Osteoarthritis

- Article Author:

- Rouhin Sen

- Article Editor:

- John Hurley

- Updated:

- 3/30/2020 9:14:02 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Osteoarthritis CME

- PubMed Link:

- Osteoarthritis

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common form of arthritis in the world. It can be classified into 2 categories: primary osteoarthritis and secondary osteoarthritis. Classically, OA presents with joint pain and loss of function; however, the disease is clinically very variable and can present merely as an asymptomatic incidental finding to a devastating and permanently disabling disorder.[1][2][3]

Etiology

Risk factors for developing OA include age, female gender, obesity, anatomical factors, muscle weakness, and joint injury (occupation/sports activities).

Primary OA is the most common subset of the disease and is diagnosed in the absence of a predisposing trauma or disease but is associated with the risk factors listed above.

Secondary OA occurs with preexisting joint abnormality. Predisposing conditions include trauma or injury, congenital joint disorders, inflammatory arthritis, avascular necrosis, infectious arthritis, Paget disease, osteopetrosis, osteochondritis dissecans, metabolic disorders (hemochromatosis, Wilson’s disease), hemoglobinopathy, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, or Marfan syndrome.[4][5]

Epidemiology

OA affects about 3.3% to 3.6% of the population globally. It causes moderate to severe disability in 43 million people making it the 11th most debilitating disease around the world. In the United States, it is estimated that 80% of the population over 65 years old has radiographic evidence of OA, although only 60% of this subset has symptoms. This is because radiographic OA is at least twice as common as symptomatic OA. Therefore, changes on radiograph do not prove that OA is the cause of the patient’s joint pain. In 2011, there were almost 1 million hospitalizations for OA with an aggregate cost of nearly $15 billion making it the second most expensive disease seen in the United States. [1][3]

Pathophysiology

OA is a disease of the entire joint sparing no tissues. The cause of OA is an interplay of risk factors (mentioned above), mechanical stress, and abnormal joint mechanics. The combination leads to pro-inflammatory markers and proteases that eventually mediate joint destruction. The complete pathway that leads to the destruction of the entire joint is unknown.

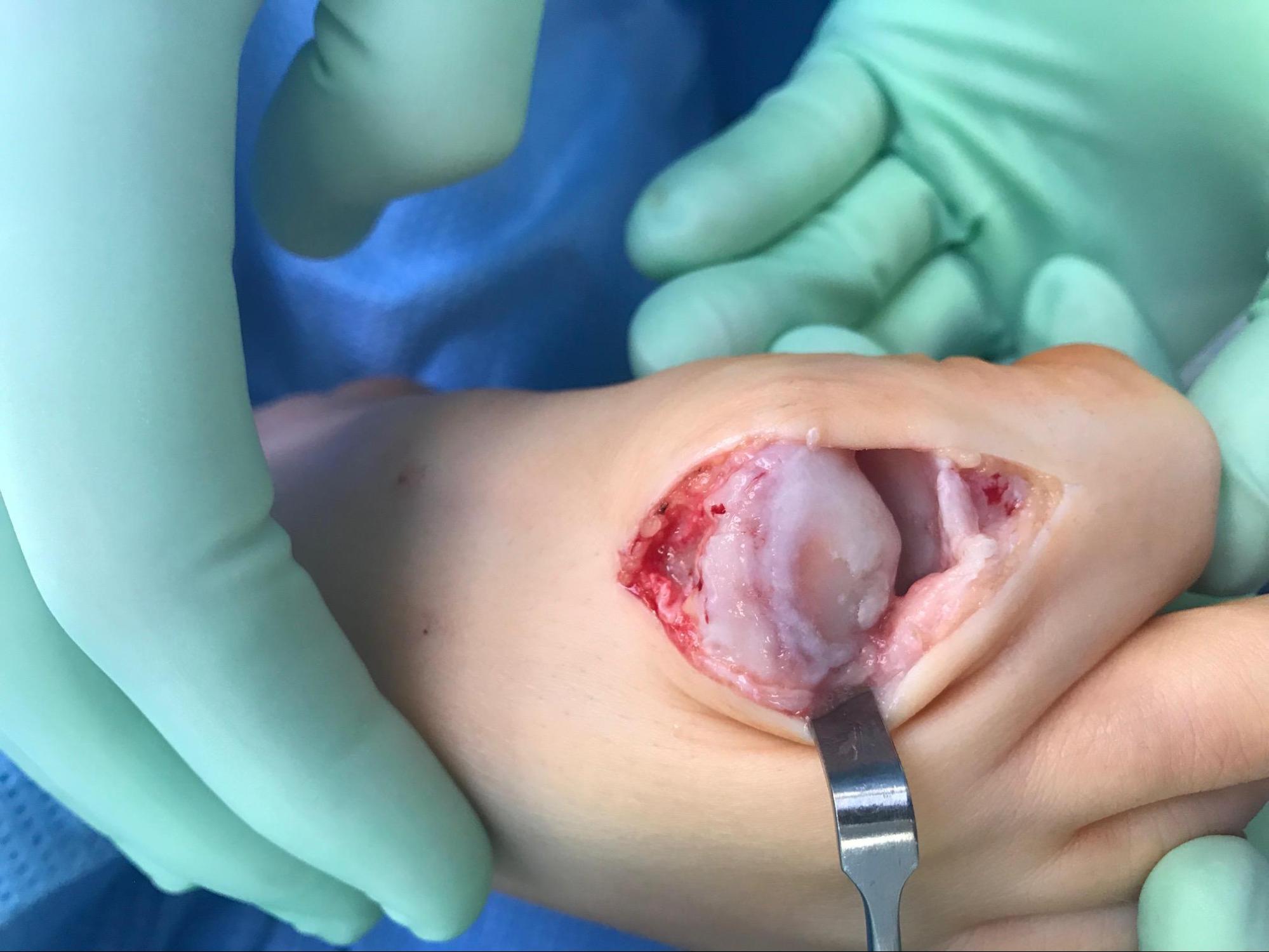

Usually, the earliest changes in OA are at the level of the articular cartilage that develops surface fibrillation, irregularity, and focal erosions. These erosions eventually extend down to the bone and continually expand to involve more of the joint surface. On a microscopic level, after cartilage injury, the collagen matrix is damaged causing chondrocytes to proliferate and form clusters. A phenotypic change to hypertrophic chondrocyte occurs causing cartilage outgrowths that ossify and form osteophytes. As more of the collagen matrix is damaged, chondrocytes undergo apoptosis. Improperly mineralized collagen causes subchondral bone thickening; in advanced disease, bone cysts infrequently occur. Even rarer, bony erosions appear in erosive OA.

There is also some degree of synovial inflammation and hypertrophy although this is not the inciting factor as it is for inflammatory arthritis. Soft tissue structures (ligaments, joint capsule, menisci) are also affected. In end-stage OA, both calcium phosphate and calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystals are present. Their role is unclear, but they are thought to contribute to synovial inflammation.[6][7][8]

History and Physical

The presentation and progression of OA vary greatly from person to person. The triad of symptoms of OA is joint pain, stiffness, and locomotor restriction. Patients can also present with muscle weakness and balance issues.

Pain is typically related to activity and resolves with rest. In those patients in whom the disease progresses, pain is more continuous and begins to affect activities of daily living, eventually causing severe limitations in function. Patients may also experience bony swelling, joint deformity, and instability (patients complain that joint is “giving way” or “buckling,” a sign of muscle weakness).

OA typically affects proximal and distal interphalangeal joints, first carpometacarpal (CMC) joints, hips, knees, first metatarsophalangeal joints, and joints of the lower cervical and lumbar spine. OA can be monoarticular or polyarticular in the presentation. Joints can be at different stages of disease progression. Typical exam findings in OA include bony enlargement, crepitus, effusions (non-inflammatory), and limited range of motions. Tenderness may be present at joint lines, and there may be pain upon passive motion. Classic physical exam findings in hand OA include Heberden’s nodes (posterolateral swellings of DIP joints), Bouchard’s nodes (posterolateral swellings of PIP joints), and “squaring” at the base of the thumb (first CMC joints).

Evaluation

A thorough history and physical exam (with focused musculoskeletal exam) should be done in all patients with some findings summarized above. OA is a clinical diagnosis and can be diagnosed with confidence if the following are present: 1) pain worse with activity and better with rest, 2) age > 45 years, 3) morning stiffness lasting less than 30 minutes, 4) bony joint enlargement, and 5) limitation in range of motion. A differential diagnosis should include rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, crystalline arthritis, hemochromatosis, bursitis, avascular necrosis, tendinitis, radiculopathy, among other soft tissue abnormalities.[9][10]

Blood tests such as CBC, ESR, rheumatoid factor, ANA are usually normal in OA although they may be ordered to rule out inflammatory arthritis. If the synovial fluid is obtained, the white blood cell count should be <2000/uL, predominantly mononuclear cells (non-inflammatory) to be consistent with a diagnosis of OA.

X-rays of the affected joint can show findings consistent with OA such as marginal osteophytes, joint space narrowing, subchondral sclerosis, and cysts; however, radiographic findings do not correlate to the severity of disease and may not be present early in the disease. MRI is not routinely indicated for OA workup; however, it can detect OA at earlier stages than normal radiographs. Ultrasound can also identify synovial inflammation, effusion, and osteophytes which can be related to OA.

There are several classification systems for OA. In general, they include the joints affects, the age of onset, radiographic appearance, presumed etiology (primary vs. secondary), and rate of progression. The American College of Rheumatology classification is the most widely used classification system. At this time, it is not possible to predict which patients will progress to severe OA and which patients will have their disease arrest at earlier stages.

Treatment / Management

Treatment goals for OA are to minimize both pain and functional loss. Comprehensive management of the disease involves both non-pharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies. Typically, patients with mild symptoms can be managed by the former while more advanced diseases need a combination of both.[11][12][13]

Mainstays for non-pharmacologic therapy includes 1) avoidance of activities exacerbating pain or overloading joint, 2) exercise to improve strength, 3) weight loss, and 4) occupational therapy for unloading of joint via brace, splint, cane, or crutch. Weight loss is an extremely important intervention in those who are overweight and obese; each pound of weight loss can decrease the load across the knee 3 to 6-fold. Formal physical therapy can help immensely in assisting patients on how to use equipment such as canes appropriately while also instructing them on exercises. Exercise programs that combine both aerobic and resistance training have been shown to decrease pain and improve physical function in multiple trials and should be encouraged by physicians regularly. Malalignment of joints should be corrected via mechanical means such as realignment knee brace or orthotics.

Pharmacotherapy of OA involves oral, topical, and/or intra-articular options. Acetaminophen and oral NSAIDs are the most popular and affordable options for OA and are usually the initial choice of pharmacologic treatment. NSAIDs are usually prescribed orally or topically and initially, should be started as needed rather than scheduled. Due to gastrointestinal toxicity, and renal and cardiovascular side effects, oral NSAIDs should be used very cautiously and with close monitoring long term. Topical NSAIDs are less efficacious than their oral counterparts but do offer fewer gastrointestinal and other systemic side effects; however, they often cause local skin irritation.

Intra-articular joint injections can also be an effective treatment for OA, especially in a setting of acute pain. Glucocorticoid injections have a variable response, and there is ongoing controversy regarding repeated injections. Hyaluronic acid injections are another option, but their efficacy over placebo is also controversial. Notably, there is no role for oral glucocorticoids.

Duloxetine has modest efficacy in OA; opioids can be used in those patients without adequate response to above and who may not be candidates for surgery or refuse it all together.

It is important to note that patients vary greatly in their response to treatment, and there is a large component of trial and error in selecting the agents that will be most effective. In those patients specifically with knee or hip OA who have failed multiple non-pharmacologic and pharmacologic treatment modalities, surgery is the next option. Failure rates for both knee and hip replacements are quite low, and they can provide pain relief and increased functionality. The timing of surgery is key to predict success. Very poor functional status and considerable muscle weakness may not lead to improved post-operative functional status compared to those patients undergoing surgery earlier in the disease course.[14][15]

Differential Diagnosis

A differential diagnosis should include rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, crystalline arthritis, hemochromatosis, bursitis, avascular necrosis, tendinitis, radiculopathy, among other soft tissue abnormalities.

Complications

- Pain

- Falls

- Difficulty ambulation

- Joint malalignment

- Decreased range of motion of the joint

- Radiculopathies

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Lifestyle changes - especially enrollment in exercise and weight reduction

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Osteoarthritis is a chronic progressive disorder that affects millions of people with advancing age. The condition has no cure and is managed by a team of healthcare professionals that include an internist, radiologist, endocrinologist, orthopedic surgeon, and a rheumatologist. The nurse, pharmacist and the physical therapist are also integral members of the team. Patients with osteoarthritis need to be educated on the natural history of the disease and understand their treatment options. Obese patients need a dietary consult and enroll in an exercise program. Evidence shows that water-based activities can help relieve symptoms and improve joint function, hence consultation with a physical therapist is recommended. Further, many of these patients may benefit from a walking aid. Patients with pain should become familiar with the types of drugs and supplements available and their potential adverse effects. Only through education of the patient can the morbidity of this disorder be decreased.[16][17][18] (Level V)

Evidence-Based Outcomes

The prognosis for patients with osteoarthritis depends on the joint involved, how many joints are involved and the severity. There is no cure for osteoarthritis and all the currently available treatments are all directed towards the reduction of symptoms. Factors associated with rapid progression of the disease include obesity, advanced age, multiple joint involvement and presence of varus deformity. Patients who undergo joint replacement tend to have a good prognosis with success rates over 80%. However, most of the prosthetic joints wear out in 10-15 years and repeat surgery is required. Also of importance is that patients must undergo preoperative workup as the post-surgical complications can be serious and disabling.[19][20][21] (Level V)