Papillary Muscle Rupture

- Article Author:

- Lauren Burton

- Article Editor:

- Kevin Beier

- Updated:

- 8/24/2020 11:18:27 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Papillary Muscle Rupture CME

- PubMed Link:

- Papillary Muscle Rupture

Introduction

Papillary muscle rupture is a rare and potentially fatal complication often following a myocardial infarction or secondary to infective endocarditis. Acute rupture frequently results in severe mitral valve regurgitation and subsequent acute life-threatening cardiogenic shock and pulmonary edema.[1][2][3][4]

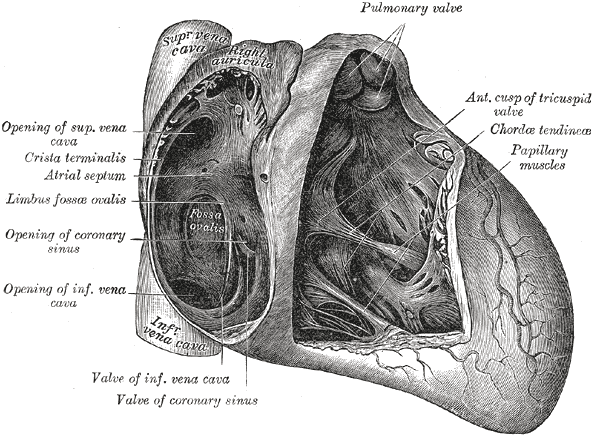

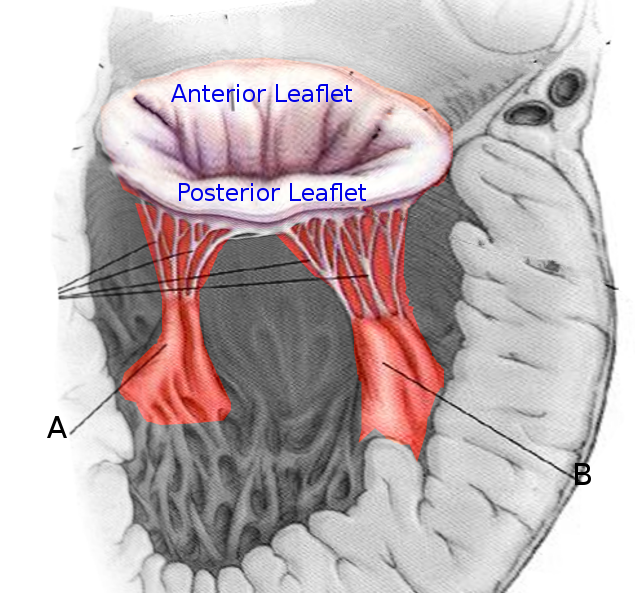

There are 5 papillary muscles in the heart originating from the ventricular walls. These muscles attach to the tricuspid and mitral valve leaflets via the chordae tendineae and functionally prevent regurgitation of ventricular blood via tensile strength by preventing prolapse or inversion of the valves during systole. Three of these papillary muscle and chordae tendineae complexes are attached to the tricuspid valve (anterior, posterior, septal), and 2 are attached to the mitral valve (anterolateral and posteromedial). Papillary muscle dysfunction leads to regurgitation of blood through the valves causing backflow of blood that can lead to left or right-sided heart failure.

Literature first identified papillary muscle rupture as early as 1948. Visualization via 2-dimensional echocardiography was first reported in 1981. Transesophageal echocardiography was first used in 1985 in identifying the condition.[5][6][7]

The classic scenario is that of a patient with an MI involving the posterior descending coronary artery who develop sudden decompensated heart failure on days 2-7 after the infarction. The competence of the mitral valve is maintained by the actions of the anterolateral and posteromedial papillary muscles. The anterolateral muscle has a dual blood supply, whereas the posteromedial muscle has blood supply only from the posterior descending coronary; thus in most patients, it is the posteromedial papillary muscle that will rupture following an MI.

Without surgical treatment, mortality is very high.

Etiology

The most common cause of papillary muscle rupture is secondary to myocardial infarction. This usually occurs 2 to 7 days post-ischemic event. Rupture occurs more commonly with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarctions, but also occur less frequently with non-ST segment elevation infarctions. Other possible documented etiologies of rupture include trauma, syphilis, periarteritis nodosa, vegetating valvulitis, myocardial abscess, iatrogenic, and cocaine use.

Epidemiology

Papillary muscle rupture is rare, estimated to occur in 1% to 5% of patients with acute myocardial infarctions. This is thought to be due to improvements in early identification and early revascularization techniques via percutaneous coronary interventions to limit ischemia. When rupture does occur, there is high mortality without surgical intervention, estimated to be as high as 50% within 24 hours with complete rupture. Prior to the initiation of cardiac surgical procedures to repair injuries, mortality was estimated to be 80% to 90% within the first 24 hours. One study found that 82% of post-infarct papillary muscle ruptures occurred in patients with their first myocardial infarction.[8][9]

Pathophysiology

Rupture of the papillary muscle can be both partial and complete. Partial rupture (occurring at one of the muscle heads) cause fewer leaflets to flail and has less valvular regurgitation. These are hemodynamically better tolerated than a complete rupture. Partial rupture has been documented to occur up to 3 months after infarction. Complete rupture of the papillary trunk, which usually occurs within 1-week post-infarction, leads to rapid clinical deterioration. Classically, the posteromedial papillary muscle is the most commonly injured due to its single blood supply from the posterior descending coronary artery (the right coronary artery is the most often involved causing inferior wall ischemia, followed by the left circumflex artery) versus the dual blood supply that delivers to the anterolateral papillary muscle. Posteromedial muscle rupture is 6 to 12 times more common than the anterolateral. About 50% of patients have single-vessel disease. Most cases of documented papillary muscle rupture demonstrate small areas of ischemia (usually less than 25% of the ventricle) with poor collaterals. The etiology of papillary muscle rupture in small infarcts is thought to be due to preserved ventricular function resulting in a high shear force on the ischemic papillary muscle.

History and Physical

Suspicion of papillary muscle rupture should be considered in patients following the first week after myocardial infarction with sudden acute heart failure symptoms. A high level of suspicion should be contemplated in those with their first myocardial infarction that involves the inferior wall. Rapid, severe regurgitation from papillary muscle failure causes atrial dilatation secondary to an abrupt increase in atrial pressure. This coupled with a hyperactive precordium, and insufficient turbulence of blood through the regurgitant valve makes diagnosis clinically difficult at times because, often, there is not a stethoscopically audible regurgitant murmur. This is due to the equalization of pressures between the atria and ventricle. Patients who do have murmurs can have mid, late, or holosystolic murmurs. Symptoms and physical findings are determined by the valve affected. The most papillary muscle chordae tendineae complex affected is the posterior-medial papillary muscle of the mitral valve involved, and thus acute left-sided heart failure symptoms are found which include rapidly progressive pulmonary edema and hypoxia. Cardiogenic shock with hypotension is also commonly observed. Chest pain has also been cited as a symptom in some patients. Given the swift onset of cardiogenic shock and catastrophic complications, prompt identification is important given the rise in mortality rates without emergency surgical intervention.

Evaluation

Identification of papillary muscle rupture and acute valvular insufficiency may be demonstrated by transthoracic (TTE) or transesophageal echocardiography (TEE). Transthoracic echocardiography may demonstrate a flail mitral valve leaflet with prolapse during systole into the atrium, visualization of a ruptured papillary muscle head with erratic movements in the ventricle or a mobile mass attached to the chordae tendinea. The sensitivity of TTE to visualize the structural abnormalities has been reported between 65-85%. It is recommended to utilized transesophageal echocardiography with unequivocal TTE results, as TEE sensitivity has been reported as high as 92-100%.

Many of these patients are too hemodynamically unstable to undergo invasive procedures, and thus TTE is typically the initial diagnostic method used. Doppler echocardiography and color flow imaging is also a helpful aid in identifying the severity of the regurgitant jet across the valve. Use of echocardiography is superior to cardiac catheterization as the muscle rupture can be diagnosed with minimal risk to the patient. In addition to acute valvular surgery, coronary revascularization is strongly suggested, and those patients receiving such have demonstrated improved mortality rates.

Treatment / Management

The cornerstone of treatment for papillary muscle rupture includes emergency surgical treatment. Initial medical therapy can be instituted with diuretics, afterload reduction and oxygen therapy (bilevel positive airway pressure or mechanical ventilation may be necessary). Intra-aortic balloon counter-pulsation may be necessary for severely unstable patients. Previous intraoperative mortality associated with mitral valve repair in these patients was estimated to be 20% to 25%. More recently, a study from 2008 identified a decrease in operative mortality from mitral surgery (previous overall mortality of 18.5%) to be decreased to 8.7% when associated with coronary artery bypass grafting. However, the small sizes in these studies analyzing the surgical effectiveness of treating papillary muscle rupture leave this a controversial topic.

Another treatment controversy is whether mitral valve repair is more beneficial than valve replacement. At the time of this writing, repair over replacement is currently preferred unless necrotic papillary muscle tissue is present.

Concomitant coronary artery bypass has been shown to improve outcomes and should be done.

Suboptimal outcomes following valve repair have been linked to prolonged cross-clamp times, suturing into friable necrotic tissue and tissue remodeling after infarction. Partial papillary muscle rupture may be delayed by surgeons up to 6 to 8 weeks post-infarction to allow for necrotic tissue to resolve. This depends on the stability of the patient and may need to be surgically corrected sooner.

Differential Diagnosis

Other complications that may present with similar presentations include cardiogenic shock due to severe left and right ventricular dysfunction, ventricular septal rupture, and free-wall myocardial rupture. These are all post-myocardial infarction complications. Severe left ventricular dysfunction presented with pulmonary edema and decreased cardiac output leading to organ hypoperfusion. Severe right ventricular dysfunction presents with elevated jugular venous pressure, peripheral edema, hypotension, and clear lung fields. Right ventricular failure can also result in the underfilling of the left heart chambers that results in a low cardiac output state. Ventricular septal rupture has a 5% mortality rate and can be seen with anterior infarction, unlike papillary muscle rupture which is rarely seen in anterior cardiac ischemia.

Septal rupture occurs where necrotic tissue is located and creates a left-to-right shunt and new pansystolic murmur. Rapid pulmonary edema is typically not seen. Free-wall myocardial rupture is similar to septal rupture and papillary muscle rupture, in that small infarctions and single-vessel disease are often the etiologies. Left ventricular wall rupture is the most common site and occurs within five days in 50% of patients and within 2 weeks in 90% of patients. Survival depends on whether the rupture is complete or subacute with a high fatality rate (essentially 100%) in complete ruptures as this leads to abrupt onset cardiac tamponade.

Prognosis

One study evaluating 22 patients reported a perioperative mortality rate of 27% and overall survival of 47% at 7 years. Another study of 55 patients demonstrated an overall operative mortality rate of 24% with a higher mortality rate in patients who did not undergo coronary revascularization (39% versus 9%). Finally, in the third study of 54 patients, a 10-year survival rate was reported as 35%, and 10-year congestive heart failure-free rate was 23%.

Complications

- Cardiogenic shock

- Death

Consultations

Immediate cardiology and cardiothoracic surgery consults are indicated in cases of suspected papillary muscle or chordae tendineae rupture.

Pearls and Other Issues

Acute papillary muscle or chordae rupture and secondary acute valvular regurgitation should be considered in any patient presenting with acute pulmonary edema or shock, especially in the days following acute myocardial infarctions. These patients are highly unstable, and urgent cardiology and cardiovascular surgery consults are indicated. Mortality can be substantially reduced with rapid identification and referral for valvular repair or replacement and revascularization. The best initial study for identification in an unstable patient is transthoracic echocardiography, while transesophageal echocardiography is reserved for those with equivocal TTE studies.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Patients with a myocardial infarction are ideally managed by an interprofessional team that includes cardiology nurses. When papillary muscle is diagnosed, the patient must be prepared for immediate surgery. The only difficulty is the decision to perform a cardiac catheterization in an unstable patient. Some surgeons take the patient to the operating room without a cardiac catheterization assuming that the RCA/PDA is already involved. Because of the extremely high mortality following papillary muscle rupture, the focus today is on the prevention of coronary artery disease. The cardiology nurse, pharmacist and primary clinicians should educate the patients on the following:

- Participate in regular exercise

- Eat a healthy diet

- Remain in compliance with medications

- Abstain from alcohol

- Discontinue smoking

- Take statins as prescribed

- Maintain a healthy body weight

- Monitor and maintain normal blood pressure and blood glucose

Patients with risks for coronary artery disease must be closely followed and referred to a cardiologist for definitive care. Close communication between the team members is vital if one wants to improve outcomes. The outcomes for these patients are guarded. Without surgery, the disorder is fatal; even with surgery, recovery is slow.

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)