Paracentesis

- Article Author:

- Elisa Aponte

- Article Author:

- Shravan Katta

- Article Editor:

- Maria O'Rourke

- Updated:

- 9/9/2020 9:25:39 AM

- For CME on this topic:

- Paracentesis CME

- PubMed Link:

- Paracentesis

Introduction

Paracentesis is a procedure performed to obtain a small sample of or drain ascitic fluid for both diagnostic or therapeutic purposes.[1][2][3] A needle or catheter is inserted into the peritoneal cavity and ascitic fluid is removed for diagnostic or therapeutic purposes. The fluid may be used to determine the etiology of ascites and evaluate for cancer or infection.

Anatomy and Physiology

Paracentesis is done in a lateral decubitus or supine position. The ascites fluid level is percussed, and a needle is inserted either in the midline or lateral lower quadrant (lateral to rectus abdominis muscle, 2 cm to 4 cm superomedial to anterior superior iliac spine).[1][2]

- This positioning avoids puncture of the inferior epigastric arteries

- Avoid visible superficial veins and surgical scars

The needle is inserted at a 45-degree angle or with a z-tracking technique to reduce the risk of developing an ascites fluid leak.

Indications

Paracentesis should be performed to:

- Rule out spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in patients with known ascites presenting with concerning symptoms such as abdominal pain, fever, gastrointestinal bleed, worsening encephalopathy, new or worsening renal or liver failure, hypotension, or other symptoms of infection or sepsis

- Identify the etiology of new-onset ascites

- Alleviate abdominal discomfort or respiratory distress in hemodynamically stable patients with tense ascites or ascites that are refractory to diuretics (large volume therapeutic paracentesis)[1][2]

Contraindications

There are few absolute contraindications for paracentesis.[3] Coagulopathy and thrombocytopenia (both very common in cirrhotic patients) are themselves not absolute contraindications as the incidence of bleeding complications from the procedure has been shown to be very low.[4] Paracentesis should be avoided in patients with:

- DIC (consider first administering platelets or FFP)

- An acute abdomen

It should be performed with caution in:

- Pregnant patients

- Patients with organomegaly, ileus, bowel obstruction or a distended bladder

Avoid passing the needle/catheter through sites of skin infection, surgical scars, visibly engorged abdominal wall vessels or abdominal wall hematomas.

Equipment

Prepackaged paracentesis kits with plastic sheath cannulas attached to a syringe and a stopcock are available. Alternatively, traditional large-bore intravenous (IV) catheters or 18 gauge to 20 gauge standard or spinal needles can be used. These can be attached to a syringe for aspiration and then to IV tubing for fluid drainage. If you do not have a pre-packaged kit, you will need the following:

- sterile gloves

- sterile drapes/towels

- chlorhexidine or betadine

- 1% lidocaine, a needle to inject anesthetic (25 gauge for the skin and a slightly smaller gauge needle for the soft tissue)

- a 14 or 16 gauge needle or IV catheter for fluid aspiration (spinal needle for obese patients)

- a 20 cc or 60 cc syringe to collect a sample of fluid

- IV tubing

- vacuum bottles or plastic canisters (if performing large volume paracentesis)

- 4x4 gauze or bandage

- hematology, chemistry and microbiology sample tubes and blood culture bottles [3]

Preparation

The preferred site for the procedure is in either lower quadrant of the abdomen lateral to the rectus sheath. Placing the patient in the lateral decubitus position can aid in identifying fluid pockets in patients with lower fluid volumes. Ask the patient to empty his or her bladder before starting the procedure.

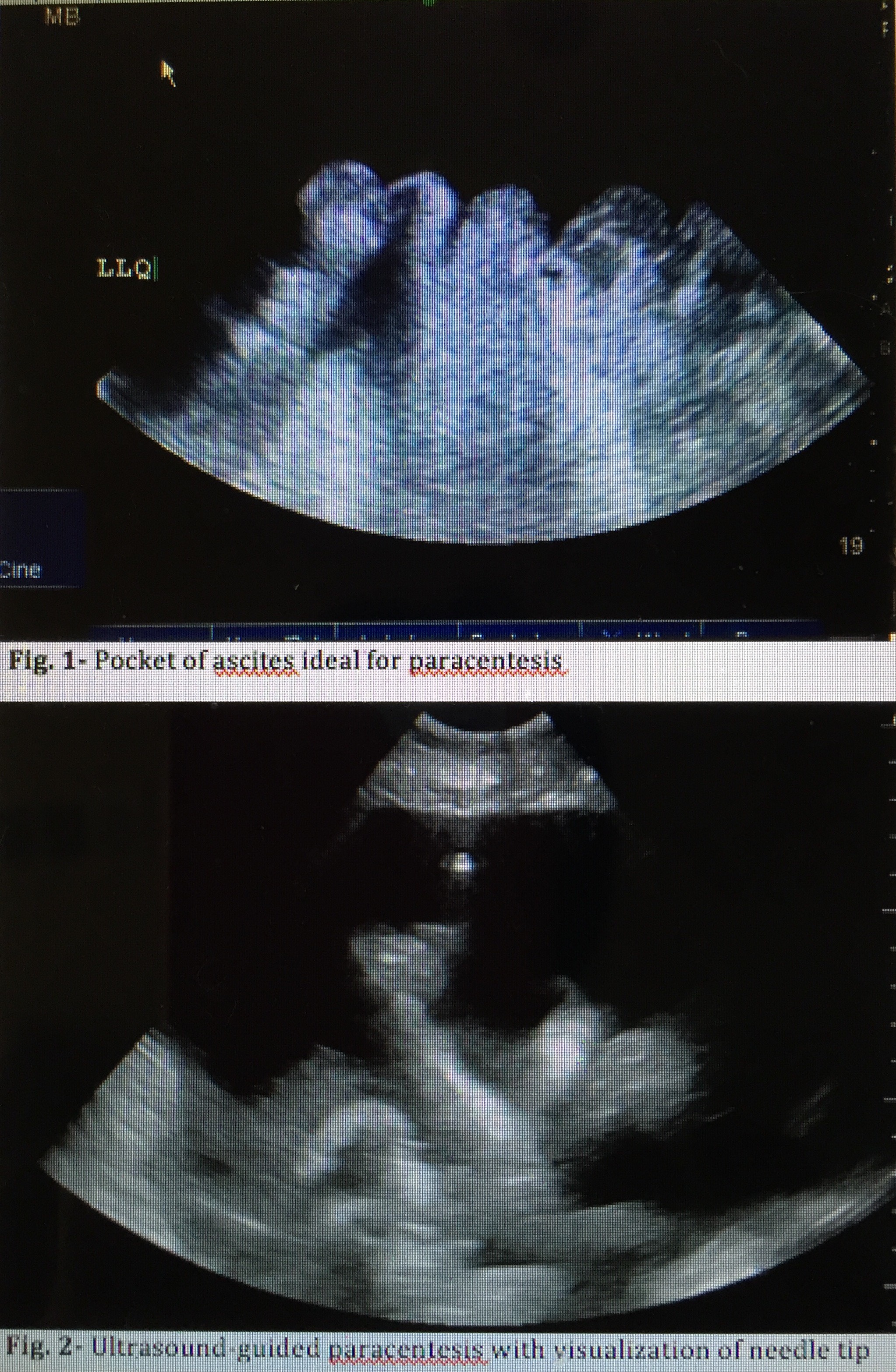

Bedside ultrasound should be used to identify an appropriate location for the procedure. Ultrasound can confirm the presence of fluid (Fig. 1) and identify an area with a sufficient amount of fluid for aspiration, thereby decreasing the incidence of both unsuccessful aspiration and complications. Ultrasound increases the success rate of paracentesis and helps to prevent an unnecessary invasive procedure in some patients.[5]The procedure can be performed either after marking the site of insertion or in real time by advancing the needle under direct ultrasound guidance (Fig. 2).

Technique

Prep and drape the patient in a sterile fashion. Cleanse the skin with an antiseptic solution. Administer local anesthesia to the skin and soft tissue (down to peritoneum) at the planned site of needle or catheter insertion. Insert the traditional needle or IV catheter attached to a syringe or the prepackaged catheter directly perpendicular to the skin or using the z-track method which is thought to decrease the chance of fluid leakage after the procedure. This method entails puncturing the skin then pulling it caudally before advancing the needle through the soft tissue and peritoneum. If using a catheter kit, it may be helpful to make a small nick in the skin using an 11-blade scalpel to be able to advance the catheter through the skin and soft tissue smoothly. Apply negative pressure to the syringe during needle or catheter insertion until a loss of resistance is felt and a steady flow of ascitic fluid is obtained. This is paramount to detect unwanted entry into a vessel or other structure rapidly. Advance the catheter over the needle into the peritoneal cavity. After you collect sufficient fluid in the syringe for fluid analysis, either remove the traditional needle (if performing a diagnostic tap) or connect the collecting tubing to it or the catheter's stopcock to drain larger volumes of fluid into a vacuum container, plastic canister, or a drainage bag. After you have drained the desired amount of fluid, remove the catheter, and hold pressure to stop any bleeding from the insertion site.[1][3]

Peritoneal Fluid Analysis

Send ascitic fluid for laboratory testing including cell count with differential, Gram stain, and fluid culture. Placing some fluid into bacterial culture bottles can help to increase culture sensitivity.[2] Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis is diagnosed when the absolute neutrophil count (PMN) is 250 cells/mm3 or more.[2][3] This is calculated by multiplying the number of white cells by the percentage of neutrophils reported in the differential. Empiric antibiotics, typically a third-generation cephalosporin or a fluoroquinolone, should be started in patients with ascites and a high suspicion for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis regardless of the absolute neutrophil count or in patients with an absolute neutrophil count above the cut-off range. Additional tests that can aid in inpatient management include albumin, total protein, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), glucose, cytology, and tumor markers. Albumin, in particular, can be used to calculate the serum-ascites albumin gradient (SAAG) which can assist in determining the etiology of ascites by classifying it as either exudative or transudative. Serum Ascitic Albumin gradient (SAAG) is useful in identifying the presence of portal hypertension. SAAG is calculated by subtracting the ascitic fluid albumin from the serum albumin obtained on the same day. SAAG greater than 1.1, indicates the high probability of portal hypertension. SAAG less than 1.1 rules out portal hypertension[2][6]

Complications

Paracentesis is a safe procedure [7], however possible complications include:

- Persistent leakage of ascitic fluid at the needle insertion site. This can often be addressed with a single skin suture.

- Abdominal wall hematoma or other bleeding

- Infection

- Perforation of surrounding vessels or viscera (extremely rare)

- Hypotension after large volume fluid removal (more than 5 L to 6 L). Albumin is often administered after removal of more than 5 L of fluid to prevent this complication.[3][8]

Clinical Significance

Development of fluid in the peritoneal space or ascites can occur as a result of many different disease states. Performing a paracentesis will help determine the etiology of a patient's ascites. Draining the peritoneal fluid may help identify infection, causes of liver disease or portal hypertension and also relieve symptoms by removing a large volume of fluid. Using bedside ultrasound to identify an ideal pocket of fluid will increase the likelihood of a successful procedure.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Paracentesis is a relatively simple procedure performed at the bedside. The procedure is often performed by the internist, emergency department physician, radiologist, general surgeon or the intensivist. These patients need close monitoring by the nurses as the procedure can be associated with hypotension, bleeding and leakage of fluid. When done for therapeutic reasons, it can quickly relieve symptoms. However, in many cases recurrence of ascites is common and adversely affects the quality of life. [9][10]