Parotitis

- Article Author:

- Michael Wilson

- Article Editor:

- Shivlal Pandey

- Updated:

- 9/10/2020 8:02:57 AM

- For CME on this topic:

- Parotitis CME

- PubMed Link:

- Parotitis

Introduction

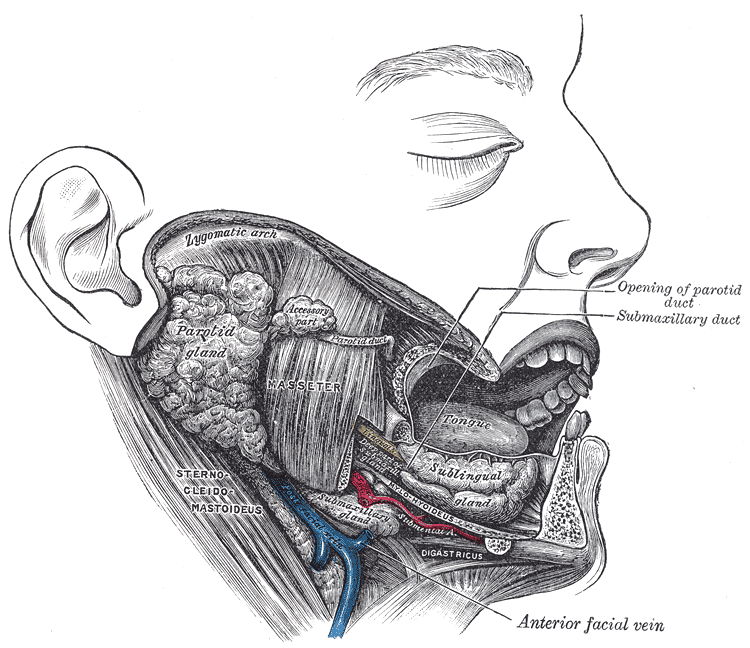

The parotid gland is salivary gland others include submandibular and sublingual glands. It is enclosed within a fascial capsule and comprises a superficial lobe and a deep lobe separated by the facial nerve. It is an exocrine gland that secretes saliva into the oral cavity after parasympathetic stimulation. The Stensen canal is the primary excretory duct for the parotid gland, passing through the masseter muscles, penetrating the buccinator, and then into the oral mucosa lateral to the second maxillary molar. The saliva secreted aids in chewing, swallowing, digestion, and phonation. Saliva contains electrolytes, mucin, and digestive enzymes like amylase.

Parotitis is inflammation of the parotid glands, and the is the most common among the inflammation of the major salivary glands. Parotitis can present as a local process or can be a manifestation of systemic illness.

Predisposing factors include dehydration, malnutrition, immunosuppression, sialolithiasis, oral neoplasms, and medications, causing decreased salivation. Rare complications of parotitis or parotid procedures include osteomyelitis, Lemierre syndrome, sepsis, organ failure, and facial paralysis.[1][2]

Etiology

Parotitis can be infectious or due to a variety of inflammatory conditions. Acute bacterial parotitis is uncommon, but especially concerning in the extremes of age, occurring in the elderly (especially after abdominal surgery), and, although rare, can be fatal in neonates. Cystic fibrosis, dehydration, malnutrition, abdominal surgery, immunosuppression, and dental infections increase the risk of acute bacterial parotitis. The most common cause is Staph aureus; other bacterial causes can include Strep viridans, E. coli, and anaerobic oral flora. Consider group B Streptococcus (GBS) infection in neonates. Melioidosis from Pseudomonas pseudomallei from contaminated water can be common in Southeast Asia.[3] Mycobacterium tuberculosis is a rare cause of parotitis seen in immunocompromised patients with delayed diagnosis. Hospitalized or immunosuppressed patients may develop candida parotitis.

Of the many viral infections resulting in parotitis, mumps (a paramyxovirus) is the classic cause of epidemic parotitis.[4] Other viral causes include coxsackie A virus, cytomegalovirus, echovirus, enterovirus, influenza, and parainfluenza viruses.

Inflammatory conditions resulting in parotitis include sarcoidosis, Sjögren syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus.

Uncommon causes of parotitis can include trauma, surgery (such as manipulation during carotid endarterectomy), drug exposure (such as iodides, heavy metals, phenylbutazone, thiouracil) and radiation therapy, especially whole brain radiation therapy can lead to parotitis.[5]

Chronic nonspecific parotitis and recurrent parotitis of childhood (juvenile recurrent parotitis) have no definite infectious cause. However, antibiotics are frequently used to treat the latter but may occur due to scar tissue, stricture, and sialectasis.[6]

Epidemiology

Acute bacterial parotitis is uncommon, has a similar male-female ratio, but is more common in the elderly, and accounts for an estimated 0.01 to 0.02% of hospital admissions and occurs in 0.002 to 0.04% of postoperative patients.[7] Acute neonatal parotitis is rare, with a prevalence of less than 4 per 10000 admissions.[8]

Chronic parotitis occurs equally in males and females. Sjogren syndrome is nine times more common in women than men, whereas recurrent parotitis of childhood is more common in males. Sarcoidosis is most common in African Americans adults with onset in the 20 to 40-year age range.

Pathophysiology

The presence of a ductal valve creates a unidirectional flow of saliva out the gland, which prevents bacteria from entering. However, at times, this valve may become incompetent and result in ascending bacterial infection. Dehydration or drying medications, such as atropine, antihistamines, and psychotropic agents, which decrease salivary production and flow, can increase the risk of parotitis of either infectious or inflammatory cause. Sialolithiasis is a common condition where calculi formed from inorganic crystals can obstruct the gland duct, although less common in the parotid than submandibular glands due to serous rather than mucoid saliva. Bacteria trapped behind a high-grade obstruction can proliferate and result in acute suppurative parotitis.[9] In the hospital setting, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and atypical infections such as candida, should be considered.

In autoimmune parotitis (such as Sjögren or rheumatoid arthritis), an antigen-antibody complex is endocytosed into epithelial cells, processed into a human leukocyte antigen expressed on the cell surface and recognized by specific CD4 T-lymphocytes which release cytokines and chemotactic factors augmenting more CD4 activation. B-lymphocytes enter the acini and produce antibodies presenting antigens to CD4 T-cells, with resultant oligoclonal expansion and acinar destruction that can increase the risk of neoplastic transformation. These autoimmune causes result in chronic parotitis, often termed chronic punctate parotitis. Chronic parotitis eventually results in scar tissue, stricture, and sialectasis.[10]

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) can result in asymptomatic, firm parotid swelling, more pronounced in children than adults, due to CD8+ lymphocytes responding to HIV or other viruses, such as Epstein Barr, hepatitis C, cytomegalovirus, or adenovirus, infiltrating and ultimately depositing in the gland.

Sarcoidosis can lead to parotid gland inflammation, but less commonly than the lungs, lymph nodes, and skin. Noncaseating granulomas are present in both parotid glands causing swelling but minimal symptoms or inflammation. Rarely, sarcoid involvement can be severe and result in the Heerfordt-Waldenström syndrome characterized by fever, anterior uveitis, parotid enlargement, and facial nerve paralysis.

History and Physical

Patients with parotitis complain of progressive enlargement and pain in one or both parotid glands. Bilateral parotid involvement is typical for mumps and inflammatory conditions, whereas unilateral parotid swelling, pain, and presence of fever are more suggestive of bacterial cause. Patients will complain of pain with mastication localizing to the parotid and radiating to the ear, often subsiding within 30 to 60 minutes after eating.

On exam, the parotid gland typically presents as enlarged, edematous and tender, often indurated and sometimes warm. When the parotid is gently massaged in a posterior to anterior direction, bacterial parotitis will exhibit purulent drainage from Stensen duct, whereas small yellow crystal chunks favor an autoimmune cause.[11] Acute parotitis is typically tender and warm, whereas chronic autoimmune parotitis is frequently non-tender. Sialolithiasis presents with swelling around Stensen duct, often with a visible or palpable stone.

Mumps parotitis cases present with fever, headache, myalgia, malaise, and anorexia due to painful mastication. Some children can present with recurrent parotitis of childhood (juvenile recurrent parotitis), with symptoms similar to mumps, but the cause is unknown. Recurrent episodes lasting days to weeks can recur from early childhood to adolescence.

Evaluation

Parotitis is a clinical diagnosis. If drainage from Stensen duct is present, send a specimen for Gram stain and culture and sensitivity if bacterial parotitis is suspected. Serum amylase levels will be elevated in many cases but are nonspecific. Amylase levels are less likely to rise in Sjogren syndrome or parotid tumors. Elevated inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), are supportive but also nonspecific.

Imaging is rarely necessary for the evaluation of parotitis. Ultrasonography might confirm sialolithiasis, and can identify abscess, differentiate between solid and cystic masses within the gland and identify hypoechoic areas frequently seen in punctate sialectasis.[12] Plain radiography or computed tomography (CT), with or without contrast, can confirm sialolithiasis, and rarely multiple parotid calcifications in chronic parotitis. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be used to differentiate between chronic parotitis and neoplastic changes within the gland. In cases of HIV parotitis, MRI can be diagnostic with the demonstration of multiple cyst formation.

Sialography, performed by otolaryngologist or dental specialist, is the historical “gold standard” and could provide detailed visualization of the parotid ductal system and acini; however, it is not a common procedure.[13] Instead, sialendoscopy has proven useful in cases of chronic parotitis and juvenile recurrent parotitis.[6][14][15][16]

Incisional or fine-needle biopsy of the parotid tail, performed by an experienced surgeon carefully avoiding the facial nerve, can be sent for culture for suspected infectious source or histopathology useful to determine parotitis etiology. Lymphoepithelial cysts occur in HIV parotitis, noncaseating granulomata are present in sarcoid parotitis, and lymphocytic invasion with acinar destruction can be characteristic of neoplastic lymphoma.

Treatment / Management

The treatment of parotitis is primarily symptomatic control with a focus on local application of heat, gentle glandular massage from posterior to anterior, sialagogues, and adequate hydration. Simple anti-inflammatory analgesics, such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen, are sufficient for discomfort. If purulent drainage expresses during the glandular massage, culture and sensitivities should be obtained by swab or needle aspiration to guide proper antibiotic therapy.[17][7][18]

Sialolithiasis, a cause of parotitis, can resolve with warm compresses, massage, and sialagogues (sour food or lemon candy), but occasionally requires extraction. After local anesthesia with topical or infiltrated lidocaine, the duct can be dilated or filleted with scissors, then massaged to squeeze out the stone. Extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy, to fragment the stone before extraction, or interventional sialendoscopy by otolaryngology specialists are options for refractory cases.

Parotitis that is suspected to be secondary to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or chronic autoimmune conditions (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis or Sjögren syndrome) should focus on treating the underlying condition, such as anti-retroviral therapy or steroids.

Treatment of acute bacterial parotitis should include intravenous (IV) hydration, analgesics, and 7 to 10 days of IV antibiotics.[18] In community-acquired parotitis, first-line treatment is with antistaphylococcal penicillin (nafcillin, oxacillin), first-generation (cefazolin), vancomycin, or clindamycin for suspected methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA).[19] For health-care-associated parotitis, use cefoxitin, ertapenem, or ampicillin/sulbactam, with levofloxacin, clindamycin, or piperacillin-tazobactam as alternatives. For patients at high risk of MRSA, start with vancomycin or use linezolid or daptomycin as alternatives. Parotitis, in case of dental infection, should prompt the use of clindamycin or metronidazole (anaerobic coverage) and ceftriaxone or piperacillin-tazobactam as an alternative.

In neonates, where acute parotitis can be life-threatening, antibiotics are usually IV gentamicin or levofloxacin and anti-MRSA antistaphylococcal antibiotics. If clinical improvement does not take place within 48 hours, parotidectomy may be necessary. The rare parotitis from extrapulmonary tuberculosis responds well to antitubercular medications.

Consult otolaryngology early for incision and drainage for cases of acute parotitis refractory to conservative measures of hydration and antibiotics. Specialists might consider saline irrigation of the duct system to remove inspissated mucus or pus.[7]

Treatment of HIV parotitis may include antiviral therapy, low dose radiation, or partial parotidectomy to reduce glandular size.[20][21]

Superficial parotidectomy is usually last resort for chronic parotitis and may involve ligation of the duct or instillation of methylene violet.[22] Surgery may be necessary for disfiguring swelling, chronic autoimmune parotitis at risk for neoplastic lymphoma, or adjacent inflammation resulting in facial nerve paralysis.

Differential Diagnosis

Obstructive parotitis follows sialolithiasis (stone in the gland or duct). Occasionally calculi can extravasate out of the gland and into the neck, generating an inflammatory mass.

Pneumoparotitis occurs when air enters the parotid past the one-way valve of the parotid ducts from elevated pressures in the oral cavity, such as with wind instrument players, scuba divers, and glass blowers. Occasionally bacterial parotitis can result, and rarely parotid gland rupture.[23][24]

Sialosis (sialadenosis) is a noninflammatory disorder that usually produces bilateral parotid gland enlargement and is characterized by soft, non-tender, bilaterally enlarged parotid glands. It commonly presents in people between the ages of 20 to 60 years of age and has an equal prevalence between males and females. The etiology is currently unknown, but may be due to inappropriate autonomic nervous system stimulation, and may be associated with endocrine disorders (diabetes), nutritional disorders (pellagra or bulimia) and medications (such as thioridazine or isoprenaline). The diagnostic basis is bilateral involvement and biopsy showing acinar enlargement with hyperdense cytoplasmic granules.

Prognosis

Parotitis carries a relatively favorable prognosis for all forms, and underlying diseases determine the prognosis. Most cases of parotitis resolve spontaneously or with antibacterial treatment without recurrence or complication. Children may present with juvenile recurrent parotitis that can be symptomatic for days to weeks at a time and can require a partial parotidectomy. Neonatal parotitis can be life-threatening. Rarely, acute bacterial parotitis can lead to osteomyelitis, sepsis, and organ failure and death.

Complications

Chronic bacterial parotitis can result from chronic autoimmune diseases or untreated bacterial infections with resultant glandular ductal inflammation and ductal stenosis and decreased salivary flow. Rarely fistula formation can occur.

Neoplasm, such as lymphoma, can result from chronic autoimmune parotitis.

Facial paralysis is a rare complication but can occur from chronic inflammation from Sjogren syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, or the rare sarcoidosis Heerfordt-Waldenstrom (or uveoparotid fever) syndrome.[25] Parotid biopsy or surgery can also result in facial nerve injury.

Despite the maxillary and external carotid arteries traversing through the parotid gland, vascular complications from parotitis are rare, although parotid surgery should be cautious to avoid vascular injury.

Xerostomia can be uncomfortable but also interferes with feeding due to alterations in taste (dysgeusia) and chewing process from lack of lubricant necessary for food bolus formation. Malnutrition can result.

Mumps parotitis can be associated with meningoencephalitis in as many as 10%, pancreatitis, orchitis in as many as 30% of post-pubertal males, or sensory neural hearing loss.

Parotitis can rarely result in septic thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein (Lemierre syndrome, usually from oropharyngeal Fusobacterium necrophorum infection) due to proximity and shared venous drainage.[26]

A rare parotitis complication involving excess sweating (hyperhidrosis) and numbness on the cheek in front of the ear during salivation (eating or thinking of food), called Frey syndrome (auriculotemporal syndrome, also Baillarger or Dupuy or Frey-Baillarger syndrome), caused by damage to the auriculotemporal nerve a branch of the mandibular trigeminal nerve.[27]

Eagle syndrome, a pharyngeal foreign body sensation and cervicofacial pain with an elongated styloid process, which is much more commonly caused by trauma or tonsillectomy, can rarely follow acute parotitis.[28][22]

Consultations

Consider otolaryngology specialists consultation for parotitis of uncertain etiology, and especially for acute bacterial parotitis refractory to treatment and juvenile recurrent parotitis. Other team members needed for the care of a patient with parotitis include

- Primary care provider

- Dietician/nutritionist

Deterrence and Patient Education

The most important directive for the patient is to maintain adequate hydration. Additionally, avoid medications that can dry the mouth, especially antihistamines, decongestants or antidepressants, diuretics, and some antihypertensive, muscle relaxant, and antibiotic agents. Avoid drug exposures such as cocaine, methamphetamine, alcohol, chewing tobacco, or smoking tobacco or marijuana, which can also lead to decreased salivary flow.

Vaccination with MMR (measles, mumps, rubella) has dramatically decreased the incidence of mumps parotitis (by 99% in the United States). However, this disorder can still occur in unimmunized or partially immunized individuals with less than the recommended three vaccinations.[4]

Pearls and Other Issues

- Staph aureus is the most common causative bacteria of acute suppurative parotitis, and treatment for MRSA should merit consideration when at risk.

- Failure of antibiotic therapy for acute suppurative parotitis, especially in neonates or in the presence of sepsis, should prompt otolaryngology consultation for surgical intervention such as incision and drainage.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Parotitis can occur in any patient and is not unusual after surgery. The condition is not always easy to diagnose and thus is best managed by an interprofessional team. The nurses are often the first to note the problem in postoperative patients. While there is no generic preventive method, the nurse should educate the patient on adequate hydration and maintaining good oral hygiene. The pharmacist should ensure that the anticholinergic medications have been discontinued, and assist the providers in therapeutic agent selection to treat parotitis based on the underlying cause, while also performing medication reconciliation and verifying dosing.

While the condition is treated supportively in most cases, consultation with an ENT surgeon may be required. Nursing can then followup and monitor therapy effectiveness and watch for adverse events. The condition may last a few days and can be painful; hence, optimal pain control is necessary. The dietitian should be consulted on nutrition, as many patients are not able to chew or even swallow. Close communication between interprofessional team members is vital to improving outcomes. [Level 5]

(Click Image to Enlarge)