Os Odontoideum

- Article Author:

- Matias Pereira Duarte

- Article Author:

- Joe M Das

- Article Editor:

- Gaston Camino Willhuber

- Updated:

- 10/13/2020 11:15:16 AM

- For CME on this topic:

- Os Odontoideum CME

- PubMed Link:

- Os Odontoideum

Introduction

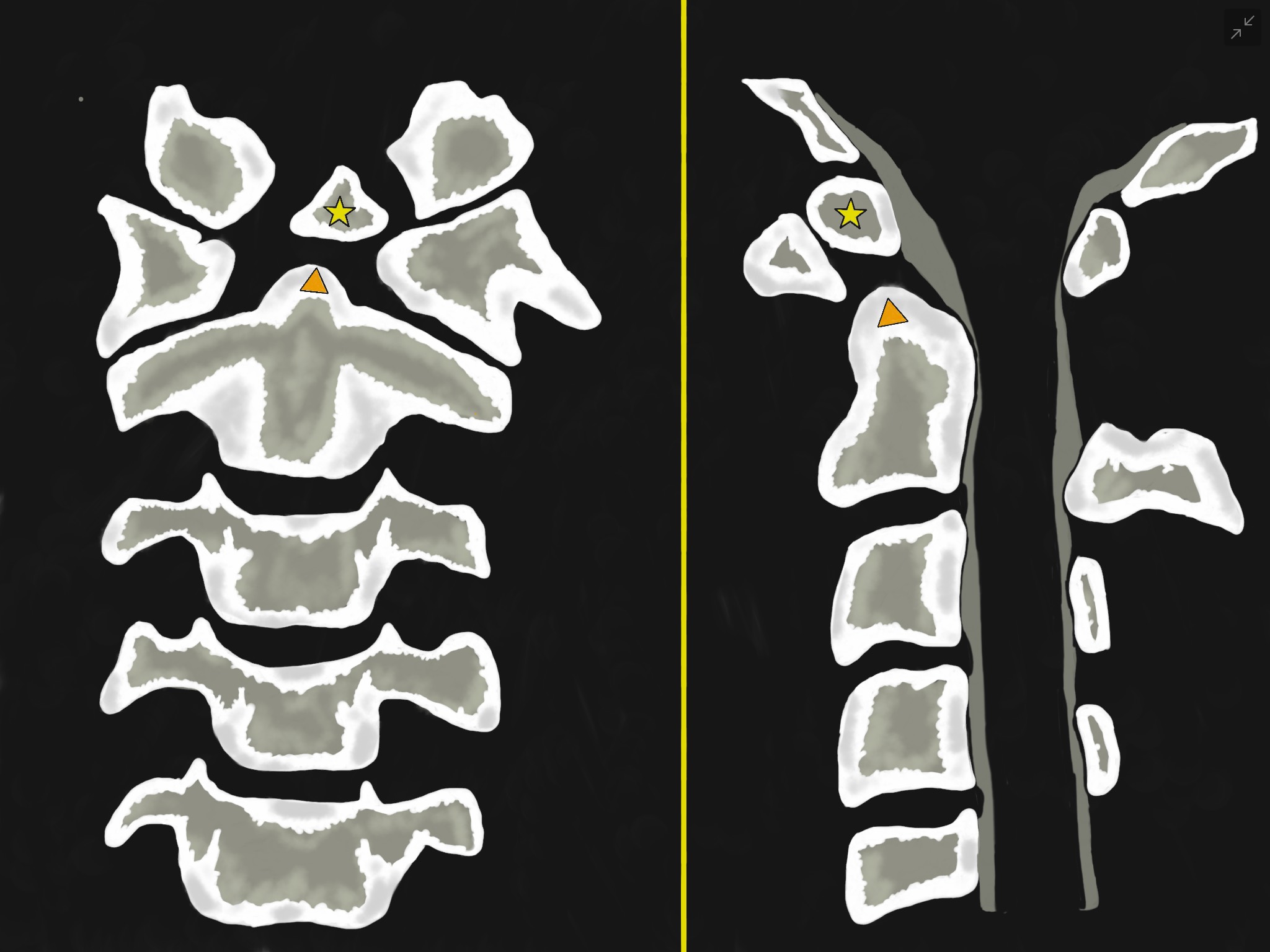

The term os odontoideum (OO) refers to an anatomic anomaly of the upper cervical spine which was first described by Giacomini in 1886.[1] This condition is defined radiologically as an oval or round-shaped ossicle with smooth circumferential cortical margins representing a hypoplastic odontoid process (dens) that has no continuity with the C2 vertebral body.[2][3][4] (See Figure). The ossicle is usually cranially migrated relative to the expected position of the odontoid tip and can adopt two anatomic types: orthotopic (ossicle located in the position of the normal odontoid) and dystopic (ossicle located near the occiput in the area of the foramen magnum).[5][6]

Researchers have described variable radiological sizes regarding OO. However, most present half the size of a normal odontoid process, some are so small and cephalic that it may be hard to diagnose on plain X-rays or computed tomography (CT).[4] The OO is often attached to the anterior arch of C1 through an intact transverse ligament.

One of the main risks of this anatomical entity is the association of anterior atlantoaxial subluxation. Posterior atlantoaxial subluxation is extremely rare.[7] This atlantoaxial instability can lead to cervical spinal stenosis with resultant cervical myelopathy due to vascular compromise, bony compression, and/or stretching of the spinal cord.[8]

Etiology

The etiology/pathogenesis of this lesion remains controversial. However, there are two theories about the origin of os odontoideum: traumatic or congenital.

Most studies favor the hypothesis of the traumatic theory, considering it as an acquired pathology resulting from avascular necrosis caused by an odontoid fracture. The acquired theory purports that the os odontoideum forms after a traumatic event, with the preservation of the blood supply to the fractured odontoid tip; this can occur in either the prenatal or postnatal periods, and therefore may not be recalled by the patient.[9][10][11][12] There have been case reports documenting the formation of an os odontoideum after trauma in patients with previously documented normal odontoid processes.[13][14][15]

On the other hand, the congenital hypothesis considers it a segmental defect, which represented a failed fusion of odontoid and axis vertebral body,[16][17][18] an incomplete migration of the axis centrum, failure of segmentation, and/or nontraumatic avascular necrosis.[19] The congenital theory may explain os odontoideum in identical twins without a history of trauma or reports of familial expression.[20][21][9][22]

This thought line is reinforced by Straus et al., who demonstrated trends in gene expression profiles between os odontoideum patients and normal subjects.[23]

The congenital theory has support from certain associations with upper cervical anomalies such as hypoplastic posterior arch of C1, Klippel-Feil syndrome, trisomy 21 syndrome, Morquio syndrome, or neurofibromatosis.[9]

Epidemiology

Os odontoideum is a rare entity with an unknown estimated prevalence due to the usual asymptomatic course and the absence of large-scale screening studies.

It is usually found in the pediatric population being incidentally detected in asymptomatic patients or diagnosed in symptomatic patients at adult age.[4][6]

Perdikakis et al.[24] retrospectively reviewed the magnetic resonance (MR) of the odontoid process configuration in 133 patients, aged between 19 and 81 years old, finding OO in one case (0.7%).

Pathophysiology

Embryological pathophysiologic development[25]:

Ossiculum terminale or the apical odontoid epiphysis: Odontoid apex is derived from the fourth occipital sclerotome

The odontoid and axis bodies: Develop from the first and second cervical sclerotomes

Neurocentral synchondrosis: The epiphyseal growth plate that separates the first and second cervical sclerotomes

Terminal apical arcade of blood vessels - The odontoid process depends on this arcade mostly for its blood supply and this anastomoses caudally with the deep penetrating branches arising from the posterior ascending arteries. The latter arise from the vertebral artery. Since the blood supply to the odontoid is precarious in this way, any vascular insufficiency of the terminal arcade can lead to ischemia and necrosis during embryologic development.

History and Physical

Clinical presentation may vary widely, ranging from asymptomatic incidental findings on imaging to neck discomfort and/or neurological deficits with permanent paralysis in severe cases.[8]

Its initial clinical presentation is often nonspecific with neck pain, shoulder pain, torticollis or headache and upper extremity paresthesia like intermittent tingling and numbness in the neck and upper limbs. Other common complaints are lower limb weakness and gait difficulties.[9] These symptoms are thought to result from static or dynamic compression or repeated minor trauma to the spinal cord.[26]

Increased motion at the C1-C2 level can lead to vertebral artery occlusion, ischemia of the brainstem and posterior fossa structures, resulting in seizures, syncope, vertigo, visual disturbances and even sudden death after minor trauma.[27][28][29][30][31]

During the physical examination, it is common to find neurological deficits or loss of motors milestones. Hypoesthesia, hyperreflexia (patellar tendon reflex), scapulohumeral (Shimizu) reflex, Tromner reflex, Hoffmann reflex, Babinski reflex, and clonus may result in positive in chronic spinal cord compression.[6] Spastic or broad-based gait and decreased hand dexterity are signs of myelopathy. All those previous sings and symptoms are nonspecific, and usually, another diagnosis that causes myelopathy should be ruled out.

Evaluation

Early and accurate diagnosis is critical in mitigating morbidity and mortality. Minor trauma in undiagnosed cervical instability might end in catastrophic neurological results.

Routine anteroposterior and lateral cervical spine radiographs with an open-mouth odontoid are the first approach to this condition and can make the diagnosis.

Lateral radiograph of the cervical spine demonstrates widening of the anterior atlantoaxial distance and disruption of the spinolaminar junction line posteriorly. A well-corticated rounded ossicle located just dorsal and slightly cranial to the anterior arch of C1 presents in this projection without prevertebral soft tissue widening. Cervical spine flexion-extension radiographs help to determine the degree of atlantoaxial instability.[27]

Some authors also perform bedside lateral radiographs during preoperative skull traction as they consider them to be very important for atlantoaxial joint instability and subluxation, and could help determine the surgical method used.[32]

Computed tomography images confirm the corticated margin of this ossicle. It shows a shortened odontoid process and a smooth ossicle of bone. Reconstruction of CT images may show the congenital incomplete union of the C1 posterior arch.[9] A hypertrophied anterior arch of C1 often suggests underlying chronic instability.[33]

CT scan is also used to assess anatomical landmarks, as well as length and direction of the pedicles and vascular anatomy (VA), especially for the presence or absence of an anomalous VA.[32]

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrates fluid within the widened anterior atlantoaxial space. It is possible to find a focal narrowing of the spinal canal with the posteriorly tilted odontoid process abutting the ventral cervical spinal cord, which may contain some areas of increased T2-weighted signal within the central gray matter, most consistent with myelomalacia.[8]

There are some measurements taken at the lateral cervical radiographs or at the sagittal CT reconstruction that can help us to define cervical instability or surgical approach (See Figure).

- The atlanto-dental interval (ADI) is the distance between the odontoid process and the posterior border of the anterior arch of the atlas. In adults, a value greater than 3.5 mm is considered unstable, and more than 10 mm indicates surgery, while in pediatrics it is normal up to 5 mm.[6]

- Space-available-cord (SAC) or posterior atlanto-dens-interval (PADI) is the distance between the posterior surface of dens and the anterior surface of the posterior arch of the atlas. In adults, a value of less than 14 mm is associated with an increased risk of neurologic injury and is an indication for surgery.[34]

Treatment / Management

Treatment options vary from no therapy and control to surgical treatment depending on symptoms and atlantoaxial instability, assessed by radiological images.

For asymptomatic patients, there is an ongoing debate between conservative therapies with imaging follow-up versus prophylactic spinal fusion.[8] In cases without symptoms and no evidence of C1–C2 instability, regular clinical and radiographic follow-up, with avoidance of all contact sports is recommended.[32]

Meanwhile, asymptomatic patients with radiographic evidence of atlantoaxial instability need to consider surgery, although there is a controversy regarding whether C1–C2 fusion can significantly influence neck rotation and daily activities of patients. Although the procedure could induce the loss of normal neck rotation by as much as 50%, the remaining joints could compensate for most of the function of C1–C2. The benefits of avoiding neurological compromise secondary to cord compression outweigh the loss of neck rotation associated with this procedure.[32]

All symptomatic patients are candidates to undergo surgical treatment.[8][9][35]

Surgery is usually indicated in patients who had one of the following conditions: neurological involvement (even if this is transient), radiological signs of instability (more than 5 mm of translation in flexion and extension X-rays), progressive instability, persistent neck pain associated with atlantoaxial instability.[7]

The principles of treatment are to prevent sudden death from neurological compromise, improve the neurological status, stabilize the cervical spine, and improve the quality of life.

The treatment strategies for this condition can be resume in four steps:

- Determine the main pathology causing the symptoms of myelopathy (i.e., odontoid peg, posterior arch of C1).

- Define whether the atlantoaxial subluxation is reducible or not.

- Decide whether the lesion requires decompression or not.

- Select the surgical option for stabilization and fusion.

Surgical options include atlantoaxial fusion, occiput-C2 fusion, and occiput-C3 fusion.[26][36] The decision depends on spinal cord compression location, area for arthrodesis, and bone quality.[7] All of them can be complemented with an additional transoral decompression in cases of irreducible subluxation of C1–C2.[37][38] However, this procedure often has accompanying complications such as wound infection, cerebrospinal fluid leakage, neurological injury, and hardware loosening.

Occipito-cervical fusion is indicated in occipito-cervical instability or failed attempt of atlantoaxial fusion, also suggested in cases of poor bone quality due to the increased risk of screw pull-out.[39][40]

Summary of treatment options:

- Clinically asymptomatic os odontoideum - Clinical and radiographic surveillance or posterior C1-C2 internal fixation and fusion

- Symptomatic os odontoideum or C1-C2 instability - Posterior C1-C2 internal fixation and fusion

- If rigid C1-C2 fixation is not achievable - Postoperative halo immobilization

- Os odontoideum with irreducible dorsal cervico-medullary compression with or without occipito-atlantal instability - Occipital-cervical fixation and fusion with or without C1 laminectomy

- Irreducible ventral cervico-medullary compression - Ventral decompression

Differential Diagnosis

OO is one of the causes of atlantoaxial instability and dislocation,[9] the differential diagnosis that can produce this instability should be ruled out, such as:

- Acute dens fracture, an acute fracture would have a thinner and irregular space instead of the wide and smooth space of os odontoideum.

- Dens morphologic abnormalities (aplasia of the dens, bifid dens, dens duplicated, ossiculum terminale persistens).[41]

- Down Syndrome

- Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis

- Klippel–Feil syndrome

- Morquio syndrome

- Neurofibromatosis

- Normal development in the pediatric population. In pediatrics, awareness of the normal embryology and ossification of the odontoid process is critical to reducing the rate of false-positive diagnoses. The apex of the odontoid arises from the fourth occipital sclerotome, the odontoid process and anterior arch of C1 arise from the first cervical sclerotome, and the body of the axis arises from the second sclerotome. The apex (ossiculum terminale, secondary ossification center) ossifies at around ages 3 to 6 years but does not fuse with the body of the odontoid until approximate ages of 10 to 12 years. The normal sub-dental synchondrosis is between the odontoid and the body of C2 and fuses at approximately ages 3 to 8 years.[20][19][36]

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Transverse ligament injury

Prognosis

The prognosis of this condition may vary according to symptoms and radiological parameters previously mentioned. The definition of C1-C2 instability is greater than 3 mm of anterior and posterior displacement of the atlas on the axis in adults and more than 4 to 5 mm in children.[6] Greater displacement predicts the poorest outcomes. The degree of atlantoaxial instability is less sensitive than the absolute diameter of the spinal canal in predicting poor outcomes.[28][2] On the other hand, a posterior atlanto-dens interval (PADI) less than 12 mm is a predictor for the development of paralysis in all causes of C1-C2 instability.[34]

Complications

Complications of this entity rely on the severity of cord compression, instability, and unexpected events since minor trauma can lead to catastrophic neurological damage, including sudden death. This risk is due to the potential risk of C1-C2 instability secondary to abnormal development of the dens. Proper detection of radiological signs of instability is imperative to avoid complications related to spinal cord compression.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Upon arriving at the diagnosis of symptomatic os odontoideum, surgical treatment should be a consideration. Conservative treatment is an option only when the patient is asymptomatic, and there is no evidence of atlantoaxial instability. The patients should be aware of the possible catastrophic consequences of this pathology. Regular clinical and radiographic follow-up is necessary, and clinicians should strongly advise the avoidance of all contact sports.

If the patient points out any symptoms relative to this condition, or there is radiological evidence of C1-C2 instability, surgery is the most appropriate treatment.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Os odontoideum is an uncommon diagnosis. However, early recognition and proper identification of radiological and clinical signs of instability may help to avoid catastrophic complications secondary to spinal cord compression. Once the physician has confirmation of the diagnosis, patients and their families require education from the surgeon and orthopedic nurses about this condition and its possible outcomes.

Os odontoideum requires an interprofessional team approach, including physicians, surgeons, specialists, and specialty-trained nurses, all collaborating across disciplines to achieve optimal patient results. [Level V]

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Figure 1 - Illustrations of Os Odontoideum in an anterior-posterior (left-sided image) and lateral (Right-sided image) views. They show an oval or round-shaped ossicle with smooth circumferential cortical margins (yellow star) representing a hypoplastic odontoid process (Orange triangle) that has no continuity with the C2 vertebral body. It often attached to the anterior arch of C1 through an intact transverse ligament.

Contributed by Franco De Cicco, MD

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Figure 1 - Illustration that represents an upper cervical spine lateral view. It shows an oval or round-shaped ossicle with smooth circumferential cortical margins representing a hypoplastic odontoid process that has no continuity with the C2 vertebral body. The atlanto-dens interval (ADI) (orange star) is the distance between the odontoid process and the posterior border of the anterior arch of the atlas. The space-available-cord (SAC) or posterior atlanto-dens-interval (PADI) (orange triangle) is the distance between the posterior surface of dens and the anterior surface of the posterior arch of the atlas.

Contributed by Franco De Cicco, MD.