Plague

- Article Author:

- Robert Dillard

- Article Editor:

- Andrew Juergens

- Updated:

- 8/10/2020 4:53:20 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Plague CME

- PubMed Link:

- Plague

Introduction

Plague is a zoonotic infection that has affected humans for thousands of years. In humans, the primary plague syndromes are bubonic, septicemic, and pneumonic. All of these result from infection with the gram-negative bacillus Yersinia pestis. The typical life-cycle of Y. Pestis starts within an insect vector followed by transmission to a mammalian host, typically rodents or other wild animals. Humans are only affected as incidental hosts. Despite this, Y. pestis is arguably one of the most important microbes in human history. It has caused three documented pandemics, with the “black death” in 14th century Europe leading to the death of up to 30% of the population. The most recent pandemic began in the late 19th century in Asia and India, and it continues today in Africa. Outside of this, the bacterium remains endemic in the Americas and Asia and also exists as a potential bioterrorism threat, spurring ongoing vaccine development.[1][2]

Etiology

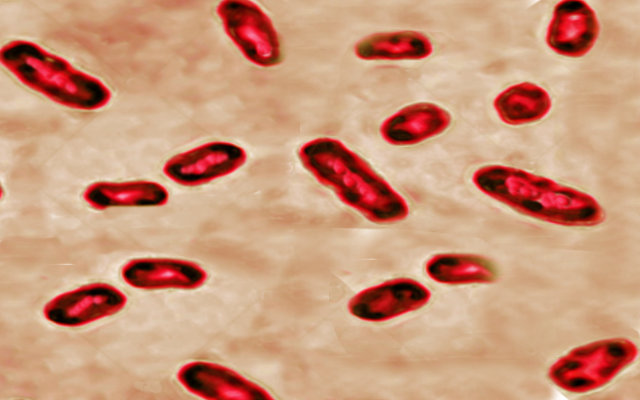

The sundry clinical presentations of plague result from a single bacterium of the enterobacteria family, Yersinia pestis.[2] Y. Pestis emerged as a genetic clone of Yersinia tuberculosis (an enteral pathogen) after the acquisition of three pathogenic plasmids several thousand years ago.[1][3] The bacterium is enzootic in rodents with insects serving as the primary vector. Rattus rattus (the domestic black rat) and Rattus novegicus (the brown sewer rat) are the most common hosts, while Xenopsylla cheopis (the oriental rat flea) is the most common and efficient vector. Humans contract the bacterium typically through the bite of an infected flea but may contract the disease in many other ways. Cases of plague contracted via direct handling of animal tissue with open skin lesions, inhalation of aerosolized bacteria, consumption of infected animals, and human to human spread have all been documented.[1]

Epidemiology

The plague has arguably been most impactful as three historical pandemics. The first, known as the Justinian Plague, occurred throughout the Mediterranean in the 6th Century during the reign of the Roman emperor Justinian. The second was the black death of 14th century Europe, and the third began in China in the late 19th century, leading to the deaths of millions in China and India.[4] Over the first decade of the 21st Century, 21725 cases were reported with 1612 deaths, for a mortality rate of 7.4%, with the majority of the cases affecting East and Central Africa.[5][2] Since the mid-20th century, the plague has been most active in Madagascar, with a total of 13234 cases from 1998 to 2016. In the US from 2000 through 2009, 57 cases were reported with 7 deaths.[5] Overall, plague has been rare in the US over the 20th century, thought to be because much of the affected area (New Mexico, Colorado, California, and Texas) is mostly uninhabited. Regardless of location, the spread of plague is seasonal, based on the ecology of rodents and their vectors in a particular region. For example, plague season in Madagascar stretches from September through March, while in the US, most cases occur between February and August.[4][1] All ages and sexes are susceptible to the disease. In recent years, there may be a slight predominance in males and children, though the accuracy and significance of this are unknown.

The most critical risk factor is exposure to the insect vector and rodent host in an area where the disease is active. Bites or scratches from infected cats can also spread disease. Person-to-person transmission is possible with pneumonic plague. Disease prevalence is higher in warm climates, especially for impoverished populations that live in housing or shelters that are not rat proof.[1] In the United States, the risk of plague is highest in the southwestern states. Half of the cases occur in young people aged 12 to 45 years, and more commonly affects men and those engaging in outdoor activity. [https://www.cdc.gov/plague/maps/index.html]

Suspected instances of plague require reporting to the appropriate local health department. In the United States, data on these cases are reported through local and state agencies and collected by the Centers for Disease Control.[6]

Pathophysiology

Although other means of contraction exist, Yersinia Pestis classically travels from enzootic rodent to a flea vector, in whom it forms a blockage in the gastrointestinal tract. This blockage causes flea to feed more often and regurgitate Y. Pestis into the host with each bite.[4] Following entering the host, Y. Pestis has many means of avoiding the immune system and typically travels to lymph nodes to propagate within macrophages. After release from macrophages, the bacterium causes a pro-inflammatory response that leads to clinical symptoms.[2][7] Due to the pathophysiologic involvement of lymph nodes, 80 to 95% of Y. pestis infections present as the suppurative adenitis known as bubonic plague.[4] This presentation may get bypassed for primary infection of the blood, known as septicemic plague, or lungs, pneumonic plague. Septicemic plague presents as hypotension and shock without a bubo, and pneumonic plague patients demonstrate high fever, cough, chest pain, and hemoptysis.[4]

History and Physical

The most common presentation of Y. pestis infection in humans is bubonic plague.; this begins with a bite from a flea and a 2- to 8-day incubation period. In 25% of cases, there may be a skin lesion at the site of the bite. This lesion presents differently in patients – possibly pustular, vesicular, papular, or an eschar – and are often not noticed. Following this, patients experience a sudden onset of fever, chills, headache, general weakness. Within the next day, a bubo develops. The bubo begins as intense pain in an area of regional lymph nodes, most commonly inguinal, followed by axillary or cervical nodes. Following this, swelling in the area of the bubo occurs, and the pain may be so intense that patients avoid movement. A bubo may be singular or present as a cluster of nodes, but the masses are typically non-fluctuant with overlying warmth. In addition to fever, other vital signs abnormalities include tachycardia and hypotension progressing to shock. In addition to the bubo, the physical exam may demonstrate hepatosplenomegaly.

Septicemic plague presents similarly to bubonic plague in all signs, but there is no associated bubo.

Pneumonic plague can occur as a primary or secondary location of the infection. It most commonly occurs following hematogenous spread from the bubo and leads to cough, chest pain, and hemoptysis in addition to the typical high fever associated with the plague. It may occur with or without buboes. Primary inhalational pneumonic plague occurs following inhalational exposure to another pneumonic plague patient with a cough. Rarer presentations include meningitis, which usually occurs secondary to the bubonic plague that has not received treatment, and pharyngitis, which presents similarly to other forms of pharyngitis with significant inflammation of anterior cervical lymph nodes. Plague sometimes may also present with prominent nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain before the presence of buboes or sepsis, making initial diagnosis difficult.[8][4]

Evaluation

Any patient suspected of plague should undergo until cleared. For pneumonic plague, the Centers for Disease Control recommend standard and droplet precautions for 48 hours after the initiation of appropriate antibiotic therapy. [https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/pdf/guidelines/isolation-guidelines-H.pdf] Additionally, laboratory personnel should be informed of any suspected infection to allow for proper handling of samples, since pneumonic plague is transmittable through the standard handling of samples and cultures.

For all presentations of Y. pestis, high suspicion by the clinician is required to make the diagnosis. A presumptive diagnosis occurs in the setting of high clinical suspicion plus one of the following: 1) fever after contact with rodents in the endemic areas. 2) unexplained adenitis with fever and hypotension. 3) gram-negative bacilli in a patient with pneumonia and bloody expectoration. Additionally, any gram-negative bacilli found in the lymph node sample should lead to diagnosis as few gram-negative bacteria cause adenitis.[7] Classically, an aspirate from the bubo, is obtained, stained, and cultured to demonstrate the bacterium. Y. pestis is a gram-negative bacillus and grows well on most culture media.[8] Complete blood counts may demonstrate significant leukocytosis over 20000 per mm^3 combined with thrombocytopenia.[2] Neutrophils of affected patients may demonstrate Dohle bodies, although the sensitivity and specificity of this finding are not well-established.[9] In areas of high disease prevalence, such as Madagascar, rapid testing utilizing the F1 antigen is common.[7] Tests with varying sensitivities and specificities exist, including immunofluorescence, PCR, and ELISA, among others. The specific test chosen depends on the resources available and the prevalence of the disease in the practice setting.[4][10] In the United States, confirmation is possible by sending cultures to the CDC.[10]

Treatment / Management

Early antibiotics are the cornerstone of effective treatment for the plague due to the rapid progression of each disease subtype. Given these potentially poor clinical outcomes, treatment should begin based on clinical suspicion, as described above. Aminoglycosides are considered first-line treatment, with gentamicin currently replacing the classic first-line agent, streptomycin, as the preferred agent in some areas. Alternatives include doxycycline and tetracycline, though treatment with these is recommended to be extended from the typical 7 to 10 days to 14 days due to the bacteriostatic nature of tetracyclines. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole has been used, but with decreased efficacy compared to first-line agents. Chloramphenicol is the preferred treatment for plague meningitis.[8][4] The US Food and Drug Administration recently approved levofloxacin for use in patients with plague based on animal and in vitro studies.[11] With concerns for widespread dissemination of plague via bioterrorism, vaccines to prevent Y. pestis infection exist, though none of these is in extensive use due to questions surrounding efficacy.[1] Currently, as many as 17 vaccines are in production.[12]

Differential Diagnosis

As previously discussed, high clinical suspicion is essential for the diagnosis of plague, as the differential diagnosis for each of its presentations is quite broad. For bubonic plague, any presentation involving lymphadenopathy in an ill-appearing patient is within the differential; this includes a variety of bacterial, viral, fungal, oncologic, medication-related, autoimmune, and inflammatory causes of lymphadenopathy or lymphadenitis.[13][14] However, bubonic plague is unique in its presentation regarding the suddenness in the onset of fever and buboes, including the rapid progression of intense inflammation of the buboes and fulminant deterioration of the patient clinically.[8] Similarly, the differential diagnosis for hemoptysis and fever ranges widely to include viral bronchitis, any subtype of pneumonia (particularly tuberculosis), pulmonary embolism, inflammatory, and oncologic causes.[15] However, the suddenness of onset, and severity of the disease, as well as the presence of buboes, strongly suggests plague over other etiologies.[8] Perhaps more so than any other presentation of plague, septicemic plague’s presentation of fever and hypotension is broad and encompasses all infectious and inflammatory causes of sepsis, as well as any cause of shock.[16] Clinical suspicion, followed by diagnostic testing, is of utmost importance in these cases.[2] There have been documented cases of travel-associated plague in the United States. Thus, clinical suspicion should remain high in endemic areas, as well as in patients who have a history of recent travel to endemic areas.[11]

Prognosis

The prognosis of all presentations of plague is poor. Bubonic plague has an estimated mortality of 50 to 90% untreated. Septicemic plague may have lower mortality, at approximately 22%. Proper diagnosis and early treatment of both of these etiologies decrease the mortality to 5 to 15%.[4] As noted above, current mortality among known cases is approximately 7%.[1] Pneumonic plague is considered invariably fatal unless treated immediately following the exposure or within the first day of illness.[8] Even with proper treatment, mortality is greater than 50%.[4]

Complications

Many potential complications of plague exist, ranging from death to various alternative presentations from the classic bubonic plague. Significant complications include pharyngitis, secondary pneumonic plague, bacteremia, and septic shock. Also, meningitis is a known complication and typically occurs at least one week following untreated bubonic plague leading to increased mortality.[8][4]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Even in plague endemic regions in Uganda, the unpredictable pattern of disease and outbreaks lead to challenges in both public health and patient recognition of disease.[17] Plague is even rarer in the US, and knowledge regarding the risk factors for contraction and symptoms of the disease is not widespread. Avoiding dead rodents is the most critical step to avoid infection.[2] If living in an endemic area, deterrence involves avoiding fleas and rodents by living in ratproof houses, utilizing shoes and clothing that cover the legs, and applying insecticides to the household as needed. Sick cats should be avoided and dead animals should not be handled without gloves.[8] If a person does have a concern for exposure, he or she should seek care for fever, swollen lymph nodes, cough with or without hemoptysis, headache with a stiff neck, or sore throat. Early treatment is an essential factor in decreasing the risk of death and further complications.[4]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Plague is challenging to recognize and treat, given its rare presentation in many practice settings. Patients may present classically, with high fever, hypotension, and buboes. Alternatively, they may present vaguely with sepsis or pneumonic plague. Diagnosis and early treatment are key to diagnosis. Therefore, the entire interprofessional team is important to patient outcomes.

Given the pathogenicity of Y. pestis, patients with plague are likely to be ill-appearing on presentation and may present to any healthcare access point. The healthcare team should attempt to recognize the characteristic clinical signs and elicit the travel history and/or exposure to help make the clinical diagnosis and begin treatment. Consideration for infectious disease specialist consultation would likely be beneficial, especially when the diagnosis is uncertain. Further, given the severity of illness, specialists in intensive care may need to be involved.

Further, the entire interprofessional healthcare team should be aware of the suspected diagnosis and the potential for spread to both caregivers and other patients alike. An infectious disease specialist must be brought on the case and can consult with a board-certified infectious disease pharmacist to begin empiric treatment, and plot the therapy course pending validation. Nursing staff will administer medical treatment and monitor the patient's signs and symptoms, reporting to the clinical staff any concerns or changes. All team members with patient contact must engage in prophylactic measures. Recommendations for the care of people with plague include:

- Droplet precautions for 48 hours following the initiation of antibiotics.

- Wear surgical masks in rooms to avoid transmission of large droplets.

- Isolation precautions.

- Monitor for fever in exposed individuals

- Consider post-exposure prophylaxis (with doxycycline, a fluoroquinolone, or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole) for close contacts who were unprotected by the above (close defined as coming within 2 meters of the patient).

- Isolation of asymptomatic individuals without symptoms is not recommended.[8] [Level V]

Plaque is a reportable disorder, and the appropriate authorities must receive notification within 24 hours. The infection is highly lethal, and teamwork is vital for the prevention of spread. Because of the lethal nature of the infection, only selected healthcare workers should be involved in patient care. All staff should use strict universal and isolation precautions when managing patients with plague. An interprofessional team approach to care of plague victims will result in the best outcomes. [Level 5]

(Click Image to Enlarge)

This plague patient is displaying a swollen, ruptured inguinal lymph node, or buboe. After the incubation period of 2-6 days, symptoms of the plague appear including severe malaise, headache, shaking chills, fever, and pain and swelling, or adenopathy, in the affected regional lymph nodes, also known as buboes.

Contributed by The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)