Embryology, Neural Tube

- Article Author:

- Ranbir Singh

- Article Editor:

- Sunil Munakomi

- Updated:

- 6/1/2020 8:25:19 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Embryology, Neural Tube CME

- PubMed Link:

- Embryology, Neural Tube

Introduction

The neural tube formation during gestational development is a complicated morphogenic process that requires various cell signaling and regulation by a variety of genes. It starts during the 3rd and 4th week of gestation. This process is called primary neurulation, and it begins with an open neural plate, then ends with the neural plate bending in specific, distinct steps.[1] These steps ultimately lead to the neural plate closing to form the neural tube. This neural tube serves as the embryonic brain and spinal cord, the central nervous system. Errors in this process can lead to congenital anomalies, such as neural tube defects.

Development

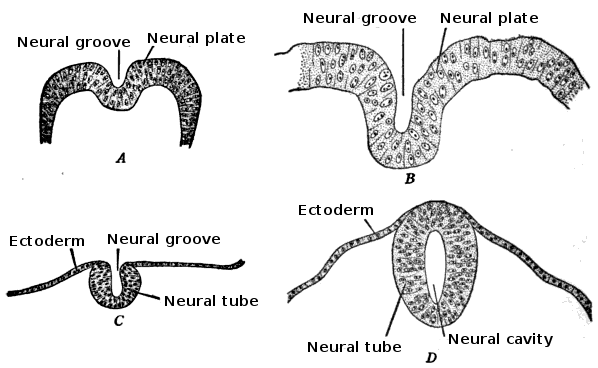

The embryo consists of three distinct layers: the ectoderm, the mesoderm, and the endoderm. The ectoderm will differentiate into the nervous system and the epidermis. The mesoderm derives from the ectoderm and gives rise to the musculoskeletal, urogenital systems, the pleura, and the peritoneal linings of the body cavity. The endoderm will form the linings of the gastrointestinal tract and airways. The notochord is also present and helps begin the process of neurulation. Later in development, the notochord will become the nucleus pulposus of the intervertebral discs. The neural plate comes from the ectoderm. By the end of week three gestation after gastrulation, the notochord induces the lateral edges of the ectoderm to begin to form the neural folds. The resulting depressed mid-region from the formation of the neural folds is called the neural groove. This whole complex of neural folds and the groove is called the neural plate and is the start of the neural plate stage. This structure divides into two regions. The upper and lower areas of the neural plate are cranial and caudal respectfully.[1]

Primary neurulation initiates at the mid-region of the neural plate and advances cranially and caudally in a zipper-like- fashion. The neural groove begins to deepen and forms a dorsolateral hinge point. The neural folds will elevate and differentiate from the non-neuronal ectoderm. The apposition stage is next as the folds will meet and fuse. The neural ectoderm and the non-neuronal ectoderm will remodel, and this results in a single closed tube that a single layer of non-neuronal ectoderm will cover. By the end of week four, the formation of the neural tube will separate from the overlying ectoderm, and its structure will be complete.[2]

Further development later in gestation will cause the cranial and caudal portions of the neural tube to form the brain and spinal cord respectfully. Some of the cells that border the neural and non-neuronal ectoderm will migrate and create layers called neural crest cells. The neural crest will develop into the peripheral nervous system, spinal, and cranial nerves.

Cellular

Neural tube formation is dependent on a variety of cellular mechanisms. Within the tissue level, neurulation begins with elongation of neuroepithelial cells in the primitive streak. The primitive streak emerges during day 15 of gestation and is involved in the gastrulation process of the embryo to form the trilaminar embryonic disc. The streak elongates rostrocaudally to form the neural plate. This elongation process of the neuroepithelial cells involves the use of paraxial microtubules, cell packing, and changes in cell-to-cell adhesion. Once the neural plate forms, it undergoes neural induction, and this process involves Hensen's node. This node is in the rostral end of the primitive streak, and its function is to induce production of the neural plate by suppressing the cellular changes that would give it an epidermal fate like the majority of the ectoderm where the neural plate derives. At this point, the neural plate is autonomous from the ectoderm and does not need the non-neural ectodermal cells to continue developing.[3]

The neural plate continues to elongate rostrocaudally and narrows mediolaterally. This process drives the intercalation of the neuroepithelial cells. Neuroepthetheilial cells during neurulation divide every 8 to -10 hours, with the priority of the daughter cells to assist in enhancing the length of the plate rather than width. The lateral ends of the plate elevate and become neural folds that start to move closer towards each other. This process yields the neural groove that becomes the lumen of the primitive neural tube. This furrowing process to form the groove and then the median hinge point requires a signal that is secreted by the sonic hedgehog protein.[3] The neuroepithelial cells and epidermal ectoderm that is immediately lateral to the neural folds drive the furrowing and folding process respectfully. The signal released from Sonic hedgehog protein induces neuroepithelial cells to wedge into hinge points. The epidermal ectoderm undergoes cell flattening, intercalation, and mitosis to induce folding.

The neural folds extend towards the dorsal midline where they meet and fuse. This fusion forms the roof of the neural tube and results in this fully separating from the overlying epidermal ectoderm, which contributes to developing the skin layer of the back of the embryo. The third layer of ectodermal cells called neural crest cells also forms during this separation process.

Secondary neurulation occurs after the formation of the neural tube. It involves the caudal part, the future lumbar, sacral, and tail levels, of the neural tube. The tail bud cells aggregate to form an epithelial cord called the medullary cord.

A critical cellular cycle is folate-mediated 1-carbon metabolism (FOCM). This mechanism involves reactions that transfer molecules called one-carbon units (1C) in the folate cycle. FOCM is essential for the biosynthesis of thymidylates, purines, and S-adenosylmethionine (SAM). This mechanism is vital for neural tube closure.

The efficiency of FOCM is dependent on the availability of tetrahydrofolate, which supplies the 1C units. Folates cannot be synthesized de novo and are required to be obtained by dietary measures.[4]

Molecular

The molecular arrangement for the edges of the neural plate to meet and fuse have multiple genes and proteins that facilitate proper apposition. Major ones are in this section:

Cilia

These are hair-like structures that help to regulate signal transduction with the use of mechanical molecular cues. Cilia are essential in major signaling pathways such as the sonic hedgehog pathway during neural tube formation. Approximately 5% of neural tube disorders have a relation to genes that are responsible for cilia formation and function.[5]

Planar Cell Polarity Pathway (PCP)

PCP, or noncanonical WNT pathways, is a complex of core proteins. These involve VANGL1/2, DISHEVELLED, CELSR1, and SCRIBBLE, and also PCP effector proteins, including FUZZY and INTURNED. These proteins are necessary for driving critical cell movements during neural tube closure. They assist in lengthening the embryo throughout the rostral-caudal axis and help narrow the neural plate. Interruptions in any of these pathways will result in a widen neural plate and will prevent the folds from joining. The most severe consequence of this can lead to a neural tube defect called cranioschisis. Cranioschisis is when the neural tube remains open from the brain down to the spinal cord.[2]

Mechanism

Neural tube formation is a complex interplay between convergence, apical constriction, and nuclear migration mediated through the Wnt pathway via the BMP signaling mechanism.[1]

Primary neurulation is a complex process of formation of the neural tube from the neural plate and eventually undergoing neuro-epithelialization. Secondary neurulation wherein tail bud from primitive streak condense, cavitates, and fuse to the central canal of neural tube followed by retrogressive differentiation and regression of caudal cell mass forming ventriculus terminale and filum terminale. Cells on edges of neural plate migrate as neural crest cells to ganglion and dorsal root as well as melanocytes and cartilage mediated by BMP signals.

Testing

Prenatal 'triple screen' maternal blood test looking for an elevated level of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) and estriol and testing the amniotic fluid for a high level of AFP, acetylcholinesterase, as well as chromosomal abnormalities, are used for screening and detecting neural tube defects.[6][7]

A prenatal anomaly scan also helps in the detection of all types of neural tube defects.

Pathophysiology

The commonly encountered neural tube defects categorized according to their embryological timeframe are as follows[8][9][8]:

- Defects of neural folding and neuropore closure—myelomeningocele, anencephaly, encephalocele

- Incomplete dysjunction—dermal sinus, dermoids, and epidermoids

- Premature dysjunction—cord lipomas

- Defective gastrulation—split cord malformation, neurenteric cysts

- Disordered secondary neurulation—thickened filum terminale, myelocystocele

- Failure of caudal neuraxial development—sacral agenesis

Clinical Significance

Neural tube defects are intense birth anomalies that can occur 21 to 28 days after conception. It is when the neural folds fail to fuse at the midline to form the neural tube.[8] Failure of the neural folds to apposition results in the abnormal development of the mesoderm, and this is responsible for developing the skeletal and muscular structures that cover the underlying neurologic structures. They occur in 2 per 1000 pregnancies worldwide and are a significant cause of stillbirth and lifelong handicaps.[10]

An essential type of neural tube defect is called cranial dysraphism. This anomaly is the failure of cranial neural tube closure and includes anencephaly and encephaloceles. Spinal dysraphism is another type of error that is due to the failure of closure of the caudal neuropore and includes spina bifida cystica and occulta. Neural tube defects classify into ventral, dorsal, or midline defects. These defects can further be classified as open where the open neural tube can be exposed to the surrounding environment, or closed where the overlying skin covers the defect. Craniorachischisis is a rare form of neural tube defect in which the neural tube fails to close throughout the entire body axis.[11]

Surgical correction is the initial treatment in utero or soon after birth with the majority of these surgical patients requiring a ventriculoperitoneal shunt by 12 months of age. Infants with spina bifida even after surgery are still at an elevated risk for nervous system malformations such as skull malformations that press the brain downward toward the spinal canal, and hydrocephalus. Other neurological defects that can occur include lower extremity weakness and paralysis, sensory loss, and bowel and bladder dysfunction. Thus, surgical treatment only provides a partial solution to neural tube defects.[12]

One etiology that can lead to severe defects is decreased folic acid uptake during pregnancy. As mentioned in previous sections, folic acid is essential in neural tube closure because it is a vital component in DNA methylation. DNA methylation is part of the epigenetic code, which regulates gene expression of the PCP pathway.[13]

The reader is encouraged to seek supplemental resources for neural tube defects as the primary objective of this article is to discuss the embryological formation of the neural tube.

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)