Odontoid Fractures

- Article Author:

- Steven Tenny

- Article Editor:

- Matthew Varacallo

- Updated:

- 7/21/2020 10:51:37 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Odontoid Fractures CME

- PubMed Link:

- Odontoid Fractures

Introduction

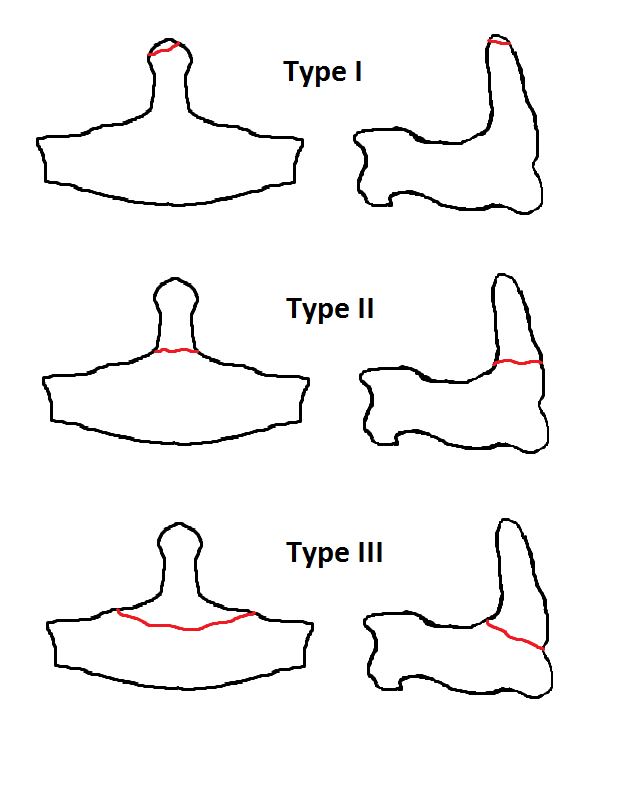

The odontoid process, or dens, is a superior projecting bony element from the second cervical vertebrae (C2, or the axis). The first cervical vertebrae (atlas) rotates around the odontoid process to provide the largest single component of lateral rotation of the cervical spine. Fracture of the odontoid process is classified into one of three types, which are type I, type II, or type III fractures, depending on the location and morphology of the fracture.[1]

Etiology

Odontoid fractures occur as a result of trauma to the cervical spine. In younger patients, they are typically the result of high-energy trauma, which occurs as a result of a motor vehicle or diving accidents. In the elderly population, the trauma can occur after lower energy impacts such as falls from a standing position. The most common mechanism of injury is a hyperextension of the cervical spine, pushing the head and C1 vertebrae backward. If the energy mechanism and resulting force are high enough (or the patient's bone density is compromised secondary to osteopenia/osteoporosis), the odontoid will fracture with varying displacement and degrees of comminution.

The odontoid fracture can also occur with hyperflexion of the cervical spine. The transverse ligament runs dorsal to (behind) the odontoid process and attaches to the lateral mass of C1 on either side. If the cervical spine is excessively flexed, then the transverse ligament can transmit the excessive anterior forces to the odontoid process and cause an odontoid fracture.[1]

Epidemiology

Fractures of the second cervical vertebrae (C2) are the most common cervical spine injuries in the elderly population. The most common type of C2 fracture is a fracture to its odontoid process (or dens). Odontoid fractures demonstrate a biphasic distribution with peak incidence rates reported in younger patients (ages 20 to 30 years) secondary to high energy mechanisms (i.e., motor vehicle accident), followed by elderly patient populations (ages 70 to 80 years) secondary to compromised bone density and low energy impact falls.

Odontoid fractures account for 10% to 15% of all cervical spine fractures. Of the types of odontoid fractures, type II is the most common and accounts for over 50% of all odontoid fractures. Type III odontoid fractures make up most of the remaining percentage of odontoid fractures. Type I odontoid fractures are rare.[1]

Pathophysiology

Type I Odontoid Fracture

A type I odontoid fracture occurs when the rostral tip of the odontoid process is avulsed (broken or torn off). This injury commonly occurs due to pulling forces from the apical ligament attachment to the odontoid process. The apical ligament attaches the tip of the odontoid process to the foramen magnum (skull base).

Type II Odontoid Fracture

A type II odontoid fracture is a fracture through the base of the odontoid process. This injury occurs most typically when there is an excessive extension of the cervical spine, and the anterior arch of C1 pushes dorsally (backward) with sufficient force on the odontoid process (dens) to fracture the odontoid process at its base. Type II odontoid fractures can also occur with hyperflexion of the neck and the transverse ligament, pushing the odontoid process forward to the point of fracture.

Type III Odontoid Fracture

A type III odontoid fracture is a fracture through the body of the C2 vertebrae and may involve a variable portion of the C1 and C2 facets. Type III odontoid fractures occur secondary to hyperextension or hyperflexion of the cervical spine in a similar manner to type II odontoid fractures. The difference is where the fracture line occurs.

History and Physical

Younger patients with an odontoid fracture typically have identifiable recent trauma (motor vehicle accident, sports-related impact, diving accident, fall from a height or downstairs). Older patients tend to have less resilient bones and can sustain an odontoid fracture after minor trauma, including fall from ground level or running into a door or cabinet. However, older individuals can also sustain an odontoid fracture from recent injuries similar to those of younger people.

On physical exam, patients may note cervical neck pain, which is worse with motion. They can also have dysphagia due to a retropharyngeal hematoma or associated parapharyngeal swelling. Less commonly, the patient may have myelopathic spinal cord injuries such as paresthesias in the arms and/or legs, weakness of the arms and/or legs, or other neurologic dysfunctions. There are fewer spinal cord injuries in odontoid fractures due to the relatively large cross-sectional diameter of the spinal canal at the level of the odontoid process compared to the diameter of the spinal cord.

Evaluation

In hospitals and countries without readily available advanced imaging capabilities, radiographs are critical to evaluate and assist in ruling out potential odontoid fractures. Recommended views include:[1]

- AP C-spine

- Lateral C-spine

- Open-mouth odontoid view

Although radiographs yield lower sensitivity and specificity rates when compared to computed tomogram (CT) scans, experienced clinicians and practitioners can still appreciate suspected injury without CT utilization. In addition, in the setting of suspected occipitocervical instability (useful in type I odontoid fractures or the setting of os odontoideum), flexion-extension radiographs should be obtained.

Advanced Imaging modalities

The imaging modality of choice is a CT of the cervical spine. The CT provides the best resolution of the bony elements allowing for identification and characterization of an odontoid fracture. If there is neurologic injury (paresthesia, weakness), then magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) without contrast of the cervical spine should be obtained to assess the cervical cord for injuries.

Some surgeons also order a CT angiogram of the cervical spine if posterior instrumentation is planned. The CT angiogram allows for better identification of the course of the vertebral arteries for surgical planning of posterior instrumentation.

Treatment / Management

The treatment of an odontoid fracture depends on the type of fracture and age of the patient.[1][2][3][4]

Type I Odontoid Fracture

Most consider a type I odontoid fracture a stable fracture and treat for six to 12 weeks in a rigid cervical orthosis (hard cervical collar). Some have suggested that rarely a type I odontoid fracture may be unstable secondary to more extensive and unrecognized ligamentous injury, and flexion/extension x-rays should be obtained at the time of removal of the cervical collar after six to 12 weeks to ensure cervical stability.

Type II Odontoid Fracture[5]

Type II odontoid fractures are inherently unstable and have a lower union rate than type III odontoid fractures due to the lower surface area of fractured bone in type II versus type III odontoid fractures. The configuration of type II odontoid fracture and age of patient also play important roles in treatment decisions. The current treatment options for a type II odontoid fracture include rigid cervical orthosis, halo vest immobilization, odontoid screw, transoral odontoidectomy, and posterior instrumentation.

Rigid Cervical Orthosis

A type II odontoid fracture is inherently unstable, and a rigid cervical orthosis is not the ideal treatment for such an injury. In the elderly population, many are not surgical candidates (due to comorbidities or poor bone quality), and the elderly typically poorly tolerate a halo vest immobilization. In such situations, a practitioner may attempt a rigid cervical orthosis, although union rates are low. Some authors have argued that a fibrous union will form with the use of a rigid cervical orthosis with time, and this may provide sufficient stability in the elderly population while avoiding the morbidity of surgery or halo vest immobilization. Note that many elderly patients also poorly tolerate rigid cervical orthosis because of pressure ulcers from the cervical collar and difficulties in eating. In some situations, the patient and/or family may elect to forego all treatment while understanding the unstable nature of the spine and risk of progressive deformity and/or cervical cord injury.

Halo Vest Immobilization

If a patient is relatively young and healthy, and there is low risk for nonunion, then halo vest immobilization may be the best treatment for a type II odontoid fracture. Risk factors for nonunion include a fractured space greater than a few millimeters between the odontoid process and vertebral body, poor alignment of the odontoid process with respect to the vertebral body, and poor bone quality and/or health status of the patient. Elderly patients poorly tolerate halo vest immobilization and have increased the risk of death with halo-vest immobilization. Younger patients typically spend six to 12 weeks in halo vest immobilization with frequent x-rays to check alignment and healing.

Odontoid Screw

An anterior odontoid osteosynthesis (odontoid screw) is a screw placed from the inferior anterior aspect of the C2 vertebral body, in a superior trajectory, and capturing the odontoid process and affixing it in place to allow bony fusion to occur. The odontoid screw has an advantage of relative preservation of motion of the upper cervical spine while treating a type II odontoid fracture. A surgeon can only place the odontoid screw if there are acceptable alignment and minimal displacement of the odontoid process, the fracture line is oblique or perpendicular to the screw trajectory, the injury is relatively recent, and the patient has acceptable body habitus to place the odontoid screw. Due to the relatively vertical orientation of an odontoid screw, a person with a short neck or large chest or sternum may not allow the surgeon an adequate trajectory for placement of the odontoid screw. Odontoid screws have a lower union rate and a higher failure rate than posterior instrumentation.

Transoral Odontoidectomy

In some situations, the odontoid process (dens) may be severely posteriorly displaced and compressing the spinal cord causing neurologic deficits. It is difficult and dangerous to reduce the odontoid process in a closed manner, so surgical removal of the odontoid process is required to relieve the compression of the spinal cord. This relief is commonly achieved through a transoral odontoidectomy, as the odontoid process commonly is located posterior to the oropharynx. If the odontoid process is removed, the cervical spine remains unstable, and the patient requires instrumented fusion, commonly from a posterior or combined anterior-posterior approach.

Posterior Instrumentation

If the patient has certain risk factors for nonunion, then posterior instrumentation may provide the best treatment option for a type II odontoid fracture. The risk factors include:

- More than a few millimeters gap between the odontoid process and vertebral body

- Poor odontoid process alignment

- Poor bone quality, older fractures

- Older patients

- Failure of other treatment modalities

- Smoking

Posterior instrumented fusion techniques vary widely and include fusion limited to C1 and C2 as well as more extensive fusions. Fusion of only C1 and C2 will lead to approximately 50% reduction of the lateral rotation of the cervical spine. Advantages of posterior fusion include a higher rate of union and stabilization than other treatment options, less risk of swallowing or vocal cord issues than an anterior approach, and avoidance of rigid cervical orthosis or halo immobilization. The major disadvantages of posterior fusion include loss of cervical spine motion and risk of damage to the vertebral arteries, exiting nerve roots or spinal cord.

Differential Diagnosis

- Anterior cervical wedge fracture

- Atlanto occipital dissociation

- Cervical burst fracture

- Cervical facet dislocation

- Cervical spinous process fracture

- Extension cervical teardrop fracture

- Flexion cervical teardrop fracture

- Hangman's fracture

- Isolated transverse process fractures

- Jefferson fracture

Pearls and Other Issues

Some entities can be mistaken for an odontoid fracture. It is important to recognize these to avoid unnecessary interventions.

Os odontoideum

Os odontoideum is a recognized anatomical variant of the normal C2 odontoid process. During the development, there are multiple ossification centers in the spine, with one being in the odontoid process, one in the odontoid tip, and one in the vertebral body. If the ossification centers in the odontoid process and vertebral body fail to fuse, then the odontoid process (dens) can appear to be detached from the vertebral body and mimic a type II odontoid fracture. In younger children, complete ossification of the spine has not yet occurred, and the normal growth pattern and ossification can also mimic a type II odontoid fracture.

Persistent Ossiculum Terminale

The rostral tip of the odontoid process has a separate ossification center during development from the remaining odontoid process. When the two ossification centers fail to fuse, there can be a persistent gap between the odontoid process and the tip of the odontoid process, which can mimic a type I odontoid fracture.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Odontoid fractures most often occur as a result of trauma to the cervical spine. Patients are often younger. The clinicians must work together in a coordinated approach to care that minimizes the risk of further injury. Trauma nurses are responsible for cervical spine immobilization. Radiologists review x-rays and scans. Neurosurgeons and orthopedists provide definitive care. Physiatrists and rehabilitation nurses coordinate care and feedback to the interprofessional team. Often pharmacist assists the team in helping to maintain pain control in the acutely injured patient. [Level 5]