Ornithine Transcarbamylase Deficiency

- Article Author:

- Kathleen Donovan

- Article Editor:

- Nilmarie Guzman

- Updated:

- 8/24/2020 10:50:33 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Ornithine Transcarbamylase Deficiency CME

- PubMed Link:

- Ornithine Transcarbamylase Deficiency

Introduction

Ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency (OTCD) is an X-linked genetic disorder that prevents the breakdown and excretion of ammonia; this allows ammonia to rise to toxic levels and affect the central nervous system. The organ most involved in the processing of ammonia is the liver. Liver mitochondria are the primary site of the urea cycle.[1] The urea cycle converts ammonia into urea, which is water soluble and readily excreted in the urine.[2]

Etiology

The underlying cause of OTC deficiency is a gene mutation on the X chromosome. Over 100 mutations have been found to result in OTCD.[3] Patients inherit one of these mutations, or a mutation occurs de novo in his/her genome. Females more commonly have a variable age of onset because they have one normal X chromosome. Females are heterozygous for an OTCD gene mutation, leading to a reduced amount of OTC enzyme. Possible triggers for the onset of OTCD in heterozygous females include certain drugs and high catabolic states such as during infections, after trauma or after surgery. By contrast, males are hemizygous (not homozygous) for an OTCD gene mutation, because they have only one X chromosome. Males are more commonly affected as neonates or children, and generally at younger ages than females.[4] Male patients lack the OTC enzyme which leads to more severe disease than seen in females.[5]

Epidemiology

Ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency is the most common of the urea cycle disorders.[5] Urea cycle disorders occur in 1 of 8200 US live births,[6] making these disorders more common in the US than globally.[7] OTC deficiency occurs more commonly in neonates and early childhood than in adulthood.[2] Males more commonly experience severe symptoms as neonates since the mutation is on the X chromosome. Approximately 10 percent of female carriers become symptomatic.[1]

Pathophysiology

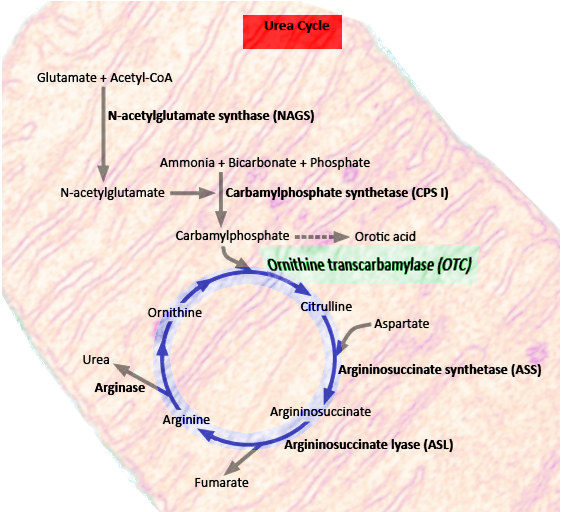

Ornithine transcarbamylase is a critical enzyme in the urea cycle. The urea cycle converts nitrogenous waste into urea. Urea is water soluble, allowing for its excretion from the body via urination. The OTC enzyme is involved in arginine biosynthesis.[8] It converts carbamoyl phosphate and ornithine into citrulline.[1]

History and Physical

OTC deficiency is not part of routine neonatal screening or testing. Since it is genetic, it is useful to ask about family medical history. Signs of OTCD in neonates include tachypnea, vomiting, and lethargy within the first day of life.[9]

In the late-onset form of OTCD, symptoms are vague and variable at first. These symptoms include lethargy, loss of appetite, early morning headaches, and confusion.[2] Unfortunately, delayed diagnosis can lead to more severe complications. Advanced OTCD leads to severe behavioral symptoms, neurological symptoms, and acute liver failure. Advanced OTCD symptoms include seizures, aggressive behavior, encephalopathy, coma, and death.[4] Due to the late and gradual onset of OTCD in females, and multiple much more common etiologies of encephalopathy, this condition is often not considered initially.

Evaluation

The clinician should suspect OTC deficiency in patients with elevated ammonia and liver function tests. Ammonia above 200 micromol/L suggests an inherited metabolic disease.[9] Since the OTC enzyme is early in the urea cycle, OTCD will acutely have higher ammonia levels than most of the other urea cycle disorders. On further investigation, there will be low blood citrulline level and high urinary orotic acid.[5] In addition to genetic testing, liver biopsy can frequently confirm an OTC deficiency diagnosis.

MRI will not always be helpful. In an acute presentation, cerebral edema may be present. Chronic findings of OTC on MRI are cortical atrophy, white matter cysts, and decreased myelin.[10] Enzyme analysis and molecular genetic testing can identify OTC deficiency as the underlying cause of the patient’s symptoms.

Treatment / Management

Treatment includes hydration, arginine, and hemodialysis.[2] Arginine supplementation bypasses the OTC enzyme in the urea cycle, allowing for urea creation and ammonia elimination. Using a combination of sodium benzoate and sodium phenylbutyrate reduces ammonia by using alternative pathways for nitrogen elimination. If ammonia rises above 500 micromol/L, the patient should receive urgent hemodialysis. Ammonia levels above 800 micromol/L are associated with severe neuralgic damage, limiting treatment options.[9] Once OTCD is suspected, genetic counseling can be helpful for patients and their families. To prevent their condition from deteriorating, patients should limit their protein intake and will benefit from a vegetarian diet. Reports exist of instances of late-onset disease, where patients follow a vegetarian diet before their OTCD diagnosis because protein had become associated with headaches.

Differential Diagnosis

It is imperative to distinguish ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency from other genetic disorders that cause hyperammonemia. Hyperammonemia can be caused by other urea cycle disorders as well as by organic acidemias, defects of fatty oxidation and disorders of pyruvate metabolism. Signs in the patient's bloodwork that limit the differential to a urea cycle disorder will include respiratory alkalosis with a normal anion gap, normal blood sugar levels, and severe ammonia levels on the order of 1000micromol/L.[11] Patients with OTC deficiency, in particular, will have higher ammonia levels than patients with other urea cycle disorders caused by enzyme deficiencies later in the urea cycle.

Prognosis

Ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency causes high mortality and morbidity, particularly in males since they are hemizygous for the X-linked mutation. Fifty percent of infants perish. Even if an infant survives a hyperammonemic coma, they will probably face intellectual disabilities if they were in the coma for over 24 hours.[10] Patients diagnosed early and treated emergently have an improved prognosis as do patients who adhere to low protein diets and take medications that bypass the OTC enzyme in the urea cycle. Patients with late-onset OTC deficiency have better outcomes since they may have some functional OTC enzyme. More research is underway to determine the long-term prognosis of patients who adhere to OTC management protocols.

Complications

If physicians fail to diagnose OTCD timely and a patient is untreated for long, severe complications ensue. Acute complications vary but include acute liver failure and severe hyperammonemic encephalopathy.[4] Patients may progress into a coma and require mechanical ventilation due to acute respiratory failure. Long-term complications include intellectual, neurological and physical disabilities.[12] Eventual death occurs if OTCD left untreated for too long.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Prevention and immediate treatment prevent mortality and reduce morbidity from OTC deficiency. The diagnosing physician should refer an OTCD patient and his/her family to a biochemical geneticist as they will need genetic counseling. OTCD patients should reduce their dietary protein and maintain adequate hydration. Certain medications should be avoided, such as steroids that increase protein breakdown into nitrogenous waste. OTCD patients should not take valproic acid even if they have seizures since valproic acid inhibits the urea cycle. These considerations will prevent the buildup of ammonia and reduce OTCD complications.

Pearls and Other Issues

Ornithine transcarbamylase is an enzyme in the urea cycle, and lack of it can lead to toxic levels of ammonia. Although OTC deficiency is the most common of the urea cycle disorders, it is a rare disease. Signs and symptoms of OTC deficiency present earlier in males since the genetic code for this enzyme is on the X-chromosome. Symptoms are variable, initially vague, and present later in life for females. Early recognition and treatment can prevent severe or lethal outcomes.[4] Failing to refer families to genetic counseling could be disastrous for the patient and others in their family. Ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency goes undetected on neonatal screening. Dietary guidance and regular follow-up are imperative for patients diagnosed with OTC deficiency.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Given that this is a rare and potentially lethal condition, a knowledgeable team member could have a dramatic impact on the patient’s outcome. Additionally, since this is a genetic condition, helping one patient helps others in their family. Members of the patient’s care team work together to make this diagnosis, firstly by having a low threshold for suspicion that vague behavioral and neurologic signs and symptoms may underlie a metabolic condition. Symptoms may first be discovered by nurses monitoring a patient’s vitals, by the patient’s parents or the patient themselves. Pediatricians, internists, or family physicians should have a low threshold for suspicion to test ammonia levels in patients presenting with neurological or behavioral disturbances. Given these presenting symptoms, specialists such as psychiatrists, neurologists, and radiologists play a role in diagnosis. Hemodialysis is an option for emergent treatment; thus nephrologists should be consulted immediately. Geneticists, pharmacists, and dieticians play key roles in treating these patients in the short and long term. It is the ethical responsibility of the care team to recommend genetic counseling to the patient or their family since carrying this mutation will affect not only their lives but also the lives of their relatives. This condition is treatable if caught early and fatal or debilitating if left undiagnosed.