Otalgia

- Article Author:

- Jessica Coulter

- Article Editor:

- Edward Kwon

- Updated:

- 8/15/2020 11:14:32 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Otalgia CME

- PubMed Link:

- Otalgia

Introduction

Otalgia (ear pain) divides into two broad categories: primary and secondary otalgia. Primary otalgia is ear pain that arises directly from pathology within the inner, middle, or external ear. Secondary or referred otalgia is ear pain that occurs from pathology located outside the ear. A complex neural network innervates the ear as a result of complex embryologic development. The ear shares this neural network with other organs, which leads to numerous potential causes of referred ear pain.[1]

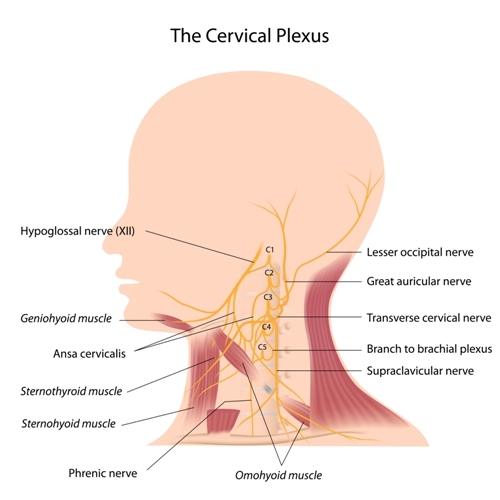

Cranial nerves V (trigeminal), VII (facial), IX (glossopharyngeal), X (vagus), and branches from the cervical plexus (C2 and C3) all innervate the ear.[2][3]

- The auricle is innervated by cranial nerves V, VII, X, C2, and C3.

- The ear canal is innervated by cranial nerves V, VII, and X.

- The tympanic membrane is innervated by cranial nerves VII, IX, and X.

- The middle ear is innervated by cranial nerves V, VII, and IX.

Cranial nerves V, VII, IX, X, C2, and C3 also innervate organs outside of the ear, leading to numerous potential causes of referred ear pain.

- Cranial nerve V (trigeminal) is composed of the ophthalmic (V1), maxillary (V2), and mandibular (V3) branches. It provides sensory innervation for the face, sinuses, palate, and teeth. The auriculotemporal branch of cranial nerve V innervates the temporomandibular joint (TMJ). This branch is most commonly implicated in temporomandibular joint disease. Dental and TMJ pathology are common secondary causes of otalgia.

- Cranial nerve VII (facial) innervates the anterior two-thirds of the tongue, sublingual, and submandibular salivary glands. It also innervates the muscles of facial expression.

- Cranial nerve IX (glossopharyngeal) innervates the posterior third of the tongue, carotid body, and oropharynx.

- Cranial nerve X (vagus) innervates the sinuses, thyroid gland, pharynx, and larynx. The superior laryngeal branch of the vagus nerve innervates the vocal cords. It also innervates distant organs such as the heart, lung, and parts of the gastrointestinal tract.

- C2 and C3, which are branches of the cervical plexus, innervate the back of the head, sternocleidomastoid, and cervical paraspinal muscles.

Etiology

Otalgia classifies into primary versus secondary or referred causes. The differential diagnosis is extensive and receives more detailed coverage below. Thus, a comprehensive and systematic approach to otalgia is essential. Primary otalgia classifies into infectious, mechanical, neoplastic, and inflammatory causes. Secondary otalgia is best classified based on organ systems. More proximal causes of the head and neck include dental and temporomandibular pathology. Distant etiologies include cardiac, gastrointestinal, and lung pathology.

Epidemiology

Ear complaints are a relatively common complaint in primary care.[4][3] Otalgia divides into primary and secondary or referred causes. The 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10), contains no specific code for primary otalgia or secondary otalgia. There is a formal classification in the medical literature. However, medical coding does not reflect this. No recent studies in the United States have delineated a precise ratio of primary to secondary otalgia.

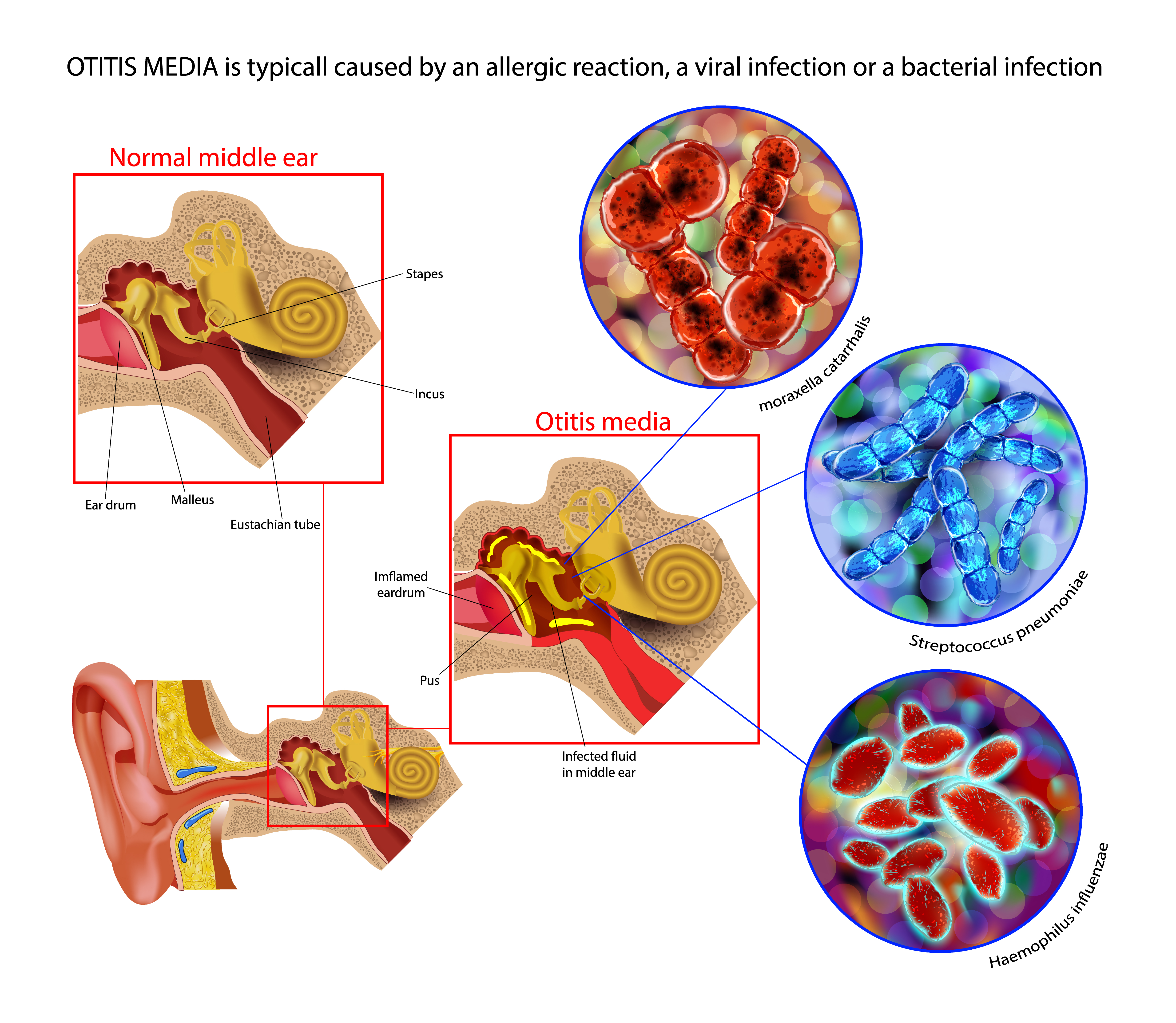

Overall, primary causes tend to be more common. Men tend to have a primary cause, while women tend to have a secondary cause.[5][6] The majority of pediatric cases of otalgia are primary, with acute otitis media (AOM) being the most common.[5] One study stated that 80% of children would have otitis media before three years of age [7]. Acute otitis media (AOM) has a significant disease burden in the United States. From 1997 to 1999, it accounted for 9.5% of all outpatient visits for children. Streptococcus pneumoniae caused most cases of AOM. In 2000 and 2010, PCV-7 and PCV-13 vaccines were released to provide immunity against Streptococcus pneumoniae. After their release, the percent of outpatient visits for AOM decreased from 9.5% to 5.5% from 2012 to 2014. Non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae took over as the most common cause of AOM.[8] A vaccine exists for encapsulated Haemophilus influenzae Type B, but not yet for the non-typable strain (unencapsulated).

While primary causes tend to be more common, two studies stated that secondary causes account for nearly 50% of cases of otalgia.[1][9] Adults and women with otalgia are more likely to have a secondary cause.[5][3][4][6] While the literature is inconsistent, temporomandibular, and dental pathology tends to get cited as the most common causes of secondary otalgia.[1][4][6] While dental pathology tends to get cited as the most common cause, one article published in Ireland mentioned that mechanical disorders of the neck and jaw were much more common.[10] Patients over 65 years of age are more likely to experience otalgia from cervical spine disease.[2] Women 20 to 40 years old are more likely to experience temporomandibular joint disease.[11] Malignancies or distant secondary causes such as thyroid cardiac, gastrointestinal, or lung pathology are rare. Other secondary etiologies, such as petrous apicitis, malignant otitis externa, and Eagle syndrome, are also uncommon.

Pathophysiology

Primary otalgia occurs most commonly from infection. Acute otitis media (AOM) ranks as the number one cause of primary otalgia in children. The disease is typically associated with an upper respiratory tract infection that causes congestion and swelling of the eustachian tube. Between the middle ear and the eustachian tube, there is a narrowing of the eustachian tube called the bony-cartilaginous junction or isthmus. The swelling of the eustachian tube at this location can prevent the middle ear drainage. This collection of middle ear secretions can initially generate an effusion, leading to obstruction and potential bacterial growth.[12] In adults, chronic otitis media is the most common primary disease. Its pathophysiology is the same as AOM and can result from upper respiratory infections or allergic rhinitis. Infections can also directly affect the auricle or ear canal in perichondritis or otitis externa, respectively. If the infection spreads to adjacent bone, it can cause petrous apicitis, mastoiditis, or malignant otitis externa.

Secondary or referred otalgia occurs as a result of the complex cranial nerve network that innervates the ear. These cranial nerves have a shared connection between the ear and organs outside of the ear. One theoretical mechanism of referred otalgia is the convergence-projection theory, which states that these nerves converge onto a shared neural pathway.[9] Given the extent of different organs that share innervation pathways with the ear, secondary otalgia can arise from many different organs.

History and Physical

A comprehensive history and physical examination are vital to evaluate otalgia. The clinician must consider both primary and secondary causes. History should include the following:

Red flags associated with otalgia include[4]:

- Dysphagia, odynophagia, dysphonia, or hemoptysis

- Loss of vision or black spots

- Unintended weight loss

Risk factors for a serious diagnosis, such as malignancy include [3][4]:

- History of smoking

- History of alcohol use (approximately 3.5 or more drinks per day)

- Immunosuppressed state, i.e., diabetes mellitus

Key features on history include:

- Shorter time-frames suggest more benign causes. Longer time-frames suggest a secondary cause.[4]

- Ear pain lasting over four weeks is more suspicious for malignancy, especially if in the presence of risk factors and normal otoscopy.[13][1]

- Ear fullness rather than ear pain may be more associated with cholesteatomas.

- Sharp, lancinating pain is more indicative of neuralgia or neuropathy.

- Malignancy tends to cause unilateral symptoms.[13]

- Ear pain exacerbated by swallowing is suggestive of glossopharyngeal neuralgia.[1]

- Of note, 1 case series noted "the otalgia point," located at the apex of the jugulodigastric region. The case series included 32 patients who pointed to this location, who also had normal physical examinations, tympanogram, and age-appropriate audiograms. This point was found to correlate more with symptom relief after either myringotomy or nasal steroid usage.[14]

The following associated symptoms could indicate the following referred origins:

- Sinus congestion - chronic rhinosinusitis

- Toothaches - dental pathology

- Hoarseness - vocal cord condition

- Heartburn - gastroesophageal reflux

- Chest pain - coronary artery disease

- Shortness of breath- lung disease

- Upper back pain - cervical disc disease or myofascial pain

- Headache, diplopia, malaise, jaw claudication, diplopia - temporal arteritis

It is also possible for patients to experience otalgia during the early postoperative phase of tonsillectomies.

Physical examination should include the following:

- Ear examination to identify signs of infection or other signs of primary etiologies. It may also reveal vesicular lesions, which can be found in herpes zoster oticus infection (Ramsay Hunt syndrome if it occurs with facial paralysis).

- Nasal examination to identify inflamed nasal mucosa or nasal polyps. It may reveal chronic rhinosinusitis.

- Oral cavity examination to identify dental caries, loose fillings, aphthous ulcers, abnormal growths, or abscesses. Intra-oral palpation may also detect an elongated styloid process, which can occur in Eagle syndrome.[15]

- Temporomandibular joint examination to identify temporalis, lateral/medial pterygoid, or masseter muscle tenderness. It may reveal trigger points or TMJ syndrome.

- Head examination to identify parotid or other salivary gland pathologies. It may reveal salivary gland tumors or sialadenitis. Tenderness along the temporal artery may reveal temporal arteritis.

- Neck examination to identify lymphadenopathy or thyroid gland pathology. It may reveal thyroiditis or lymph node malignancies.

- Cervical spine examination to identify cervical spine and related musculoskeletal exam pathology. It may reveal myofascial pain or cervical degenerative disc disease.

- Cranial nerve full examination to identify cranial nerve neuropathies. It may reveal trigeminal, glossopharyngeal, geniculate, sphenopalatine, occipital, vagal neuralgia, or Ramsay Hunt syndrome.[3][9]

- Cervical spine, cardiac, pulmonary, or abdominal physical examinations to identify referred pain from distant organ systems from the ear.

Evaluation

The first step in evaluating otalgia includes a comprehensive history and physical examination. Evaluation should exclude red flags and risk factors for a serious diagnosis. If found, then head & neck CT and MRI, panendoscopy, including nasolaryngoscopy and direct visualization of the upper aerodigestive tract, can be ordered. Gastrointestinal red flags should prompt a barium swallow or referral to gastroenterology for esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD). Chest pain and cardiac risk factors should prompt a full cardiac work-up. Clinical signs of temporal arteritis should prompt an ESR. An ESR greater than 50mm per hour indicates the need for an urgent referral to ophthalmology and otolaryngology.[3]

The next step should include an assessment of primary otalgia. Evaluation beyond a comprehensive history and physical examination is rarely necessary for primary otalgia. Acute otitis media is the most common cause of primary otalgia. Pneumo-otoscopy will reveal opacification, bulging, and immobility of the tympanic membrane. Eustachian tube dysfunction is another common cause of otalgia. A tympanometry will reveal abnormalities such as negative pressure within the middle ear. The Eustachian Tube Dysfunction Questionnaire (EDTQ-7) can also be an option in the primary care setting.[16] Audiometry could be a consideration if hearing loss is also present.

If the ear exam is normal and without an obvious cause of otalgia, then the next step is to perform a comprehensive evaluation for secondary causes. Clinical assessment should guide the need for lab or imaging studies. Dental and the temporomandibular joint are common sources of secondary or referred otalgia. Orthopantogram can provide a fast and easy way to give a panoramic view of the lower jaw and teeth. Imaging studies are not routinely required to evaluate temporomandibular joint disorder. CT imaging of the temporal bone may be used to assess for petrous apicitis. CT and MRI imaging can also evaluate malignant otitis externa. MRI of the cranial nerves can be ordered to evaluate cranial neuropathy. A complete blood count (CBC) can help screen for infection.

If the patient has not red flags, no risk factors for a serious diagnosis such as malignancy, no clinical signs of referred otalgia, then it is reasonable to trial non-steroidal analgesics such as ibuprofen or acetaminophen. If symptoms persist for over four weeks, then specialty referral and all of the above studies can be re-considered.[1]

Treatment / Management

Treatment of otalgia is dependent on the diagnosis. This section will review the salient points. Infections cause most primary otalgia and are treated with antibiotics, while mechanical receive treatment with decongestants, nasal steroids, or myringotomy. Secondary causes include a wide variety of diagnoses. One notable management point is the need for urgent referral and steroid treatment for temporal arteritis, a rare cause of secondary otalgia. Therapy otherwise addresses the underlying medical condition, such as malignancy, dental caries, temporomandibular joint disease, coronary artery disease, or gastroesophageal reflux. Patients who have an unremarkable clinical evaluation and no red flags or risk factors for serious disease can be treated conservatively with analgesics and re-evaluated in 4 weeks.

Differential Diagnosis

Primary Otalgia

Infectious causes:

- Acute or chronic otitis media

- Acute otitis externa

- Bullous otitis externa or myringitis

- Auricular perichondritis

- Herpes zoster oticus, Ramsay-Hunt syndrome

- Malignant otitis externa

Mechanical causes:

- Eustachian tube dysfunction

- Cerumen impaction

- Barotrauma

- Hematoma of Pinna

Neoplastic causes:

- Squamous cell carcinoma

- Basal cell carcinoma

- Melanoma

- Cholesteatoma

Inflammatory Causes:

- Chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis

- Wegener granulomatosis (with associated serous otitis media)

Secondary Otalgia

- Head: temporal arteritis

- Sinuses: sinusitis, nasal polyps

- Temporomandibular joint: temporomandibular joint disease, bruxism

- Temporal bone: petrous apicitis, Eagle syndrome (elongated styloid process)

- Salivary glands: sialadenitis (infection of salivary gland duct), sialolithiasis (salivary duct stones), salivary gland tumor

- Oral cavity: dental caries or other dental pathology, squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue

- Thyroid: thyroiditis, thyroid carcinoma

- Neck: carotidynia

- Lymph node: lymphadenopathy, lymph node malignancies

- Neuralgia: trigeminal, glossopharyngeal, geniculate, sphenopalatine, vagal, and occipital neuralgia [9]

- Pharynx: pharyngitis, oropharyngeal carcinoma, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, tonsillitis, post-tonsillectomy pain, peri-tonsilar abscess, tonsilloliths

- Larynx: laryngitis, vocal cord dysfunction, laryngeal carcinoma

- Musculoskeletal: myofascial pain, torticollis, cervical disc degeneration, cervical radiculopathy

- Lung disease

- Cardiac disease: myocardial infarction

- Gastrointestinal disease: gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), esophageal carcinoma

- Idiopathic or psychogenic

Prognosis

Both primary and secondary otalgia can arise from a wide variety of etiologies, each of which is treatable. Prognosis will depend on how early these diagnoses are made and, thus, relies on a comprehensive and systematic evaluation.

Complications

Complications from otalgia are also dependent on early diagnosis and treatment of the underlying cause. This section will review the salient points. Infections, if left untreated, can spread to the adjacent bone. This invasion can lead to more serious infections such as petrous apicitis, mastoiditis, or malignant otitis externa. Herpes zoster oticus is an otic viral infection. Ramsay Hunt Syndrome results if accompanied by facial nerve paralysis. Temporal arteritis is an auto-immune vasculitis, which can lead to blindness if not treated promptly.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Otalgia has many different causes. It divides into primary (arising from the ear) and secondary or referred (stemming from an organ outside the ear) causes. Primary otalgia tends to be more frequent and is usually due to an ear infection, acute otitis media, especially in children. Secondary otalgia can arise from locations close to the ear, such as the nose, sinuses, and neck. It can rarely occur from areas in the body that are more distant from the ear, such as in heart disease or gastroesophageal reflux. Evaluation and treatment largely depend on the diagnosis. It is essential to seek medical attention for ear pain, especially if associated with other symptoms.

Pearls and Other Issues

Primary Otalgia

- Most cases of primary otalgia in children are acute otitis media (AOM) in children ages six months to 24 months, peaking between 9 and 15 months. Watchful waiting for 24 to 72 hours is reasonable in non-toxic appearing children. The American Academy of Pediatrics has excellent guidelines on immediate treatment and delayed treatment[17].

- If AOM is associated with purulent conjunctivitis, use amoxicillin with clavulanic acid.[17]

- Breastfed infants in their first six months of life have lower rates of acute otitis media. This situation may be due to infant position and pressure differentials during feeding.[17]

Secondary Otalgia

- Secondary otalgia has an extensive differential diagnosis.

- Recall red flags and risk factors for serious diagnosis.

- Regular dental exams every six months to 1 year helps prevent dental pathology.

- One hundred fifty minutes of moderate-intensity exercise every week helps prevent cardiac pathology.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Primary otalgia is most commonly due to infection, which is routinely addressable in the primary care office. A referral is rarely needed, but a pharmacist can have involvement with antimicrobial therapy, checking for interactions, and verifying dosages. Secondary otalgia, however, will often require an inter-disciplinary care team. Temporomandibular joint disease may require coordination between the primary care physician, pain clinic, and a dentist. Dental pathology will require referral to a dentist. Chronic musculoskeletal conditions, such as cervical disc degeneration or trigger points, will require coordination of care with physical therapy and pain management. Malignancy will require consultation with an oncologist.

"The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the Department of the Army, Department of the Air Force, Department of Defense, or the U.S. government."