Paroxysmal Supraventricular Tachycardia

- Article Author:

- Yamama Hafeez

- Article Editor:

- Shamai Grossman

- Updated:

- 11/7/2020 7:07:46 AM

- For CME on this topic:

- Paroxysmal Supraventricular Tachycardia CME

- PubMed Link:

- Paroxysmal Supraventricular Tachycardia

Introduction

Paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia (PSVT) accounts for intermittent episodes of supraventricular tachycardia with sudden onset and termination. PSVT is part of the narrow QRS complex tachycardias with a regular ventricular response in contrast to multifocal atrial tachycardia, atrial fibrillation, and atrial flutter. SVTs are classified based on the origin of the rhythm and whether the rhythm is regular or irregular.[1][2][3][4][5][6]

Atrial in origin and regular rhythm:

- Sinus tachycardia

- Inappropriate sinus tachycardia

- Sinoatrial nodal reentrant tachycardia

- Atrial flutter

- Atrial fibrillation

Atrial in origin and irregular rhythm:

- Multifocal atrial tachycardia

- Atrial flutter with variable block

- Atrial fibrillation

AV node in origin and regular rhythm:

- Junctional tachycardia

- Atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia

- Atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia

AV node in origin and irregular rhythm:

- None

SVT is known to occur in individuals of all ages, but treatment is often difficult. The clinical presentation of SVT is variable- ranging from asymptomatic to severe palpitation. Electrophysiologic studies are usually necessary to determine the pathophysiology of impulse formation and pathways of conduction.

Etiology

Numerous conditions and medications can lead to PSVT in patients. [1][7][8][9]

Some of these conditions and medications are listed below:

- Hyperthyroidism

- Caffeinated beverages

- Nicotine

- Hydralazine

- Atropine

- Adenosine

- Verapamil

- Salbutamol

- Ecstasy

- Cocaine

- Amphetamines

- Alcohol

- Digoxin toxicity

- Myocardial infarction

- Structural heart disease

- Ebstein anomaly

- Pericarditis

- Myocarditis

- Cardiomyopathy

- Pulmonary embolism

- Rheumatic heart disease

- Mitral valve prolapse

- Pneumonia

- Chronic lung disease

- Chest wall trauma

- Anxiety

- Hypovolemia

- Hypoxia

Epidemiology

In the United States, the prevalence of PSVT is approximately 0.2%, and it has an incidence of one to three cases every thousand patients. The most common type of PSVT is atrial fibrillation with a prevalence rate of approximately 0.4% to 1% occurring in men and women equally, it is projected to affect as many as 7.5 million patients by 2050. The risk of developing PSVT was found to be twice in women as compared to men in a population-based study, with the prevalence of the PSVT higher with age. Atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia is found more commonly in patients who are middle-aged or older. Whereas PSVT with an accessory pathway is most common in adolescents, and their occurrence decreases with age.[10][11][12]

Besides occurring in healthy people. PSVT can also occur after a myocardial infarction (MI), rheumatic heart disease, mitral valve prolapse, pneumonia, chronic lung disease, and pericarditis. Digoxin toxicity is often associated with PSVT.

Pathophysiology

PSVT is often due to different reentry circuits in the heart, where less frequent causes include enhanced or abnormal automaticity and triggered activity. Reentry circuits include a pathway within and around the sinus node, within the atrial myocardium, within the atrioventricular node or an accessory pathway involving the atrioventricular node.[13][14][15] Different types of PSVT result depending on the existing circuits, and examples are:

- Sinus node: Sinoatrial node reentrant tachycardia

- Atrial myocardium: Atrial flutter, atrial fibrillation, and multifocal atrial tachycardia

- Atrioventricular node: Atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia, atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia

Histopathology

Under most circumstances, careful examination in patients with PSVT will show reentry circuits discussed above. No specific histopathologic findings are found in patients with PSVTs secondary to triggered activity and enhanced or abnormal automaticity.[15]

History and Physical

The severity of symptoms in patients with PSVT depends on any underlying structural heart disease, the frequency of PSVT episodes, and the patient's hemodynamic reserve. Usually, patients with PSVT present with symptoms of dizziness, syncope, nausea, shortness of breath, intermittent palpitations, pain or discomfort in the neck, pain or discomfort in the chest, anxiety, fatigue, diaphoresis, and polyuria secondary atrial natriuretic factor secreted mainly by the heart's atria in response to atrial stretch. The most common symptoms are dizziness and palpitations. Patients with PSVT and a known history of coronary artery disease may present with a myocardial infarction secondary to the stress on the heart. Patients with PSVT and a known history of heart failure may come in with acute exacerbation. Frequent PSVTs in a patient can result in new-onset of heart failure secondary to tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy.[16]

A detailed history of the patient with PSVT should include past medical and cardiac history, time of symptom onset, prior episodes, and treatments. The patients' current medication list must be obtained. Investigations of involvement in physical activities such as exercise or outdoor sports should be made, as patients who have symptomatic PSVT's avoid such hobbies. Patients presenting with PSVTs should get a thorough physical exam, including vital signs (respiratory rate, blood pressure, temperature, and heart rate) to help assess their hemodynamic stability.[17]

Evaluation

A significant component of evaluation for a patient who presents with signs and symptoms of PSVT is history and physical exam. These should include vital signs (respiratory rate, blood pressure, temperature, and heart rate), review of the patient's medication list, and a 12-lead electrocardiogram. During an evaluation, a health care provider should establish if the patient is hemodynamically stable and whether they have any underlying ischemic heart disease or heart failure. Digoxin toxicity should be ruled out.

Healthcare providers should consider thyroid function testing, pulmonary function testing, including routine blood work, and echocardiography as part of their initial evaluation of patients presenting with symptomatic PSVTs.[18][19]

ECG features:

- Sinus tachycardia with a heart rate more than 100 bpm with normal P waves

- Atrial tachycardia with a heart rate between 120-150 bpm. The P wave morphology may be different from normal sinus rhythm

- Multifocal atrial tachycardia with heart rates from 120-200 bpm with 3 or more different P wave morphologies

- Atrial flutter with a heart rate of 200-300 bpm

- Atrial fibrillation with irregularly irregular rhythm and no visible P waves

- AVNRT with a heart rate of 150-250 bpm, P waves before or within the QRS complex, short PR interval

- AVRT with a heart rate between 150-250 bpm, narrow QRS complex in orthodromic conduction and wide QRS complex in antidromic conduction

Treatment / Management

Treatment of PSVT in a patient is dependent on the type of rhythm present on the electrocardiogram and the patient's hemodynamic stability. Patients presenting with hypotension, shortness of breath, chest pain, shock, or altered mental status are considered hemodynamically unstable, and their electrocardiogram evaluation must be done to determine if they are in sinus rhythm or not. If they are not in sinus rhythm, these patients should undergo urgent cardioversion. If they are determined to be in appropriate sinus tachycardia, then their underlying etiology must be treated. For any manifestations of cardiac ischemia, intravenous beta-blockers should be considered. If they have inappropriate sinus tachycardia on the electrocardiogram and are determined to be hemodynamically unstable, treatment with intravenous beta-blockers may be appropriate.[20][21][22]

If on the initial evaluation, a patient is to found to be hemodynamically stable, then the treatment of the patient depends on the specific PSVT present on the electrocardiogram. If the 12-lead electrocardiogram shows that the rhythm is irregular and P waves are absent, then the patient should be appropriately treated for atrial fibrillation. If the rhythm on the electrocardiogram is irregular and flutter waves are present, then the patient should be treated for atrial flutter. If the rhythm on the electrocardiogram is irregular and multiple P wave morphologies are present, then the patient should be treated for multifocal atrial tachycardia.[23]

In patients who are hemodynamically stable and showing a regular rhythm with visible P waves on the electrocardiogram, then an assessment of the atrial rate, the relationship between the atrial and ventricular pacing, P-wave morphology and the P-wave position in the rhythm cycle is required. Type of PSVT present (atrial tachycardia, multifocal atrial tachycardia, atrial flutter, atrial flutter with a variable block, intra-atrial reentrant tachycardia, sinus tachycardia, sinoatrial node reentrant tachycardia, atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia, atrioventricular reciprocating tachycardia, junctional ectopic tachycardia, and nonparoxysmal junctional tachycardia) determines the treatment.[24][25]

In patients who are hemodynamically stable and have an electrocardiogram that shows a regular rhythm with undetectable P waves, Valsalva maneuvers, carotid sinus massage, or intravenous adenosine might be used to slow the ventricular rate or convert the rhythm into sinus rhythm and thus aid in the diagnosis. In some instances, increasing the electrocardiogram paper speed from 25 mm per second to 50 mm per second might help as well. If intravenous adenosine does not work, then intravenous or oral calcium channel blockers or beta-blockers should be used. Patients with PSVTs must also undergo evaluation for any underlying pre-excitation syndrome, and patients who fail medical treatment or those who might need radiofrequency catheter ablation need cardiology consultation.[26][27][28]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential includes: [29][30]

- Atrial tachycardia

- Multifocal atrial tachycardia (MAT)

- Atrial flutter

- Atrial flutter with variable block

- Atrial fibrillation

- Intraatrial reentrant tachycardia

- Sinus tachycardia

- Inappropriate sinus tachycardia

- Sinoatrial node reentrant tachycardia

- Atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia

- Atrioventricular reciprocating (reentrant) tachycardia

- Junctional ectopic tachycardia

- Nonparoxysmal junctional tachycardia

Prognosis

In cases with no structural heart disease, the prognosis of PSVT is reasonably good. For patients with structural heart disease, the prognosis is often guarded. The arrhythmia may come on suddenly and last anywhere from a few seconds to several days. Most patients develop anxiety, a sense of doom, and others may develop hemodynamic compromise. The arrhythmia can result in congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction, and pulmonary edema.

Complications

If not identified promptly symptomatic complications such as syncope, fatigue, or dizziness can occur.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Educating patients at risk for this rhythm and making a closed-loop communication between them and their providers can help further improve the management of these rhythms. If available, patient education should be provided using resources familiar to the patient including online resources and pamphlets.

Pearls and Other Issues

Frequent PSVT can result in tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy, a study on pregnant females found that PSVT in the first to second gestational month increase the chances of the child developing ostium secundum atrial septal defect.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Treatment of PSVT can involve an interprofessional team, including emergency department physicians and nurses, cardiologists and cardiology nurses, primary care providers, and pharmacists. Emergency medical technicians are often the first to encounter patients and provide treatment. The team should evaluate, as outlined above. Nurses, pharmacists, and physicians can provide education. Pharmacists should educate patients about medication side effects and compliance, as well as checking for drug interactions. [Level 5]

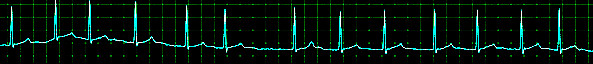

(Click Image to Enlarge)

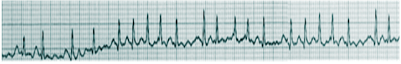

(Click Image to Enlarge)

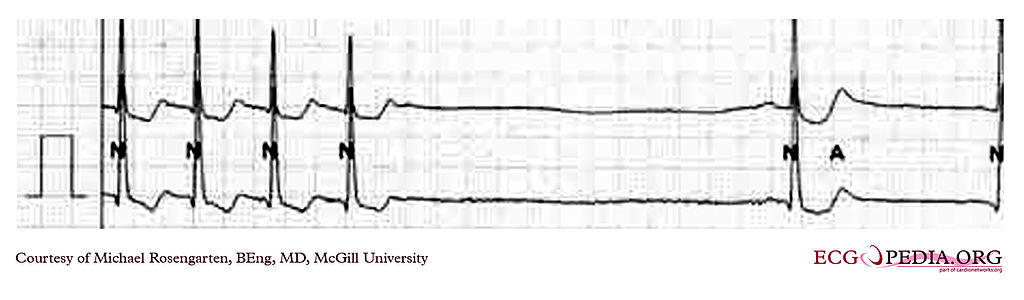

(Click Image to Enlarge)

This is a recording of the termination of a supraventricular tachycardia at about 130/min. which terminates and leaves a pause and then sinus bradycardia. This is a from of "tachy/brady" syndrome where a tachycardia is followed by a bradycardia.

Contributed by McGill University, Micheal Rosengarten, BEng, MD