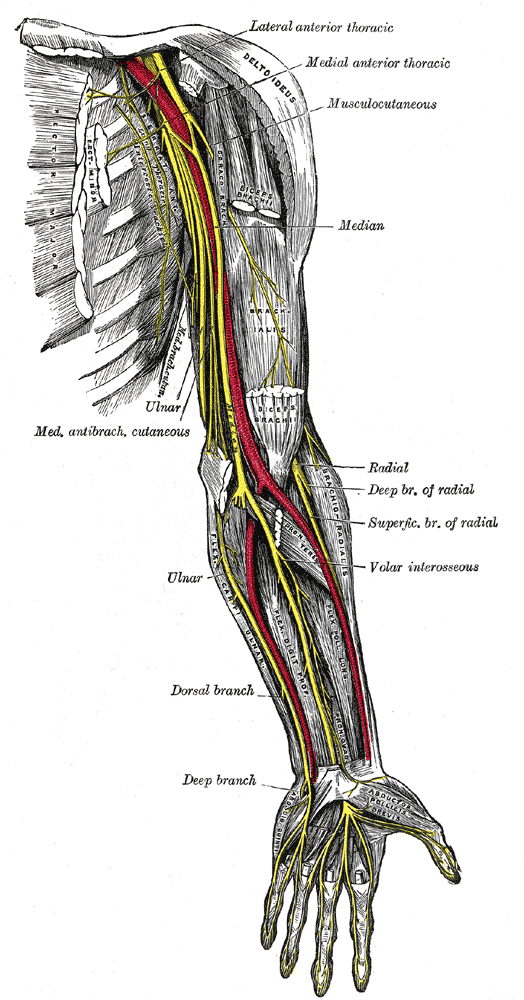

The brachial plexus is the complex set of nerves originating from the ventral roots of C5-T1 that innervates numerous muscles and cutaneous regions of the upper limb, thorax, and back. These five spinal roots form a superior, middle, and inferior trunk. Each of these trunks has an anterior and posterior division, which then continue into a medial, posterior, and lateral cord. Along the course of the brachial plexus, 18 nerves arise, including five terminal branches. The musculocutaneous nerve (roots C5-7) is a terminal branch of the lateral cord, and will be explored here in detail.

Structure and Function

The musculocutaneous nerve innervates the three muscles of the anterior compartment of the arm: the coracobrachialis, biceps brachii, and brachialis. It is also responsible for cutaneous innervation of the lateral forearm. Before further discussing the specific functions of the muscles it innervates, a description of the nerve's gross anatomy and course through the arm will be helpful.

Gross Anatomy and Course

The musculocutaneous nerve may perhaps be the most identifiable nerve of the brachial plexus. When viewing the axilla, the musculocutaneous nerve can be seen branching from the lateral cord and piercing directly into the deep surface of the coracobrachialis muscle. The nerve enters the coracobrachialis on average 5.6 cm from the muscle’s origination on the coracoid process of the scapula.[1] It then can be seen exiting the anterior surface of the coracobrachialis to continue coursing inferiorly within the anterior compartment. Throughout this portion of the arm, the nerve is found deep to the biceps brachii and superficial to the brachialis, and it gives off motor branches to these muscles along the way. Using the acromion process as the origin, the motor nerve branch points for the biceps brachii and brachialis were found to occur at an average distance of 13.0 cm and 17.5 cm along the course of the musculocutaneous nerve, respectively.[2] Having given off all of its motor fibers, the main trunk continues inferiorly. A few centimeters superior to the elbow joint, the musculocutaneous nerve then exits the space between the biceps brachii and brachialis muscles just lateral to the biceps brachii tendon and is at this point considered the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve. The lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve pierces the deep fascia superficially to gain access to the subcutaneous compartment.

This terminal cutaneous branch of the musculocutaneous nerve gives off a volar and dorsal branch to supply the skin of the lateral forearm. Cutaneous innervation of the medial forearm is supplied by the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve (roots C8-T1), a direct branch of the medial cord. The posterior forearm receives cutaneous innervation from the posterior antebrachial cutaneous nerve (roots C7-C8), a branch of the radial nerve.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Arterial Supply

The musculocutaneous nerve parallels the axillary artery proximally in the arm, but as the nerve passes into the coracobrachialis it then takes the unique course described above that does not parallel any specific artery. Nevertheless, the blood supply to the arm is managed primarily by the continuation of the axillary artery, which is termed the brachial artery once it passes the lower margin of the teres major muscle. The brachial artery and its branches- the deep brachial, radial, and ulnar arteries- supply the muscles of the arm's anterior compartment in addition to all of other structures in the arm, forearm, and hand.

Venous Drainage

Venous drainage in the arm is primarily handled by the cephalic vein and its tributaries laterally, and the basilic vein and its tributaries medially. These two veins along with the brachial vein deep in the arm all drain into the axillary vein, which carries blood back towards the right atrium. The cephalic vein closely parallels the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve distal to the nerve's passage on the lateral side of the biceps brachii tendon.

Muscles

As stated before, the musculocutaneous nerve innervates the three muscles of the arm’s anterior compartment. The coracobrachialis, the first muscle to receive innervation, originates on the coracoid process and inserts on the middle third of the medial aspect of the humerus. It flexes and adducts the shoulder at the glenohumeral joint. It is important to note that unlike the other two muscles of the anterior compartment, the coracobrachialis does not cross the elbow joint thus has no action on the elbow.

The biceps brachii muscle has a short and long head. The short head originates on the coracoid process of the scapula, while the long head originates on the supraglenoid tubercle of the scapula. These two heads come together to form a single tendon that inserts on the radial tuberosity and the fascia of the forearm via the bicipital aponeurosis. The biceps brachii acts to flex the elbow, as well as supinate the forearm. The biceps brachii muscle receives its innervation from the C5 and C6 fibers of the musculocutaneous nerve.

The brachialis muscle originates on the distal portion of the anterior humerus, and inserts on both the coronoid process and tuberosity of the ulna. Many will think of the biceps brachii when thinking of elbow flexion, but it is actually the brachialis that is considered the main flexor of the elbow. The brachialis is a versatile flexor in that it is able to flex the elbow from either a pronated or supinated forearm position.

Surgical Considerations

Surgeons always remain astute to the peripheral nerve anatomy due to relative susceptibility that many nerves have for intraoperative damage. Zlotolow, et al describe the many surgical exposures of the humerus and the specific nerves that may be injured with each approach. The deltopectoral approach, specifically for repairs of subscapularis tears, places the musculocutaneous nerve at risk. Anterolateral approaches for reduction of humeral fractures place the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve at risk.[3] Additionally, it is noted that surgeons should avoid dissecting medial to the conjoined tendon (short head of the biceps and coracobrachialis attachment on the coracoid process) due to risk of lesioning the musculocutaneous nerve.[3]

Clinical Significance

Musculocutaneous Nerve Palsy

As with all nerves, direct trauma to the musculocutaneous nerve in the form of lacerations, gunshot wounds, and nearby bone fractures has been reported.[4] While isolated musculocutaneous nerve syndromes are relatively uncommon, a few specific clinical situations have been described in the literature. Most significant is entrapment of the musculocutaneous nerve within the coracobrachialis muscle, leading to biceps brachii and brachialis weakness and atrophy with accompanying loss of sensation in the lateral forearm. It has been found that patients most apt to develop this condition are active young individuals that frequently engage in shoulder flexion and elbow flexion with the forearm in a pronated position.[5] This syndrome often occurs secondary to hypertrophy of the coracobrachialis and thus is a result of chronic overuse. It is important to note that the compressed nerve within the coracobrachialis has already given off its motor branch to the coracobrachialis, thus will not present with defects of coracobrachialis muscle function.

Another important clinical scenario is shoulder dislocation. While the most frequently injured nerve in this scenario is the axillary nerve, several cases of musculocutaneous nerve damage have been reported secondary to anterior humeral dislocations. The musculocutaneous nerve branches from the lateral cord just anterior to the glenohumeral joint, explaining its susceptibility to damage with anterior dislocations. Additionally, it has been found that downward traction and external rotation place significant tension on the nerve, and anterior humeral dislocations may place the nerve in this position.[6][7]

Lateral Antebrachial Cutaneous Nerve Palsy

In addition to the musculocutaneous nerve lesions described, specific damage to the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve has also been examined. While this sensory-only lesion often goes unnoticed clinically, there are a few clinical situations worth noting. Just prior to exiting the deep fascia to supply cutaneous innervation, the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve passes between what has been described as a tunnel created by tough fascial layers of the brachialis and bicipital aponeurosis. The nerve can be compressed by the bicipital aponeurosis in cases of chronic elbow extension with the forearm in a pronated position. [4] This can lead to hypesthesia in the lateral forearm region.

The lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve travels in close proximity to the cephalic vein, thus is at risk for injury during venipuncture procedures. General practice is to avoid the medial aspect of the cubital fossa during venipuncture due to cases of median antebrachial cutaneous nerve damage. However, cases of lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve damage similar to that described by Rayegani and Azadi suggest that caution should be taken when using the lateral aspect of the cubital fossa as well. Using as superficial an approach as possible has been suggested to reduce the overall risk of peripheral nerve damage. [8]