Community-Acquired Pneumonia

- Article Author:

- Hariharan Regunath

- Article Editor:

- Yuji Oba

- Updated:

- 8/10/2020 9:09:17 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Community-Acquired Pneumonia CME

- PubMed Link:

- Community-Acquired Pneumonia

Introduction

Community-acquired pneumonia is a leading cause of hospitalization, mortality, and incurs significant health care costs. As disease presentation varies from a mild illness that can be managed as an outpatient to a severe illness requiring treatment in the intensive care unit (ICU), determining the appropriate level of care is important for improving outcomes in addition to early diagnosis and appropriate and timely treatment.[1][2][3][4]

Etiology

The pathogens causing community-acquired pneumonia can be classified as two types: (1) Typical agents such as Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, Staphylococcus aureus, Group A Streptococci, anaerobes, and gram-negative organisms and (2) Atypical agents such as Legionella, Mycoplasma, Chlamydia pneumoniae, and C. psittaci. Influenza and non-influenza respiratory viruses have been increasingly detected as pathogens depending on the availability of polymerase chain reaction-based detection methods. Worldwide, S. pneumoniae and H. influenzae are the leading causes of bacterial pneumonia. The most common pathogens identified in the most recent population-based active surveillance in the United States were human rhinovirus, influenza virus, and Streptococcus pneumoniae.

Epidemiology

The estimated worldwide incidence of community-acquired pneumonia varies between 1.5 to 14 cases per 1000 person-years, and this is affected by geography, season, and population characteristics. In the United States, the annual incidence is 24.8 cases per 10,000 adults with higher rates as age increases. Pneumonia is the eighth leading cause of death and first among infectious causes of death. The mortality rate is as high as 23% for patients admitted to the intensive care unit. All patients with comorbid illness are considered at risk for pneumonia, but specific risk factors exist for specific pathogens including (1) drug-resistant pneumococci - age greater than 65, exposure to children in daycare centers, intake of beta-lactam in previous 90 days, alcohol use disorder, chronic medical conditions, immune-suppression; and (2) pseudomonas - bronchiectasis, malnutrition, corticosteroid therapy, antibiotic intake for greater than seven days in the preceding month. Other etiological clues from epidemiology include the following: coccidioidomycosis in the Southwestern United States, blastomycosis or histoplasmosis in the states of the Ohio River valley, bird exposures for Chlamydia psittaci, contact with flea-infested or infected rodent or rabbits during outside activities such as lawn mowing in the Northeast U.S. (Martha's Vineyard, Cape Cod, etc.) for tularemia pneumonia.

Pathophysiology

Colonization of the pharynx with pathogens, followed by micro-aspiration, is the mechanism of entry into the lower respiratory tract. In the interaction between the pathogen and host pulmonary defense, pneumonia results if there is a defect in host defense or it is overcome by high inoculum or virulence of the pathogen. Hematogenous spread and macro-aspiration are other mechanisms.

History and Physical

Fever, chills, cough productive of purulent sputum, dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, and weight loss are common symptoms. The elderly, patients with alcohol use disorder, and those who are immune-compromised can have less evident or systemic symptoms such as weakness, lethargy, altered mental status, dyspepsia, or other upper gastrointestinal symptoms, and absence of fever. Some manifestations provide etiological clues such as diarrhea, headache, and confusion (related to hyponatremia) for Legionella; and otitis media, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, or anemia/jaundice (hemolytic anemia) for Mycoplasma. Pneumonia can result in acute decompensation of underlying chronic illness like congestive heart failure, which can confound the initial presentation and result in diagnosis and treatment delays.

Evaluation

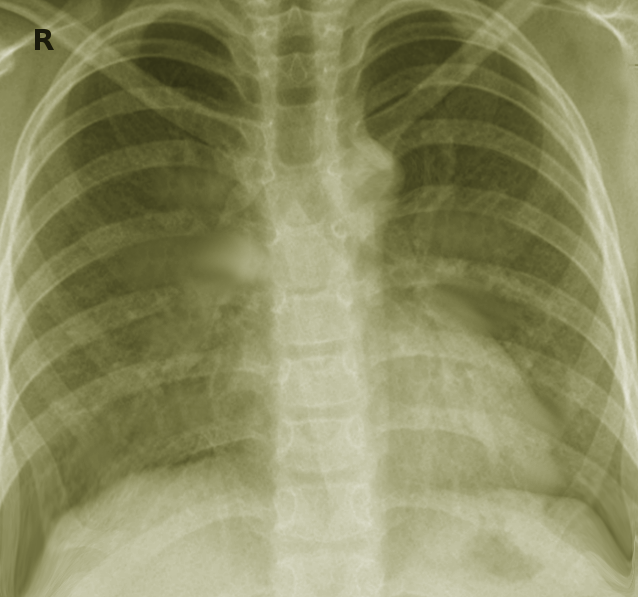

A complete blood count with differentials, serum electrolytes, and renal and liver function tests are indicated for confirming evidence of inflammation and assessing severity. A chest x-ray will be needed to identify an infiltrate or effusion, which, if present, will improve diagnostic accuracy. In hospitalized patients, blood and sputum cultures should be collected, preferably before the institution of antimicrobial therapy, but without delay in treatment. Urine for Legionella and pneumococcal antigens must be considered as they aid in diagnosis when cultures are negative. In the presence of confounding comorbidities, such as congestive heart failure, serum procalcitonin levels can be used as a biomarker to initiate and guide antimicrobial therapy. Influenza testing is recommended during the winter season. If available, testing for respiratory viruses on nasopharyngeal swabs by molecular methods can be considered. CURB 65 (confusion, urea greater than or equal to 20 mg/dL, respiratory rate greater than or equal to 30/min, blood pressure systolic less than 90 mmHg or diastolic less than 60 mmHg), and Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) are tools for severity assessment to determine the treatment setting, such as outpatient versus inpatient, but accuracy is limited when used alone or in the absence of effective clinical judgment. Serology for tularemia, endemic mycoses, or C. psittaci can be sent in the presence of epidemiologic clues.[5][6][7]

Treatment / Management

For outpatients, monotherapy with a macrolide (erythromycin, azithromycin, or clarithromycin) or doxycycline is recommended. In the presence of comorbid illness (chronic heart disease excluding hypertension; chronic lung disease - COPD and asthma; chronic liver disease; chronic alcohol use disorder; diabetes mellitus; smoking; splenectomy; HIV or other immunosuppression) a respiratory fluoroquinolone (high-dose levofloxacin, moxifloxacin, gemifloxacin) or a combination of oral beta-lactam (high dose amoxicillin or amoxicillin-clavulanate, cefuroxime, cefpodoxime) and macrolide is recommended.[7][8][9][10]

For patients with a CURB 65 score of greater than or equal to 2, inpatient management is recommended. A respiratory fluoroquinolone monotherapy or combination therapy with beta-lactam (cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, ampicillin-sulbactam, or ertapenem) and macrolide are recommended options for nonintensive care settings.

Admission to the intensive care unit must be considered in patients with three or more signs of early deterioration. These include respiratory rate greater than 30, PaO2/FiO2 less than or equal to 250, multilobar infiltrates, encephalopathy, thrombocytopenia, hypothermia, leucopenia, and hypotension. Combination therapy with a beta-lactam and either a macrolide or a respiratory fluoroquinolone is recommended. In patients with possible aspiration, ampicillin-sulbactam, or ertapenem can be used. Monotherapy is not recommended.

If risk factors for pseudomonas are present, then anti-pseudomonal beta-lactam (piperacillin-tazobactam, cefepime, ceftazidime, meropenem, imipenem) along with either an anti-pseudomonal fluoroquinolone (ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin) or a combination of aminoglycoside and azithromycin are recommended. Vancomycin or linezolid should be added if community-acquired methicillin-resistant S. aureus is a consideration.

The recommended duration of therapy is 5 to 7 days in patients with a favorable clinical response such as the absence of fever for more than 48 to 72 hours, not requiring supplemental oxygen, and resolution of tachycardia, tachypnea, or hypotension. Prolongation of therapy is indicated in patients with a delayed response, certain bacterial pathogens such as Pseudomonas (14 to 21 days) or S. aureus (7 to 21 days), or Legionella pneumonia (14 days), and for complications such as empyema, lung abscess, or necrotizing pneumonia. Chest tube placement will be needed to drain an empyema, and in cases with multiple loculations, a surgical decortication may be needed. A 14-day therapy with macrolide or doxycycline will treat tularemia pneumonia or psittacosis, and itraconazole is the drug of choice for pneumonia caused by coccidioidomycosis or histoplasmosis.

A five-day therapy with oseltamivir is recommended for all patients who test positive for the influenza virus. For outpatients with delayed presentation (greater than 48 hours from onset of symptoms), there is no benefit. Still, any hospitalized patients with influenza must be treated with this agent irrespective of the time of presentation from the onset of illness.

Intravenous glucocorticoids can be considered in critically ill patients with community-acquired pneumonia without risk factors for adverse outcomes from the use of steroids (e.g., influenza infection).

Differential Diagnosis

- Acute bronchitis

- Acute exacerbation of chronic bronchitis

- Aspiration pneumonitis

- Congestive heart failure and pulmonary edema

- Pulmonary fibrosis

- Myocardial infarction

- Systemic lupus erythematosus pneumonitis

- Pulmonary drug hypersensitivity reactions (nitrofurantoin, daptomycin)

- Drug-induced pulmonary disease (bleomycin)

- Sarcoidosis

- Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia

- Pulmonary embolus

- Pulmonary infarction

- Bronchogenic carcinomas

- Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener granulomatosis)

- Lymphoma

- Tracheobronchitis

- Radiation pneumonitis

Pearls and Other Issues

All adults 65 years and older and those considered at risk for pneumonia must receive the pneumococcal vaccination. There are two vaccines available: PPSV 23 and PCV 13.

Current ACIP recommendations for unvaccinated non-immune-compromised individuals aged 19 to 64 years old and at risk for pneumonia, first should receive PPSV 23. After age 65, a dose of PCV 13 can be given (after at least one year of the first dose of PPSV 23), followed by the second dose of PPSV 23 spaced at least one year from PCV 13 and 5 years from the first dose of PPSV 23. For patients who are immune-compromised or asplenic (functional or anatomical) and 19 to 64 years old, first give PCV 13, followed by the first dose of PPSV 23 8 weeks or later and second dose PPSV 23 after five years. A booster PPSV 23 can be given for a patient 65 years or older after at least five years or longer from the second dose of PPSV 23.

For all unvaccinated adults 65 years or older, first vaccinate with PCV 13, followed by PPSV 23 at least a year later for immune-competent patients and at least eight weeks or more apart for patients who are immune-compromised or asplenic.

Influenza vaccination is recommended for all adult patients at risk for complications from influenza. Inactivated flu shots (trivalent or quadrivalent, egg-based or recombinant) are usually recommended for adults. Live attenuated intranasal vaccine can be given to healthy, nonpregnant adults who are less than 49 years old. It is contraindicated in pregnancy, the immune-suppressed or health care workers caring for them, and in those with comorbidities.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Patients with community pneumonia may present to the primary care provider or the emergency department. Hence these professionals should be aware of the signs and symptoms. The health care team can improve outcomes. The team can include primary care, emergency department personnel, specialists, nurses, and pharmacists. If the diagnosis is not clear cut, then an infectious disease or pulmonology consult is recommended. Most patients do respond to outpatient antibiotic therapy for 5-7 days. Patients who are short of breath, febrile, and in respiratory distress need to be admitted. Some patients may present with a parapneumonic effusion, which may require drainage. Nurses monitor the patients and report current status and updates to the rest of the team. Pharmacists evaluate medication choice, check for allergies and interactions, and educate patients about side effects and the importance of compliance. The providers should encourage all patients to get the annual influenza vaccine. In addition, all adults 65 years and older and those considered at risk for pneumonia must receive the pneumococcal vaccination. The outcomes in most patients with community-acquired pneumonia are excellent. [11] [Level 5]

(Click Image to Enlarge)

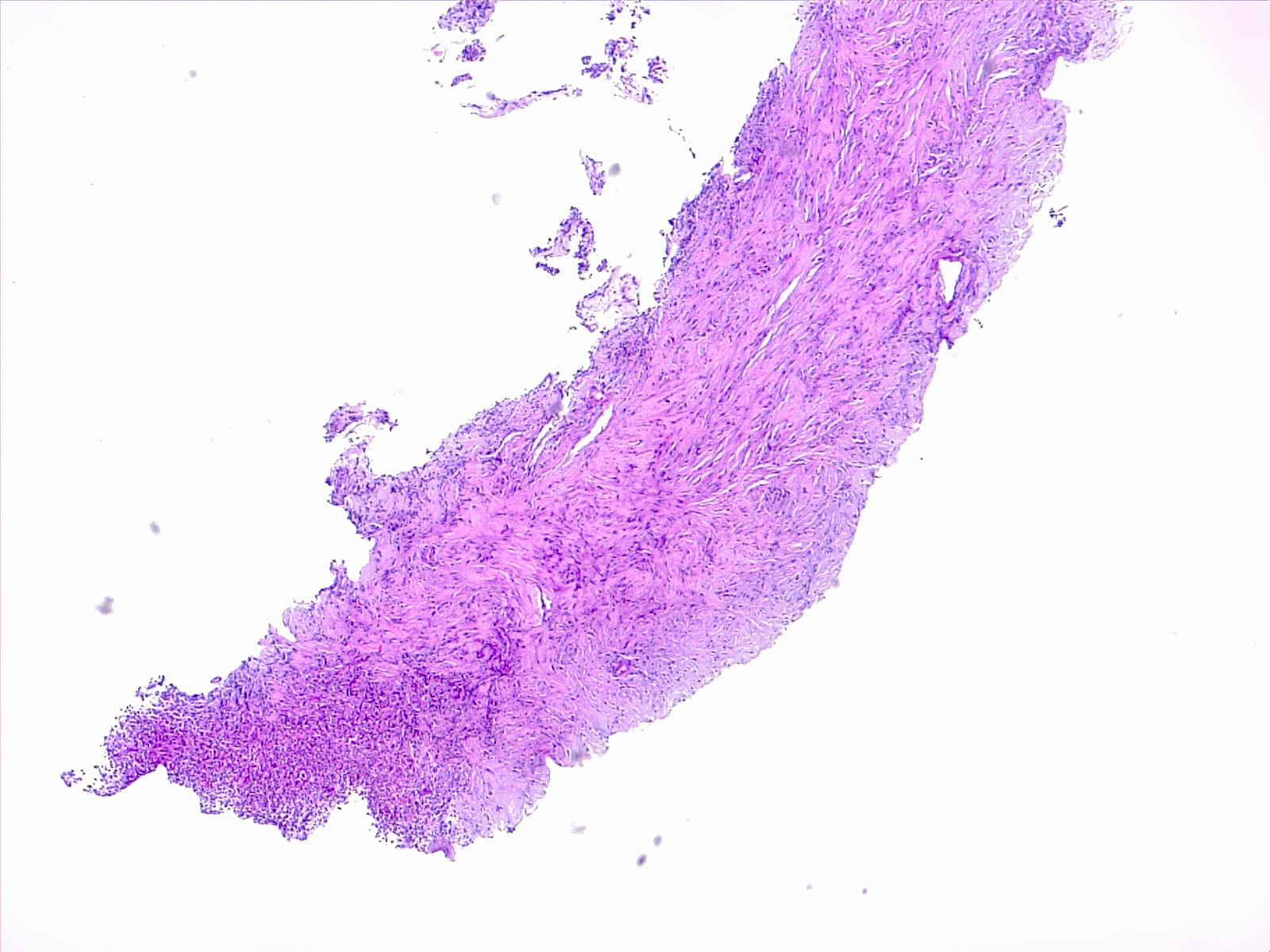

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)