Posterior Polymorphous Corneal Dystrophy

- Article Author:

- Christian Guier

- Article Author:

- Bhupendra Patel

- Article Author:

- Thomas Stokkermans

- Article Editor:

- Arun Gulani

- Updated:

- 8/11/2020 11:36:24 AM

- For CME on this topic:

- Posterior Polymorphous Corneal Dystrophy CME

- PubMed Link:

- Posterior Polymorphous Corneal Dystrophy

Introduction

Corneal dystrophies (CD) are a group of genetically determined diseases that are restricted to one or more layers of the cornea. These can be characterized as bilateral, symmetric, slowly progressive and have no systemic manifestations. Most often these are inherited as a dominant trait. Recessive inheritance occurs seldomly in a limited number of pedigrees. Ocular symptoms of CD can include blurred vision, foreign body sensation, eye pain, photophobia, and lacrimation [1].

Posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy (PPCD) was described first by Koeppe in 1916. PPCD is a rare, hereditary condition passed on in an autosomal dominant manner. Manifestations of this condition are highly variable. Affected family members may have distinctly different ocular presentation. The Descemet basement membrane laid down by endothelial cells is abnormally thickened in PPCD. Corneal edema associated with PPCM may be evident at a very young age. However, the majority of patients are asymptomatic and diagnosis occurs years later at the time of a routine ocular health examination [2].

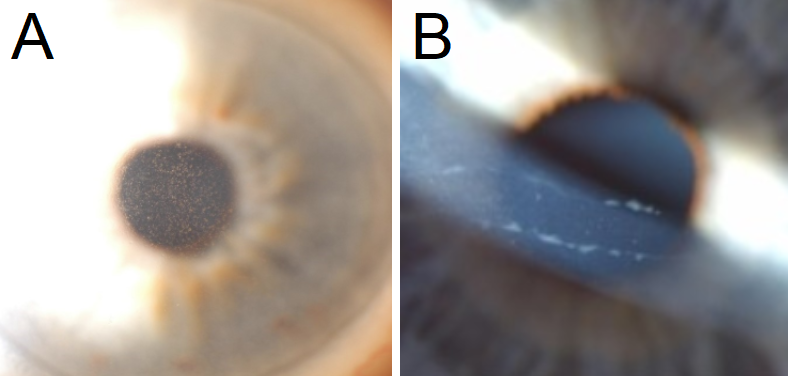

Bilateral presentation is typical for corneal dystrophies but an asymmetric appearance is not uncommon with PPCD. Corneal findings are either nonprogressive or very slowly progressive [3]. This condition is most easily identified with careful inspection of the posterior cornea, specifically the Descemet membrane and the adjacent corneal endothelium. In PPCD, the Descemet basement membrane laid down by endothelial cells is abnormally thickened. Groupings of blister-like vesicles and gray-white plaques lead to opacification of the posterior cornea. The appearance of the opacities at the Descemet membrane may be characterized by one of three different distribution patterns; vesicular, band-like or diffuse. These polymorphous lesions may be visualized at the slit lamp biomicroscope with moderate to high magnification using direct or, preferentially, retro-illumination techniques. Vesicular lesions are frequently clustered together. They have a cystic appearance, variably sized. The well-circumscribed lesions have a translucent center that is banded by a darker perimeter. The band-like lesions are most often seen as two parallel bands with serrated edges. These bands can be seen in any orientation but most often they are oriented horizontally. The band length can vary from 2 to 10mm. In contrast to the Descemet's findings associated with trauma or congenital glaucoma (Haab striae), in PPCD the bands do not taper at the ends [4]. Diffuse polymorphous opacities are the least common finding but tend to be the most visually disruptive. Geographic aggregations of small opacities are dispersed across a portion of the Descemet membrane creating a hazy appearance of the posterior stroma. A peau d'orange appearance is appreciated with retro-illumination [5].

PPCD may also involve the iris and the anatomical angle. Rather than confining themselves to the posterior surface of the cornea, the aberrant endothelial cells can migrate erratically across the chamber angle and onto the peripheral iris surface. Abnormal basement membrane is secreted, creating iridocorneal adhesions and a glass-like appearance that can be appreciated gonioscopically. On the iris surface, this membrane can lead to corectopia and pupillary ectropion. Areas of peripheral anterior synechiae (PAS) with segmental zones of angle-closure can occur, increasing the risk for glaucoma [6]. Additionally, peripheral corneal edema may be seen overlaying any broad regions of iridocorneal adhesion [7].

Etiology

Posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy (PPCD) is genetically heterogeneous with variable expression.

Several genetic mutations are implicated in the genesis of PPCD 1-4.

- PPCD1 (122000) is due to a heterozygous mutation in the promoter of the OVOL2 gene (616441), cytogenic location 20p11.22.

- PPCD2 (609140) is due to a mutation in the COL8A2 gene (120252), cytogenic location 1p34.2-p32.3.

- PPCD3 (609141) is due to a mutation in the ZEB1 gene (189909), cytogenic location 10p11.22.

- PPCD4 (618031) is due to a mutation in the GRHL2 gene (608576), cytogenic location 8q22.

Epidemiology

Posterior polymorphous dystrophy (PPCD) is considered very rare.

As many patients are asymptomatic the exact incidence of PPCD is unknown. PPCD affects males and females equally.

Reports estimate higher than normal prevalence in the Czech Republic (estimated 1:100,000) [8].

Pathophysiology

The symptoms in this condition range remarkably from asymptomatic to aggressive, vision-threatening. Posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy (PPCD) can be evident at birth but is most often detected later in life. Abnormal developmental differentiation of endothelial cells leads to secondary alterations of the Descemet membrane. This results in multiple laters of epithelium-like cells within the corneal epithelium. These aberrant cells migrate secreting atypical basement membrane resulting in thickening of the Descemet membrane. Groupings of polymorphic irregularities are evident at the Descemet membrane. These are associated with varying levels of corneal opacification and endothelial degradation. In mild disease with sparse tissue irregularities limited only to the posterior cornea patients may report blurred vision, glare symptoms and, infrequently, eye pain.

Compromises at the Descemet membrane in PPCD are associated with topographic changes in the cornea. Corneal steepening may manifest as regular astigmatism, irregular astigmatism or keratoconus. In patients with intact neurodevelopment of the visual system, visual function can be improved with glasses, standard or specialty contact lenses or certain refractive procedures. However, infants and toddlers have incomplete development of their abilities to process visual stimuli. Any significant asymmetry in refractive status during the critical or sensitive period, up to age 3 and age 9 respectively, may delay or limit the maturation of visual sensory development in one or both eyes [9]. In PPCD the manifestations of the dystrophy can be asymmetric. Similarly, the refractive disparity can occur, which if left untreated can result in anisometropic amblyopia [10], [11].

In severe cases of PPCD, the risk for permanent loss of vision is increased. Endothelial compromise affects corneal deturgescence. Significant endothelial compromise can lead to focal or diffuse corneal edema. As fluid accumulates in the corneal stroma, swelling and opacification occur. Corneal bullae may form migrating anteriorly resulting in sharp eye pains. Vision may be profoundly limited by dense central corneal edema. Further corneal decompensation will occur. Surgical intervention is necessary to restore endothelial function and regain some level of corneal clarity [12]. As is the case with refractive disparity induced by high astigmatism, there is potential for infants and toddlers to develop amblyopia [13]. Deprivation amblyopia occurs in the setting of visual obscuration by congenital or traumatic cataract, eyelid ptosis or media opacity such as corneal opacification.

With PPCD the abnormal cells have several epithelium-like characteristics. The aberrant corneal endothelium is multilayered with keratin, numerous microvilli, and desmosomes. The thickened tissue has greater biomechanical resistance to an outside force. This can alter corneal hysteresis leading to an over-estimation of measured intraocular pressures which confounds the diagnosis of glaucoma.

Irregular basement membrane secretions bridging the anatomical angle can lead to elevated intraocular pressure and secondary glaucoma [14]. Peripheral anterior synechia or iridocorneal adhesions may be evident with gonioscopy. In advanced cases, iris atrophy and corectopia may present.

Penetrating keratoplasty is required for 20-25% of patients with significant endothelial involvement and diffuse corneal edema [15], [16]. If the corneal stroma and epithelium are not edematous lamellar keratoplasty is preferred as this technique yields faster healing and improved visual outcomes [15]. Glaucoma filtering surgery may be necessary for a disease that is recalcitrant to topical therapy [17]. In each instance, the prognosis is guarded as irregular endothelial cells persist disrupting the grafted tissues or the drainage apparatus.

Histopathology

A healthy endothelium is arranged at the posterior cornea in a single layer with a predictable hexagonal cellular configuration. In posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy (PPCD) the endothelial cells undergo an aberrant differentiation. There is a proliferation of metaplastic cells resulting in multiple layers of cells that manifest epithelium-like characteristics forming an anomalous collagenous layer. Scanning electron microscopy of corneal tissue demonstrates a transformation of the posterior corneal surface with degenerated endothelial cells, fibroblast-like cells, and stratified epithelial-like cells with numerous microvilli, keratin, and desmosomes. Like epithelium, these cells migrate across the Descemet membrane and, on occasion, across the trabecular meshwork and anterior iris surface. The thickened tissue has greater biomechanical resistance to outside force affecting corneal hysteresis [18][19].

History and Physical

Posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy (PPCD) frequently is an asymptomatic condition that may be diagnosed at the time of a routine eye examination.

- PPCD is a hereditary disease. A family history of corneal disease should be elucidated.

- Asymptomatic patients will have normal or near-normal visual acuity.

- Glare symptoms are frequently reported.

- With careful biomicroscopy, bilateral polymorphic irregularities are evident at the Descemet membrane and the endothelium.

- Although corneal dystrophies are a bilateral entity it is not uncommon to have asymmetric signs.

- The appearance of the lesions is highly variable. Clusters of blister-like vesicles are most commonly encountered.

- Another pathognomonic configuration has parallel linear bands with scalloped edges across or adjacent to the visual axis.

- Larger areas of diffuse opacities are rare but are more likely to diminish visual function.

- The onset of signs or symptoms should be ascertained. Infants or toddlers within the critical or sensitive period are likely to develop amblyopia.

- Structural irregularities of the Descemet membrane can induce corneal steepening and high astigmatism [20].

- Significant asymmetry in refraction may contribute to the development of anisometropic amblyopia in susceptible children.

- Rarely corneal edema due to compromised corneal endothelium is evident at birth.

- Persistent central corneal opacity may contribute to the development of deprivation amblyopia in susceptible children.

- If endothelial findings are present gonioscopy should be performed to evaluate the anatomic angle.

- Peripheral anterior synechia (PAS) can found in isolation or as broad bands. Peripheral corneal edema may overly broad bands of PAS.

- If intraocular pressure is elevated a careful glaucoma workup should be initiated.

- If there are iris or pupillary distortions a glaucoma workup should be initiated.

Evaluation

Careful evaluation of the posterior corneal tissues with slit-lamp biomicroscope allows immediate, in-office visualization of the polymorphous lesions.

- Polymorphous lesions may be visualized at the biomicroscope with moderate to high magnification using direct or, preferentially, retro-illumination techniques.

- Specular microscopy enables high-resolution imaging of the characteristic findings associated with PPCD within Descemet membrane and endothelial layer.

- Endothelial cell count can be diminished. The remaining endothelium demonstrates structural pleomorphic irregularities.

- Confocal microscopy is of value in definitively identifying features characteristic of PPCD.

- Careful intraocular pressure measurement is necessary to screen for glaucoma.

- Anterior segment optical coherence tomography (OCT) images any abnormalities associated with aberrant endothelium bridging the anatomic angle.

- As an autosomal dominant entity, examination of family members may be helpful in confirming the diagnosis.

Treatment / Management

Asymptomatic patients with limited findings should be educated regarding the presence and potential significance of posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy (PPCD).

- Initiate amblyopia therapy in young children with high or asymmetric refractive error.

- Initiate immediate referral to a pediatric ophthalmologist if non-clearing corneal edema is present.

- Initiate amblyopia therapy in young children that have a history of corneal edema affecting form perception.

- Long-term monitoring of the posterior corneal layers is required.

- If secondary epithelial erosions or bullous keratopathy are present a bandage soft contact lens should be considered.

- If endothelial findings are present, gonioscopy should be performed to evaluate the anatomic angle.

- If intraocular pressure is elevated, a careful glaucoma workup should be initiated.

- If findings substantiate a diagnosis of glaucoma, then initiate first-line topical glaucoma therapy.

- Monotherapy with a prostaglandin analog will control intraocular pressure (IOP) in the majority of cases.

- Changing class or adding a medication may be necessary to realize IOP control.

- Laser peripheral iridotomy (LPI) is not recommended if epithelialization of the trabecular meshwork has been identified.

- If unable to achieve or maintain rigid IOP control, glaucoma filtering surgery may be necessary.

- Minimally invasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS) offers promise.

- If there are iris or pupillary distortions a glaucoma workup should be initiated.

- Penetrating Keratoplasty (PK) has historically been successful, but has slow and challenging recovery as well as variable visual outcomes.

- Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK) if the corneal stroma and epithelium are unaffected.

- Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty (DSAEK) is preferred if the corneal stroma and epithelium are unaffected.

- If iridocorneal adhesions are present corneal grafting procedures are at risk for failure.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses includes:

- ICE syndrome (Chandler syndrome).

- Congenital hereditary endothelial dystrophy.

- Pre-Descemet corneal dystrophy.

- Fuchs endothelial dystrophy.

- Primary congenital glaucoma.

- Traumatic rupture of Descemet membrane.

Prognosis

The prognosis for posterior polymorphous dystrophy (PPCD) is dependent on the extent of the disease.

- In most cases, PPCD is a static or very slowly progressive disease.

- The frequency of follow-up required is dependant on the severity of the disease.

- Patients with mild disease that are identified in adulthood have a good prognosis and are not likely to require treatment.

- If significant refractive disparity is present in childhood anisometropic amblyopia may develop.

- Infants with corneal edema require timely intervention to reduce the potential for developing deprivation amblyopia.

- Those with iridocorneal adhesions should be monitored for glaucoma.

- Those with elevated intraocular pressure, visual field defects or glaucomatous optic nerve appearance should be treated for glaucoma.

- Penetrating keratoplasty should be considered if corneal opacities limit visual potential.

- If iridocorneal adhesions are present corneal grafting procedures are at risk for failure.

Complications

Infants and toddlers are at risk for amblyopia if neurodevelopment of the visual system is disrupted.

- Intervention is imperative during the critical period (up to age 3). Strongly recommended during the sensitive period (ages 3 to 9).

- To reduce the risk of complications, patients prescribed bandage soft contact lens (BSCL) therapy must be proficient in the handling and care of the BSCL.

- Patients prescribed BSCL are at risk for infection, pain and vision loss if secondary corneal infection were to occur.

- Those with iridocorneal adhesions should be monitored for glaucoma.

- Those with elevated intraocular pressure, visual field defects or glaucomatous optic nerve appearance should be treated for glaucoma.

- Penetrating keratoplasty should be considered if corneal opacities limit visual potential.

- If iridocorneal adhesions are present corneal grafting procedures are at risk for failure.

- Posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy can recur in corneal grafts.

Consultations

- Referral to a pediatric ophthalmologist if non-clearing corneal edema is present in an infant or toddler.

- Referral to strabismologist if strabismus is present in an infant or toddler.

- Referral to a corneal specialist if posterior corneal opacification necessitates corneal transplantation.

- Referral to a corneal specialist if corneal edema or bullous keratopathy necessitates corneal transplantation.

- Referral to a glaucoma specialist if poor intraocular pressure control necessitates glaucoma filtering surgery.

- Referral to a glaucoma specialist if glaucomatous progression necessitates glaucoma filtering surgery.

Deterrence and Patient Education

- Asymptomatic patients with limited findings should be educated regarding the presence and potential significance of posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy (PPCD).

- Early vision screening is essential.

- Amblyopia therapy is required for young children with high or asymmetric refractive error.

- Periodic ophthalmic evaluation is necessary to screen for anterior segment irregularities.

- Initiate immediate referral to a pediatric ophthalmologist if non-clearing corneal edema is present.

- Amblyopia therapy is recommended for young children with corneal edema affecting form perception.

- If endothelial findings are present, gonioscopy should be performed to evaluate the anatomic angle.

- If intraocular pressure is elevated, a careful glaucoma workup should be initiated.

- If there are iris or pupillary distortions a glaucoma workup should be initiated.

- If findings substantiate a diagnosis of glaucoma, glaucoma therapy is imperative.

- Options include topical, laser, surgical and minimally invasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS).

-

- Laser peripheral iridotomy (LPI) is not recommended if epithelialization of the trabecular meshwork has been identified.

- If unable to achieve or maintain rigid IOP control, glaucoma filtering surgery may be necessary.

- Minimally invasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS) offers promise.

- Penetrating Keratoplasty (PK) has historically been successful, but has slow and challenging recovery as well as variable visual outcomes.

- Lamellar corneal transplantation offers faster recovery and improved visual outcomes.

- Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK) if the corneal stroma and epithelium are unaffected.

- Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty (DSAEK) is preferred if the corneal stroma and epithelium are unaffected.

- If iridocorneal adhesions are present corneal grafting procedures are at risk for failure.

Pearls and Other Issues

- Most cases of posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy (PPCD) do not require any treatment.

- In infancy, this condition is easily confused with buphthalmos or congenital hereditary endothelial dystrophy (CHED).

- Secondary opinion should be sought if the diagnosis is ambiguous.

- The thickened corneal tissue has greater biomechanical resistance to outside force affecting corneal hysteresis.

- Intraocular pressure measurements may be overestimated lending to the appearance of ocular hypertension.

- Asymmetric findings involving the cornea, trabecular meshwork and iris must be differentiated from Chandler syndrome.

- Laser procedures for glaucoma may not be effective if the trabecular meshwork is altered by irregular or aberrant endothelial tissues.

- Goniotomy procedures for glaucoma may not be effective if the trabecular meshwork is altered by irregular or aberrant endothelial tissues.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Although onset is at birth or very shortly afterward, many patients with posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy (PPCD) are visually asymptomatic and the condition is not diagnosed for years to decades later. If lesions at Descemet membrane are consistent with PPCD but there is no evidence of corneal edema, elevated intraocular pressure or irregularities of the angle or iris, then it is appropriate to recommend periodic comprehensive ophthalmic evaluation by a primary eyecare practitioner.

If glaucoma is diagnosed and topical therapy is prescribed the ophthalmic care provider team must educate regarding the importance of rigid compliance using medications as well as the proper use and storage of topical medications. This can be performed by the physician, nurse, ophthalmic assistant or pharmacy staff.

If intraocular pressure is not adequately controlled or there is evidence of glaucomatous progression, then it is appropriate to seek glaucoma specialist evaluation to determine suitability for altered topical therapy, new laser therapy or glaucoma filtration surgery.

If corneal edema is present and responsive to topical hyperosmotic agents it is appropriate to provide education regarding the proper use of topical medications. This can be performed by the physician, nurse, ophthalmic assistant or pharmacy staff. Similarly, the proper placement, removal, and care for bandage contact lenses should be trained by a qualified physician, nurse or ophthalmic assistant.

If recalcitrant corneal edema obscures vision or leads to painful bullae or corneal erosions, then a corneal specialist should evaluate the suitability for a form of keratoplasty.

Patients must be aware that they too have the right and responsibility to communicate any perceived changes or difficulties to their healthcare team.