Oral Melanoma

- Article Author:

- Patrick Zito

- Article Editor:

- Thomas Mazzoni

- Updated:

- 9/29/2020 4:17:58 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Oral Melanoma CME

- PubMed Link:

- Oral Melanoma

Introduction

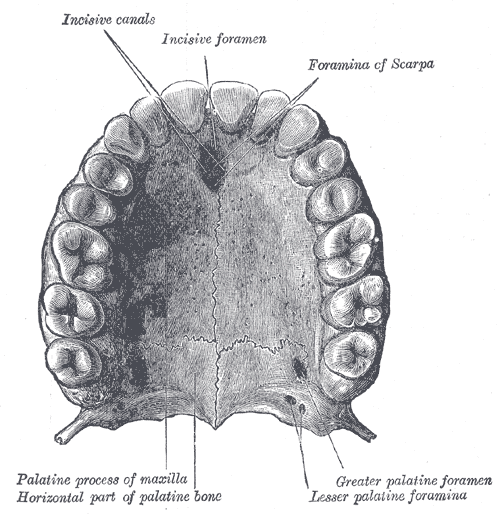

Melanocytes arise from neural crest cells and are frequently found in the skin. However, melanocytes are also found in mucosal membranes. Melanocytes in mucosal membranes are distributed to the oral cavity, nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses, esophagus, larynx, vagina, cervix, rectum, and anus. Melanoma results from a malignant change of melanocytes. Melanoma in the head and neck account for upward of 25% of all melanomas. Mucosal melanomas account for less than 1% of all melanoma. However, mucosal melanoma accounts for roughly 10% of melanoma of the head and neck. The most common sites for mucosal melanoma in order are nasal, paranasal sinuses, oral cavity, and nasopharynx. Of all mucosal melanomas, paranasal sinus has the worst prognosis. The best prognosis locations are the nasal and oral cavity. In 1885, the first case of oral melanoma was reported. Approximately 80% of oral malignant melanomas develop in the mucosa of the upper jaws (maxillary anterior gingiva). The majority of these lesions occur in the keratinizing mucosa of the palate and alveolar gingivae. Lesions are frequently asymptomatic until ulceration and hemorrhage are present. Compared with other melanomas, mucosal melanomas have the lowest percentage of 5-year survival. There is a poor 5-year survival at approximately 15% to 30% likely due to delayed detection.[1][2][3][4]

Etiology

Etiology is mostly unclear in malignant melanoma of the mouth. Mucosal melanoma of the mouth is not related to sun exposure. Risk factors largely remain obscure. Denture irritation, alcohol, and cigarette smoking have been listed as possible risk factors, but a direct relation is not substantiated.

Epidemiology

The peak age for diagnosis of mucosal melanoma is between 65 and 79 years, which is 1 to 2 decades later than cutaneous melanoma. Mucosal melanomas are found more so in women than in men. However, in oral malignant melanoma, the gender distribution is reported as 1:1. Melanoma of the lip has a slightly male predominance. Malignant melanoma of the mouth has a higher prevalence in blacks, Japanese, and Indians of Asia. The higher prevalence may be due to the higher published reports than actual rates.

Pathophysiology

Melanoma develops from a malignant transformation of melanocytes. A number of pathways have been identified.

Mutations in c-KIT

Recent data indicates that c-KIT (CD117) is overexpressed in upward of 80% of mucosal melanoma cases. This pathway is important and common in acral and mucosal melanoma, melanomas unrelated to sun exposure. KIT is a transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptor that is expressed on hematopoietic progenitor cells, melanocytes, mast cells, primordial germ cells, and interstitial cells of Cajal. Activating mutations and amplifications cause activation of growth and proliferation pathways. New drugs, such as imatinib, work on this pathway.

Mutations in BRAF

Bioinformatics Resources and Applications Facility (BRAF) protein mutations are uncommon in mucosal melanoma and found at less than 10% of cases. However, in cutaneous melanoma, BRAF mutations are found in up to 80% of melanomas.

Histopathology

The mucosa of the mouth differs from the skin. Due to the lack of histological landmarks that are analogous to the papillary, reticular dermis, and muscle bundles, a pathological leveling system and description cannot be applied properly for mucosal melanomas. Therefore, the use of Clark’s levels, which are commonly used in cutaneous melanoma, are unable to be used. Many melanomas in the mouth have a histologic similarity with lentigo maligna melanoma in a radial growth phase.

The mucosal melanomas can show 2 principal patterns: an in situ pattern and an invasive pattern. Approximately 15% of cases of oral melanoma are in situ mucosal lesions, 30% of cases are invasive lesions, and 55% of cases have a combined pattern of invasive with in situ components. Most advanced lesions have a combination pattern of invasive melanoma with an in situ component.

Melanocytic Markers

S100

- A common marker for neural tissue; acidic protein in the nucleus and cytoplasm

- Used in the workup for desmoplastic melanoma

MART-1 (MELAN-A)

- Most sensitive melanocytic marker

- Can stain pseudonests in lichenoid actinic keratosis in sun-damaged skin

- Note that in desmoplastic melanoma, MART-1 is usually negative and S100 must be performed.

MITF-1

- Nuclear stain, positive in melanocytes, mast cells, and osteoclasts

HMB-45

- Recognizes melanosomal glycoprotein gp100

- Blue nevi stain with HMB-45

History and Physical

The initial presentation of malignant melanoma of the mouth is often swelling which is usually with a brown, dark blue, or black macule. Satellite foci may surround the primary lesion. Just like cutaneous melanomas, melanoma in the mouth may be asymmetric with irregular borders. In amelanotic melanomas, pigmentation is not present. Amelanotic melanomas may simulate pyogenic granulomas. Many times, due to late diagnosis, erythema and ulceration may be present.

Evaluation

Oral melanomas are often silent with minimal symptoms until the advanced stage. On physical examination, the lesions can appear as pigmented dark brown to blue-black lesions, or apigmented mucosa-colored or white lesions. Erythema may be present if inflammation is present. The majority of the cases involve the palate and maxillary gingiva. Metastatic melanoma usually arises from the buccal mucosa, tongue, or the mandible. If an elevated lesion with a variation of color within the lesion is present, with surrounding satellite lesions and ulceration, a high grade advanced disease can be expected. Regional metastasis is rare.

Treatment / Management

Surgery is the mainstay of treatment in oral malignant melanoma. Radical excision with disease-free margins is the first goal in surgical management. A diagnostic excisional biopsy followed by wide local excision where the diagnosis is proven. Following complete surgical excision, relapse rates have been reported to be 10% to 20%.[5][6][7][8]

Neck Dissection

In a clinically positive neck, a neck dissection is mandatory in all cases of head and neck mucosal melanoma that is amenable to radical treatment.

Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy/Lymphoscintigraphy

It has less value in staging and is less useful in predicting lymphatic drainage patterns in oral melanoma.

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy is used to control local disease. This is in contrast to cutaneous melanoma. Radiotherapy is valuable in the goal of achieving relapse-free survival.

Medical Therapy

Due to the low incidence of oral melanoma, well-controlled trials with large participants have been limited. Chemotherapy and immunotherapy may have a role in the prevention of metastatic disease.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of oral melanoma involves anything that can cause pigmentation within the mouth:

- Oral melanotic macule

- Amalgam tattoo

- Labial lentigines

- Physiologic pigmentation

- Smoking associated melanosis

- Postinflammatory pigmentation

- Melanotic nevi of the oral mucosa

- Blue nevi

- Melanoacanthoma

- Melanoplakia

- Medication-induced melanosis (examples: minocycline and antimalarial drugs)

- Peutz-Jeghers syndrome

- Cushing syndrome

- Addison’s disease

- Kaposi sarcoma

- Malignant melanoma

- Amelanotic melanoma

Staging

Tumor, T

There is no T1 or T2 in mucosal melanoma.

- T3: Tumors limited to the mucosa and immediately underlying soft tissue, regardless of thickness or greatest dimension; for example, polypoid nasal disease, pigmented or non-pigmented lesions of the oral cavity, pharynx, or larynx

- T4: Moderately advanced or very advanced

- T4a: Moderately advanced disease. Tumor involving deep soft tissue, cartilage, bone, or overlying skin

- T4b: Very advanced disease. Tumor involving the brain, dura, skull base, lower cranial nerves (IX, X, XI, XII), masticator space, carotid artery, prevertebral space, or mediastinal structures

Lymph Nodes, N

- NX: Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed

- N0: No regional lymph node metastases

- N1: Regional lymph node metastases present

Distant Metastases, M

- M0: No distance metastasis

- M1: Distant metastasis

Prognosis

Overall, the prognosis of malignant melanoma is poor with 5-year survival at most 30% often due to late diagnosis.

Independent prognostic factors that have been suggested are:

- Tumor thickness greater than 5 mm

- Ulceration

- Greater than 10 mitotic figures per high power fields

Complications

After complete surgical excision, relapse rates have been reported to be 10% to 20%. Recurrence has been noted even up to 11 years following surgery.

Metastases to the lymph nodes of the neck, lungs, liver, and brain can be seen.

Consultations

Melanoma care and treatment requires a multidisciplinary approach. Melanomas of the head and neck, specifically the mouth, have a poor prognosis and often have advanced disease. Consultations with otolaryngology (head and neck surgery), surgical oncology, pathology, speech therapy, and other specialists depending on complications and distant metastases are warranted.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Preventive strategies for oral malignant melanoma are not known. Some experts suggest educating patients on regular oral self-examination and to help identify early suspicious lesions. Due to the risk of recurrence, patients with a history of oral melanoma require lifelong follow-up.

Pearls and Other Issues

Primary mucosal melanomas are aggressive tumors that are rarer than cutaneous melanoma. Head and neck mucosal melanomas are the most common. Wide excision is the treatment of choice. Oral melanoma complicated in that detection does not usually occur until the lesion is advanced. Overall 5-year survival is low which highlights the need for aggressive treatment and continued follow-up afterward. Detection of c-KIT mutations has been identified in upwards of 80% of mucosal melanomas and as little as 10% of BRAF mutations; this is the opposite of cutaneous melanoma. Newer drugs such as imatinib are used in c-KIT pathway melanomas. It is important to maintain a high index of suspicion with pigmented lesions within the oral cavity, especially those in sites most common to oral melanoma (palate and maxillary gingiva).

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

In general, primary mucosal melanomas are aggressive tumors that are rarer than cutaneous melanoma. Oral melanoma is complicated in that detection does not usually occur until the lesion is advanced. The clinicians need to maintain a high index of suspicion with pigmented lesions within the oral cavity, especially those in sites most common to oral melanoma. A self-examination strategy needs to implemented for early detection, which requires trained primary care nurses to educate the patient on proper oral examination. They also need to educate the patient on what constitutes a high-risk lesion and to communicate these findings to the clinician as soon as they arise. Despite the low incidence of the disease, a collaborative interprofessional team can help reduce morbidity and mortality associated with this disease. (Level V)