Anatomy, Head and Neck, Nose Paranasal Sinuses

- Article Author:

- Zachary Cappello

- Article Author:

- Katrina Minutello

- Article Editor:

- Arthur Dublin

- Updated:

- 9/20/2020 9:06:18 AM

- For CME on this topic:

- Anatomy, Head and Neck, Nose Paranasal Sinuses CME

- PubMed Link:

- Anatomy, Head and Neck, Nose Paranasal Sinuses

Introduction

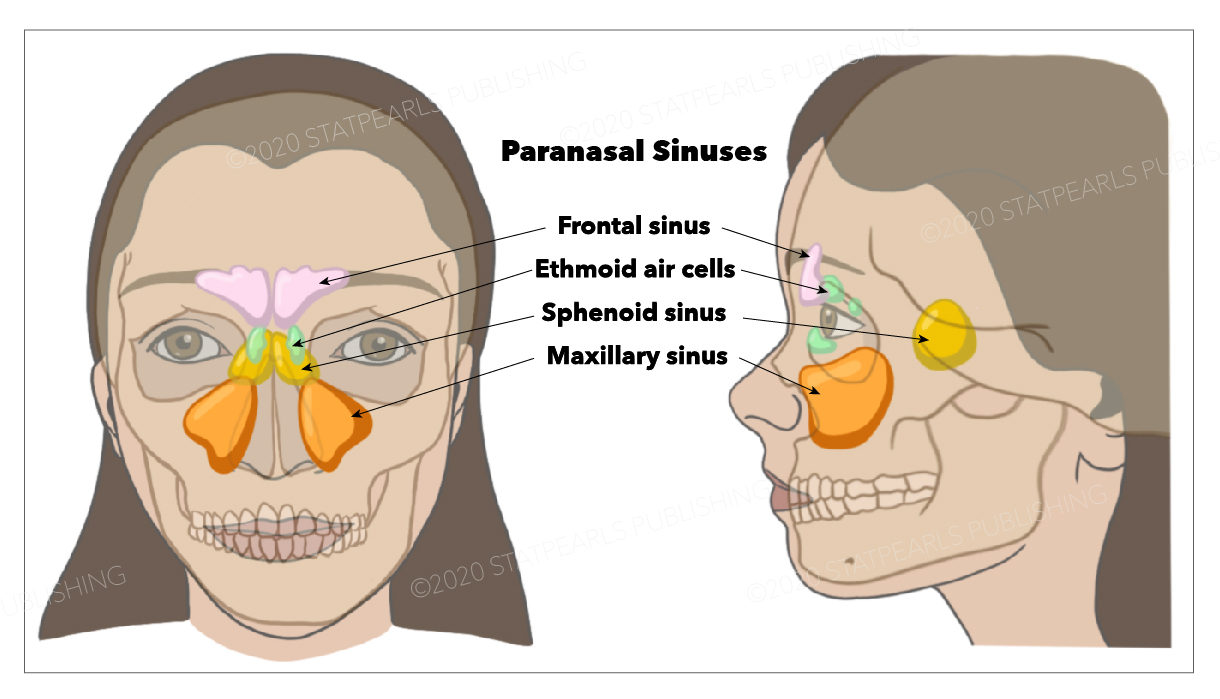

The nasal cavity is a roughly cylindrical, midline, airway passage that extends from the nasal ala anteriorly to the choana posteriorly. It is divided in the midline by the nasal septum. On each side, it is flanked by the maxillary sinuses, and roofed by the frontal, ethmoid, and sphenoid sinuses, in an anterior to posterior fashion. While seemingly simple, sinonasal anatomy is composed of intricate and subdivided air passages and drainage pathways that connect the sinuses.

Structure and Function

There are 4 paired sinuses in humans. They are all in line with pseudostratified columnar epithelium.

- The maxillary sinuses: Largest of the paranasal sinuses, located under the eyes in the maxillary bones.

- The frontal sinuses: Located superior to the eyes within the frontal bone

- The ethmoid sinuses: Formed from several discrete air cells within the ethmoid bone between the nose and eyed

- The sphenoid sinuses: Located within the sphenoid bone

The function of the paranasal sinuses is debated. However, they are implicated in several roles:

- Decreasing the relative weight of the skull

- Increasing the resonance of the voice

- Providing a buffer against facial trauma

- Insulating sensitive structures from rapid temperature fluctuations in the nose

- Humidifying and heating inspired air

- Immunological defense

To develop a strong understanding of paranasal sinus anatomy, it is also important to understand the anatomical relationships of the sinuses to surrounding structures. The lateral nasal wall contains many structures and recesses that are important for understanding paranasal sinus anatomy.

- Turbinates: Three to 4 bony shelves covered by erectile mucosa, serve to increase the interior surface area

- Meatuses: Three spaces located beneath each turbinate. The superior meatus provides drainage for the sphenoid and posterior ethmoid sinuses. The middle meatus provides drainage for the frontal, anterior ethmoid, and maxillary sinuses. The inferior meatus contains the orifice of the nasolacrimal duct

- Uncinate process: A sickle-shaped, thin, bony part of the ethmoid bone, covered by mucoperiosteum, medial to the ethmoid infundibulum and lateral to the middle turbinate

- Ethmoid infundibulum: This is a pyramidal space facilitating drainage of the maxillary, anterior ethmoid, and frontal sinuses. The superior attachment of the uncinate process determines the spatial relationship of the frontal sinus drainage (discussed in another section)

- Semilunar hiatus: This is a gap that empties the ethmoid infundibulum and is located between the uncinate process and the ethmoid bulla

- Osteomeatal complex (OMC): Region referring to the anterior ethmoids containing the ostia of the maxillary, frontal, and ethmoid sinuses. This is located lateral to the middle turbinate. While not a discrete anatomic structure, it is instead a collection of several middle meatus structures including the middle meatus, uncinate process, ethmoid infundibulum, anterior ethmoid cells, and ostia of the anterior ethmoid, maxillary, and frontal sinuses.

- Nasal Fontanelles: Area of the lateral nasal wall where no bone exists. The natural ostium of the maxillary sinus is located in the anterior fontanelle.

Maxillary Sinus

The maxillary sinus is located under the eyes in the maxillary bone. Adjacent structures include the lateral nasal wall, the orbital floor, and the posterior maxillary wall which contains the pterygopalatine fossa. The maxillary sinus is innervated by the infraorbital nerve (CN V2). The maxillary and facial arteries supply the sinus, and the maxillary vein supplies venous drainage. As mentioned already, the maxillary sinus drains into the ethmoid infundibulum. There is typically only one ostium per maxillary sinus; however, cadaver studies have shown 10% to 30% have an accessory ostium. The size of the maxillary sinus at adult stage is approximately 15 mL, making it the largest paranasal sinus.

Frontal Sinus

The frontal sinus is located superior to the orbit and within the frontal bone. The typical volume at the adult stage is 4 to 7 mL. The frontal sinus drains into the frontal recess via the middle meatus. As noted previously, this drainage can be variable, either medial or lateral to the uncinate, depending on its attachment. The frontal sinus vasculature consists of the supraorbital and supratrochlear arteries and ophthalmic and supraorbital veins. Similarly, it's innervation is provided by the supraorbital and supratrochlear nerves (CNV1). Several anatomical spaces/structures are important to frontal sinus anatomy:

- Frontal recess: Drainage space between the frontal sinus and semilunar hiatus that is bounded by the posterior wall of the agger nasi cell, lamina papyracea, and the middle turbinate.

- Frontal sinus infundibulum: Space that drains into the frontal recess that is located superior to the agger nasi cells

- Frontal cells: anterior ethmoid cells that pneumatize the frontal recess. These cells may cause obstruction or persistent sinus disease. They are located posterior and superior to the agger nasi cell, and there are 4 types as classified by Bent and Kuhn:

- Type I: Single cell above the agger nasi cell but below the floor of the frontal sinus

- Type II: Multiple cells above the agger nasi, may extend into the frontal sinus

- Type III: Single large cell that extends supraorbitally through the floor of the frontal sinus, attaches to the anterior table

- Type IV: Single isolated cell that is contained within the frontal sinus

Sphenoid Sinus

The sphenoid sinuses are located centrally and posteriorly within the sphenoid bone. They drain into the sphenoethmoidal recess located within the superior meatus. The sphenopalatine artery supplies the sinus, and venous drainage is via the maxillary vein. Innervation is provided by the sphenopalatine nerve, which is comprised of parasympathetic fibers and CN V2. The typical adult size is 0.5 to 8 mL. Several important structures have a close anatomical relationship to the sphenoid sinus. The carotid artery is located adjacent to the lateral wall of the sinus, and in 25% of patients, it is dehiscent in this area. The optic nerve is also located adjacent to the lateral wall of the sinus and can be dehiscent in up to 5% of individuals.

Ethmoid Sinuses

- There are 3 to 4 cells at birth and develop into 10 to 15 by adulthood for a total volume of 2 to 3 mL. They are located between the eyes. The anterior ethmoids drain into the ethmoid infundibulum, in the middle meatus. The posterior ethmoid sinuses drain into the sphenoethmoidal recess located in the superior meatus. The ethmoid sinuses are supplied by the anterior and posterior ethmoid arteries, respectively. These arteries are branches of the ophthalmic artery, which is a branch off of the internal carotid artery. This is an important anatomical relationship to realize because endovascular embolization of the ethmoid arteries should be avoided when treating epistaxis due to the possibility of retrograde movement of the embolization material into the ICA resulting in possible CVA. Ethmoid sinus venous drainage is by the maxillary and ethmoid veins. The anterior and posterior ethmoid veins provide innervation.

- The complex ethmoidal labyrinth can be reduced into a series of lamellae based on embryologic precursors. These lamellae are obliquely oriented and lie parallel to each other.

- The first lamella is the uncinate process.

- The second lamella corresponds to the ethmoid bulla.

- The third lamella is also known as the basal or ground lamella of the middle turbinate. This lamella serves as the division of the anterior and posterior ethmoids. The anterior part inserts vertically into the crista ethmoidalis. The middle portion attaches obliquely into the lamina papyracea. The posterior third attaches to the lamina papyracea as well but in a horizontal fashion.

- The fourth lamella is the superior turbinate.

- The agger nasi cell is the most anterior of the anterior ethmoid cells. It is found anterior and superior to the middle turbinate attachment to the lateral wall. The posterior wall of the agger nasi cell forms the anterior wall of the frontal recess.

- The ethmoid bulla is the largest of the anterior ethmoid cells that lies above the infundibulum. This structure is important because the anterior ethmoid artery courses over the roof of this cell.

Embryology

Development of the paranasal sinuses is heralded by the appearance of a series of ridges or folds on the lateral nasal wall at approximately the eighth week of gestation, known as the ethmoturbinals. Six to 7 folds emerge initially, but eventually, only 3 to 4 ridges persist through regression and fusion.

- First ethmoturbinal: rudimentary and incomplete in humans ascending portion forms the agger nasi descending portion forms the uncinate process

- Second ethmoturbinal: Forms the middle turbinate

- Third ethmoturbinal: Forms the superior turbinate

- Fourth and fifth ethmoturbinals: Fuse to form the supreme turbinate

As development progresses, furrows form between these ethmoturbinals, which leads to the establishment of rudimentary meati and recesses.

The frontal sinus originates from anterior pneumatization of the frontal recess into the frontal bone. The frontal sinus does not appear until the age of 5 to 6 years old. The sphenoid sinus develops during the third month of gestation. During this time, the nasal mucosa invaginates into the posterior portion of the cartilaginous nasal capsule to form a pouch-like cavity. The wall surrounding this cartilage is ossified in the later months of fetal development. Then, during the second and third year of life, the cartilage is resorbed, and the cavity becomes attached to the body of the sphenoid. By the sixth or seventh year of life, pneumatization of the sphenoid sinus progresses, and by the 12th year, the pneumatization is complete with pneumatization of the anterior clinoids and pterygoid process. The maxillary sinus is the first to develop in utero. The maxillary sinus shows a biphasic growth pattern, with growth at 3 and 7 to 18 years of age. The ethmoid sinuses are comprised of 3 to 4 air cells at birth. And by the time an individual reaches adulthood, they consist of 1 to 15 aerated cells.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The major artery of the maxillary sinus is the internal maxillary artery, a branch of the external carotid artery. The ethmoid and frontal sinuses have a variety of blood supplies, including meningeal vessels for the cribriform plate above the ethmoid sinuses, as well as the posterior wall of the frontal air cells. The sphenoid sinuses may derive blood supply from small branches of the cavernous internal carotid arteries. Rarely, an aneurysm of the internal carotid artery may invaginate into the sphenoid sinus, making endovascular coiling the preferred technique for aneurysm obliteration.

Nerves

The major nerve running below the frontal sinus is the first division of the fifth cranial nerve. The major nerve of the inferior aspect of the maxillary sinus is the second division of the fifth cranial nerve. This nerve has sensory but no specific motor functions, as opposed to the third division of cranial nerve five, the latter of which has both sensory (primarily skill of the jaw and the teeth) and motor functions (primarily muscles of mastication).

Muscles

The frontalis muscle runs over the frontal skull and sinus region and is part of the mechanism of facial expression. The levator muscles of the lips are anchored over the maxillary sinuses. The zygomatic projection of the maxilla is part of the anchorage of the masseter muscle, a powerful closure of the jaw.

Physiologic Variants

Nasal anatomy differs significantly among individuals; certain anatomic variations are relatively common. The variations may contribute to mechanical obstruction of the osteomeatal complex leading to rhinosinusitis.

Concha bullosa is defined as aeration of the middle turbinate. This variation can be either unilateral or bilateral. If large, a concha bullosa in the middle turbinate may lead to obstruction of the middle meatus or infundibulum.

The nasal septal deviation is an asymmetric bowing of the nasal cartilaginous septum. Such a bowing may compress the middle turbinate in a lateral fashion, which may lead to narrowing of the middle meatus. This variation is often congenital, but may also be secondary to nasal trauma.

The middle turbinate usually curves medially toward the nasal septum. However, when the turbinate curves laterally, the resultant anatomic variant is known as a paradoxical middle turbinate. Such a variant can narrow or obstruct the nasal cavity, middle meatus, or infundibulum.

The uncinate process is a structure that has multiple variations between individual patients. The superior attachment of the uncinate process has three major variations that help determine the anatomic configuration of the frontal recess and its drainage:

- An uncinate process that extends laterally to attach to the lamina papyracea or the ethmoid bulla, forming a terminal recess of the infundibulum with the frontal recess opening directly into the middle meatus

- An uncinate process that extends medially and attaches to the lateral surface of the middle turbinate, with the frontal recess draining into the infundibulum

- An uncinate process that extends medially and superiorly to directly attached to the skull base, with the frontal recess draining into the infundibulum

- Eighty percent of the time, the uncinate attaches to the lamina papyracea resulting in frontal sinus drainage medial to the uncinate, while 20% of the time, the uncinate attaches to either the skull base or middle turbinate, resulting in drainage lateral to the uncinate.

Haller cells are ethmoid air cells that extend laterally over the medial aspect of the roof of the maxillary sinus. If large enough, they may cause narrowing of the infundibulum. Onodi cells are lateral and posterior extensions of the posterior ethmoid cells. Horizontal septations around the sphenoid sinus delineate them. Importantly, these cells may surround the optic nerve tract, which can increase the risk of injury to the optic nerve during surgery.

Lastly, the height of the ethmoid roof can vary between patients and vary between each side in the same patient. When there is asymmetry of ethmoid roof height in a patient, the risk of intracranial penetration during FESS is higher.

These are only a few of the anatomic variations seen in sinonasal anatomy. While they represent the most common variations, the importance of having a sound understanding of the 3-dimensional anatomy is paramount to safe and effective endoscopic sinus surgery.

Surgical Considerations

Treatment of inflammatory disease of the paranasal sinuses involves both medical therapy and surgical treatment. There are several general guidelines for chronic sinusitis when considering surgical management:

- Preserve the mucoperiosteum and try not to leave the exposed bone

- Remove bony partitions and any osteitic bone in the area of disease as completely as possible

- Extend the dissection one step beyond the extent of disease if possible

- Preserve the middle turbinate if possible

Clinical Significance

Paranasal sinuses are prone to inflammation and infection. If the paranasal sinuses become blocked from secretions or a mass, the drainage of mucus is interrupted, and sinusitis can result. The maxillary sinus may be involved from any process in the teeth or the gums. The frontal and maxillary sinuses may be involved in allergies. Depending on the cause, sinusitis is treated with corticosteroids, decongestant, nasal irrigation, and hydration. Rarely surgical intervention may be required to enhance drainage.

Malignancies of the paranasal sinuses are rare. The majority of cancers occur in the maxillary sinus and are more common in men than women. Maxillary sinus malignancies occur between ages 45 to 70, and the most frequent is a sarcoma. Even though metastases are rare, these malignancies are locally invasive and destructive. Diagnosis in most cases is delayed, and the prognosis is poor.

Acute rhinosinusitis (ARS) and chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) are both defined as symptomatic inflammation of the nose and paranasal sinuses. The 2 are distinguished based on the duration of the complaints. Generally speaking, acute rhinosinusitis is widely considered to be an infectious disorder. On the other hand, chronic rhinosinusitis is typically defined as an inflammatory disorder. In ARS, the underlying etiology is typically viral or bacterial, and occasionally fungal. The pathogenesis of ARS involves infection followed by tissue invasion.

The most widely accepted classification system divides CRS into CRS with and without nasal polyps (CRSwNP and CRSsNP, respectively) based on nasal endoscopy. Originally, it was felt that CRSsNP was a disease process characterized by persistent inflammation that led to incomplete resolution of ARS. CRSwNP, on the other hand, was felt to be a noninfectious disease process with unclear etiology, perhaps related to atopy. Current research has instead revealed that the etiology and pathogenesis of either form of CRS is much more complex.