Paraganglioma

- Article Author:

- Asad Ikram

- Article Editor:

- Anis Rehman

- Updated:

- 6/30/2020 12:19:59 AM

- For CME on this topic:

- Paraganglioma CME

- PubMed Link:

- Paraganglioma

Introduction

Paragangliomas are rare, catecholamine (norepinephrine) secreting neuroendocrine tumors commonly located in pre-aortic and paravertebral sympathetic plexus or skull base. Head-and-neck paragangliomas in the jugular foramen, ear, or carotid body are less differentiated tumors. They secrete norepinephrine as compared to more differentiated intraabdominal adrenal medulla tumors like neuroblastoma and pheochromocytoma (also called intra-adrenal paragangliomas, which primarily secrete epinephrine).[1] Glomus jugulare and carotid body paragangliomas comprise 80% of paragangliomas in the head-and-neck. Functionally, pheochromocytomas/paragangliomas are highly vascular and may be either parasympathetic or sympathetic.

The parasympathetic tumors are usually asymptomatic and inactive, located mostly in the skull base in the distribution of IX and X cranial nerves. In contrast, sympathetic lesions are highly active and symptomatic and mainly located in the abdomen and pelvic regions. They are more functional and hypersecretory (norepinephrine) than the skull base paragangliomas. Paragangliomas are commonly a single unilateral tumor, but 1% vs. 20 to 80% may be multiple in sporadic vs. familial types, respectively.[2] They are usually benign tumors, and a small percentage may become malignant and metastasize. Hence, an early identification leading to complete surgical resection is often curative and carries a favorable prognosis. Detecting distant metastases is the only reliable way to assess the biological aggressiveness of paragangliomas. They are mostly sporadic, but 30 to 40% are familial, and some of those may be associated with genetic syndromes like succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) / B-mutations, Carney-stratakis dyad, neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), Von Hippel Lindau (VHL), and multiple endocrine neoplasia types 2A and 2B (MEN2).[3] Surgical biopsy of the lesion is the gold standard to confirm the diagnosis, but it does not differentiate between pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. Clinical correlation is usually enough for the diagnosis aided by imaging and pathology findings of the lesion.

Etiology

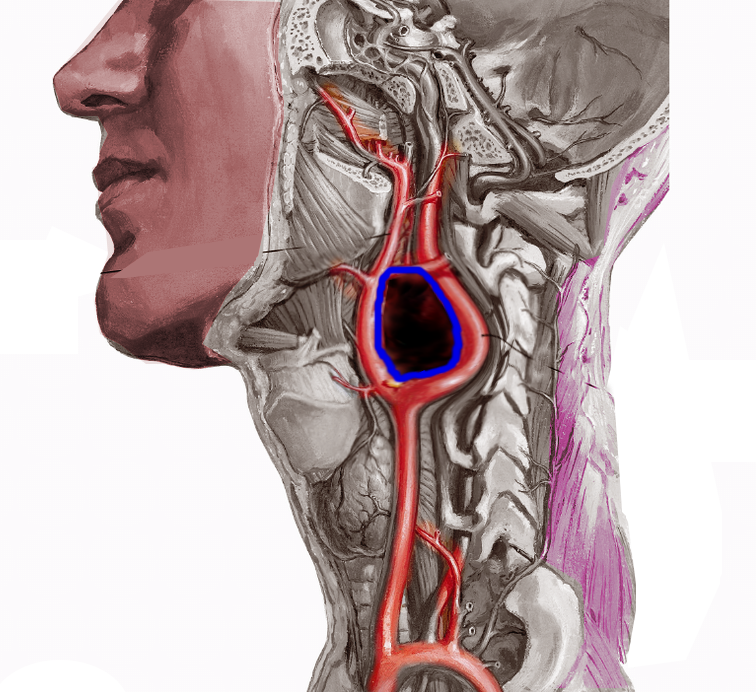

Paragangliomas are a rare type of catecholamine secreting neuroendocrine tumors or neoplasms that originate during the neural crest cell migration.[4] Their name usually coincides with the location of the tumor: carotid body lesion located at the carotid bifurcation, glomus tympanicum occurs in the middle ear but does not involve jugular foramen, jugulotympanic paraganglioma (previously called glomus jugulotympanicum) appears in the middle ear cavity and superolateral area of jugular foramen, glomus vagale located in the posterolateral pharynx, laryngeal paraganglioma in laryngeal area. The only exception is chemodectoma (carotid and aortic body) due to chemoreceptor function. Parasympathetic paragangliomas are also called non-chromaffin tumors in contrast to metameric (chromaffin-secreting) sympathetic paragangliomas.[5]

Parasympathetic paragangliomas located in the skull base are usually non-secretory, and less than 5% secrete catecholamines and may become symptomatic. Sympathetic paragangliomas mainly secrete norepinephrine and may arise anywhere from the skull base, along the sympathetic chain to the pelvis, primarily located in the abdomen nearly 75 to 80% of all paragangliomas and always secrete norepinephrine causing symptoms similar to that caused by pheochromocytoma. A small percentage of 5 to 10% may present in the bladder or prostate.[6] Conversely, pheochromocytomas may occur in the adrenal gland or at extra-adrenal sites, which is usually the superior para-aortic region between the diaphragm and kidneys.

Glomus jugulotympanicum paraganglioma is usually a single tumor that appears sporadically, but it rarely arises by familial autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. It typically appears in the 60s, and it may involve cranial nerves (CN) IX, X, XI, and XII and cause paralysis in the affected nerve distribution. Prognosis is poor and may require embolization, surgical removal, and radiotherapy. Jugular-tympanic paragangliomas can be diagnosed early due to classic symptoms of pulsatile tinnitus with or without conductive hearing loss. Glomus vagale is the rare but most common solitary tumor of post-styloid parapharyngeal space (PPS) causes hoarseness and mass effect due to vocal cord paralysis. It pushes the internal jugular vein posterolaterally and the internal carotid artery anteromedially. CT scan and MRI are very sensitive for the diagnosis due to the increased vascularity of this tumor. Treatment is usually surgical resection but carries a high risk of deficits in the tenth cranial nerve distribution. Carotid body mass is generally located at the carotid bifurcation and displaces the external carotid artery anteromedially and internal carotid artery posterolaterally.

Epidemiology

There are 500 to 1000 cases diagnosed per year in the United States. Although incidence in the US is not precisely known but, combined benign paraganglioma/pheochromocytoma incidence is roughly estimated 0.7 to 1.0 per 100000 person-years.[7] Comparatively, malignant paragangliomas have 90 to 95 occurrences per 400 million person-years. Sporadic paraganglioma is usually diagnosed during the third through fifth decades of life and is more common in women with the female to male ratio of 3 to 1, as compared to hereditary type, which is diagnosed earlier in the patients' thirties with the male to female ratio of 1 to 1.[7][8]

Pathophysiology

Pathogenesis is due to the sympathetic discharge of catecholamine (mainly norepinephrine) or direct mass effect. This activity discusses detailed signs and symptoms later, but a brief outline of systemic pathogenesis and manifestations due to catecholamine secretion are as follows:

- Gastrointestinal Manifestations: chronic constipation is the most common GI symptom, dry mouth is also a prevalent manifestation of sympathetic discharge and dysphagia can be seen in aortic sinus tumor or paraaortic tumors and mostly due to the mass effect.

- Cardiovascular Manifestations: These include chest pain, tachycardia, diaphoresis, episodic syncope, and paroxysmal hypertension are common manifestations.[9]

- Neurologic Manifestations: hoarseness, cranial nerve paralysis due to direct involvement or mass effect, and dilated pupils are noticeable.

- Endocrine Manifestations: polyuria and polydipsia can be present in certain cases.

- Psychiatric Manifestations: panic symptoms, fidgetiness may commonly present, mostly due to chemical imbalance and cardiac symptoms.

- Musculoskeletal Manifestations: generalized fatigue is very common and is usually due to the exhaustion.

- Urologic Manifestations: micturition syncope can occur in some cases.

Histopathology

Histologically, paragangliomas and pheochromocytoma are almost identical, arise from chromaffin cells. Both sympathetic and parasympathetic paraganglioma are indistinguishable on the cellular level.[5] The gross specimen is firm, rubbery, brown with a central scar with or without a pseudo-capsule. Microscopically, irregular clusters of irregular nuclei are present with a remarkable trabecular pattern or Zellballen (nesting) cells within a highly vascular tissue where anastomosing bands may obscure the nesting cells. Giant multinucleated cells with basophilic or abundant granular eosinophilic cytoplasm or round, oval cells are visible. Sympathetic cells may have hyaline globules in h&e stain, and giant mitochondria with paracrystalline inclusions may be noticeable on electron microscopy. Finally, Nuclear atypia, pleomorphism, necrosis, mitotic figures, and local/vascular invasion is common but not indicative of malignancy. Distant metastasis is the only indicator of malignancy.[10]

History and Physical

Paragangliomas are very hypervascular tumors and mostly benign and slow-growing. These tumors are often very symptomatic, and may cause fight-or-flight sympathetic symptoms like dry mouth, flushing of the face, racing heart, dilated pupils, fidgetiness, constipation, fatigue, profuse sweating, headache, tremors, panic-like symptoms and generalized weakness due to exhaustion. It may also present with blurry vision, lightheadedness, weight loss, excessive thirst or hunger, mood disturbances, high blood sugar, and weight loss.[11] However, the most classical presentation has the triad of headache, palpitations, and profuse sweating.[8]

Examination usually reveals signs of sympathetic overload or mass effect, including but not limited to vocal cord paralysis causing hoarseness, cranial nerve paralysis, fidgety, tachycardia, diaphoresis, uncontrolled episodic hypertension (more common in pheochromocytoma than other paragangliomas), perspiration; cold/clammy skin, dilated eyes, dry mouth, and sometimes piloerection could be noticeable. Signs and symptoms like bradycardia and syncope due to carotid sinus syndrome or hemoptysis, dysphagia, or chest pain in superior venous sinus syndrome may occur.

Evaluation

Blood and Urine Tests: The first step in the diagnosis of pheochromocytoma and/or paraganglioma is to validate the excessive production of catecholamines and then followed by anatomical identification of the tumor. The measurement of plasma fractionated metanephrines is usually the first screening test as it has a high sensitivity of 97% and an acceptable specificity of 93%.[12] Meanwhile, checking plasma catecholamine is less sensitive; however, if it shows as elevated more than twice the normal upper limit of the test, it can also be diagnostic.[8] A test for the 24 hr urine catecholamine, as well as the 24 hr urine metanephrines, are very helpful in making the diagnosis. It is important to understand certain medications such as tricyclic antidepressants, serotonin-reuptake, or norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, antipsychotics, and levodopa can result in a false-positive test. Hence, the results require confirmation once the patient has been taken off from these medications for at least two weeks. Moreover, stressful clinical conditions, i.e., acute illness, can also contribute to false-positive test results.[8] Head and neck paragangliomas can present as carotid body tumors without catecholamine secretion.

Radiological Tests: Upon obtaining proof of excessive catecholamines production, imaging modalities are the next step. Computed tomography (CT) scanning or T2 weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the entire retroperitoneum rather than the thorax or pelvis should be then be used to locate the tumor. CT scans should be non-contrast. If the CT shows 10 Hounsfield units or less, it suggests a lipid-rich mass and hence rules out pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. If the tumors are still not localized, the next step should be functional imaging. MRI shows the typical salt-and-pepper appearance of the tumor: salt-appearance is rare that reflects 'hemorrhage' and pepper is due to 'flow voids' shows high vascularity.

Functional Tests: 123-I meta-iodo-benzyl-guanidine (MIBG) or positron-emission tomography with Galium labeled 1,4,7,10-tetra-acetic acid-octreotate (Ga DOTATATE-PET-CT) or F-labeled L-dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-DOPA) are extremely sensitive in identifying any hidden pheochromocytoma and/or paraganglioma. Ga-DOTATATE PET-CT has limited availability; however, in difficult cases, it is the most accurate test to locate a tumor.[13]

Genetic Tests: Mutations such as SDHA, SDHD, SDHB, Carney-stratakis dyad, RET, NF1, VHL, MAX, TMEM127, and MEN 2A, and 2B, have been associated with pheochromocytoma and/or paraganglioma. Patients are offered genetic testings once the diagnosis and treatment have concluded.[8]

Surgical Biopsy: Lesional biopsy is the gold standard to confirm the diagnosis but does not differentiate between pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. Since most paragangliomas are vascular, a preoperative biopsy is not common.

Treatment / Management

Surgical resection is the first-line treatment for paraganglioma and pheochromocytoma. Based on tumor behavior, it may be necessary to control blood pressure before the surgery as well as to prevent an intraoperative hypertensive crisis.[8]

Differential Diagnosis

Following is the list of possible differential diagnoses based on tumor characteristics [5]:

- Pheochromocytoma

- Hyperadrenergic spells

- Syncope

- Thyrotoxicosis

- Pancreatic tumors (e.g., insulinoma)

- Hypoglycemia

- Hyperventilation

- Labile essential hypertension

- Sympathomimetic drug ingestion

- Diencephalic epilepsy (autonomic seizures)

- Mast cell disease

- Somatization disorder

- Paroxysmal cardiac arrhythmia

- Carcinoid syndrome

- Recurrent idiopathic anaphylaxis

- Renovascular disease

- Anxiety and panic attacks

- Factitious (e.g., drugs, Valsalva)

- Illicit drug ingestion

- Vancomycin related red man syndrome)

- Autonomic neuropathy

- Migraine headache

- Stroke

- Unexplained flushing spells

Surgical Oncology

Surgical resection with open laparotomy was the standard of care till 1996 when endoscopic removal of pheochromocytoma first took place. In the current era, endoscopic techniques are preferable due to fewer intraoperative and postoperative complications. Preoperative preparation is the key to prevent intraoperative complications. It is recommended to start antihypertensive medications at least seven days before surgery with the target goal to have low-normal blood pressure.[8]

Moreover, the overall hospital length of stay is much shorter. In retroperitoneal areas, when the tumors are present in pelvic para-vesicular or thoracic paravertebral regions, minimally invasive surgeries are performed based on the location of the tumor.[14] Head-and-neck paragangliomas are challenging and need an individualized approach with surgical resection, stereotactic radiosurgery, or external beam radiation treatment.

Prognosis

Prognosis of solitary paraganglioma is usually reassuring if the tumor is not located in a sensitive area and can have safe resection without injury to delicate surrounding structures. Malignant tumors are very rare and usually have a poor prognosis. Yearly follow-up serum or urine fractional metanephrines are advisable. There is a small risk of recurrence of paragangliomas.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Postoperative rehabilitation care may be necessary after surgery based on tumor location and post-surgical deficits. Since most of the patients undergo endoscopic tumor resection, post-op rehabilitation care needs are minimal, as well as the shortened length of stay in the facility.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Paragangliomas have a diverse presentation, and their diagnosis can be difficult. Because they can occur anywhere in the body, management optimally employs an interprofessional team.

If anytime paragangliomas are suspected, an endocrinologist should be taken on board to complete the biochemical work up as well as localization of the tumor with radiological imaging or functional testing. Then the patient requires a referral to a specialized surgeon based on the location of the tumor and type of surgery. Some tumors like a pheochromocytoma need meticulous blood pressure management prior to surgery, and hence, the pharmacist should be involved. The patient should be educated about medication compliance to prevent malignant hypertension, which will enlist the services of an oncology specialty-trained nurse. These nurses are also invaluable before, during, and following the surgery, for preparation, assisting, and postoperative monitoring. Following surgery, nurses should carefully monitor the autonomic parameters like heart rate, blood pressure, temperature, diaphoresis, and fluid balance, and inform the oncologist/surgeon of any issues that arise. Open communication between interprofessional team members is vital to improving patient outcomes. [Level 5]